Educational History: Leo Tolstoy 1828 to 1910

“I put men to death in war, I fought duels to slay others. I lost at cards, wasted the substance wrung from the sweat of peasants, punished the latter cruelly, rioted with loose women, and deceived men. Lying, robbery, adultery of all kinds, drunkenness, violence, and murder, all were committed by me, not one crime omitted, and yet I was not the less considered by my equals to be a comparatively moral man. Such was my life for ten years.”

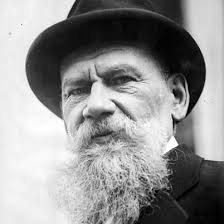

Leo Tolstoy is one of the most well-known Russian writers, revered as one of the greatest novel writers in the world. The most famous of his works are the novels “War and Peace” and “Anna Karenina”. He was also a respected educator and religious thinker, whose authoritative opinion was the cause of a new moral and religious current – Tolstoyism. Leo Tolstoy had a profound influence on the evolution of European humanism, as well as on the development of the realistic tradition in world literature.

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy was born in 1828 in Yasnaya Polyana, in the Tula Province of Russia, as a descendant of two distinguished families. He was the fourth of five children of Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy, a veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812, and Countess Mariya Tolstaya (née Princess Volkonskaya).

His mother was a daughter of Nikolai Volkonsky, Tsarina Catherine the Great’s general, member of the famous Russian, from Rurikid princely house. Leo’s paternal ancestor, Count Peter Andreyevich Tolstoy was known for his role in the investigation of death of the Tsarevich Alexei.

Leo’s father was a member of a military campaign against Napoleon, and participated in the “Battle of the Nations” at Leipzig. He was later a prisoner of the French. When Leo was not yet two years old his mother died in 1830, six months after the birth of her daughter. In 1837 the family moved to Moscow and soon after his father Count Nikolay Tolstoy died suddenly, so all the orphaned children were brought up by relatives.

Three years later all five siblings were moved again, now to Kazan to their father’s sister, a member of the Yushkova family. The family was considered one of the most fun in Kazan, all family members were girthed by glamour and fame. Although Tolstoy experienced a lot of loss at an early age, he would later idealize his childhood memories in his writing.

Leo Tolstoy wanted to shine in society, but he was prevented by natural shyness and a lack of visual appeal. “Philosophizing” about the most important issues of our being for example: happiness, death, God, love and eternity was a delayed effect on his character in that period of life. He recognized the diverse nature of his thinking. Tolstoy received his primary education at home, at the hands of French and German tutors. In 1843, he enrolled in an Oriental languages program at the University of Kazan. In 1844 he began studying but he had difficulties with his “Turkish-Tatar language” transition exam and had to re-pass the first year program.

His teachers described him as “both unable and unwilling to learn”.

To avoid a full repetition of course he went to law school, where his problems with grades in some subjects continued. Tolstoy ultimately left the Kazan University in the middle of his studies in 1847 without a degree. He returned to his parents’ estate, where he made a go at becoming a farmer. Tolstoy was trying to establish a new relationship with his peasants. In 1861 peasants received their liberty in the Russian Empire. Before that date the owner could sell them with the land as a part of the property.

Furthermore, in 1849 Tolstoy opened the first school for peasant children. The main teacher was Fock Demidovich, but Tolstoy also often gave lessons. In the autumn of 1851 Tolstoy passed the exam in Tiflis and he became a cadet in the 4th Battalion of the 20th Artillery Brigade, stationed in the Cossack village on the bank of the Terek Starogladovskaya under Kizlyar. With some changes in the details it is depicted in the novel “The Cossacks”. As a cadet Leo Tolstoy remained two years in the Caucasus and then he was transferred to Sevastopol in Ukraine in November 1854, where he fought in the Crimean War through August 1855.

Tolstoy in spite of all life’s hardships and the horrors of the siege, he wrote the story “Chopping wood”, which reflected the Caucasian experience, and the first of three “Sevastopol Stories” – “Sevastopol in December 1854”. He sent the story to “Contemporary”, the most popular journal of the time, and was quickly published and read with interest throughout Russia, delivering an awesome experience by painting the horror that befell the defenders of Sevastopol. The story was shown to Russian Emperor Alexander II, and he told the officer to take care of the “gifted”.

For the defense of Sevastopol Tolstoy was awarded the Order of St. Anne 4th degree medal with the inscription “For Bravery”, “For defense of Sevastopol 1854-1855” and “In memory of the war of 1853-1856”. Subsequently, he was awarded two medals “In memory of the 50th anniversary of Sevastopol defense”: silver as a member of the defense of Sevastopol and bronze as the author of “Sevastopol Stories”.

Once the Crimean War ended and Tolstoy left the Army, he returned to Russia. Back home, the burgeoning author found himself in high demand on the St. Petersburg literary scene. Stubborn and arrogant, Tolstoy refused to ally himself with any particular intellectual school of thought. Declaring himself an anarchist, he made off to Paris in 1857, but a trip made rather a negative impression on Tolstoy.

“Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.”

In the autumn of 1859 Tolstoy once again opened his school for peasants in a single room of his large manor house at Yasnaya Polyana. At the time, free education for peasant children did not exist in Russia. The subjects were elementary, the method a mixture of blows and learning by heart, and the results negligible. This situation Tolstoy wished to remedy by substituting public education based on entirely original pedagogical methods.

“On the Problems of Pedagogy,” he wrote: “For every living condition of development, there is a pedagogical expediency, and to search this out is the problem of pedagogy.”

In 1860, Tolstoy wrote to his friend Y.P. Kovalevsky: “I’ve been busy with a school for boys and girls…progress…has been quite unexpected. […] The most vital need of the Russian people is Public education… [This] hasn’t begun, and never will it begin as long as the government is in charge of it.” In May 1862 back in Russia from his second tour around Europe, Leo Tolstoy suffered from depression and on the recommendation of doctors went to Bashkir Karalyk farm, in Samara Province.

He lived there in the Bashkir tent (yurt), ate lamb, sunbathed, drank mare’s milk, tea, and played checkers, but still remembered how he talked with children on the European streets. He found them very smart and intelligent, free-thinking, and surprisingly well informed, but with no thanks to their schooling. In an article entitled “On National Education” he wrote:

“Here is an unconscious school undermining a compulsory school and making its contents almost of no worth…. What I saw in Marseille and in all other countries amounts to this: everywhere the principal part in educating a people is played not by schools, but by life.”

After return to his estate Tolstoy began to publish the pedagogical journal “Yasnaya Polyana”, the first of a 12 issue-installment and marrying a doctor’s daughter named Sofya Andreyevna Bers the same year. In addition to theoretical articles, he also wrote a number of stories, fables and transcriptions adapted for elementary school. Tolstoy took up educational reform before the emancipation of the peasants and actively participated in live of his school and Yasnaya Polyana. At that time, after reading Montaigne, he wrote:

“In education, once more, the chief things are equality and freedom.”

In 1862, Tolstoy had opened about twenty schools on his lands, and over fifty young boys, girls, and not infrequently some adults attended lessons. Yasnopolyanskaya School belonged to a number of teaching experiments: in the era of reverence for the German School of Education, Tolstoy strongly rebelled against every regulation and discipline in the school. He believed that all education should be free and voluntary.

Tolstoy thought that all teaching must be done individually between the teacher and the student and their mutual relations. In the Yasnaya Polyana school children sat where everyone wanted, as much as they wanted.

There was no specific teaching program, but during the morning children were taught elementary and advanced reading, composition, penmanship, grammar, sacred history, Russian history, drawing, music, mathematics, natural sciences, and religion. In the afternoon there were experiments in physical sciences and lessons in singing, reading, and composition.

No consistent order was followed, and lessons were lengthened or omitted according to the degree of interest manifested by the students. On Sundays, the teachers met to talk over the work and lay out plans for the following week. But there was no obligation to adhere to any plan, and each teacher was placed entirely on their own. For a time they kept a common diary in which were set down their failures with merciless frankness as well as their successes.

Children learned new ideas, science and art, but Tolstoy’s attacks on European education and “progress” brought many to conclude that he was very “conservative”. The only problem in the school was that the teachers had to motivate the peasant’s children. Things were going well. Tolstoy himself led them with a few permanent teachers and a few outside inputs from closest friends and visitors.

The moral and religious teaching of Leo Tolstoy was based on the idea of non-resistance to evil and desire to spread good in the world for every person. He proposed the idea of moral revolution, which was based on the thesis of free self-improvement. He argued that non-violent spiritual revolution can happen quickly in a person. Leo Tolstoy’s terms of moral education are: development of observation, developing the ability to think independently, to feel deeply and the development of creativity. He also stood for children’s freedom of activity and creative work, and respect for the child as an individual. Tolstoy protested against the oppression of children, for him familiarizing the child was a “religious principle”.

Based on the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideal nature of the child (the view that imperfect society and adults spoil the child with “fake” culture), Leo Tolstoy argued that teachers do not have the force of law to educate children in the spirit of their adopted principles. The basis of education should be based on students’ freedom of choice – what and how they want to learn. Teachers should follow and develop the nature of the child.

For Leo Tolstoy, an education system is a free connection of people, with a certain amount of knowledge, where both share freely. The main task of training and education was the development of creative thinking, and argued the need for a full-fledged science education.

He defended the thesis of the unity of education and training. It is impossible to educate without transferring knowledge; all knowledge is valid for education. The most important thing in education, according to Leo Tolstoy, is the observance of the conditions of freedom in education and training, on the basis of religious and moral teachings.

Education should be fruitful and promote the movement of man and mankind to an ever greater good. A special role is given to such methods of teaching as a teacher’s words, stories and conversation. Extensive use of excursions, experiments, tables, pictures, and watching authentic items were a feature of his thinking. Critical importance was placed upon the phonetic method of teaching literacy.

Soon Tolstoy left teaching. Marriage, birth of their children and planning a novel created new activity for him. Residing at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy spent the better part of the 1860s toiling over his great novel “War and Peace”. Both critics and the public were buzzing about the novel’s historical accounts of the Napoleonic Wars, combined with its thoughtful development of realistic yet fictional characters.

In the early 1870s Leo Tolstoy began to create his own “ABC” for children and published it in 1872. He then released his “New ABC” and a series of four “Russian books to read”, approved as aids for primary school as a result of a long dialogue with the Ministry of Public Education.

Following the success of “War and Peace”, in 1873, Tolstoy set to work on the second of his best known novels, “Anna Karenina”. The novel was partially based on current events, and also fictionalized some biographical events from Tolstoy’s life. The first sentence of “Anna Karenina” is among the most famous lines of the book: “All happy families are alike, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”. Also from the same book came very powerful quote:

“To educate the peasantry, three things are needed: schools, schools and schools.”

Despite the success of “Anna Karenina”, following the novel’s completion, Tolstoy suffered a spiritual crisis and grew depressed. Struggling to uncover the meaning of life, Tolstoy first went to the Russian Orthodox Church, but did not find the answers he sought there. He came to believe that Christian churches were corrupt and, in lieu of organized religion, developed his own beliefs. He decided to express those beliefs by founding a publication called “The Mediator” in 1883. As a consequence of espousing his unconventional – and therefore controversial – spiritual beliefs, Tolstoy was ousted by the Russian Orthodox Church. He was even watched by the secret police.

When Tolstoy’s new beliefs prompted his desire to give away his money, his wife strongly objected. The disagreement put a strain on the couple’s marriage, until Tolstoy begrudgingly agreed to a compromise. He conceded to granting his wife the copyrights – and presumably the royalties – to all of his writing predating 1881. In addition to his religious tracts, Tolstoy continued to write fiction throughout the 1880s and 1890s.

Among his later works’ genres were moral tales and realistic fiction. One of his most successful later works was the novella “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”, written in 1886. In 1898, Tolstoy wrote “Father Sergius”, a work of fiction in which he seems to criticize the beliefs that he developed following his spiritual conversion. The following year, he wrote his third lengthy novel, “Resurrection”. While the work received some praise, it did not match the success and acclaim of his previous novels.

Tolstoy’s other late works include essays on art, a satirical play called “The Living Corpse” that he wrote in 1890, and a novella called “Hadji-Murad” (written in 1904), which was discovered and published after his death. Over the last 30 years of his life, Tolstoy established himself as a moral and religious leader. His ideas about nonviolent resistance to evil influenced the likes of social leader Mahatma Gandhi.

During his later years, Tolstoy reaped the rewards of international acclaim. Yet he still struggled to reconcile his spiritual beliefs with the tensions they created in his home life. His wife not only disagreed with his teachings, she disapproved of his disciples, who regularly visited Tolstoy at the family estate.

Their troubled marriage took on an air of notoriety in the press. Anxious to escape his wife’s growing resentment, in October 1910, Tolstoy and his daughter, Aleksandra, embarked on a pilgrimage. She served as her elderly father’s private doctor during the trip.

Valuing their privacy, they traveled incognito, hoping to dodge the press, to no avail. In November 1910, the stationmaster of a train depot in Astapovo, Russia opened his home to Tolstoy, allowing the ailing writer to rest. Tolstoy died there shortly after. To this day, Tolstoy’s novels are considered among the finest achievements of literary work. “War and Peace” is, in fact, frequently cited as the greatest novel ever written.

This article and history was written by Dominik Omiecinski