Romantic Radicals and Agrarian Futurists: John Hargrave, the Kibbo Kift and Beyond by Anne Fernie

Anne Fernie shared a second talk on the history of countercultures and romantic radicals on February 11th 2016 at the Castle Hotel. Having spent a lifetime reading and learning about the histories which have helped shape our culture and world today. Here you can read the transcript which matches up with the slideshow she did.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Fundamentally, the presentation concerns itself with ‘the great outdoors’ and England’s relationship with it. It is effectively a companion piece to a prior ‘Ragged’ presentation ‘The Origin of Hippie in Europe 1880-1940 (see on: http://tinyurl.com/jrfwxss) which focused on the hearty yet mystical German ‘Naturschwärmer’ experience. Although there was much cultural exchanging during the period under examination, the English movements have their own unique and more circumspect flavour with the ‘crank’ a well-loved manifestation of it.

So whether the characters we meet are ‘mad, bad’ or were even ‘dangerous to know’ is well, up to you……….

Slide 2: ‘Cranks’

After a quick contextual look at the situation in England with the advent of the industrial revolution, we will focus on the later 19th century through to the 1930s, starting in the Edwardian era which saw a vein of ‘melancholic nostalgia’ appear in novels and commentaries. Urban life was viewed pessimistically and negatively and questions asked regarding the nature of English cultural identity which seen to be under threat by rapid urbanisation. ‘Englishness’ was seen as being rooted in the countryside.

Slide 3: Robert Owen (1771 to 1851)

What is particularly ‘English’ is that from the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution these concerns went hand in hand with what became known as ‘utopian socialism’ long before the concept of ‘Socialism’ was formalised. In a period that encompassed both the U.S war of independence & the French Revolution, as well as the misery engendered by the end of the Napoleonic wars.

Human rights, equality and democracy were becoming urgent issues and enlightened individuals such as Titus Salt and Robert Owen (both mill owners) were appalled at the working conditions within industry. They worked to create experimental ‘model’ communities at their textile mills: Owen’s New Lanark, in central Scotland and Salt’s Saltaire, in Lancashire (both now World Heritage sites).

Owen set out his case for radical social reform in ‘A New View of Society: Essays on the Principle of the Formation of the Human Character’ (1813). The publication was a protest against the condition of the British poor – three quarters of the population – and a call for educational, industrial and social reform. Owen believed that harsh conditions in factories were damaging to people and that machines should serve the people, rather than the other way around.

Owen soon became a pioneer of nursery or early years education, setting up a schoolroom on the site where children would be educated before they began work in the mill – this, 70 years before formal and compulsory education for all was introduced in Britain. The on-site shop bought goods in bulk, keeping retail costs of the good quality merchandise down. The savings were passed to the workers which pre-dated the later co-operative movement.

From 1817, Owen fully embraced socialism & submitted a report to the committee of the House of Commons on the Poor Law. Owen argued that the underlying cause of distress was the competition of human labour with machinery, and that the only effective remedy was the united action of men and the subordination of machinery together with the establishment of model communities like his own at Lanark.

Together with initiatives such as Owen’s, seeds of ecological and environmental thinking began to appear in Europe & England in the 17th and 18th centuries, in reaction to the exploitation of the land and communities precipitated by the Industrial Revolution. Artists such as William Blake raged against the dehumanizing effect of industrial ‘Dark Satanic Mills’; John Ruskin urged the mid-19thc artist to get out of his studio and into nature and William Morris’ Arts and Crafts movement promoted individual, crafting skills rather than the mechanized production of furniture, fabrics and design.

Slide 4: Utopian Socialist & ‘Crank’: Goodwyn Barmby (1820 to 1881)

Goodwyn Barmby is the first of two Chartist Utopian Socialist cited in this presentation and a follower of Owen’s concepts of a New Moral World. Both men were also aware of the French utopian socialist pioneer Charles Fourier (1772-1837) and his ideas for founding utopian communities. Chartism was the first truly working class movement that actively campaigned for six key rights including the vote for all over 21s. that MPs should not have to be property owners and establishment of the secret ballot. The movement emerged in 1836.

Barmby claimed credit for founding the East Suffolk and Yarmouth Chartist council in September 1839 and remained an active chartist until the early 1840s when he lost his taste for radical politics.

He visited Paris in 1840 to study social organisation and upon his return, married and with his wife Catherine, founded the Communist Propaganda Society in 1841, declaring that date to be Year One of the new ‘communist calendar’. Barmby founded and wrote the monthly Communitarian Apostle from 1842 which promoted rational marriage and universal suffrage. He also lectured at the ‘communist temple’ at Marylebone Circus.

In 1843 he founded the ‘Communist Chronicle’ which supported the German communist Wilhelm Weitling. The Communitorium became the Communist church by 1844 but by 1848 was becoming disillusioned with communism and starting preaching as a Unitarian, holding his post of minister in Wakefield for 21 years from 1858, actively involved in local liberal politics, agitating for parliamentary reform, and women’s suffrage. He was also a successful writer of pastoral in the 1860s. One sees the emergence of (now familiar) lifestyle reforms that apparently went hand in hand with the then radical political and social ideals: Barmby too promoted what are now regarded as ‘New Age’ ideals of vegetarianism, hydrotherapy, long hair, and sandal wearing.

Excerpt from Barmby’s ‘this is now the winter’s time’ (1851)

…..This is now the winter time,

Remember, workers, then,

That none should starve while others have,

That Christ in winter came to save,

And, but in no alms-taking way,

Accept your rights on New Year’s day.

This is now the winter time,

My gallant working men.

Slide 5: Punch cartoons

Early lifestyle pioneers were soon labelled as crankish. The slides for example show how early satirical magazines such as Punch pounced on non-conformist ideas such as vegetarianism as early as the 1850s. This mockery of socialism as a haven of crankery continues today as articles and photos deriding Michael Foot’s wayward hair and ‘donkey jacket’ and Jeremy Corbyn’s shell suit illustrates (Corbyn is also a member of the Woodcraft Folk – we shall come to them later on…).

Slides 6 & 7: Dr William Price (1800 to 1893)

An early innovator and pioneer whose legacy has been tarnished by his perceived ‘crankishness’ is Welsh nationalist, republican and one of the youngest ever fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons, Dr William Price.

Born in Rudry, near Caerphilly, in 1800 he could not speak or read a word of English when he started school at the age of 10 yet became a qualified surgeon in 1821& was one of the first doctors to advocate non-smoking, exercise and vegetarianism. He also rejected marriage as an institution that condemned women to servitude.

In 1827 he moved to Nantgarw and became the surgeon for ironmaster Francis Crawshay, practising medicine at the Brown Lenox chainworks & setting up a proto health service there by getting the workers to pay a levy each week which would pay for their care when they were ill. He also established one of the first co-op stores in the town. He rejected contemporary medical practices such as bleeding & purging and performed one of the first skin-graft operations on an injured worker.

Dr. Price was ever in and out of the courts, both as a defendant and petitioner. He was charged with the manslaughter of a patient and had his father’s body exhumed to prove mental illness. Possessing an extensive knowledge of the law, and draped in a shawl of royal tartan, he would conduct his own defence brilliantly to the crowded gallery. He also opposed vaccination, in part due to his brother’s childhood death following an inoculation, and refused to treat patients who smoked. He was an advocate of vegetarianism, believing that eating meat “brought out the beast in man”, and denounced vivisection.

He was a leader in the failed Chartist rising of 1839, but condemned the use of force and was had to flee to France disguised as a woman. It was there that he had a mystical experience in the Lourvre and realised that the future belonged to Druid people. . He named himself the Son of the Primitive Bard, a high order of druid, and the prophecy claimed his son would be the next ruler of the earth.He owned a druidic ‘onesie’ which was sea green covered with red ‘druidic’ symbols which he completed with his crescent moon staff, and was known to wear this combo to court. Price believed that religion was often used to enslave people, and despised “sanctimonious preachers”. Proclaiming himself Archdruid of Wales he regularly held druidic ceremonies on the site of the Rocking Stones, Pontypridd.

Eccentricity and even insanity ran in his family. In the 1820s and 30s would run naked around the hills of Pontypridd. He refused to wear socks, considering them to be unhygienic, and washed coins, fearing that they were a source of cross-contamination. Later in life, even out of his druidic robes, Price began to dress in a white tunic with green trousers, red waistcoat and a ‘shaman-style’ fox-skin headdress with the legs and tails hanging down over his shoulders and back. His hair was worn long in plaits and at the age of 83 he fathered a son Iesu Grist (Welsh for Jesus Christ) who died at 5 months old.

Price was heartbroken, but believing that burial polluted the earth, followed druidic practice & dressed in his robes, cremated the body on an open pyre in a field at Llantrisant. The locals were outraged as cremation, whilst not illegal was virtually unpractised in Britain at the time. They attacked Price and were only prevented from assaulting his wife by the pack of large dogs that Price kept at his home.

Price was arrested and charged. However, he was acquitted and this, together with the activities of the newly founded Cremation Society, led to the passing of the Cremation Act in 1902, making the burning of bodies legal in Britain. Price was now famous and ‘cashed in’ by designing & selling 300 medals at 3d each that depicted the ‘cosmic egg’ laid by the snake. In 1892 he erected a pole which was over sixty feet high, with a crescent moon symbol at its peak, atop the hill where his first son had been cremated.

Price’s final words, when he knew that he was near death on the night of 23 January 1893, were ‘Bring me a glass of champagne.’ He drank it & died shortly after. He was cremated on a pyre of two tons of coal. 20,000 people attended and the ceremony was overseen by his family, who were dressed in a mix of traditional Welsh and his own Druidic clothing.

(See: Dean Powell’s 2005 book: ‘The Eccentric life of William Price’)

Slide 8: Why Back to the Land started pre/post WW1; Change in Class Distinctions post WW1

In 1950, the artist and poet Wyndham Lewis looked back on what he called: ‘the insanity trough between two world wars’ but even in 1913, the writer Edward Thomas noted that ‘the modern, sad passion for nature’ was fundamentally a nostalgic yearning for traditional ways of being, for ordered structures of class and society, for a sense of wholeness and a ‘felt-life’ (cit. Holt, 2012).

‘Back to the land’ movements and yearnings for a ‘simple life’ did however, not necessarily imply a rejection of modern civilisation. The groups and individuals we will focus upon were not trying to return to a pre-industrial peasant society but attempting to introduce the best of ‘rural values’ (or at least a middle class concept of these) including light, health and tranquillity into the modern world.

Manifestations of this yearning for authenticity can be seen in the so called ‘Folk Revival’ which came into vogue at the end of the nineteenth century (and which occurred again in the 1970s). Organisations to protect the landscape were created such as the Commons Preservation Society (1865); the National Footpaths Preservation Society (1884) and the National Trust in 1895.

There was a flurry of initiatives both to save the countryside but also the individual trapped within the urban environment. The English Land Colonisation Society created 400 farming communities. Cooperatives were formed and derelict land and run-down farms were taken over; Arts and Crafts were revived and community increased. Later in the 1920s, the Dartington Trust promoted rural regeneration; The Garden City movement (see slides 21~23) focussed on town and garden design in urban areas; The Council for the Protection of Rural England and The Ramblers Association in the 1930 concentrated on town planning and the relationship to the countryside.

Slides 9 & 10: First Caravans & Gordon Stables (1837 to 1910)

So back to the Edwardians. One thing that most people know of this period is the polarisation of class and how one’s class (and income) dominated the extent to which one could challenge or break conventions of behaviour and social expectation. It is therefore no surprise to see that the earliest Edwardian pioneers of camping and outdoor pursuits (unlike the creative, artistic German pioneers) were upper middle class and/or aristocratic.

Later, the money for many of the new initiatives came predominantly from the wealthy and those with aristocratic connections or admirers, who (a degree of ‘Nimbysim’ maybe) were intent on ‘preserving the countryside, and controlling development.

If anything has an egalitarian image it is that of the caravan and the camping holiday but its roots lie elsewhere ~ not in the sturdy English peasant tradition but in the New World and in the lifestyle of the marginalised Roma gypsy. The ‘Vardo’ or gypsy caravan of popular imagination was actually only used by Romanys from around the 1850s, before that carts were used under which one slept or else ‘bender’ tents were made for sleeping. It is actually wandering showmen who have a longer tradition of ‘houses on wheels’.

Dickens describes Mrs Jarley’s wagon in ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ (1840) in which Mrs Jarley and her waxworks exhibition travel the country in a caravan: ‘…not a shabby, dingy, dusty cart but a smart little house upon wheels, with white dimity curtains festooning the windows, and window-shutters of green picked out with panels of a staring red.’

In the early years of the 20thc however, artists and some of the upper classes were drawn to the perceived romanticism of the vagabond and gypsy life and in the summer of 1907 Lady Arthur Grosvenor, sister-in-law to the Duke of Westminster, travelled through Oxfordshire disguised as a gypsy and calling herself Syeira Lee. It was part of the bohemian vogue for all things gypsy, with artists of the time such as Augustus John affecting the persona of the ‘Romany Rye’.

The real pioneer of so-called ‘land yachting’ was however, the ‘founding father of leisure caravanning’, retired Scottish naval surgeon & prolific children’s author Dr William Gordon Stables who in 1884 commissioned Bristol Wagon Works Co. to build a 30ft long, 2 ton, horse-drawn caravan which he named ‘The Wanderer’. It is important as it is the first time a caravan was used purely as a leisure vehicle.

Slide 11: Woodcraft/camping pioneer Thomas Hiram Holding

In 1859, 9 year old Thomas Hiram Holding learnt his woodcraft whilst travelling for 1200 miles across the American prairies with a wagon train. He invented the portable tent. In the 1890s, he and 4 of his friends embarked on what is believed to be the first bicycle camping trip which led to the book: ‘Cycle and Camp in Connemara’ (1898), the book led to the formation of Association of Cycle Campers in 1901.

Famous leaders of the Association included Captain Robert Falcon-Scott who later became known as ‘Scott of the Antarctic‘(1909-1912) & Sir Robert Baden-Powell who went on to form the scouting movement. The promotion of a healthy outdoor lifestyle greatly helped to popularise camping.

With grim predictability, the government started to worry that camping was being practised by the wrong ‘sort’ & the countryside could be overrun with tent carrying poor. In the 1930s it implemented laws to restrict camping including the banning of the sale of milk, bread, and butter on campsites and a minimum distance of 12ft from a pitch to a hedge.

Slides 12 & 13: Edward Carpenter (1844 to 1929)

By the early 20thc, the myriad environmental movements that arose were also responding to the economic depression which had hit the farming community after the prosperous years of the mid-19th century. After 1918, landowners and farmers saw falling prices, lower rents and untenanted farms. It is during this period that the Back to the Land movement with its various manifestations came into its own.

The first decades of the 20th century also saw public and government concern regarding restless workers, increasingly prone to strikes and union unrest & about the uneducated, unemployed and unemployable who were deemed morally and physically unfit. This was a period when suburbia was born, itself a proposed solution to the unhealthiness of the inner city yet which was soon portrayed by many writers as areas of stifling monotony and conformity.

A socialist revival occurred in the late nineteenth-century & quickly became associated with“crankish” beliefs, largely assisted by press mockery and derision from ‘real’ socialist writers such as George Orwell. As Michael Holroyd has written, at the time the socialist fraternity largely comprised: “agnostics, anarchists and atheists; dress and diet reformers; from economists, feminists, philanthropists, rationalists and spiritualists, all striving to destroy or replace Christianity”

Edward Carpenter, the so-called ‘patron saint of the dandelion-sitters’ and for the purposes of this talk, the first ‘New Age Celebrity’ exemplifies a perfect example of ‘the type’ and one that will reoccur in the Back to the land movements both in England and Germany: the mercurial, charismatic figure who attracts adherents and followers to his ideas and who, in turn, promulgates them to a wider audience. This then attracts the attention of writers.

It has been mooted that the readers of Orwell’ s Coming Up For Air (1939) would have recognised Carpenter as one the targets of his anti-crank satire in the book. In chapter 5, Orwell (in his guise of ‘George Bowling’ returning to his boyhood village) runs into a strange character…..

’There was something vaguely queer about his appearance. He was wearing shorts and sandals and one of those celanese shirts open at the neck, I noticed, but what really struck me was the look in his eye. He had very blue eyes that kind of twinkled at you from behind his spectacles. I could see that he was one of those old men who’ve never grown up. They’re always either health-food cranks or else they have something to do with the Boy Scouts — in either case they’re great ones for Nature and the open air….

‘They talk of their Garden Cities. But we call Upper Binfield the Woodland City — te-hee! Nature!’ He waved a hand at what was left of the trees. ‘The primeval forest brooding round us. Our young people grow up amid surroundings of natural beauty. We are nearly all of us enlightened people, of course. Would you credit that three-quarters of us up here are vegetarians? The local butchers don’t like us at all — te-hee! And some quite eminent people live here. ……..Professor Woad, the psychic research worker. Such a poetic character! He goes wandering out into the woods and the family can’t find him at mealtimes. He says he’s walking among the fairies. Do you believe in fairies? I admit — te-hee! — I am just a wee bit sceptical. But his photographs are most convincing.’

I began to wonder whether he was someone who’d escaped from Binfield House. But no, he was sane enough, after a fashion. I knew the type. Vegetarianism, simple life, poetry, nature-worship, roll in the dew before breakfast. I’d met a few of them years ago in Ealing.

However, Orwell could also be accused of being a little unkind. Carpenter, whilst advocating the ‘simplification of life’ was also a cultural and political activist remembered fondly in Sheffield and in Millthorpe , Derbyshire where he lived. Living openly as a gay man with his partner George Merrill, he spent his life campaigning for women’s suffrage, environmental protection, formation of trade unions and sexual emancipation.

Carpenter was a former curate and poet who wrote the poem, Towards Democracy. He promoted a so-called ‘spiritual socialism’ and a return to nature. As a result of a vision, he bought a smallholding at Millthorpe where he grew his own food. He was a vegetarian and an advocate of birth control and Eastern mysticism; he also wrote The Intermediate Sex, the first book generally available in Britain to shine a positive light on gay sex. He used to bathe naked at dawn with his manservant and lover, and his life was denounced as scandalous and immoral.

In his books ‘Towards Democracy’ (1883), ‘England’s Ideal’ (1887) and ‘Civilization, its Cause & Cure’ (1889) Marxist influences are apparent, but he later moved away from this to a more utopian socialism more akin to that of William Morris (Cachin, 1990). He denounced the idea of private property, exploitation of the working classes and promoting thea cooperative organisation of society and absolute freedom for the individual.

For both Carpenter and Morris, the role of Socialism was to put an end to the sense of alienation experienced by contemporary industrial, urban individuals so that they can experience freedom and fulfilment. For both men, socialism is regarded as a movement of liberation.

He founded the Sheffield Socialist Society in 1887 to promote the cause of ‘comradeship’ and the building of ‘moral communities’ outside of London, Carpenter opened the Commonwealth Café in Scotland Street, in a poor district of Sheffield; using the large room above for a meeting & lecture room.

Social gatherings, lectures, teas, entertainments were held in the Hall – wives and sisters of the “comrades” helped especially in the social work. Annie Besant, Charlotte Wilson, Kropotkin, Hyndman gave talks & free teas were distributed to the slum-children who dwelt in the neighbouring crofts and alleys. Carpenter believed that to build socialism one should simplify one’s personal life, have freedom of expression, do manual labour and makes one’s own goods and clothes.

Slide 14: Post WW1; Rise of suburbia & indeterminate class/roots of ecological thinking

1920S & 30S

The cataclysm that was WW1 marked the final disintegration of previously held moral and social outlooks that up until then had seemed unchanging and entrenched. It was even seen as the ‘end’ of western European civilisation, what James Webb called, ‘a flight from Reason’. Simultaneously in the early 1900s the relationship between town and country underwent a period of dramatic change, as the growth of suburbs and transport systems (the first electric tube line in 1890 & growing number of suburban train lines before 1914) allowed people to escape from London to the countryside. Class distinctions also began to change:

‘After 1918 there began to appear something that had never existed in England before: people of indeterminate social class…. The modern council house, with its bathroom and electric light, is smaller than the stockbroker’s villa, but it is recognizably the same kind of house, which the farm labourer’s cottage is not. A person who has grown up in a council housing estate is likely to be – indeed, visibly is – more middle class in outlook than a person who has grown up in a slum’

(Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius).

Slide 15: Caleb Saleeby & The Sunlight League (1924) [Eugenics]

This is where we come to Caleb Saleeby, the first of our more problematic characters and where vigilance is required regarding the application of 21st century P.C mores to emergent ideas of 90 years ago. He perfectly embodies the conundrum created by his ideas on race & eugenics that are now discredited and viewed with repugnance. Yet he also promoted women’s education and suffrage, the benefits of clean air and smoke abatement which were progressive and which we continue to believe in today.

There was a clearly developing belief in the connection between national economic efficiency and the good health of the populace. This went hand in hand with theories of eugenics, first propounded by the English Quaker Frances Galton in his book ‘Inquiries into Human Faculties and its Developments’ (1883).

He posited that ‘inadequate breeding’ and overbreeding on the part of the poor were ‘to blame’ for both ‘moral and physical’ disease. Physical and learning disabilities were linked to a range of social problems including crime, vagrancy, alcoholism, prostitution and unemployment.

Eugenicist ideas of selective breeding and even sterilization of ‘degenerates’ (approved of by Churchill) were mainstream at the time and championed by some of British socialism’s most celebrated names – Sidney and Beatrice Webb (the founders of the Fabian Society), Harold Laski, John Maynard Keynes, even the New Statesman and the Manchester Guardian. They hoped that a eugenic approach could build up the strong section of the population.

George Bernard Shaw wrote: ‘The only fundamental and possible socialism is the socialisation of the selective breeding of man.’ Bertrand Russell proposed that the state should issue colour-coded ‘procreation tickets’ to prevent the gene pool of the elite being diluted by inferior human beings. Those who decided to have children with holders of a different-coloured ticket would be punished with a heavy fine. HG Wells praised eugenics as the first step towards the elimination of ‘detrimental types and characteristics’ and the ‘fostering of desirable types’ instead.

None other than William Beveridge, the architect of the post-1945 welfare state, was highly active in the eugenics movement and said that “those men who through general defects are unable to fill such a whole place in industry are to be recognized as unemployable. They must become the acknowledged dependents of the State… but with complete and permanent loss of all citizen rights – including not only the franchise but civil freedom and fatherhood”.

Slide 16: The Sunlight League

There are very strong parallels with ideas on fresh air and sunlight that were prevalent in Germany at this time. Saleeby also promulgated the idea of naturism. If this lovely slide of Yew Tree Camp members enjoying a nice cup of tea does not illustrate the difference between the hearty German naturists and their more sedate English counterparts then nothing will……..

Slide 17: Naturism in England

…..It also was, and remains a minority activity in Britain unlike Germany where it is so mainstream that areas such as the ‘English Garden’ right in the centre of Munich is designated as a naturist zone.

Slide 18: Social Hygiene Movements: The New Health Society 1925

Founded by William Arbuthnot Lane, the NHS focussed on improving the diet of the nation. It believed that ‘civilisation’s curse’ could be cured by fresh air, sensible clothing and sunshine. It urged that more allotments be provided and that the urban poor should be resettled in the countryside.

However, this was to ensure that the masses would be ‘exposed to conditions of ‘”hardness” in which the fittest would excel & be ‘naturally selected’ thus cleansing society of ‘the discontents and unemployables who clog the wheels of progress, create disharmony & foster revolution’ (Belfrage 1926 cited in Carter, 2007).

Slides 19 & 20: Social Hygiene Movements: the Men’s Dress Reform Party (1929)

Strange to realise that adult men really did not wear shorts before the mid1920s. These formed a key health feature of the Men’s Dress Reform Party founded in 1929 by Alfred Jordan, an internationally renowned radiologist. He was famous for wearing shorts in his professional life, something that in this period was sufficiently unusual to generate press interest.

The MDRP was open to all classes of men, from the ‘working chap to the peer’s son’ and it was not a ‘crank or a faddist’ organisation but lobbied to end the tyranny of men’s dress away from heavy, hard to clean woollens and tweeds, sock suspenders, restrictive collars and in the case of heavier men – corsets.

Members included the artist Walter Sickert and lady members Barbara Cartland and the physician Stella Churchill. The ‘Tailor & Cutter’ journal however, thought it ‘odd’ for middle-aged and elderly men to be dressing like boys & the National Federation of Merchant Tailors labelled the |MDRP ‘ dress quacks’ who were ‘monkeying’ with men’s attire.

By the 1930s the movement held regular events: 1,000 people attended the ’31 rally at the London Suffolk St. galleries including H.G Wells & Alfred Jordan who appeared in a knee-length tunic, cape and sandals. Baden Powell (also an old friend of Caleb Saleeby) was interested in the movement & noted to them that his designs for Boy Scout uniforms largely met the movement’s ideals. The movement was also adroit at publicising itself through the media. Their 1937 Coronation design competition was one of the first events ever to be televised although only 50,000 people were able to receive the transmission.

Slide 21: ‘Three Magnet Diagram ~ Town & Country’

Slight jump back 30 years now to the end of the 19th century in order to take a broader look at theories on how to solve the physical blight of poor urban housing conditions.

Self-styled ‘freethinker’ Ebenezer Howard became very interested in social reform. In 1879 he joined the Zetetical Society, a philosophical and sociological debating group, which met weekly in the rooms of the Women’s Protective & Provident League in Covent Garden.

He met George Bernard Shaw & Sydney Webb there. Other influences were that of William Blake, William Morris, John Ruskin and Peter Kropotkin’s ‘Fields, Factories & Workshops’ In 1898 he laid out his utopian ideas for social reform through housing in ‘Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform’ by Sir Ebenezer Howard 1898 which was revised in 1902 as ‘Garden Cities of Tomorrow’ from which the diagrams come.

The’ ‘3 Magnets’ diagram outlines the positives and negatives of both country and town life in what must be one of the earliest examples of infographics (!). It is also notable for being an early indication of the suburbanisation of urban England that was to come within the next few decades.

Interesting that the ‘slumless city’ diagram includes in its utopian city ‘epileptic farms’, a ‘home for inebriates’, an ‘ insane asylum’, a ‘college for the blind’, ‘convalescent homes’ and a ‘home for waifs’.

Slides 22 & 23: Garden Cities (Letchworth Garden City 1904) & cranks in Letchworth cartoon.

On 10th June 1899, Howard established the Garden City Association (which still exists as the ‘Town & Country Planning’ charity) which organised lectures on “garden cities as a solution of the housing problem”.

In 1900, the Garden City Ltd was established with a share capital of £50,000 & in 1901 the conference held in Bournville led to Joseph Rowntree commissioning architects Raymond Unwin & Barry Parker to design houses for his workers in New Earswick which were heavily influenced by the ideas of Ruskin and Morris.

This was social reform through housing deliberately creating an environment which promoted health and happiness in its inhabitants and which laid the foundations for Letchworth & Welwyn later. Howard was the the M.D of the the Garden city Pioneer Co and through this he purchased 3,818 acrea in Letchworth for £155,587. He then employed Raymond Unwin & Barry Parker as the architects.

The concept was for idealised ‘cottages’ that combined a modernist ‘clean’ style of plastered walls and wooden floors. Each had a garden that was positioned to allow maximum sunlight. As always during this period, there were close ties and 3 way influences with developments in Germany. Howard knew the German architects Hermann Muthesius & Bruno Taut and they were influenced by him in their ‘humane design principles’ that resulted in Germany’s first garden city ‘Hellerau’ built in 1909.

It is clear from the illustration that this is a much more rural, spacious concept of suburbia than that we envisage from the term now. The inhabitants also have a very middle class air about them so these were in no way intended as slum clearance projects. It was apparent almost from its inception that Letchworth attracted a socialist inclined, middle class ‘simple lifers’ which in turn soon earned it a reputation for ‘crankishness’. An early resident described the ‘typical vegetarian Garden citizen,’ who wore sandals, read William Morris & Tolstoy, & kept 2 tortoises ‘which he polished periodically with the best Lucas oil.’

The vegetarians opened the Simple Life Hotel, which had a health-food shop and a food reform restaurant. A member of the Quaker Cadbury family started up an alcohol-free pub, the Skittles Inn, which offered hot chocolate & Cydrax, a non-intoxicating apple wine. Annie Besant, a theosophist and campaigner for birth control, opened the St. Christopher School—where the Independent Labour Party gathering was held—and which today still offers only vegetarian food. Only two of the originally intended garden cities were built: Letchworth and Welwyn Garden city.

Slide 23: A cartoon from a local newspaper showed day-trippers at a human zoo. “Daddy, I want to see them feed!” pleads a child. Signs for visitors include: “To the Long Nebbed Sandal Footed Raisin Shifters,” “This Way to the Non-Tox Pub,” and “To the Hairy-Headed Banana Munchers.” Writers soon followed, lampooning the puritan yet radical ‘type’ in their novels and articles.

Aldous Huxley’s short story, The Claxtons (1929) opens with the lines: ‘In their little house on the common, how beautifully the Claxtons lived, how spiritually! Even the cat was a vegetarian.’ Orwell (always cynically reliable in hatred of both Communisam and cranky socialism and in turn despised by both in return) lampoons the Letchwoth ‘type’ in The Road to Wigan Pier, where he writes:

One day this summer, I was riding through Letchworth when the bus stopped and two dreadful-looking old men got onto it. They were both about sixty, both very short, pink and chubby, and both hatless. … They were dressed in pistachio-coloured shirts and khaki-shorts into which their huge bottoms were crammed so tightly that you could study every dimple. Their appearance created a mild stir of horror on top of the bus. The man next to me … murmured ‘Socialists.’ …..He was probably right, the Independent Labour Party were holding their summer school in the town.

Slide 24: The ‘Problem’ of Socialist Cranks; Fascists in Loose Weave Cothing?

Later in ‘Wigan Pier’ (1937), Orwell derides one of the socialist cranks as a: “hangover from the William Morris period” who proposes to “level the working class ‘up’ (up to his own standard) by means of hygiene, fruit-juice, birth-control, poetry, etc.”

But tellingly he also cites why he feels that socialism is under threat from fascism identifying it as partly down to a ‘stupid handling’ of the class issue Notes that most socialists are of 3 types: either fiery young Communist types (‘youthful snob Bolshevik’) or meek lower middle class clerks then the ‘cranks’: ‘mingy little beasts with their sniffish middle class superiority’

George Bernard Shaw, who, as a vegetarian and wearer of unbleached and knitted natural wool, had a close relationship with crankery, also summed up the two different impulses in the socialism of the time: one was to ‘organise the docks,’he said, the other to: ‘sit among the dandelions.’

Orwell’s satire had a serious trajectory as concerns about the nature of Socialism had been causing concern for some time and clear divisions in its appeal were becoming apparent. This discourse regarding the nature of socialism can be seen as the ‘thrashing out’ (so to speak) of a new ideology. The debate had been ongoing since the earliest days of the social-democracy movement in the 1880s.

Orwell aimed to promote a popular (non-crankish), common-sense radical politics to face the growing threat of Fascism. In his view, cranks—along with “shock-headed Marxists chewing polysyllables”— were giving socialism a bad name. He also implied that they were only superficially committed to the socialist cause, and ultimately concerned more about their own moral purity than about the exploitation of the working class.

If one considers the dangers posed by the accompanying contemporary approval of views on racial purity and eugenics & notes again Bertrand Russell’s post-war view that these same crankish views had led straight to Auschwitz, one is presented with an interesting conundrum. The back to naturists regarded themselves and were regarded by many (if not all) as ‘socialists’ yet in the post 2nd world war period the perception of them retrospectively had swung sharply to the right. So were some of the people we are looking at this evening proto-fascists or pioneering socialists? The lines are and were often blurred and become more so over time, hence my caveats regarding lazy labelling.

Researchers appear to be conflicted regarding the back to nature movements of this period. Despite many proclaiming their ‘socialist’ roots as in the idea of communality and attempting to improve the lot of the working man, others note a strong right wing tendency. In the pre-war period, German ‘Blood and Soil’ and youth movements both influenced and were influenced by the English experience.

Anna Bramwell in her research on the topic (1985) notes that: ‘ecologists of the period were mostly conservative, monarchist and staunch traditionalists of the ‘green and pleasant land’ mythology which derived from the same traditions as the German Romantic Movement which in turn, came from immensely deep roots in German society’. Drawn from the Völkisch or ‘Volk’ in German culture, it refers to ethnicity from the “Blood” or ancestral descent and the homeland or ‘Soil’.

It places a vital importance on the notion of rural living and the place humans occupy in relation to Nature and their immediate environment. In retrospect it can be seen as ripe for appropriation into right-wing ‘eco-facism’ and in Germany for example, It was promoted during the rise of the Nazi Third Reich by Richard Walther Darré a Nazi party member, race theorist and eugenics advocate.

The key idea of the ‘Blood & Soil’ proponents was that the relationship to the environment over time becomes embedded in the consciousness of the dweller and vice versa – a concept promoted by for example, the German Artaman League, the same back-to-the-land movement of which Himmler was a member. Indeed, in 1953, the philosopher Bertrand Russell identified the 1920s Blood & Soil back to nature ideas of amongst others D.H Lawrence as views that ‘led straight to Auschwitz’.

Russell and indeed ourselves are viewing the period with the benefit of hindsight, so I would argue that when viewing the English experience, one should be cautious. Cultural ties between Germany and England were extremely close during the 19th century and these survived into the 1930s despite the Great War. The first decades of the 20th century saw a degree of polarisation in political outlook re. left and right wing views – views that changed dramatically with the onset of WW2. As can also be seen, ideas that were indeed appropriated by the far right have also been handed down to us today and are happily mainstream so whether one regards some of the individuals we will look at now as heroes or villains is one that must remain moot.

**As The Telegraph noted recently regarding the Cecil Rhodes statue controversy: ‘Intelligent minds are capable of understanding that while history informs the present, it does not necessarily define it or imprison it.’

Slide 25: Intro to Woodcrafters

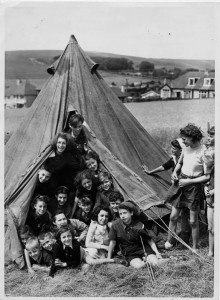

Increased leisure time led to a craze for the open air & ‘wholesomeness’ during the 1920s and 30s. Membership of the Clarion Cycling Club reached a peak in the mid-1930s, and city dwellers took to youth hostelling and rambling. “Freedom to roam” was a Socialist issue & mass hiking a political act, often with a touch of nature mysticism.

Camping was part of this tendency before the idea of camping out became tainted by associations with fascism & militarism. Baden Powell had allowed the military authorities to support his Boy Scout movement during the war. This alienated many of his more internationalist, socialist and pacifist Scoutmasters (including as we shall see later John Hargrave who founded the Kibbo Kift).

There were fears that the Scouts were effectively being turned into a military cadet group so breakaway movements began that were more influenced by Socialist, Quaker, pacifist and ruralist ideas. The Woodcraft & other ruralist non-military groups sprung out of this rebellion and included These secular, and non-military groupings included the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry (1916), Kibbo Kift Kindred (1920), Girth Fyrd (Anglo Saxon for Peace Army, and the Woodcraft Folk (1925).

Researchers and writers investigating these breakaway movements all agree that the English woodcraft movement in all its manifestations has had, an outsize impact upon progressive and ecological thought despite the often low numbers of their membership. Many of their views and beliefs survive to this day and this is why we will now take a closer look at one or two pioneers and proponents of the Woodcraft Movement.

Slide 26: The Ecologists: John Muir (1838 to 1914)

Pioneering work, often by British born individuals was undertaken in the USA and this awareness of an unspoilt landscape and contact with indigenous peoples who transmitted their insights into working with, rather than against nature, were in turn disseminated through writing, reaching Britain and influencing the early Boy Scout movement and English Woodcrafters.

One of the earliest of these individuals was the the Scottish born ‘father of American conservation’ John Muir. His strict Scottish Calvinist family moved to a homestead in Wisconsin in 1849 (when he was 11) in an area heavily forested and populated by indigenous Indians.

In his early 20s he invented agricultural machines that gave him a route out of the farm and to university where he studied geology, botany and the writings of Transcendentalists such as Emerson and Thoreau. After suffering an eye injury he decided to give up work to devote himself to studying the ‘meaning’ of nature.

He undertook a 1,000 mile journey from Indiana to the Gulf of Mexico and kept a journal where he recorded his view that encountering nature was the route to sensing divine beauty and the harmony of creation. In 1868 he went north to the Sierra Nevada Mountains where he spent several winters in Yosemite Valley working as a shepherd and where he met Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1871. It was Emerson who provided Muir with contacts to publishers.

From the 1870s Muir started to campaign for public ownership in order to preserve wilderness areas writing articles such as ‘God’s First Temples: How Shall We preserve our Forests?’ which appeared in the February 4, 1876, issue of the Sacramento Record-Union in order to do so. In 1881, he lobbied Congress unsuccessfully to establish a national park on the model of Yellowstone in the King’s River area in the southern Sierra. In 1888 he campaigned for preservation of the Mt. Shasta area in northern California as a public park.

In 1889, Muir was approached by Robert Underwood Johnson, the associate editor of the Century magazine, which was at that time the most influential monthly review of literature in the United States. Johnson asked Muir to write two articles for Century advocating creation of a national park at Yosemite and similar enclaves elsewhere in the West. Muir’s two articles appeared in the magazine in 1890, along with illustrations.

The articles reached at least 200,000 readers. In September 1890, Congress passed and President Benjamin Harrison signed a bill creating Yosemite National Park, the first park specifically intended to protect wilderness. Muir and Johnson banded together with faculty members from the University of California and the recently created Stanford University, as well as members of the business and professional communities, to form an association that would help to further the goals systematically. In June 1892, twenty-seven men formed the Sierra Club with Muir as first President (an office he held for the next twenty-two years until his death).

Years later Theodore Roosevelt read Muir’s journals by chance and was so impressed that he arranged to meet Muir in 1903 spending 3 days walking and discussing with him. President Roosevelt went on to place the Yosemite Valley under federal protection & to implement 5 national parks, 55 national bird sanctuaries & 150 national forests. In Britain, Muir’s name lives on in the John Muir Trust which campaigns to protect wild places and the John Muir Award which has introduced 150,000 people in Britain to his philosophy of conservation.

**Note: early 19thc U.S and Canadian woodsmen (many of Scots or French extraction) paved the way for the woodcraft skills & veneration of nature that were exported back to the UK. As seen in the earlier slides however, it was technological developments pioneered in England around 1865 such as lightweight tents and sleeping bags weighing no more than 7lb in total that revolutionised long range trekking and camping – a fact acknowledged by American woodcrafters and survivalists.

Slides 27 & 28 .Woodcraft Pioneers; ‘Black Wolf’ Ernest Seton (1860 to 1946)

Seton (‘the Chief’) AKA “Black Wolf” was an award winning wildlife illustrator and naturalist who was also a storyteller and lecturer, a bestselling author of animal stories, expert with Native American sign language and early supporter of the political, cultural and spiritual rights of so-called ‘First Peoples’. He was born in Durham of Scottish ancestry but the family emigrated to Canada in 1866.

Seton had a talent for art & won the Gold Medal for art before he was 18. At 19 returned to England & won a 7 year Royal Academy scholarship but did not complete it due to ill health arising from poor food and living conditions. A cousin urged him to return to Canada before he died which he did in order to study natural history in Toronto then rejoining his brothers at their Carberry homestead in 1881.

He spent weeks exploring the wilderness studying the flora and fauna and was considered odd and lazy by the locals (a ‘crank’ in other words….). He began to write articles and visited New York in 1883 where he met up with many naturalists, ornithologists and writers. From then until the late 1880s he commuted between Carberry, Toronto and New York becoming an established wildlife artist, and was given a contract in 1885 by the Century Company to do 1000 mammal drawings for the Century Dictionary.

In the early 1890s he went to Paris to study art & undertook the research for his first book, The Art Anatomy of Animals, published in England. It was there that met Mark Twain for the first time. His painting ‘The Sleeping Wolf’ hung in the Paris Salon in 1891 and ‘Triumph of the Wolves’ was exhibited at the First World Fair in Chicago in 1893

Due to eye problems he left Paris and travelled to New Mexico Fitz-Randolph’s ranch, and hunted wolves. The story of “Lobo” came from this hunt & was first published in Scribner’s Magazine, and then with other stories in book form as Wild Animals I have Known. In the early 90s he was appointed Official Naturalist to the Government of Manitoba, a title he held until his death in 1946.

He married for the first time in 1896, to Grace Gallatin, a wealthy socialite, who was also a pioneer traveller, founder of a women’s writers club, a suffragette, & a leading fundraiser for War Bonds in WWI. Their only child, a daughter, Ann, was born in 1904 and died 1990. She is better known as the popular writer of historical novels, Anya Seton.

Start of Woodcraft by Seton

Forerunners to the Boy Scouts, the first Woodcraft Tribe was established at Seton’s Windygoul estate at Cos Cob, Connecticut in 1902. Seton’s property had been vandalized by a group of boys from the local school. After he had to repaint his gate a number of times, he went to the school, and invited the boys to the property for a weekend, rather than prosecuting them. He sat down with them and told them stories of Native Americans and nature.

The unique feature of his program was that the boys elected their own leaders, a Chief, a Second Chief, a Keeper of the Tally and a keeper of the wampum. This was the beginning of his Woodcraft Indians, which later became the Woodcraft League of America. Seton wrote a series of articles for Lady’s Home Journal in 1902 that were later published as the Birch Bark Rolls and the Book of Woodcraft. At the urging of his friend Rudyard Kipling, Seton published Two Little Savages as a novel, rather than a dictionary of Woodcraft.

Like John Hargrave of the Kibbo Kift & ErnestWestlake of the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry after him, Ernest Thompson Seton drew on the thinking of writers like G. Stanley Hall, for example using his ideas around ‘recapitulation’ as a rationale for camping. Stanley Hall propagated the idea of ‘instinct psychology’ and the idea of boyish savagery. Yet instead of seeing ‘savagery’ as merely a rung on the ladder to civilization the way Hall did, Seton saw virtue in in for its own sake, citing American Indians as the ‘noble’ proponents of this natural lifestyle in tune with its environment. In 1915 he proposed a Red Lodge for men to learn the spirit of Indian religion.

The approach he proposed used camping out and various ceremonies, games and awards. Significantly, Seton did not follow the usual path of character builders by ensuing the preaching of conventional morality. Crucially, he made all offices elective and looked strongly to the associational life of the group

He visited Britain in 1904 and 1906 to promote his work around woodcraft. In 1906 he was a guest of the Duke of Bedford, and was looking for people interested in this sort of an outdoor organization. Through the Duke, he was introduced to Baden Powell who was impressed by him. Seton gave Baden Powell a copy of the Birch Bark Roll, and they corresponded from that point forward. In 1908, Baden Powell stated that he was implementing his scheme for Scouting, based largely on Seton’s theories. Baden Powell incorporated many of Seton’s ideas into his book Scouting for Boys, to the extent that Seton was later to claim that Baden-Powell had stolen ‘many of Scouting’s essential ideas from him’ (Rosenthal 1986: 71).

Like John Hargrave and Lesley Paul after him, Seton believed that Baden-Powell’s use of ‘Be Prepared’ ‘was a prescription for war, a commitment that in his view the entire Scout organization, in its activities, rhetoric and principles of unwavering obedience to Scout officers, shared’ (op. cit.). In short he believed that Baden-Powell had betrayed the spirit of woodcraft. His ideas also inspired splinter groups from the Scouts such as Ernest Westlake’s Order of Woodcraft Chivalry (formed in 1916) and John Hargrave’s Kibbo Kift Kindred (founded in 1920). The Woodcraft League of America grew to some 5000 members – but ‘organizational laxness and perhaps the eccentricity of Seton’s ideas barred sustained growth’ (Macleod 1989: 239).

Seton established a program he called ‘brownies’ in 1921 for age 6 through 11 girls and boys, based on his earlier book Woodland Tales that served as the origin of the Brownies in the Girl Scouts of America. Seton provided materials and a framework for their new organization for girls. In 1915 Seton founded the Woodcraft League of America as a co-educational program open to children between ages “4 and 94″. There were many local Woodcraft groups in the USA during the early 20thc & many survive today around the world inspired by Seton’s 1912 book The Book of Woodcraft

In 1910 Seton was chairman of the founding committee of Boy Scouts of America. He wrote the first handbook (including B-P’s Scouting material) and served as Chief Scout from 1910 until 1915. Seton did not like the military aspects of Scouting, and Scouting did not like the Native American emphasis of Seton. With the outbreak of WW1 Seton resigned from Scouting.

Slide 29: Woodcraft Pioneers; Archie ‘Grey Owl’ Belaney (1888 to 1938)

Belaney was one of Canada’s first conservationists and is said to have saved the Canadian beaver from extinction. Born in Hastings, he was fascinated by stories about Native American Indians and travelled to Canada at the age of 17 to live with a group of Ojibwas Indians in northern Ontario and then marrying a girl from the tribe. He learnt the language and how to trap and canoe.

He was already hiding his true identity, telling visiting traders and trappers that he was ‘Grey Owl’ – half Scot and Apache. After WW1 enlistment as a sniper in the Canadian army, he was wounded and returned to Hastings where he married a local woman, then abandoned her to return to Canada for further travelling.

He spent 4 years studying under the Native American Ne-Ganikabo becoming skilled in survival techniques and married again to an Iroquois woman called Anahareo in 1825. It was she who persuaded him to take some orphaned beavers home after he had hunted the mother. He stopped trapping to begin writing and conservation work after this incident, warning of the dangers to the beaver population posed by the logging and fur industries.

His first book which is part memoir and partly ecology was The Men of the Last Frontier (1931) and it turned him into a celebrity. His past life in Hastings was not mentioned at all & he introduces himself as a ‘half-breed Indian born near the Rio-Grande’. The fame of his books led to Grey Owl being invited to carry out lecture tours of Canada, England and the United States in the 1930s and as Clive Webb, professor of modern American history at the University of Sussex states, Belaney was the ‘first celebrity conservationist’.

He became an animal caretaker at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba and made his first film for the National Parks Service. He then moved to Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan and established a beaver colony in the park. A spokeswoman from the park said the conservationist wrote most of his books in Beaver Lodge. He was obsessive about his conservation work and began drinking heavily. His wife Anahareo left him after which he married a French-Canadian woman called Yvonne Perrier, who accompanied him on a tour which saw him appear before the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace. In 1938 he died of pneumonia at the age of 49.

After his death his first wife came forward and revealed he was an Englishman. It was hugely damaging to his reputation as a conservationist. Native Americans resented his ethnic impersonation and his books were withdrawn in many instances or re-issued using his real name. Don Smith, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Calgary subsequently stated: ‘His personal life was a mess but he had insight, he had vision. This man had a message. Everybody’s green now. He was green when there was nothing to it. His message was ‘you belong to nature, it does not belong to you’.

Richard Attenborough had attended a Grey Owl lecture as a boy in Leicester in the 1930s and in 1999 made a film about Belaney starring Pierce Brosnan in the title role and Hastings Museum and Art Gallery has had a permanent exhibition dedicated to him since 2007.

Slide 29: Ernest Westlake; The Order of Woodcraft Chivalry

Ernest Westlake was a geologist, pioneering anthropologist and Quaker. From the late 1870s he was engaged on geological research and fieldwork, excavating coastal & inland areas all over Britain focussing on artesian wells, chalk formations and tertiary deposits. His notebooks also record his interest in spiritualism, hypnotism, dowsing & psychical phenomena.

In 1882 he became one of the early member of the Society for Psychical Research (found the same year). After being widowed he undertook further geological research in Tasmania & France and in 1910 returned to England, buying a small estate in the New Forest and later the one next door called ‘Sandy Balls’ where he focussed on his interest in naturism and conservation.

He aimed to open a Forest School where nature could be experienced at first hand through camping and woodcraft activities, a Quaker alternative to the perceived militarism of Baden Powell’s Boy Scouts. In 1915 several leading members of Scouting in the Cambridge area also broke away from the perceived militarism of the movement, joined Westlake and the ‘Order of Woodcraft Chivalry’ was founded in 1916 as a counterpart to this.

It was designed for boys, girls and adults following a more pacifist, inclusive Quaker-based trajectory. Westlake was heavily influenced and advised by Ernest Thompson Seton and his 1902 Woodcraft Indian group. Seton’s ‘Birch Bark Roll’ books were used to guide and structure the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry into Lodges, controlled by regional councils.

A ‘lodge’ comprised 3 or more ‘Elves (5-8 years old); ‘Woodlings’ (8-12 year olds); ‘Trackers’ (12-15 years olf); ‘Pathfinders’ (15-18 years old); ‘Waywardens’ (18-25); ‘Wayfarers’ (25-60) & ‘’Witana’ (60 & over). Each lodge had a Lodge Chief for administgrative purposes and a Keeper of the Sacred Fire, responsible for the ceremonial & spiritual wellbeing of the lodge.

A ‘Sun Lodge’ was used to initiate ‘higher order’ members into the 3 degrees of mysteries & spiritual aspects of nature and woodcraft. Westlake always felt that the OWC was based on Christian-Quaker beliefs and claimed: ‘One must be a good pagan before one can be a good Christian’.

Like Ernest Seton and John Hargrave and his KibboKift movement, the Westlakes were interested in the American child psychiatrist G. Stanley Hall’s theory regarding the psychology of adolescent development which led to a system of youth training based on the belief that adolescents have to live through or ‘recapitulate’ all the stages of human development before theycan appreciate the present stage of evolution. – this was the reason for the focus on the tribal and primitive in both the OWC and the Kibbo Kift later.

The idea was to give the child an opportunity to ‘recapitulate’ the ancestral and racial experience by passing through early stages of evolution in the form of colourful ritual, ceremonial, and woodcraft training, containing elements from both the Boy Scouts and Seton’s woodcraft precursor.

It is mooted that the famous Wiccan Gerald Gardner (also based in the New Forest) based and adopted his Gardnerian Wicca movement (founded 1950s) but this has also been disputed. Westlake died in 1922 but his son & heir Aubrey, although working to create a co-educational Forest School, left the active role of ‘British Chief’ of the Order to Henry ‘Dion’ Byngham who abandoned any pretence of Christian-Quaker precepts for all-out paganism, being a worshipper of Pan & Artemis.

Byngham advocated worship of the phallus as a way to venerate the life-force & Woodcraft Chivalry as: “a leaping and dancing movement of modern Bacchae through the land……symbolically the order should be proud to regard its self as the erect penis of the social of which it is a part.”

He was an advocate of nudity in ritual and once danced naked with his girlfriend in honour of the “sun god” at Sandy Balls, Westlake’s estate. Byngham also edited the Woodcraft Chivalry’s journal , a hitherto Quaker-based children’s publication The Pinecone. His first editorial made it explicit that the pine cone of the title represented not only the pine cones strewn about Sandy Balls but also the head of a penis. The magazine contained a verse play by Victor Neuberg who also introduced Byngham to the ideas of the occultist Aleister Crowley.

In one article he wrote that: “life springs out of the star-tissued womb of Nature as the virile son of the All-Mother”. The Pinecone’s fourth issue featured a nude Byngham on the cover playing the panpipes while his girlfriend danced in a Grecian tunic above him, with one breast exposed. All this brought Byngham into strife with many of the Christian members of the Order, which was primarily aimed at children and had, by its pacifist stance, particularly appealed to Quaker families as an alternative to Scouting. In 1924 Byngham was replaced as editor and in 1925 he was suspended from the Council of Chiefs, mainly due to the fact that he and his girlfriend had posted nude in a Sussex field for press photographs to promote the idea of naturism (Hutton, 1999).

Byngham’s notoriety had led to a drop in membership from 1,200 in 1926 to 400 by 1930 when the Quaker ‘Society of Friends’ withdrew their support for the Order. In 1934 Aubrey Westlaker resigned from the OWC so the order could not use the Sandy Balls estate any longer. The OWC and the Forest School Camps exist to this day holding national & international meets. The grandson of Ernest Westlaker allows the Order to hold their ‘back to nature’ camps and annual ‘Folkmoot’ ceremonies at the national headquarters of Aubrey’s estate at Sandy Balls Holiday Park, Godshill, near Fordingbridge, in the New Forest. They teach permaculture and a respect for nature to its members and students.

Slides 31 to 33: Rolf Gardiner (Eco Facist)

‘The old urge and spirit of adventure which came to young manhood with the Tudors and which colonised the Empire is exhausted and can kindle our hearts no more.’ (Gardiner)

Kinder critics have called Gardiner a ‘rural revivalist’ and he exemplifies the individual who can be viewed either in a negative light as an authoritarian eco-fascist colluding with contemporary German ideology or as a new-age pioneer with prescient views on the preservation of the countryside and man’s relationship with it. Zimmerman (2004) identifies the type as often gravitating towards the rich history of the Völkisch and sometimes towards the New Order proposed by National Socialism or towards the other extreme of Communism/Socialism.

As he puts it, the back to nature movement was: ‘both a product of the times and a trigger which seemed to draw out the latent extremism waiting to leak from otherwise natural and healthy principles.’ If one is not convinced by this one just has to see how the ideas were appropriated by the German far right. Hitler’s Mein Kampf states: ‘When people attempt to rebel against the iron logic of nature, they come into conflict with the very same principles to which they owe their existence as human beings. Their actions against nature must lead to their own downfall.’

Firmly upper middle-class, Gardiner became involved in folk dancing while a pupil at Bedales School, and joined a dance side while a student at Cambridge. His mother was half Austrian Jewish & G therefore had a long standing interest in German culture. He joined a work camp in Germany in 1927 & led his young male camper comrades in a naked sun dance at six in the morning. By 1930 he was hosting work camps for Kings’ College students at his uncle’s farm in Dorset with singing around the campfire.

He farmed at Springhead near Fontmell Magna in Dorset from 1927, promoting organic farming, and rural traditions – what he called ‘ecology in action’. By 1938 Springhead had a well-established yearly round of festivals, meetings, summer schools and work camps, all with music and dance. The summer schools were not, according to Gardiner:

…merely artistic training and enjoyment: it was to realise the point at which life enters and becomes form; it was to experiment with a form of social and facultive discipline of which polyphonic music was a perpetual symbol.’

May Day or ‘Spring Festival’ was a particular celebration, with festoons, garlands, a dancing procession and village sports. Harvest was another, with a feast in the barn. Gardiner thought:

Each estate should organise festivals and occasions of social rejoicing. We require engineers of social affection as well as engineers of economic and technical efficiency.

The German Oswald Spengler’s 1918 ‘Decline of the West’ (Untergang des Abendlandes) was a huge influence on Gardiner’s ideas. Spengler believed that any civilization is a super-organism with a limited lifespan. His book ‘Man & Technics’ (1931) warned of the dangers posed to culture by technology and industrialism. Gardiner too believed that a new Dark Ages was descending on the West but also drew on English anti-urbanism & anti-capitalism in the vein of William Morris, Carlyle & Ruskin.

He made contact with Hargrave’s Kibbo Kift group in his 2nd year at Cambridge asking Hargrave whether he could advertise his magazine for Cambridge undergraduates called ‘Youth’ in the Kift’s magazine ‘the Nomad’. By 1924 he was using the name (& London Office) of Kibbo Kift to spread his own ideas (and magazine ‘Youth’).

According to a female member, Gardiner brought ‘something of what the Wandervogel were doing [to the KibboKift]….breaking of the taboo against discussing sex, throwing off your clothes in camp and of discussing anyone else’s religion’. G never became an actual member of KK as he heard that Hargrave was dictatorial. When G became a roving ambassador for KK in Europe during 1924, Hargrave insisted that G wear uniform when undertaking Kibbo business. & gave G the name ‘Rolf the Ranger’

Hargrave also put G in touch with youth groups in Germany. Later Gardiner joined the ‘English Mistery’ group. It was the brainchild of an obscure writer called William Sanderson, a disgruntled Freemason, and took its name from his 1930 book: ‘That Which Was Lost: A Treatise on Freemasonry and the English Mistery’. Apparently, Sanderson had particular views about leadership and society. Basically, he believed in the promotion of a landowning elite and the ‘rule of the best’ – in other words, an ‘aristocracy’ – in the true meaning of that word.

The Mistery was led by Gerard Wallop, 9th Earl of Portsmouth & Viscount Lymington. After a split in the English Mistery in 1936, the ‘English Array’ was formed with a more overtly pro-Nazi agenda which aligned it with Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists. The central tenet of both the Mistry and Array was the essential link between ‘pure’ English blood and the soil, feudalism, distrust finance (anti-Semitism played its part here), hatred of socialism and faith in the inherited wisdom & benevolence of the aristocracy.

The English Array became a much more rounded and active group than the English Mistery, promoting a ‘back-to-the-land’ ruralism, organic food and farming methods and an early interest in the environment. Lymington organised the movement’s cadres into ‘musters’, which were led by ‘marshalls’, and engaged in rural-based activities and training camps with practical work in the countryside and frequent lectures on the movement’s principles and aims.

English Array was also one of the first modern political groups to use the red rose and the Cross of St George as public symbols. It also published a quarterly magazine in order to influence public opinion & amongst its members was Lord Rothermere, who famously backed Mosley and his British Union of Fascists (BUF) in the early thirties via his Daily Mail newspaper.

Gardiner saw Britains future as lying in a ‘Northern Federation’ with the states around Germany and the Baltic Sea – ones that shared ‘frontiers of race & culture’.From the late 1920s he publicly advocated policies to counter what he saw as the “impoverishment” of the national racial stock, and from 1933 published anti-Semitic views, initially in German. However, he expressly rejected overtures made to him by members of Mosley’s party, which at the time was gaining ground in rural areas in response to the effects of the depression and tithe collection on farming. He also despised ‘excesses of jingoism’ and ‘museum patriotisms’

His colleagues referred to him as a man of the ‘conservative revolution’, a German term that described intellectuals who had given up on liberal democracy and who sought a new, more dynamic form of leadership as a form of rebellion against the levelling effects of mass society (Jefferies & Tyldesley, 2011).

When the full extent of the Nazi programme became known Gardiner also modified his idiosyncratic interpretations of folk ritual. After the Battle of Britain in 1940 he distanced himself from Nazism during a radio broadcast claiming that he had supported German ruralists’ long before their ideas had been appropriated by the Nazis.

In 1941 Lymington helped to establish the ‘Kinship in Husbandry’ group with Gardiner a precursor to the Soil Association (founded in 1946) of whom the Prince of Wales is patron. The ‘Kinship’ original group of 12 met in rooms at Merton College and had some influence on agricultural policy, specifically self-sufficiency and later it influenced the trajectory of the ‘Rural Reconstruction Association’ founded in 1935 by Montague Fordham, and the ‘Biodynamic Association’. Gardiner never stopped believing in the curse of technology on the human spirit. After WW2 he stated that:

….our over-complicated civilisation is becoming more mobile and unrooted , and the sum result is an artificiality which sooner or later results in serious breakdowns even to the point of cataclysm , such as seems to be overwhelming us now. (Gardiner)

Slides 34 & 35: Woodcraft Folk: Lesley Paul (1906 to 1985)

We will now take a look at two key woodcraft groups of the 20s and 30s, one of which still exists i.e. Lesley Paul’s ‘Woodcraft Folk’ who started as a breakaway group from John Hargarve’s Kibbo Kift (see slides 36-58)

The irony has since been noted by critics that both founders criticised the Scout movement for being rooted in the political aura of the Edwardians yet they themselves directly reflected the ‘modish, experimental, or nonconformist educational and political ideas of the 1920s’. The Kibbo Kift is especially singled out for this and its demise identified as its restricted appeal to the ‘essentially conservative parents of working-class children’.

However the Woodcraft Folk do still exist today as the oldest socialist Youth Movement in the country. If Gardiner led the ‘conservative revolution’ then Lesley Paul represents the Socialist Front.

18 year old Lesley Paul was part of a more overtly socialist orientated co-operative splinter group of the Kift called the ‘Brockleything’. They challenged Hargrave’s leadership when he tried to override decisions they had made. Leslie Paul was appointed ‘Head Man’ of the new group at this meeting. Hargraves refused to accept the new group & wanted to throw Paul out of the K.Kift.

The real ‘issue’ (said Paul) is that the new group was Socialist in nature which did not appeal to Hargrave ‘who was moving more and more to the right’ (Paul, 23:31 ‘History of Woodcraft’ YouTube: https://youtu.be/VJv3nU145UI)

Paul thinks Hargrave made the ‘excuse’ that Paul was underage (16-17) and therefore couldn’t lead a group but that he used this just to get rid of the left-wing group altogether. The row rumbled on for around 2 years by which time Paul was 18 or 19. Paul thinks the debate turned into one around democracy i.e. whether the members themselves could decide the trajectory of the movement.

The co-operative branches withdrew from the Kift in 1925 and Paul led the new youth organisation which aimed to pioneer a new style of woodcraft-based youth group with leaders who were directly linked with the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and the co-operative movement nationally (like Paul’s successor Basil Rawson).

The first folkmoot was held on 19th December 1925 in the cooperative hall at Rye Lane, Peckham, resulting in the formal foundation of the Woodcraft Folk (WF) or Federation of Co-operative Woodcraft Fellowship. The WF was again was based on Stanley Hall’s ‘recapitulation theory, Thompson Seton’s Red Indian woodcraft lore, Rudolf Steiner’s educational ideas, and socialist internationalism.

Paul did however criticise Seton’s Woodcraft Indians claiming that: ‘……their idealism kept them independent: their independence kept them small’ which could equally have applied to both his and Hargrave’s groups. Overall, the WF programme between the two world wars combined: ‘recapitulation theory, pacifism, internationalism, socialism, and the eugenic ideal, all propounded in Paul’s writings.

In The Folk Trail (1929), camp life is portrayed as an antidote to the evils of urban-industrial society as is the pursuit of arts and crafts; tribal organisation and training; and the teaching of world history and evolution.

They promoted internationalism & in the 1930s were in touch with the German Bünde, the Austrian Rote Falken (Red Falcons), and the Czech Sokols. They also took part in raising money for children evacuated during the Spanish civil war; visited socialist youth groups in Europe; held international camps; participated in demonstrations, such as Peace Pledge Union and May Day rallies; and helped the No More War movement to counter Empire Day celebrations.

Suburban membership expanded from the 1960s onwards, reaching a peak of triple the previous figure by the 1970s when its ecological, progressive, and gender policies became mainstream. While such values remain broadly relevant, child and teen membership is now around 4,500: organised into Woodchips (under 6), Elfins (6 to 9), Pioneers (10 to 12), Venturers (13 to 15), and District Fellows (16 to 20), together with 2,500 adult members. Of the 300 active paying groups (there are now year-on-year financial losses) about two thirds are in London and the south-east.

By avoiding the romantic and exotic excesses of the KKK and the middleclass, obscurantist, sect-like image of the OWC, the left-wing and initially more working-class WF grew in numbers until it had an active child (not until 1963 did they recruit older teens) and adult membership of 4,500 by the late 1930s. As an independent auxiliary of the co-operative education movement, the WF is nowadays co-educational, often vegetarian, and now largely middle-class.

Slides 36 to 40: The Kibbo-Kift: John Hargrave (1894 to 1982)

Quaker John Gordon Hargrave (aka ‘White Fox’ – 1884-1982) had a 70 year working life that included periods as an artist, illustrator, cartoonist, copywriter, Boy Scout Commissioner, lexicographer, inventor, psychic healer and author (he published the ‘Lone Scout’ book at 19 and wrote five bestselling novels). H left school at 12, was entirely self-taught and interestingly later banned books and pens in his movement.

In 1909, he joined the Baden-Powell’s Boy Scouts, soon being made Commissioner for Woodcraft and Camping. Rising up the Scout hierarchy, Hargrave wrote his first book Lonecraft for solitary scouts, promoting the idea of ‘standing on one’s own feet’ in 1913. He then produced a series of scouting and woodcraft books for C. Arthur Pearson Ltd, who offered him a position of staff artist in 1914, his first salaried job.

His experiences as an RAMC sergeant in WW1 embedded his views regarding the failure of ‘our great disorganised civilisation’ which he set out in his book ‘the Great War Brings it Home’ (1919). It included his ideas for outdoor education & open air camps & even for a programme of yoga which he called a ‘programme of regeneration’.

In 1920 he founded the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift ~ the name being archaic Kentish dialect for ‘proof of great strength’. The idea was that a body of men & women, drawn aprt from the mass would act as a catalyst on a corrupt & directionless society & lead it back to health & wealth’ (Elwell-Sutton, 1979).

His displeasure with what he perceived as the militarism of the Scouts led to his being formally asked to leave the movement in 1921 He soon objected to the militaristic & nationalistic tendencies of the Scouts & in 1921 was formally asked to leave after submitting provocative articles to the Scouting magazine.

His KK was based on the woodcraft principles of Ernest Seton that had also been key to the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry and also the early Scout programme. Unlike the other 2 groups however, the Kibbo Kift was to be not just a youth organisation but was to involve all ages and (unusually for the time) both sexes. By its 2nd meeting in 1921 there were 200 members mainly from London & the Home counties.

Key to the KK philosophy was the idea of global peace and the regeneration of urban man through an open-air life, physical training, learning hand crafts and the reintroduction of ritual into modern life. Hargrave’s lofty ideal was to create the ‘human instrument’ through physical & mental discipline that would in turn forge a new World Civilisation not enslaved to concepts like class, race or nation states.

The KK leant more towards a 19thc Romantic Transcendental attitude to the countryside that included the concept of ‘communing’ with the natural world by harnessing the physical exertion of strenuous walking. Hargrave felt that walking restored, ‘the natural proportions of our perceptions, reconnecting us with both the physical world and the moral order inherent in it’. What is so endearingly English about the KK however, and what I feel forms a direct line to the English festival scene today is their love of dressing up and a sense of ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’ for the ordinary man and woman. The KK ‘agrarian futurists’ central activity of hiking and camping was refined and elevated to the level of a spiritual exercise.