N Acetyl Cysteine in Problem Drug Use and Psychiatric Treatments: A Verbatim Science Method

This article explores n acetyl cysteine as a therapeutic and continues the exploration of scientific method and research techniques available to us all which help us establish whether knowledge is increasingly reliable or decreasingly reliable. The professionalisation and financialisation of various aspects of life brings with it pros and cons. As science and medicine become increasingly politicised, it seems a vital part of culture to ensure the demystification of these fields so that everyone can gain from the agency to make up their own mind on issues which are relevant to them.

I am exploring the various tools and instruments we – as individuals and groups – use to work out what knowledge is useful and helpful in our lives. How do we work towards developing open-access understandings of subjects which have become enclosed by classes of professional status – populations which have come to exclude the greater population from engaging in these fields ?

I am going to attempt to draw some sociological perspectives together with and around the practice of science and medical research to assist in clarifying the search for increasingly reliable understandings about the physical universe from dogmas of deference and dominance which alter behaviours in respect of attaining said understandings.

Table of Contents

Barriers between Scientific Establishments and Popular Culture

When things become professionalised and enclosed, there is a distancing effect of the involvement of the general population from their involvement in the field. Barriers are artificially created to discourage engagement and involvement in the given areas; recognition and interaction are gatekept by the order of people who have been told they are exclusive authorities under license from the establishment hierarchy. The fields of public science have become silos that exclude the majority of people from participation in perspectives of mind which we are born into (as an inherently owned part of our human capital) and exercise throughout our lives to greater or lesser extents. Here Dolby writes about the creation and maintenance of such barriers:

“Modem science has grown into a large-scale and complex activity. In an age of increasing bureaucracy and specialization, the knowledge construction industry is also bureaucratized and segmented. The intellectual divisions within science and between science and comparable activities, now hallowed by tradition, have become locked into the institutions of science, to be exploited by the relevant interest groups. Cognitive boundaries have thus been turned into social barriers. When these barriers were being built up, they could be justified in terms of a convergence of the cognitive requirements of efficient knowledge production and the social advantage they conferred upon insiders.

The arguments can conveniently be encapsulated in terms of the notion of expertise. In pure science, the more expert an individual is on a topic, the more he can be trusted as an authority. Expertise is acquired through specialist training, association with other experts and by making recognized contributions to knowledge relevant to the topic in question. The institutionalization of knowledge advancement particularly involves organizing the activity of individuals high in hierarchies of expertise. Any contribution to knowledge is ideally directed to those who can best appreciate it, that is, to those who are most expert. And contributions from those who are most expert are the most readily appreciated.

Informal communication networks naturally emerge among the elite of science; more formal institutions try to limit themselves to the higher part of hierarchies of expertise by setting minimum standards for participants in their activities. Any individual who fails to reach the minimum standards set by some scientific organization finds considerable barriers obstructing his participation in the activities of the science. His exclusion allows accredited scientists to interact more effectively.

Similar processes operate at the divisions between sciences, as claims of expertise tend to be limited to specific subject areas and skills. Thus, the institutionalization of separate sciences turns the separation between the hierarchies of expertise of each science into social barriers. As a consequence, the possibilities for overlap in the hierarchies of expertise are limited still further, and the segmentation of science is increased in a spiral of positive reinforcement. The tendency of intellectual barriers within and around science to cumulate and to become harder to cross has inevitably come to be recognized as a problem. ”

[Page 267 to 268, Dolby, R. G. A., (1982), On the Autonomy of Pure Science: The Construction and Maintenance of Barriers between Scientific Establishments and Popular Culture, in, Norbert Elias, Herminio Martins and Richard Whitley (ed,.j,Scientific Establishments and Hierarchies. Sociology of the Sciences, Volume VI, 1982. 267-292. Copyright © 1982 by D. Reidel Publishing Company.]

As smaller and smaller proportions of the population are given opportunity of the privileges necessary to become an actor in the field of medicine or the sciences, a gulf grows with the locked out populations due to their exclusion in knowledge production. The ignorant (i.e. consciously ignoring clear realities) colonial models of vertical hierarchies that shape the institutional spaces are corroding the institutions themselves – i.e. the living process of healthcare. Due to the distancing of populations from their involvement in science and medicine discourses there are increasing numbers of people who are abandoning any respect of science and medicine itself – a tragic course.

There are systems perspectives which suggest that creating such unquestioned ingroups and such ignored outgroups leads to terrible outcomes all round. What happens when people stop turning up at doctor surgeries for ailments which orthodox medicine easily treats ? What happens when medics are mandated not to continue researching new viable treatments (such as ginger for nausea) and can use only what the industrial-medical complex has defined as the tools for the job ?

What happens when the medical system – for example – has been constructed around male ideas and perspectives resulting in disaster for women in various health settings ? What happens when the medical system lacks appropriate mechanisms for taking onboard issues with its behaviour ? These are some of the questions our current predicaments necessitate ‘us’ asking as a culture.

Backdrop on Research Presented: Overdose and Psychiatry

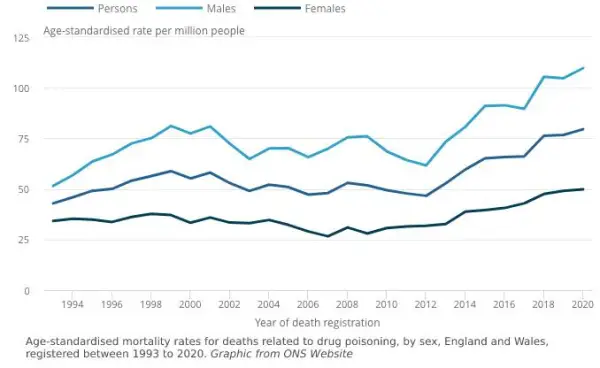

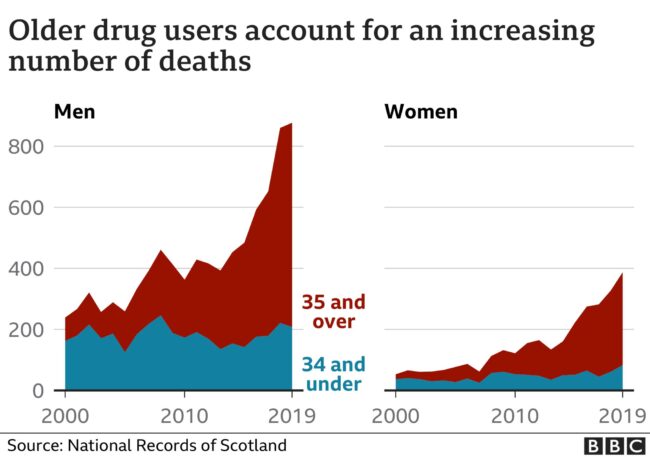

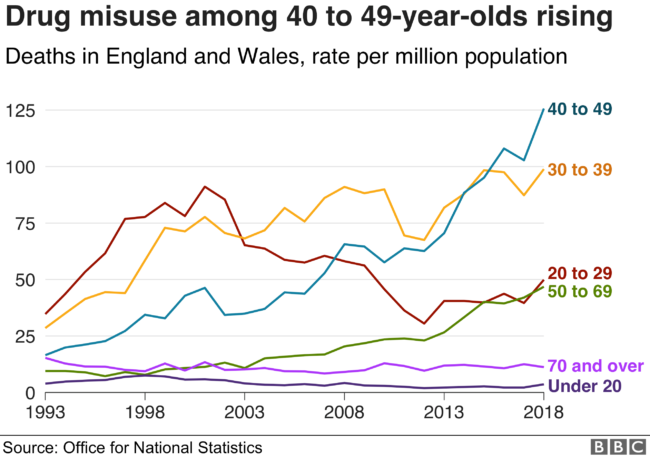

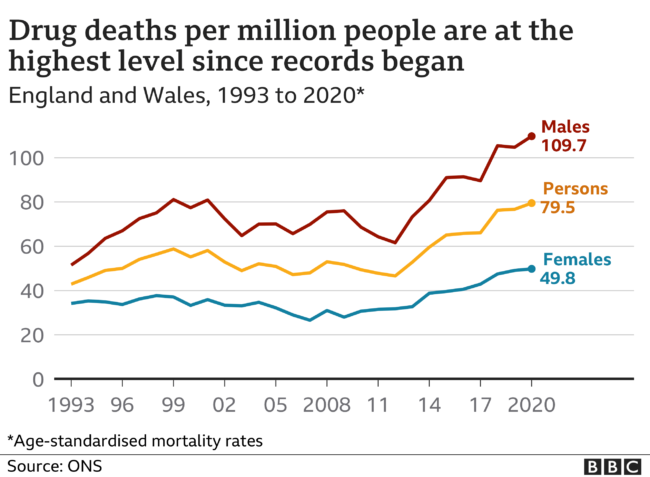

Over the past years, in the UK, we have seen a dramatic rise in the numbers of people who have a psychiatric diagnosis and also a dramatic number of the numbers of people who have died from drug related deaths. The social, medical and political response to these issues has resulted in failure unfortunately. Policy structures are scrambling to find new ways of approaching the issues especially as the strategy of criminalising drug use has resulted in criminalising populations who are most in need.

The ‘War on Drugs’ has turned out to be a policy disaster which was initiated by Richard Nixon’s American administration. John Ehrlichman who was Nixon’s chief of domestic policy at the time said:

“You want to know what this was really all about, The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

You can read the full interview with Ehrlichman Here

Criminalising people who use non-state sanctioned intoxicants started from an ideological drive to obtain a wedge vote in American politics. This form of divisive politics has had a tremendously damaging effect on society resulting in the marginalisation and demonisation of large groups of people. At the moment, due to the deepening of poverty and widening distance between those who are at the bottom of the socio-economic spectrum and those who live above a sufficiency level, we are seeing the hall marks of people increasingly self medicating as responses to stress and misery.

Professor Alex Stevens was a part of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs and was involved in producing the report ‘Reducing Opioid-Related Deaths in the UK’ published in December 2016. He says in a recent drug policy conference that the evidence which was brought together was not acted on. In the following keynote presentation at the Drugs Research Network Scotland, he articulates drug related deaths in terms of class and discusses how drug policy is shifted away from evidence bases towards morality ideologies:

Drugs as Surrogates to Natural Reward: Barriers to Progressive Policies

In my experience of attending public consultations and research events on drug and alcohol policy, due to the scale and complexity of the issue, it looks like there is resistance to engaging issues such as structural violence, a lack of an overarching toxicological framework for understanding contributing factors to overdose, and the highlighting of therapeutic avenues which mitigate the damaging effects of taking drugs.

Drug taking, in terms of intoxication, has an intimate relationship with states of perception which involve the reward systems of the nervous system. Intoxication has long served multiple cultural roles in terms of entertainment, socialising and perspective shifting. Alcohol in many cultures has been a standard of socialising and the forming of bonds, and instated in rituals such as wedding rites – the word Honeymoon comes from the drinking of mead (an alcoholic beverage made from honey) – it functions in distinct ways as a means of social cohesion.

In different places different intoxications are considered social giving rise to context specific social prescriptions; for example, in some places alcohol is an illicit drug but cannabis is used in social settings as the form of intoxication which gets the cultural seal of approval. The issues seem to occur when people are involved in problem use of a drug – ones which produce medical ailments.

There is a growing body of evidence that problem drug use is associated with forms of self medication where individuals use drugs to respond to depressing life circumstances. Di Chiara and colleagues give an account of how drugs offer biochemical surrogates of natural reward systems and offer us a potential framework for understanding problem drug use:

“Drugs of abuse act on specific neurotransmitter pathways and by this mechanism elicit neurochemical changes that mimic some aspects of the overall pattern of the neurochemical effects of natural rewarding stimuli. Thus, drugs of abuse are biochemically homologous to specific aspects of natural rewarding stimuli. The behavioural similarity between drugs of abuse and natural stimuli, including that of being rewarding, results from their common property of activating neurochemically specific pathways.

Natural stimuli accomplish this result indirectly through their sensory properties and incentive learning while drugs stimulate by a direct central action the critical reward pathways. Many drugs of abuse mimic the incentive properties of natural stimuli and their ability to stimulate mesolimbic dopamine pathways. Both natural rewards and drugs of abuse, including amphetamine, cocaine and other psychostimulants, preferentially stimulate dopamine transmission in the mesolimbic nucleus accumbens compared with the dorsal caudate, an area related to the extrapyrimidal motor system…

A basic property of drugs of abuse is that of promoting behaviours that tend to increase the probability of coming into contact with the drug leading to drug seeking behaviour. In fact drugs of abuse are rewarding and their action results in feelings of pleasure or reduction of dysphoria and anxiety that correspond to the subjective reports of ‘high’, ‘euphoria’ and ‘relaxation’ after their acute administration. To clarify the mechanism of the positive reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse, two premises can be made. The first is that drugs do not invent anything but simply act on mechanisms and processes that the organism utilizes during its normal functioning. The second is that biological mechanisms are the result of a developmental history (phylogenesis) having the goal of improving the adaptation of the organism to the environment, thus ensuring survival of the species”.

[Di Chiara, G., Acquas, E., Tanda, G., Cadoni, C. (1993), ‘Drugs Of Abuse: Biochemical Surrogates Of Specific Aspects Of Natural Reward?’ In Wonnacott, S., & Lunt, G. G. (Eds.) Neurochemistry Of Drug Dependence, London: Portland Press, Biochemical Society (Great Britain). Symposium Royal Free Hospital (London, England), https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Neurochemistry_of_Drug_Dependence.html?id=MpJeAQAACAAJ&redir_esc=y]

Thus, dire and chronic poverty of one form or another may prime someone to seek out drug intoxications for the purposes of “reduction of dysphoria”. For example, people who may be living in fuel poverty, working in precarious zero hour contracts and who may be oppressed by their employer and/or partner may be biochemically primed by stress to seek out intoxications to reduce the dysphoria of their life circumstances. The criminalising of people in the UK for smoking cannabis etc as a social response to a dysfunctional societal settings is adding to the impetus to self medicate.

The result is often what gets called polypharmacy – the individual might end up taking intoxicating psychiatric drugs via the prescription pad as well as the intoxicants which are used in social settings and as social settings. The medical system, however, has no overarching toxicological framework to understand how different drugs interact, accumulate and which can ultimately overwhelm the systems the body uses to metabolise drugs, resulting in overdose.

A complicating factor in approaching these complex and tangled issues I heard at a high level alcohol policy conference. Someone involved in organising the conference which brought contributors from across Europe to talk about managing the effects of alcohol in our culture, told me about how their work is a mine field.

As an example, when it became clear that the health impacts of alcohol are outlier large, the Scottish Government made the move to introduce minimum unit pricing. This policy had major effect in relation to the cheap and toxic ‘ciders’ which were available but little effect on the price of more expensive beverages; the positive health outcomes were clear but the alcohol lobby in the form of the ‘Scottish Whiskey Association’ attempted to sue the government.

The net result of large financial players suing governments for introducing measures which protect the health of their citizens is that progress is made slow and very expensive. Even notionalising the advice to eat a good meal before you go out drinking to protect your brain and liver becomes riven with hazards. The evidence that alcohol is a carcinogen (a substance which causes cancer) soon becomes something to sidestep by cancer research charities and institutions to ensure that further much needed research can continue.

It seems like medicine and scientific research are not just policy and rubric bound, but they are also the target of industry bodies which threaten the livelihoods of those in medicine trying to make constructive differences. It seems apparent that political and economic forces are playing much more powerful roles in cultural decision making than is scientific evidence at the moment. This compounds the insularity of the medical and academic world and shapes the offerings which emerge around these issues.

Independent Research of N Acetyl Cysteine

Having seen up close the rigid, fragile and precarious nature of policy and practice around issues of drug use, I set out a series of research projects to explore what possible therapeutics are worth exploring as potential solutions. As an independent researcher I started to look at the systems which the body uses to detoxify drugs (also known as xenobiotics).

Chief amongst the systems which the body uses to detoxify drugs came the enzyme glutathione. Arthur J. L. Cooper published detailed studies on how: “Within the last few years it has become apparent that glutathione (GSH) plays a particularly important role in protecting the brain against oxidative stress and against potentially harmful xenobiotics, including some drugs and drug metabolites that can cross the blood-brain barrier.”

[Cooper, J. L., (2020) Role of Astrocytes in Maintaining Cerebral Glutathione Homeostasis and Protecting the Brain Against Xenobiotics and Oxidative Stress in, Shaw, C. A., (2020) Glutathione In The Nervous System, CRC Press]

What particularly interested me in further exploring this thread of research was the fact that a simple protein called N-acetyl cysteine is and has been used to treat overdoses in accident and emergency departments around the world for over 5 decades. It is a generic medicine and natural molecule which means that companies cannot profit from monopoly rights and that it can be produced cheaply around the world. It is listed in the British National Formulary and the Martindale – two key textbooks used in British medicine.

All these factors offered up good reason to bring together and examine what research there had been done relating n-acetyl cysteine, drug use and psychiatry/psychology. With five decades of use there is an abundance of history with which to make an assessment of how well tolerated it is by the body and to examine if there are any reasons why this might not be used in a given context (the contra-indications).

As well as this, because the drug n-acetyl cysteine goes on to convert into the enzyme found in the body called glutathione, there is an extra level of information in biochemistry which is available to the researcher to examine and cross reference its effects. It is not enough to know that a substance works, what is of equal importance is to know how a substance is working in medicine (by detailing mechanisms of action).

This work has been brought together as a part of a larger study tracing the biochemical rationales for why n-acetyl cysteine works as it does. The stepwise progression of the research has indicated that n-acetyl cysteine does not just act through removing drugs (xenobiotics) from the system but also functions via stabilising glutamate signaling which is well known to be implicated in forms of addiction and psychological disorder.

The work of Christopher A. Shaw goes as far as to propose glutathione itself as a neurotransmitter detailing the multiple roles it plays in the nervous system. Considering that many drugs are known to produce reactive oxygen species (free radicals) and that many drugs are metabolised and eliminated from the system via glutathione biology, it seems like this may offer an account of how chronic drug use can factor into and/or produce psychological dysfunction.

[Shaw, C. A., (2020) Multiple Roles of Glutathione in the Nervous System, in, Shaw, C. A., (2020) Glutathione In The Nervous System, CRC Press]

This research project offers clear potential therapeutics for drug users which may save lives; not only this but it also demonstrates that n-acetyl cysteine has proven application in relation to psychological ailment. Although this will not alleviate chronic proverty and inequality, it may offer individuals potential improvements in their standard of life and prevent overdoses. N-acetyl cysteine is available from nutritional shops and has a further advantage of not being a prescription only drug.

Verbatim Science Document: N Acetyl Cysteine Map of Research

What follows is an example of the verbatim science methodology where papers and publications are drawn upon verbatim and where the excerpts are organised together to illustrate themes which run through the literature. The aim of the methodology is to extract word-for-word highlights from peer reviewed science papers to bring together an assemblage helpful for opening up dialogue around the given focus. This removes a barrier of language creation where the reader is given a greater understanding via the original content.

The methodology is an exploration of the tools we can use to build meaning by extending our memory and organising information. This method is a means of excavating and integrating existing publications prior to creating a unique piece of narrative prose which has been the mainstay of academic science with its adjunct bibliographic convention.

This was made by using Xmind Pro to generate the mind map in PDF format. Then the PDF was embedded into a Miro board which allows for vector images. On top of the pdf mindmap I then placed links to the papers themselves so to aid the researcher by taking them directly to the original information sources.

The easiest way to navigate the mind map is to use a mouse and scroll wheel to move about and to zoom in and out. You can make the Miro board full screen via the controls you find in the bottom right hand corner of the Miro embed. You can visit the papers which are the focus of the work by clicking on the grey ‘View Paper’ buttons.

I am also including an indexed document created from the mind map via Xmind Pro. The combination of the two types of document will assist the reader in navigating through the information both in linear and non-linear ways. This is a particular multimedia project focused on examining the different tools and technologies which enable knowledge building and extending our memory via the process of organising information.