Ragged Schools History: The Children; The Poorest of the Poor

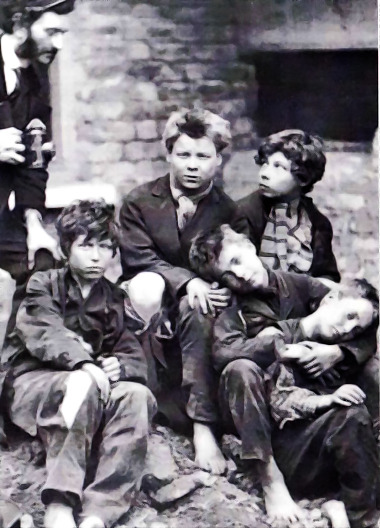

The ragged schools aimed at providing schooling for the very poorest children and succeeded in attracting them into the schools in large numbers. Those who went out into the streets to recruit children for the schools and those who taught them were often horrified by what they saw.

Writing in 1884 about the children that it had helped over the last forty years, the Ragged School Union described them as “shoeless, capless, and shirtless, sometimes with shreds of old and ill-fitting and grotesque-looking clothing, scarcely sufficient to cover their nakedness, and wholly insufficient to protect them from the winter’s cold.”29 Given the pupils who attended the schools, it is easy to understand why they were called ‘ragged schools’.

This lack of clothing caused much suffering. In 1847, Thomas Guthrie wrote about one boy who had “neither shoes nor stockings; his naked feet are red, swollen, cracked, ulcerated with the cold.”30 Alexander Maclagan, who wrote a book of Ragged School Rhymes in 1871, made plain the misery that many ragged children endured. In his poem ‘The Lost Found’ he urged readers to remember that:

“When o’er the face of nature sweeps

The wintry winds so wild

When ye are warmly clad, O think

Upon the Ragged Child.”31

Some of the children were not only in rags but were dirty and verminous. When the Coombe Ragged School in Dublin opened in 1853, the teachers found that few of the children had “washed face and hands” and that some wore “filthy rags”.32 Such was the condition of the children who attended the schools that measures were often taken to make them more presentable. Quintin Hogg, who started a ragged school near Charing Cross in London in 1865, found that the “boys used to come into the house in an indescribable condition, so that it was absolutely necessary to shave their heads and scrub them from head to fool.”33

A similar course of action was taken at the Edinburgh Ragged School, with time being allowed each morning for the children to wash themselves which they did with “Eastern precision.”34 Other ragged schools followed this example and provided washing facilities for their pupils. In 1 843, Charles Dickens wrote to S. R. Starey, treasurer of the Field Lane Ragged School in Holborn, offering to pay for a “washing-place, a large trough or sink” for the pupils.35 The children were also encouraged to come to school clean and tidy although it was acknowledged that, given the conditions that some children lived in, this was not always possible.

Some schools, as well as providing washing facilities, went further and provided boots and clothing for their pupils. Where there was a danger that parents might pawn or sell these gifts, boots were stamped with the school’s name, receipts were issued or the amount of clothing given out to any one child was kept small so as not to tempt the parents.

Although the ragged schools were able to distribute clothing where necessary, there was little they could do to prevent those diseases which were a result of the children’s poverty. During a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School and Night Refuge for the Homeless in London in 1859, the writer was appalled by what he found:

“Here come four meagre little forms; they are mere children, all under the age of fourteen, all orphans, destitute, and living upon the streets, without a home or friend in the wide world. One has a pair of tattered canvas trousers and the remains of a grown man’s fustian jacket hanging about his little limbs. Dirt and sores disfigure his body, his eyes are swollen, his face is puffed and fevered-looking; for, though spokesman of the party, he can scarcely draw his breath from inflammation of the lungs.”36

Where possible, and especially during epidemics, home visits were made and food given to the pupils and their families. During the cholera outbreak in 1866, teachers of one ragged school worked as a relief agency, caring for the sick, sending some to hospital and distributing gifts of meat, rice, bread, beef tea, flannel, calico, port wine, brandy and arrowroot.37

Such gifts undoubtedly helped comfort those in distress but those connected with the ragged schools were helpless to improve the terrible conditions that they saw around them. Given the poor standard of living experienced by many of the ragged school children, the death rate amongst them was often high. In 1880, Sarah Davies wrote of her experience of this, noting that “Very many of the little children who come to the Coombe Ragged School die early.”38 Those connected with other ragged schools would have had similar experiences.

Family and Home

As well as commenting on the general appearance of the ragged school children, observers also took note of where they lived. Their accommodation included some of the worst types of housing, the slums and rookeries that were found in every city or large town. Writing about its forty years’ experience, the Ragged School Union recorded that:

“Many of the rookeries in which the poor were herded together were wretched almost beyond description — their so-called homes were dilapidated, dark, dirty, damp, unprovided even with the commonest decencies of civilised life, they had become the haunts of every kind of repulsiveness, the breeding places of fever and contagion. ”39

When home visits were made, the teachers were often shocked by the poverty that they found. During a measles outbreak in Edinburgh, it was discovered that of the fifty-five homes of pupils visited, only three had “even the vestige of a bed.” In the other fifty-two homes, the children slept on the bare floorboards without bed-clothes of any kind.40

Yet these children were more fortunate than those who had no homes at all and who were forced to find shelter where they could. If a child managed to earn enough money during the day, a night’s accommodation could be found at a lodging house.

Although offering protection from the cold and the wet and possibly providing some food, lodging houses were universally condemned as the dens of thieves and prostitutes and were blamed for corrupting the young by bringing them into contact with “degraded and brutalised persons”.41

For those children who could not afford the cost of a night at a lodging house, there was no alternative but to sleep under railway arches, in doorways, on roofs, under market stalls or in disused wagons. Numerous children were forced to seek shelter in this way. When Thomas Barnardo recounted his experience of this to a group of men, including Lord Shaftesbury, who were connected with the ragged schools, they doubted that the situation was as bad as he claimed.

To prove his point, Barnardo took them to an area in London full “of old crates, and empty barrels which were piled together, covered with a huge tarpaulin” which was sheltering seventy-three boys for the night. Shaftesbury was so shocked by this sight that he took all the children for a meal at a nearby inn.42 It was the plight of children like these that led the ragged schools to set up homes or refuges for those pupils who were homeless.

For many ragged school children, family life could be hard. There were those children who were without one or both parents, those whose parents were unemployed or else could only secure occasional work or those whose parents turned to crime to support themselves or to drink to forget their problems. Some ragged schools made a point of collecting information about the family circumstances of their pupils. The Stockport Ragged School recorded the following details about the parents of those children who attended between 1854 and 1861:

“29 mothers charwomen

10 children had both parents dead

29 parents were professedly factory workers but many of them were drunkards and profligates

20 parents were professed beggars

16 parents had no fixed employment

3 parents were pedlars

1 parent was a prostitute

2 parents were soldiers

1 parent was in jail

1 parent had been transported

1 parent had absconded.”

At the Stockport Ragged School, the number of children missing either one or both parents was high. Out of 135 pupils in 1873, thirty-one were orphans and sixty had only one parent. This picture would have been similar for many of the other ragged schools.43

For some ragged school children, a combination of poor housing conditions and parental problems meant that home life could be miserable. George Acorn who attended several ragged schools in London between the ages of three and twelve, recalled an unhappy childhood. Apart from the beatings that he suffered from his drunken father, what made a vivid impression on him was the way that his parents fought with each other:

“Cups and saucers were picked up from the table and thrown at each other; then, struggling violently, they would throw themselves to the floor and fight, scratching and punching like wild beasts; until the noise brought the landlady up from downstairs to separate them . . .”44 For such children, school may have been a welcome relief from family life and poor living conditions.

Making a Living

Those children who were only able to attend the ragged schools in the evenings or on Sundays did so because necessity forced them to work during the week. All kinds of work, usually the worst and most badly paid, was available to those children who had to find jobs to support themselves and their families. The range of tasks undertaken was enormous but mainly consisted what was known as ‘casual’ labour.

In 1851, the children who attended the Liverpool ragged schools were described as “thieves, vagrants, chip and grit sellers, rope workers, butchers’ boys, apprentices, boys of a precarious means of living, the lowest class of labourers’ children, factory workers, dockers’ children.”45

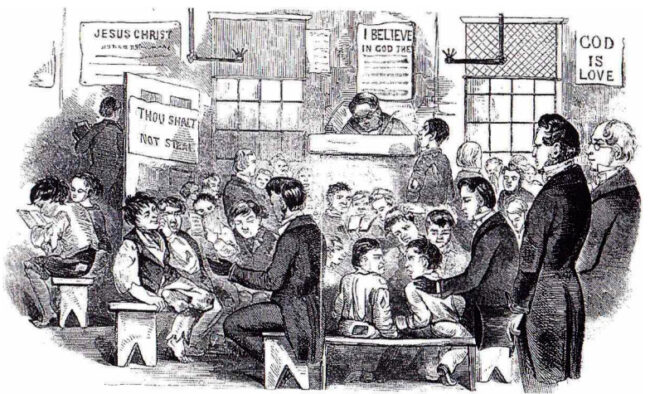

School, near Charing

Cross, cl849

Working conditions were often poor, and sometimes dangerous. Where machinery was involved there was always the risk of injury or death whilst some industrial processes were detrimental to the children’s health. In the textile industries, for example, the fibres from the materials got into the air and lungs causing respiratory diseases while in the pottery industry the lead used in the glazes could lead to skin problems and death from poisoning.

Almost every occupation that children undertook carried its attendant discomforts and hazards. Even where children found employment in jobs offering better working conditions, the hours could be long and the work tiring. Mrs Layton who, as a girl, attended a ragged school in Bethnal Green in London two evenings a week, recalled working twelve hours a day as a domestic servant when she was only ten years old.46

Some of the ragged school children worked at home alongside their parents, involved in various forms of needlework or else making matchboxes, brushes, cheap toys or other such products. Such work was notoriously badly paid and the hours were long. Even as late as 1910 when the last London ragged school closed,47 eight year old Ted Harrison, his mother and his brother were only paid twopence a gross for making artificial flowers in their London home.48 Such work was referred to as ‘sweated’ labour in recognition of its poor conditions and low wages.

Other children found work on the streets, selling newspapers, hawking wares, sweeping streets and running errands. Again this work did not normally pay very well and the hours could be long as the children tried to make sufficient money to feed themselves. Unlike other forms of work, the children of the streets, or ‘street arabs’ as they were called, were exposed to every sort of weather in order to make a living. On a wet November day in 1877, Thomas Barnardo came across a young girl selling newspapers in London:

“She had no boots or stockings on, and no fragment of hat or bonnet covered the wild hair that hung in wet, tangled masses about her neck. Her thin dress, showing great rents here and there, was as wet as though she and it had been dipped bodily in a pond and then allowed to stand up and drip.”49 For those who were unable to find work, the only means of surviving was to turn to begging or petty crime. The pupils of the Jersey Ragged School, which opened in 1847, were described as “half-clothed, ill-fed street arabs who went nowhere to school, begged off passers-by, or prowled about the piers, pilfering and stealing coals, apples or potatoes from carts carrying them to and from the vessels in the harbour.”50

Thomas Barnardo evoked a similar picture of London when he wrote in 1877 of the “half-famished, half-naked children who prowl about alleys and railway arches, fruit markets, and the river foreshore.”51 Incidents of crime and begging amongst ragged school children were numerous. In a speech to the House of Commons on 6 June 1848, Lord Shaftesbury said that out of an attendance of 1,600 ragged school pupils, 162 had been in prison sometime during their short lives and 253 lived wholly by begging.52

By catching these children early, the ragged schools hoped that they could keep them from crime, begging and poorly paid casual work by offering them some educational skills and by dissuading them from obtaining money through these means.

Little Savages

Although in retrospect many ragged schools were able to record the good behaviour and progress of their pupils, there were occasions when the ragged school children proved difficult, if not impossible, to teach. The Heyrod Street Ragged School in Manchester recorded in its Annual Report for 1862 that the children were:

“ . . . thoroughly educated in all the sharpness and deceitfulness of vice, and in all the common slang terms and foul expressions which are used in ordinary conversation among this class of society. They take especial delight in the rudeness of their behaviour and the neglect of their persons. Tobacco chewing and smoking are by no means uncommon among the very young.”53

Where a teacher was new or not yet established, there could be additional problems. When Henry Adams began teaching in 1852 at the Whitechapel Road Ragged School in London, he found that, knowing very little himself, the children made “game of him.” He was however determined not to give up. The more he taught and the more he learnt in the process, the greater his teaching skills became. As he improved as a teacher, the respect his pupils had for him grew and they modified their behaviour accordingly.54

Quintin Hogg, who taught in London near Charing Cross, also found that any weaknesses were quickly exploited. Too ill himself to teach one night, he allowed an enthusiastic female teacher to take his place. Later that same evening, he was called from his bed by one of his pupils. When he reached the school, he found the whole place in “an uproar, the gas-fittings had been wrenched off and used as batons by the boys for striking the police, while the rest of the boys were pelting them with slates.”

With the appearance of Hogg, who had no trouble controlling his pupils, order was quickly restored.55 Such problems normally occurred at the evening schools where the pupils tended to be older and rougher. At one stage, because of the number of complaints it had received about the behaviour of the children, the Ragged School Union looked into the cost of providing a policeman for each school. The cost of 3s 6d a day was prohibitive, and so the scheme was abandoned.56

It was not only the boys who caused problems. Quintin Hogg found in his experience of teaching in London that “The girls were almost as entire little savages as the boys; they usually came in turning Catherine wheels, whilst one arrived with a policeman in hot pursuit, and led him an exciting chase over the forms and desks.”57 The Ragged School Children’s Magazine also complained in 185 1 that the girls’ behaviour was less than it should be, writing that: “What a pity it is that girls — who ought always to be kind, and gentle and quiet — are so often quarrelling when in school! ”58

Despite these experiences and others like them, there were those children who were keen to learn and who made an effort to behave. Quintin Hogg noticed how, over time, his pupils changed: “In 1 864 the boys were ragged, unkempt, ignorant, without even the desire to rise; in four years’ time those same boys had become orderly, decent in dress, and behaviour.”59

Charles Dickens remarked on a similar improvement in the children of the Field Lane Ragged School in Holborn, whom he had a chance to compare over a period of years. His first visit witnessed the school in complete mayhem:

“. . . the teachers knew little of their office; the pupils, with an evil sharpness found them out, got the belter of them, derided them, made blasphemous answers to the Scriptural questions, sang, fought, danced, robbed each other . . . seemed possessed by a legion of devils. The place was stormed and carried over and over again; the lights were blown out, the books strewn in the gutters . . . Some two years since I found it quiet and orderly, full, lighted with gas, well-whitewashed, numerously attended and thoroughly established.”60

Obviously not all ragged school children made this kind of improvement. There were those who did not stay long enough to gain from the ragged schools and there were those who simply could not be ‘reclaimed’ from their old lifestyle. Yet for some, the change must have been both dramatic and beneficial.

Bibliography of References

29. RSU, p.10.

30. Thomas Guthrie, A Plea for Ragged Schools (1847), p.9.

3 1. Alexander Maclagan, Ragged School Rhymes (1871), p. 16.

32. Davies, p. 12.

33. Ethel Wood, A History of the Polytechnic (1965), pp.38-9.

34. Thomas Guthrie, Seed-Time and Harvest of Ragged Schools (1860), p. 163.

35. Williamson, p.31.

36. The Result of a Visit to the Field Lane Ragged School and Night Refuge for (he Homeless (1859), p.10.

37. Montague, p.285.

38. Davies, p.53. During the nineteenth century one child out of every two died before its fifth birthday.

39. RSU, p.3.

40. Guthrie, Seed, p. 159.

41. Thomas Barnardo, Rescued for Life (1883), p.4. Barnardo ran a series on common lodging houses in his magazine, Night and Day between 1877 and 1878. In the issue for January 1877, he wrote that in the previous year, 1241 registered lodging houses in London had accommodated approximately 27,000 people (p.3).

42. Williamson, p.67. Similarly, one night in May 1848, the Field Lane Missionary found “seventeen wretched, homeless, friendless creatures” sheltering under some nearby railway arches. Clarke, p. 1 64.

43. Webster, pp.287-8.

44. George Acorn, One of the Multitude (1911),p.2.

45. Webster, p. 154.

46. Mrs Layton, ‘Memories of Seventy Years’ in Margaret Llewelyn Davies (ed), Life As We Have Known It (1977), p.20.

47. Ridge, p.20.

48. S. Humphries, J. Mack and R. Perks, A Century of Childhood (1 988), pp. 16-8.

49. Thomas Barnardo, A City Waif (1883), p.6.

50. Montague, p.223.

51. Night and Day, 15 January 1877, p.3.

52. RSU, p.15.

53. Quoted in Webster, p. 138.

54. Chainpreys, pp.34-5.

55. Montague, p.290.

56. Webster, p.68.

57. Wood, p.41.

58. Ragged School Children’s Magazine, March 1851.

59. Wood, pp.39-40.

60. Bloomer, p. 101.

The above research was produced by Claire Seymour first produced in the book ‘Ragged Schools, Ragged Children’ for the Ragged School Museum which on the back page had the following:

Started in the late eighteenth century the ragged schools aimed to provide an education for the poorest and most destitute children in the country. Such was the need for the ragged schools that, in 1844, the Ragged School Union was formed to encourage the establishment of new schools. As a result, numerous schools throughout the country were founded.

These schools gave thousands of children not only a basic education but much more besides, from food and shelter, to arranging clubs, treats and outings for them. Claire Seymour, who researches social history and is a member of the Ragged School Museum Trust, recounts the history of the ragged schools and tells the story of the children who attended them.

She describes the kind of lives that the children led, their often unruly behaviour and shows how the ragged schools helped them and their families. Also examined are some of the many individuals, such as Dr Thomas Barnardo, whose determination and dedication enabled the ragged schools to succeed.