Education History: A Brief History of Ragged Schools

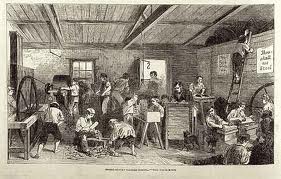

Ragged schools is a name commonly given after about 1840 to the many independently established 19th century charity schools in the United Kingdom which provided entirely free education and, in most cases, food, clothing, lodging and other home missionary services for those too poor to pay. In many ways the movement embodied the notion of education as human development.

Often they were established in poor working class districts of the rapidly expanding industrial towns. Lord Shaftesbury eventually came to be the chairman of Ragged schools and championed the movement for thirty nine years. Several different schools claim to have been the first truly free school for poor or ‘ragged’ people but free education is a tradition which spans time and culture.

John Pounds (1766- 1839), a Portsmouth shoemaker is cited by Thomas Guthrie as the founder of the Victorian movement. Pounds was dedicated to the children he taught, fed and gave place to in the town so much so that the Reverend Henry Hawkes wrote a collection of memoirs on his recollections of this good soul. He provides one of the earliest well documented example of the movement notably in his ‘A Plea for Ragged Schools’.

The ‘crippled cobbler‘ as he was sometimes called, began teaching poor children without charging fees, in 1818. Rev Dr Thomas Guthrie (1780-1873) of Edinburgh was also an early promoter of free schooling for working class children. He started one of the first Scottish free schools for the poor.

Sheriff Watson established another in Scotland in 1841, in Aberdeen – initially for boys only, until its sister school opened 1843 for girls, and a mixed school in 1845. From here the movement spread to Dundee and other parts of Scotland, partly by the work of Thomas Guthrie.

Close to London, the tailor Thomas Cranfield offered free schooling to the poor at an early date. Having gained educational experience at a Sunday school on Kingsland Road, Hackney, near London, in 1798 he established a day school on Kent Street near London Bridge and began to admit significant numbers of poor children without any payment.

By the time of his death in 1838, he had built up an organization of nineteen Sunday, night and infants schools situated in the poorest parts of London that offered their services free to many children of poor families, and destitute children.

Adoption of the name ‘Ragged School’ The term Ragged School appears to have been first introduced by the London City Mission. Beginning in 1835, it appointed paid missionaries and lay agents to assist the poor with a wide range of free charitable help from clothing to basic education (including Penny Banks, Clothing Clubs, Bands of Hope, and Soup Kitchens).

In 1840 the London City Mission used the term ‘ragged’ in its Annual Report to describe its establishment that year of five schools for 570 children. These had, it reported, been ”formed exclusively for children raggedly clothed’.

Charles Dickens’ visit to the Field Lane Ragged School in 1843 inspired him to write A Christmas Carol. Appalled by what he saw at Field Lane (now Farringdon Road), he initially intended to write a pamphlet on the plight of poor children, but realised a story would have more impact.

By 1844 there were at least twenty free schools for the poor in London maintained by the London City Mission, by the work of chapels, and philanthropists. An association was suggested to share experience and promote their common cause. To this end four people (Locke, Moutlon, Morrison and Starey) connected to the existing free schools formed a steering group.

The Ragged Schools Union

In ‘Sixty Years of Waifdom’, C.J. Montague wrote about the formation of the Ragged School Union. Four men met and prayed together in a private house off the Gray’s Inn Road. On April 11th, in 1844, Mr Locke, a wollen-draper; Mr. Moulton, a dealer in second-hand tools; Mr. Morrison, a City Missionary, and Mr Starey formed the beginnings of the Ragged Schools Union.

At this gathering they resolved “to give permanence, regularity and vigour to existing Ragged Schools, and to promote the formation of new ones throughout the metropolis, it is advisable to call a meeting of superintendents, teachers and others interested in these schools for this purpose.”

The Ragged Schools Union was duly established; it later became the Shaftesbury Society (since 2007 part of Liveability). Wealthy individuals such as Angela Burdett-Coutts gave large sums of money to the Ragged Schools Union.

The Ragged School Union begun with about 200 teachers in 1844. This grew to about 1600 teachers by 1851. By 1867, some 226 Sunday Ragged Schools, 204 Day Schools and 207 Evening Schools provided a free education for about 26,000 pupils.

The chairman for the first 39 years of the Ragged Schools Union was the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, and in this time an estimated 300,000 destitute children received a free education. Under his chairmanship, the free school movement became respectable, even fashionable, attracting the attention of many wealthy philanthropists.

Above you can see Laura Mair talking about the focus of her research on the Ragged Schools. Having fulfilled her studies at the University of Edinburgh she published one of the most significant modern historical documents of the Ragged Schools movement making the relationships between people the focus of her study. You can buy her book ‘Religion and Relationships in Ragged Schools: An Intimate History of Educating the Poor, 1844-1870‘ from Routledge publishers.

You can also download a copy of her PhD for free here:

Eager (Eager, W. McG. 1953 Making men: the history of Boys Clubs and related movements in Great Britain, London: University of London Press) explains, the Earl of Shaftesbury gave what had been a Nonconformist undertaking the cachet of his Tory churchmanship – an important factor at a time when even broad-minded (Anglican) churchmen thought that Nonconformists should be fairly credited with good intentions, but that co-operation (with them) was undesirable.

The success of the Ragged Schools demonstrated vividly that there was a demand for education amongst the poor. After 1870 public funding began to be provided for free elementary education amongst working people.

As the board schools were built and funded under the Elementary Education Act 1870 (The Forster Education Act): the Board Schools became the legacy of the Ragged Schools. The movement helped to establish 350 ragged schools by the time the 1870 Education Act was passed. Over the next years ragged schools were gradually absorbed into the new Board Schools.

Today, a Ragged School Museum is open (founded 1990), at Copperfield Road, Tower Hamlets. It occupies buildings were previously used by Dr Barnardo to house what is said to have been the largest Ragged School in London. The history of the Ragged schools is extensive and arguably involved in different forms, involvement from every part of UK culture.

What is most interesting is the plurality of responses to education which rose from many quarters of society recognising the importance for people’s health, happiness and prospects. It is clear to see from history that there were such benefits to be seen from universal free education.

Further Reading:

Source: http://www.barnardos.org.uk/barnardo_s_history.pdf

Source: http://www3.westminster.gov.uk/docstores/publications_store/archives/schools.pdf