Working Classness: Class as a Topology of Finance and Status

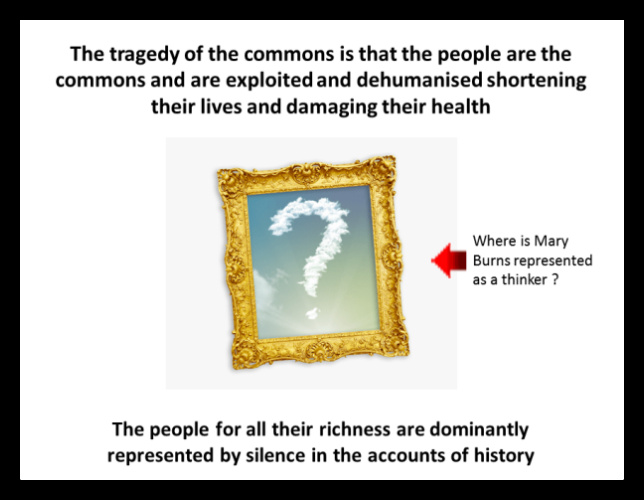

In this work I am attempting to make sense of the world, not just from my own perspective but to find a formulation which offers a means of understanding the sense other people make from their relative positions in shifting and changing cultural landscapes. Class as a term gets used a lot in Britain but the erosion of language has meant that the meaningfulness of language has become soft in places. When this happens we have no choice but to use qualifiers in order to retain the usefulness of the words we are utilising.

Important to me is to establish an articulated meaning of the language that I am using so that I can construct sufficiently complex cultural and sociological analyses using the explanatory power which emerges from the internal logic of the words. This is not to fix the language and insist upon a singular ‘true’ definition of what ‘working class’ means, but instead I am choosing to anchor to a particular reading of it that allows me to orient my arguments in relational ways.

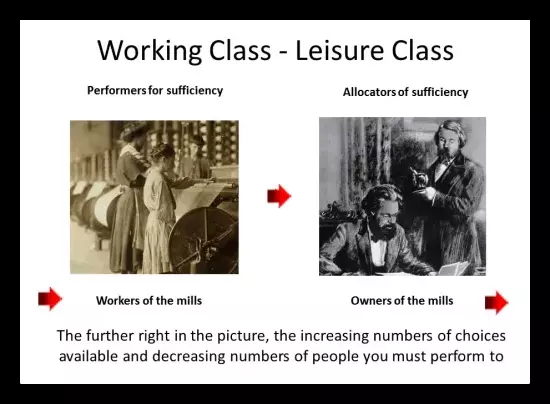

I am going to be laying out the groundwork of ‘class’ in terms of a topology of finance and a related status deriving from that finance associated with opportunity and agency in the world. I will be using class as a simple category that expresses where an individual is in relation to resources – distant or close. In example, if we were to look at a picture of a beach in a seaside town, we could create certain classes around where people are in the picture below. In this example a class of people might be formed from those who are seen in the water and a class of people who are on the sand.

We might as reasonably create different ‘classes’ of people from the photograph (if we can distinguish them) using criteria such as height or age or sex or whether they wear a hat. The important thing in the use of the term ‘class’ is that the operational distinctions are made explicit to give it falsifiable explanatory power. It is in this way that I will be exploring ‘class’ in the sense of ‘grouping’ as a linguistic device that associates an individual with certain characteristics that make up a category. Class results as a result of a process of classification.

In the paper I will be describing the common characteristics found in the lives of people who are situated in the category of working – more so and less so. In context I will be examining how factors intersect and coalesce to inform where an individual resides in a topology of finance and status as well as notionalising how verticality can inform situations which, at face value, seem to contravene the definition but are in fact expressions of the driving patterning principles at work.

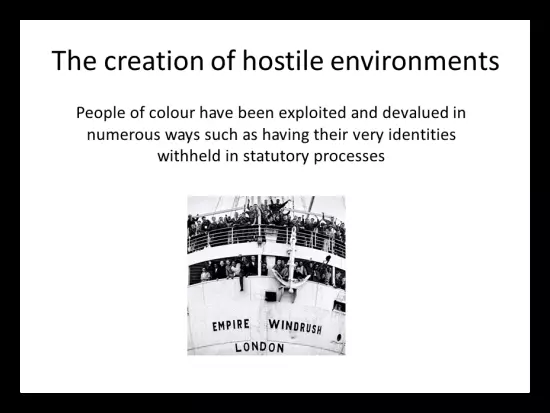

Informing factors include social groups excluded and displaced from the socio-economic institutions and opportunities of society and who are, as a result, denied their voices in the body politic (social groups also known as the subaltern). Typical examples include intersecting realities of gender, race, sexuality. This work necessarily also involves understanding class as how people who find themselves in categories are organised in hierarchies that are recreated by participants in socialised norms.

The name subaltern derives from the work of Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. The original Italian usage, ‘subalterno’ translates as ‘subordinate’. The term carries in it class analysis with Gramsci originally referring to peasants and the lower working classes and over time it has expanded in use to designate the general attribute of subordination. Here for the clarity of the language I shall be using the language of finance, opportunity, subordinate and class.

“The Subaltern studies collective was founded in 1982 under the intellectual and editorial auspices of Ranajit Guha. Its name derives from the terminology of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, who used the name ‘subaltern’ to interrogate the Marxist focus on the urban proletariat and to emphasise the role of culture and the question of popular consciousness (Gopal 2004: 141; see also Brennan 2001). In its original Italian usage, ‘subalterno’ roughly translates as ‘subordinate’ or ‘dependant’ (Arnold 2000: 30).

While the term suggests class analysis – originally referring to peasants and the lower working classes – its definition was expanded by the Subaltern historians to designate ‘the general attribute of subordination … whether this is expressed in terms of class, caste, age, gender, and office or in any other way’ (Guha 1982a: vii).

Concerned with the histories, agency and politics of social groups that have been excluded, elided, dominated and oppressed by both colonial and post-colonial state formations, Subaltern studies contests the notion that a resurgent national culture ever works as a panacea capable of resolving issues of poverty, sexism, patriarchy, racism and so on.”

[Lehner, S. (2014). Subaltern ethics in contemporary Scottish and Irish literature: Tracing counter-histories. Palgrave Macmillan. Page 8]

The notion of verticality aims to add dimension and complexity to intersectional accounts offering insights of how differing scenarios can amount to changed status despite the backdrop of macro-generalisations. An example might be how someone sharing characteristics of the dominant cultural group, may in specific circumstances experience disadvantage which recreates them as an outgroup. Verticality as an idea can then offer useful accounts of situational effects and I would argue is essential to negotiate the divisive nature of identity politics to maintain a fix on universal human rights and justice.

This sociological formulation places people within a topology of finance and status and necessarily includes details of how individuals are recognised (or not), how they are valued (or not), and how they are humanized and dehumanized in relation to others in the hierarchy which forms of the intersecting realities of each persons life circumstances.

Drawing this together, I am searching for a meaningful account of what makes some individuals predominantly of the ‘working’ category of people, what distinguishes people moving up through the hierarchy of status designated as finance, and which also holds true for extreme outgroups who find themselves in anomalous positions. It is a tentative expression of a phenomenological sociology of people in relation to resources and the distinctions that afford meaningful separations of groupings as expressed by their status which is intra-actionally linked with the resources they have access to.

Table of Contents

Intersecting Silences and Historical Production

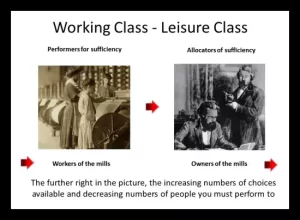

In the story of Mary Burns and Fredrich Engels, we can understand that Mary Burns had several intersecting realities informing her position in society and the topology of finance and status. Mary was poor and as such was of the working class having little choice but to perform for others higher up in the hierarchy.

Mary was part of the Irish diaspora displaced from their lands and cultures to work in the industrial mills and factories of Manchester and as such was facing the cultural dehumanization of racism; Mary was female caught in a long and insufficiently questioned history of dehumanization and exploitation we know as sexism.

These cultural realities intersect in the socio-economic reality of her being poor; a double signifier itself signaling the least valued and most devalued grouping/s of society. A valid question is to ask is what is represented in the thinking of Marx and Engels (the Siamese writers) equally of her thinking ? She was caught in the silence of rich, white, male dominance rhetoric about the world and as a consequence we are left with nearly no trace of her.

The critical framework of intersectionality was developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Crenshaw, 1989) to resolve the problematic consequences of the tendency to treat race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis. Her work set forth this analysis to contrast the multi-dimensionality of Black women’s experience with the common single-axis analysis that distorts these experiences.

“I have chosen this title as a point of departure in my efforts to develop a Black feminist criticism because it sets forth a problematic consequence of the tendency to treat race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis.’ In this talk, I want to examine how this tendency is perpetuated by a single-axis framework that is dominant in antidiscrimination law and that is also reflected in feminist theory and antiracist politics.

I will center Black women in this analysis in order to contrast the multidimensionality of Black women’s experience with the single-axis analysis that distorts these experiences. Not only will this juxtaposition reveal how Black women are theoretically erased, it will also illustrate how this framework imports its own theoretical limitations that undermine efforts to broaden feminist and antiracist analyses.

With Black women as the starting point, it becomes more apparent how dominant conceptions of discrimination condition us to think about subordination as disadvantage occurring along a single categorical axis. I want to suggest further that this single-axis framework erases Black women in the conceptualization, identification and remediation of race and sex discrimination by limiting inquiry to the experiences of otherwise-privileged members of the group.

Crenshaw, K., (1989) “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf&sei-redir=1

After a study of the sparse fragments left which do refer to Mary Burns I am suggesting that she was at the center of a series of intersecting disadvantages which served to silence her, effectively erasing her from history almost entirely; I am also suggesting that she was an important thinker in relation to Fredrich Engels as well as Karl Marx whose influence has been erased from history. I am drawing on Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theoretical framework of intersectionality to illustrate how the life of Mary Burns was “theoretically erased” and Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s theoretical framework of power and the production of history (Trouillot, 2015, Page 25) to illustrate how she was silenced.

“The search for the nature of history has led us to deny ambiguity and either to demarcate precisely and at all times the dividing line between historical process and historical knowledge or to conflate at all times historical process and historical narrative. Thus between the mechanically ‘realist’ and naively ‘constructivist’ extremes, there is the more serious task of determining not what history is—a hopeless goal if phrased in essentialist terms—but how history works.

For what history is changes with time and place or, better said, history reveals itself only through the production of specific narratives. What matters most are the process and conditions of production of such narratives. Only a focus on that process can uncover the ways in which the two sides of historicity intertwine in a particular context. Only through that overlap can we discover the differential exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and silences others.

Tracking power requires a richer view of historical production than most theorists acknowledge. We cannot exclude in advance any of the actors who participate in the production of history or any of the sites where that production may occur. Next to professional historians we discover artisans of different kinds, unpaid or unrecognized field laborers who augment, deflect, or reorganize the work of the professionals as politicians, students, fiction writers, filmmakers, and participating members of the public.

In so doing, we gain a more complex view of academic history itself, since we do not consider professional historians the sole participants in its production. This more comprehensive view expands the chronological boundaries of the production process.”

Trouillot M.-R. & Carby H. V. (2015). Silencing the past : power and the production of history. Beacon Press.

Crenshaw developed the apparatus of intersectionality to reunify the fragmented elements of individuals to represent the real lives of people which had been “theoretically erased” through the kind of categorical handling of singular aspects which dominates attention thus limiting the further advancement of feminist and antiracist (and other) analyses. Devon Carbado makes the point that limiting understandings and applications of intersectionality theory is to artificially constrain its generative, normative, and analytical capacity (Carbado, 2013).

Carbado points out that the intersectionality framework has moved into and built bridges across a significant number of disciplines and areas of focus. It offers a useful tool of reunifying experience and analysing in social processes the “multiple axes of difference” such as classism, homophobia, religious prejudice, xenophobia, nativism, ageism, ableism, and sexism.

“It is part of a larger ideological scene in which Blackness is permitted to play no racial role in anchoring claims for social justice. But even assuming that one thinks that it is problematic for intersectional analyses to focus on Black women or on race and gender, the claim that the theory is inapplicable to other social categories is theoretically unnecessary, descriptively inaccurate, and easily falsifiable. Scholars have mobilized intersectionality to engage multiple axes of difference—class, sexual orientation, nation, citizenship, immigration status, disability, and religion (not just race and gender).

And they have employed the theory to analyze a range of complex social processes—classism, homophobia, xenophobia, nativism, ageism, ableism, and Islamophobia (not just anti-Black racism and sexism). Seemingly, the genesis of intersectionality in Black feminist theory limits the ability of some scholars both to imagine the potential domains to which intersectionality might travel and to see the theory in places in which it is already doing work.3

The next three criticisms of intersectionality (that the theory is identitarian, static, and invested in subjects) are curious given the theory’s genesis in law and critical race theory. Intersectionality reflects a commitment neither to subjects nor to identities per se but, rather, to marking and mapping the production and contingency of both. Nor is the theory an effort to identify, in the abstract, an exhaustive list of intersectional social categories and to add them up to determine—once and for all—the different intersectional configurations those categories can form.

Part of what Crenshaw sought to do in “Demarginalizing the Intersection” was to illustrate the constitutive and ideologically contingent role law plays in creating legible and illegible juridical subjects and identities. Her effort in this respect is part of a broader intellectual tradition in critical race theory to demonstrate how the law constructs (and describes preexisting) social categories.”

Carbado, D. W., (2019), ‘Colorblind Intersectionality’, In Crenshaw, K., In Harris, L. C., In HoSang, D., & In Lipsitz, G. (2019). Seeing race again: Countering colorblindness across the disciplines. Page 200

In stating “It is not necessary to believe that a political consensus to focus on the lives of the most disadvantaged will happen tomorrow in order to recenter discrimination discourse at the intersection” Crenshaw relocated agency in the life of the authentic individual away from reifying political institutions and practices that dislocate us from knowledge which aids us in making sense of the world (Crenshaw, 1989).

The human cultures which we find ourselves attempting to make sense of have certain imagined realities associated with them; they are imbued with the fairytales we tell us about our selves and the worlds we create as ordered and orderly, deliberated and deliberate. Trouillot states an important aspect of how human culture comes to be configured in certain ways: “Effective silencing does not require a conspiracy, not even a political consensus. Its roots are structural” (Trouillot, 2015; Page 106).

“I am quite willing to concede that the conscious political motives are not the same. Indeed again, that is part of my point. Effective silencing does not require a conspiracy, not even a political consensus. Its roots are structural. Beyond a stated—and most often sincere—political generosity, best described in U.S. parlance within a liberal continuum, the narrative structures of Western historiography have not broken with the ontological order of the Renaissance. This exercise of power is much more important than the alleged conservative or liberal adherence of the historians involved.”

Trouillot M.-R. & Carby H. V. (2015). Silencing the past : power and the production of history. Beacon Press. Page 106

This helps unsettle the problematic notions of conscious and orchestrated cultures; sometimes it is the very language we use which structures the actions of people in hypnagogic ways. For example, a man need only feel they treat a woman as an equal to believe it whilst drawing on a sentiment to charter actions which renders agency from the woman in the name of ‘protecting the weak’.

Sociologically speaking we need to include develop analyses of self organising ideas (like memes) within our behaviour if we are to get beyond simplistic accounts of why the world is the way we find it. Understanding how cognitive dissonance and the tacit payload implicit of an idea are key aspects to decoding the invisible structures at work that shape social or anti-social outcomes.

The Missing Story of Mary Burns

My overall focus in this writing is to articulate the tragedy which befalls the people who, at one point, could draw sufficiency from commons but who have been coercively dispossessed from those indigenous means; as a result, this population – made precarious – must perform in a hierarchy of permissions and allowances for access to sufficiency. Mary Burns is one of uncounted, innumerable examples who have been wiped from memory and representation in similar fashions.

To contextualise the focus of our study here, Burns was born into a family which was a part of the Irish diaspora leaving Ireland due to the authoritarian rule of Britain. The Irish people had fallen victim to chronic and dire forms of racism, including overt epistemicide, perpetrated by the British government banning all forms of education for the Catholic Irish population. Amongst other things, the Cromwellian regime had initially imposed a ban on education for the Irish people which was carried forward under the Penal Code which was introduced during the reign of William III.

It is worth highlighting that we can hardly imagine the civic circumstances of a woman in the period we are examining, let alone a single woman, a woman of non-British origin or a woman without independent financial means. Mary Burns was a woman living in a country and time which barely recognised women beyond a cult of domesticity. She lived in a time when women were not allowed to own property, they were not allowed to vote, and they had scant representation in law bar being regarded as the property of a man (the laws of Coverture).

The dominant reality which she lived with was the fact that she was financially poor. This I argue is significant not just a result of being of outsider cultures pushed to the margins of society, not just as a result of being of a gender systematically dispossessed over the long arc of history, but also because being poor is promoted as a mark of deviance in and of itself. In this way financial poverty brings itself about because it is used to distinguish people who have transgressed societal norms.

As I detail in the work following this piece – The Missing Story of Mary Burns (which should be regarded as the same work as this) -, poverty has become a sort of descending double signifier in the same way financial wealth has become an ascending double signifier.

These realities intersected in the life of Mary Burns resulting in her devaluation and dehumanisation where ultimately her voice was removed to be replaced by silence and overlaid with culturally produced ‘facts’. This silence represents non-recognition, non-acknowledgement, dehumanization, devaluation and an extensive, profound and structural violence which is instituted on those who are uprooted from sufficiency to perform for a hierarchy of privilege that patterns society.

Precarity: Displacement from collective sufficiency of commons

This section of the paper explores the history of law and land reform which created the conditions for a precarious population dispossessed from ancestral rights associated with sufficiency uses of the land. It is important to understand the changing circumstances in which people found themselves in order to apprehend how large populations came to be working in an industrial landscape predominantly in poor conditions and for insufficient remuneration.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

The law demands that we atone

When we take things we do not own

But leaves the lords and ladies fine

Who takes things that are yours and mine.

The poor and wretched don’t escape

If they conspire the law to break;

This must be so but they endure

Those who conspire to make the law.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back.

“This 17th Century folk poem is one of the pithiest condemnations of the English enclosure movement—the process of fencing off common land and turning it into private property. In a few lines, the poem manages to criticize double standards, expose the artificial and controversial nature of property rights, and take a slap at the legitimacy of state power. And it does it all with humor, without jargon, and in rhyming couplets.” (Boyle, 2001)

—James Boyle, Duke Law School Professor

Boyle, J. (2001) Celebrating The Commons; People, Ideas, and Stories for a New Year, On the Commons, onthecommons.org, http://onthecommons.org/sites/default/files/celebrating-the-commons.pdf, Page 45

This work analyses the creation of classes of people who’s existence is rooted in working (compelled performance) via the production of precarity based on their dispossession from natural commons as forms of sustaining wealth. Precariousness describes primary qualities of life which embody uncertain and unhealthy existence; ones which lack predictability and the affordances of planning, security of income through remuneration for labour as a feature, and sufficiency of material and psychological aspects important for wellbeing.

This section examines how displacement of populations from the means of sufficiency farming over centuries has created large urbanized populations which exist under conditions of precarity having been made dependent on inclusion in hierarchies of financial status chiefly expressed through opportunities of workfulness and the valuation of their labour. I argue that this enclosing/enclosure of sufficiency extends to the present day through enclosure of portions of human capital (for example, with intellectual property and professional qualification) traditionally inalienably associated with the individual as the means of reification had not been developed (i.e. highly organised ‘qualifications’, bureaucracies, technocratic financial systems, etc).

Historically, common land as a means of populations maintaining sufficiency was land shared collectively by a number of persons. The same sense of explicit legal ownership we have today did not exist in terms of organised and formalised property rights; instead a shared understanding of ancient associations with the land pervaded public consciousness. Most commons are based upon ancient ancestral rights in British common law which pre-date the statute law passed by the Parliament of England. An individual who has a right to draw their subsistence from common land jointly with others was understood as a commoner and as a part of the commons people. People retained traditional rights such as allowing their livestock to graze, collecting and coppicing wood (estovers), and cutting turf for fuel. It is from the 13th century onwards in Britain we see an initial concentrating effect of ownership into the hands of single individuals.

Sir George Laurence Gomme wrote about traditional rights such as the ancient belief associated with homemaking on land in his book on ‘The Village Community’: “it will be found that our examination of the village house structure in England leads us to perceive that it is intimately connected with the primitive Aryan principle of the sacredness of the homestead. The group of buildings making up the homestead is centred round that portion which contains the sacred house-fire…The preservation of the old chimney-stack of ancient dwellings while all else has been rebuilt and the right of house-bote attached thereto; the old tenure locally called ‘keyhole’ tenure in Hampshire, by which, if a squatter could build a house or hut in one night, and get his fire lighted before the morning, he could not be disturbed; the demolition of the homestead as a sign of loss of village rights, taken in connection with a law of Canute which lays it down that housebreaking is an inexpiable crime, punishable only with death”

“The story of Germanus having found shelter in a villager’s house, and so preserved it from the fire which destroyed all the other houses in the village, reveals the collection of the homesteads into villages instead of in tribal homesteads (lib. i. cap. xix.) ; while the story of the sanctity shown by the earth taken from St. Oswald’s grave not only shows us the village homestead, but reveals at least one important feature of primitive house life, namely, the situation of the central fire in the middle of the room (lib. iii. cap. x.)—an arrangement prevalent in Scotland so recently as the latter part of the last century.

Following up this clue, it will be found that our examination of the village house structure in England leads us to perceive that it is intimately connected with the primitive Aryan principle of the sacredness of the homestead. The group of buildings making up the homestead is centred round that portion which contains the sacred house-fire, and it has been remarked with truth that ” it is no fanciful metaphor to say that the house-fire is the seed out of which the house has grown.”

If the architecture of the old village homestead reveals this much to us, custom tells us something more. The preservation of the old chimney-stack of ancient dwellings while all else has been rebuilt and the right of house-bote attached thereto; the old tenure locally called ‘keyhole’ tenure in Hampshire, by which, if a squatter could build a house or hut in one night, and get his fire lighted before the morning, he could not be disturbed; the demolition of the homestead as a sign of loss of village rights, taken in connection with a law of Canute which lays it down that housebreaking is an inexpiable crime, punishable only with death; seem to me to connect the house unmistakably with the old hearth cult.

And the importance of this as a potent force in keeping together old forms of society may be to some extent measured if we bear in mind what Dr. Hearn has so strongly and ably set forth of Aryan society, that ‘it was not the tie of blood, or of family habit, or of superior physical force that held men together, but the far more potent bond of a common worship. Those who worshipped the same gods were relatives.'”

P. 128, Gomme, S. G. L. (1912). The Village Community; With special reference to the origin and form of its survival in Britain. London: W. Scott, New York, Scribner.

Feudalism has come to be a very loose term to allude to suggested arrangements of legal and military relationships among ‘nobles’ and ‘serfs’ between the 9th and 15th centuries. To a significant extent it is a construction of later centuries to account for a past order of things from which ‘manorialism’ extended; a suggested scheme of legitimacy presiding over the legal and economic relationships between ‘nobles’ and ‘peasants’.

Susan Reyolds (2001) brings a new reinterpretation of what we have received as the order of things in Medieval Europe. Her work has caused a shift in the use of language alongside an unsettling of romanticised notions of noble and serf debunking the myth of pyramidal feudal society in early medieval times. According to Reynolds the ideas come to be associated with feudalism would not have been recognised by many in the medieval period; certainly before 1066 the structure of relations between peoples and property rights was not so hierarchical as it as become painted:

“The concept of a hierarchy of property rights probably owes a good deal to Domesday Book, although it only came to be articulated during the twelfth century, when rights and obligations were worked out and enforced according to the way they had been set down in 1086. The very word hierarchy may, however, be misleading: property rights were arranged in layers, but the top layer did not have most rights. Most of the rights of property, including the fundamental rights to use, management, and receipt of the income, were enjoyed, as they were elsewhere, by those at the lowest layer above that of unfree peasants. Except in the case of property held by military service by heiresses or minor heirs, the rights of a lord in the layer above were restricted to certain dues and services: the king, of course, did better, but it still remains true that more rights of property belonged to those who came to be called tenants in demesne”

“If, as long tradition asserts, feudalism was introduced into England by the Norman Conquest, then, whether it is seen in military terms as a matter of knights’ fees and knight service or in jurisdictional terms as a matter of seigniorial courts, it was a pretty fugitive affair which barely outlasted its first century. If it is seen as already developing before 1066 then it might be said to have lasted longer, but the arguments for that, whether in terms of military service or of a tenurial hierarchy, seem hard to sustain.

The introduction of the word fief and a new concept of a hierarchy of property rights seem to be genuine consequences of the conquest. The concept of a hierarchy of property rights probably owes a good deal to Domesday Book, although it only came to be articulated during the twelfth century, when rights and obligations were worked out and enforced according to the way they had been set down in 1086. The very word hierarchy may, however, be misleading: property rights were arranged in layers, but the top layer did not have most rights.

Most of the rights of property, including the fundamental rights to use, management, and receipt of the income, were enjoyed, as they were elsewhere, by those at the lowest layer above that of unfree peasants. Except in the case of property held by military service by heiresses or minor heirs, the rights of a lord in the layer above were restricted to certain dues and services: the king, of course, did better, but it still remains true that more rights of property belonged to those who came to be called tenants in demesne than to either the king or any other lord.”

Reynolds, S. (2001). Fiefs and vassals: The medieval evidence reinterpreted. Oxford: Clarendon Press. page 394

Over the centuries we have seen a trend in the concentration of ownership of land and its associated means of sufficiency into smaller and smaller numbers of people. The most alluded to period in the history of Britain that illustrates this trend is that of the Enclosure Movement which took place between 1750 and 1850. Here the policy drive was expressed as a strategy to improve agricultural production and this kind of land management and social engineering project took place in various parts of the world.

James Alfred Yelling argues it is important to understand that Enclosure was not one key step that released commercial or capitalist forces into the agrarian regime (Yelling, 1977). More broadly it can be seen as a pattern of legal process in England emerging from the 13th century onward which consolidated (enclosing) small landholdings into larger farms. Once enclosed, use of the land was restricted and available only to the owner as it had legally ceased to be common land for communal use. This signaled the beginning of the practical ending to the ancient system of arable farming in open fields.

Yelling argues that it was in effect the emergence of a new economic and social order. There were “close links between enclosure and the commercialisation of agriculture, but the one was not a necessary cause of the other…Common field and enclosure coexisted over many centuries, juxtaposed at various levels from farm and township to the large-scale region”.

He gives varying examples of the attribution of enclosure: “in particular cases to population growth, to population decline, to the presence of soils favourable or unfavourable to arable, to industrial and urban growth, to remoteness from markets, to the dominance of manorial lords, to the absence of strict manorial control, to increased flexibility in the common-field system, and to the absence of such flexibility”.

Yelling, J. A. (1977). Common field and the enclosure in England: 1450-1850. London: The MacMillan Press. Page 3-4

The history of the re-organisation of land management can be understood over a period of a number of centuries. Perhaps the emergence of this new economic and social order can be understood in a pattern of behaviour which gained increasing adherents over time.

Gordon E. Mingay suggests “It should not be assumed, however, that historians have been entirely mistaken in attaching so much importance to parliamentary enclosure” (Mingay, 2016) which took place through several Acts of Inclosure passed between 1773 and 1882. It clearly had a long prehistory, and, in terms of land, Brett Christophers argues that this behaviour continues to this day in his book ‘The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain‘ (Christophers, 2019).

“Until the era of cheap under-drainage and the introduction of roots suited to heavy soils (such as the mangold) in the middle nineteenth century, the cold wet clay lands could not be adapted to the new husbandry, and on these soils the ancient rotations long survived enclosure. It should not be assumed, however, that historians have been entirely mistaken in attaching so much importance to parliamentary enclosure. It meant a rapid accession to the cultivated area of large tracts of commons and waste, and for the common fields a rapid conversion to the conditions necessary for more efficient farming.

Not all villages had made much progress in adjusting their common-field farming to take advantage of the new possibilities of greater fertility and greater output: Young’s strictures on the ‘goths and vandals’ of the common fields and his view, expressed as late as 1809, that ‘the old open-field school must die off before new ideas can become generally rooted’; must have had some considerable justification in the conservatism of small farmers.

The common-field system was wasteful, expensive, and difficult to work so long as dispersed holdings, common grazing rights, and sharing of the commons remained its basis. Enclosure offered a means of rapid transformation to lower costs per acre, higher yields, and greater profits on a larger cultivated area. It was profitable to landlords, whose increase in rents usually represented a return of 15-20 per cent or more on the outlay, and it must have been correspondingly profitable to the farmers whose greater productivity allowed them to pay much increased rents.

The concentration of enclosure in periods of rising prices show that it was considerably influenced by the desire of landowners and farmers to take advantage of the market more readily and more completely than could be done under the limitations of the common fields, and the number of enclosure Actssome 5,000 in the two periods of heavy activity in the 1760s-70s and 1795-1815 – gives some indication of the scale of the change. Parliamentary enclosure thus gave a sharp fillip to improved methods of farming where conditions allowed them to be adopted. There seems little doubt, too, that generally the improved farming was more suited to farms of at least a moderate size (say above about 100 acres) and to farmers commanding capital.”

Mingay, G. E. (2016). Enclosure and the Small Farmer in the Age of the Industrial Revolution. London: Macmillan Education, Limited. Page 19

“The scope of this particular component of the wider project of British privatization has never before been explicitly considered, but here it has been laid bare. Even if we exclude all the land that has disappeared with Britain’s ‘other’ privatizations, just over 1.6 million hectares – or about 8 per cent of the entire British land mass – have been transferred from public into private ownership since Thatcher came to power. If we add to this the land owned by the water utilities and the other formerly public enterprises now in private hands, the figure jumps to around 2 million hectares. That represents approximately half of all the land that was publicly owned when the 1970s drew to a close. Local authority landholdings, in particular, have been decimated, with around 60 per cent of the local government estate having been ‘rationalized’. The result is that, today, only approximately 2.2 million hectares of public land remain.”

Christophers, B. (2019). The new enclosure: The appropriation of public land in neoliberal Britain. Page 276

Property rights started to crystalise when lodgers and the subdivision of houses were declared not to be legitimate by dint of the monarch’s overarching allodial title. This is mainly by effect of the passing of the statutes ‘Quia Emptores‘ and ‘Quo Warranto‘ by the Parliament of England in 1290 during the reign of Edward I. Thereafter manors could not be created as the law expresses that manorial courts could not be established with legal jurisdiction.

These statutes were constructed to rule on land ownership disputes and consequent financial controversies in England. The name Quia Emptores comes from the first two words of the statute in its Latin form, which translates as “because the buyers”. Its full title translates as ‘A Statute of our Lord The King, concerning the Selling and Buying of Land’.

The statute of Quia Emptores prevented tenants from alienating their lands (land acquired from customary landowners by the government, either for its own use or for private development) to others by subinfeudation (the practice by which tenants, holding land under the monarch or other ranking lord, created new tenures in their turn through sub-letting or ‘alienating’ a part of their lands). Instead all tenants who wished to alienate their land were required to do so by substitution (the person who was granted the land was to hold it for the same immediate lord, and by the same services as the alienor who held it before).

The statute of Quo Warranto derives from the Latin meaning “by what warrant?”. It is a prerogative writ requiring the person to whom it is directed to demonstrate what authority they have for exercising a right, power, or franchise they are laying claim to.

The long term effect of the statutory law passed in the 13th century was to create lineages of ownership which prevented new ownership or redistribution of lands to entrepreneurial individuals who might increase their standing through becoming land owners. Built on these foundations the Erection of Cottages Act 1588 (31 Eliz c. 7, long title “An Act against the erecting and maintaining of Cottages”) enclosed commons land from the ancestral tradition of home-making without appeal to the lord of the manor.

Exemption from this Act could be obtained by petition at four times of the year based on grounds of poverty. This permission was sought from the person who held the title of lordship of a given manor. The Manorial system described the system of landowners in the Middle Ages and in Tudor and Stuart times

In the same period, the Poor Law Act of 1601 had been passed into statute – which remained largely operative until the twentieth century; in many respects it was a refinement of the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1597 which devolved authority and responsibility for the poor to individual parishes. The combined aims of the Statute of Artificers and the Poor Laws were Acts express an ideology “that would banish idleness, advance husbandry, and pay proper wages to the laborers”.

This was qualified by ‘An Act for the Relief of the Poor’ passed in 1601. It gave churchwardens and overseers the authority to build cottages on ‘waste and common’ for the use of the poor and inmates, with permission of the manorial lord. In the same Act we also see how the labour of children could be legally bound to indentureship by Churchwardens and Overseers. This servitude could be taken from male children until the age of 24 and from female children until the age of 21 (or the time when she was married) (Basket,1763, p703).

“For the Avoiding of the great Inconveniences which are found by Experience to grow by the Erecting and Building of great Numbers and Multitude of Cottages, which are daily more and more increased in many Parts of this Realm (2) Be it enacted by the Queen’s most excellent Majesty, and the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and the Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the Authority of the fame, That after the End of this Session of Parliament, no Person shall within this Realm of England make, build or erect, or cause to be made, builded or erected, any Manner of Cottage for Habitation or Dwelling, nor convert or ordain any Building or Housing made or hereafter to be made, to be used as a Cottage for Habitation or Dwelling, unless the same Person do assign and lay to the same Cottage or Building four Acres of Ground at the least, to be accounted according to the Statute or Ordinance de terris menfurandis being his or her own Freehold or Inheritance lying near to the said Cottage, to be continually occupied and manured therewith, so long as the same Cottage shall be inhabited ; (5) upon Pain that every such Offender shall forfeit to our Sovereign Lady the Queen’s Majesty, her Heirs and Successors, ten Pounds of lawful Money of England, for every such Offence.

II. And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That every Person which after the End of this session of Parliament shall willingly uphold, maintain and continue any such Cottage hereafter to be eroded, converted or ordained for Habitation or Dwelling, whereunto four Acres of Ground, as it aforesaid shall not be assigned and said to be used and occupied with the same, shall forfeit to our said Sovereign Lady the Queens Majesty, her Heirs and Successors, forty Shillings for every Month that any such Cottage shall be by him or than upholden, maintained and continued.

Ill. And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That all Justices of Assizes and Justices of Peace in their own Sessions, and every Lord within the Precinct of his Leet, and no other, shall have full Power and Authority within their several limits and jurisdictions, to enquire of, hear and determine all Offences contrary to this present Act, as well by Indictment, as otherwise by Presentment or Information: (a) and to award Execution for the levying of the several Forfeitures aforesaid by fieri facias, elegit, capias or otherwise, as the cause shall require.

IV. Provided always That this Statute, or any Thing therein contained, shall not in any wise be extended to any Cottage which shall be ordained or eroded to or for Habitation or Dwelling in any City, Town Corporate, or ancient Borough or Market-Town within this Realm, (2) nor to any Cottage or Buildings which shall be erected, ordained or converted to and for the necessary and convenient Habitation or Dwelling of any Workmen or Labourers in any Mineral Works, Cool Mines, Quarries or Delft of Stone or Slate, or in or about the Making of Brick, Tile, Lime or Coals within this Realm ; so as the same Cottages or Buildings be not above one Mile distant from the PIace of the same Mineral or other Works, and shall be used only for the Habitation and Dwelling of the said Workmen ; (j) nor shall in any Sort prejudice, charge or impeach any Person or Persons for the Eroding, Maintaining or continuing of any such Cottages, as are before in this Proviso mentioned and specified.

V. Provided always, That this Act shall not extend to any Cottage to be made within a Mile of the Sea, or upon the Side of such Part of any navigable River where the Admiral ought to have Jurisdiction, so long as no other Person shall therein inhabit but a Sailor, or Man of manual Occupation to or for making, furnishing or victualling of any Ship or Vessel used to serve on the Sea ; ( 2 ) nor to any Cottage to be made in any Forest, Chase, Warren or Park , so long as no other Person shall therein inhabit but an Under-keeper or Warrener, for the good keeping of the Deer, or other Game or Warren ; (3) nor to any Cottage heretofore made, so long as no other Person shall therein inhabit but a Common Herd-man or Shepherd, for keeping the Cattle or Sheep of the Town, or a poor, lame, sick, aged or impotent Person; (4) nor to any Cottage to be made, which for any just Respect upon Complaint to the Justice of Assize at the Assizes, or the Justices of Peace at the Quarter-Sessions, shall by their Order entred in open Assizes or Quarter- Sessions, be decreed to continue for Habitation, for and during so long Time only as by such Decree shall be tolerated and limited.

VI. Provided also, and be it enacted, That from and after the Feast of All-Saints next coming there shall not be any Inmate, or more Families or Households than one, dwelling or Inhabiting in any one Cottage, made or to be made or erected ; (2) upon Pain that every Owner or Occupier of any such Cottage, plaoing, or willingly fuffcring any such Inmate, or other family than one, shall forfeit and lose to the Lord of the Leet, within which such Cottage shall be the Sum of ten Shillings of lawful Money of England for every Month that any such Inmate, or other Family than one, shall dwell or inhabit in any one Cottage as aforefaid: (3) And that all and every Lord and Lords of Leet and Leets, and their Stewards, within the Precinct of his and their Leet and Leets, shall have full Power and Authority within their several Leets to enquire, and to take Presentment by the Oath of Jurors, of all and every Offence and Offences in this Behalf; (4) and upon such Presentment had or made, to levy by Distress to the Use of the Lord of the Leet all such Sums of Money as so shall be forfeited : (5) And moreover, that it shall be lawful for the Lord of every such Leet where such Presentment shall be made, to recover to his own Use any such Forfeiture, by Action of Debt, in any of the Queen’s Majefty’s Courts of Record, wherein no Essoin, Protection or Wager of Law shall be allowed. 35 Eliz. cap. o. 43 Eliz. cap. 2.”

It is in this period that we can see the early structures of merchantialist-capitalism being forged from feudo-manorial holdings in the Renaissance era – the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries.

Eli Hecksher details in his book ‘Mercantilism’ that it was during this period that England expressed protectionist policies through general internal economic regulation. A critical moment in this was the Labour Law of 1563 put into place by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, in the Statute of Artificers (5 Eliz. c. 4) which Adam Smith referred to as the “Statute of Apprenticeship” (Page 226, Heckscher, 1994)..

“The circumstance that no single branch of economic life was preferentially treated in England laid the foundation of a deep-set difference between English and continental policy, a difference which found its last expression in the specifically English form of mercantilist protection, the protection of agriculture and industry combined, or the “system of solidarity”.

It was, however, only at a comparatively late period that a protectionist system of this kind arose, and its treatment belongs to the third section of this work, in which mercantilism as a protectionist system is dealt with. The point at issue here is the general internal economic regulation, in which the same tendency was manifested much earlier and in more mature form especially in the famous Labour Law of 1563 called by Adam Smith the “Statute of Apprenticeship”, but nowadays more often quoted as the Statute of Artificers (5 Eliz. c. 4), the work of William Cecil, Lord Burghley.

It was one of the most remarkable results of English economic policy. In spite of the much greater activity of the French monarchs in their heyday, neither in France nor in any other country is it possible to find any other attempt at so thorough a control of the whole industry of a country during the mercantilist period. Its origins and formation are particularly able to throw light on the characteristic features of English development.

The circumstance which provided the real motive for the enactment of the Statute of Artificers operated elsewhere, especially in France, as well as in England. In England too (see above 138 and 141) it was the enormous rise in wages after the Black Death which led to state interference. From that date the regulation of wages ceased to be a local affair and became a national problem.

The national regulation of wages is to be found in the Ordinance of Labourers and the Statute of Labourers enacted in 1349 and 1351 respectively, and in them it is already possible to perceive two closely connected and very essential divergences from the French decree of John the Good, likewise enacted in 1351. The latter held only for the Paris district whilst the former included all England in its scope and created a great judicial system, which covered the whole land and was very extensively employed.

The second difference is closely bound up with the first. The French decree regulated mostly urban trades, whilst the English law was designed to fix the wages for every person who was in the service of another, and in practice the English measures were preferentially applied to rural workers. T h e fundamental ideas of both these decrees were later reproduced without any essential modification in the Elizabethan Statute of Artificers, which on its own admission merely attempted a codification of older rules.

Of the laws which were passed between 1349-51 and 1563, that of 1388 (12 Rich. II cc. 3-10) was specially important. It shows clearly that legislative attention was directed mainly towards agriculture, thus providing a striking contrast to continental tendencies. It stated, for instance, that whoever had worked on the land until the age of twelve must remain on it and was not to be admitted to handicraft. Contracts of apprenticeship not in accordance with this ruling were consequently to be annulled.

Another clause, also illustrating the preoccupation with agriculture, proclaimed that “as well artificers and people of mystery as servants and apprentices, which be of no great avoyr (i.e., reputation) and of which craft or mystery a man hath no great need in harvest-time, shall be compelled to serve in harvest, to cut, gather and bring in the corn”. The Statute of Artificers Out of these medieval laws, mentioned here very briefly, the Elizabethan Statute of Artificers created a whole legal system which with the exception of a few unimportant points remained on the Statute Book until 1813 and 1814.”

Heckscher, E. F. (1994). Mercantilism. Routledge: Taylor and Francis. Page 226

The statute had been brought into force by William Cecil also known as Lord Burghley, Elizabeth I’s Lord Treasurer. Hecksher makes the point that “neither in France nor in any other country is it possible to find any other attempt at so thorough a control of the whole industry of a country during the mercantilist period”.

Professor Patrick Atiyah discusses how there is a tendency to discount the notion that the Governments of Elizabeth I’s reign had attempted to control the national economy. He details how three central goals were the focus of the introduction of a substantial amount of regulation over existing human ecologies in Britain. These involved the regulation of labour, the ‘encouragement’ of key industries and the ‘advancement’ of agriculture.

The Statute of Artificers Act imposed the following (Atiyah, 2003, p.67):

- Control of entry into the class of skilled workmen via compulsory seven year apprenticeship

- Reservation of superior trades for the sons of the better off

- Assumption of universal obligation to work on all who are able bodied

- Empowerment of justices to require unemployed artificers to work in husbandry

- Requirement of permission for a workman to transfer from one employer to another

- Severe restriction of the freedom of movement of the poor

- Enablement of justices to remove people to their original parish or place of settlement

- Enablement of justices to fix wage rates for nearly all classes of workmen

“The decline of the overall moral authority of the Church in the medieval economy was not immediately followed by a free for all; it was rather followed by two hundred years during which the state attempted to fulfil the role formerly played by the Church, with its secular laws substituting, somewhat half-heartedly perhaps, for the laws of God. Modern economic historians tend to discount the notion that the Governments of Elizabeth I’s reign ever attempted an overall control of the national economy, but the fact remains that they pursued three goals which, taken together, involved a substantial measure of regulation.

These three goals had as their basic aims the regulation of the labour force, the encouragement of key industries, especially shipbuilding, and the advancement of agriculture. The labour force was, in many ways, the subject of the greatest degree of regulation. The Statute of Artificers (usually called the Statute of Apprentices) was passed in 1563 and remained on the Statute book until 1819; the Poor Law Act of 1601—which provided for much else besides poor relief—remained largely operative until the twentieth century.

Between them, these Acts attempted ‘to banish idleness, to advance husbandry and to yield to the hired person, both in times of scarcity and in times of plenty, a convenient proportion of wages’. They controlled entry into the class of skilled workmen by providing for a compulsory seven years’ apprenticeship; they reserved the superior trades for the sons of the better off; they assumed a universal duty to work on all the able-bodied; and empowered justices to require unemployed artificers to work in husbandry; they required permission for a workman to transfer from one employer to another; they severely restricted the freedom of movement of the poor by enabling a person without means to be removed by order of the justices to his original parish or last place of settlement; and they empowered justices to fix wage rates for virtually all classes of workmen.

On the other hand, there was a quid pro quo for all this: the Poor Law recognized the right of the indigent to poor relief, to be provided at the charge of the parish, and there were also other provisions for the benefit of labourers and artisans such as attempts to ensure that they were employed under contracts of a year’s duration.”

Atiyah, P. S. (2003). The rise and fall of freedom of contract. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Page 67

Here we see a type of enclosure of skill and labour which had not been seen before. The Statute of Artificers (aka Statute of Apprentices) passed in 1563 represented the introduction of the greatest degree of regulation. This statute remained active on the Statute book until 1819, interestingly the same year as the Peter’s Field protest took place in Manchester where 60,000 people gathered to call for representation and parliamentary reform; in response to this peaceful protest 18 were killed and an estimated 400 – 700 people were injured resulting in the travesty being named the Peterloo Massacre.

In the same period, the Poor Law Act of 1601 was passed into statute – which Atiyah states remained largely operative until the twentieth century; in many respects it was a refinement of the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1597 which devolved authority and responsibility in the law to individual parishes. The combined aims of the Statute of Artificers and the Poor Laws were Acts which express an ideological position “that would banish idleness, advance husbandry, and pay proper wages to the laborers”.

England had seen an enormous rise in wages after the Black Death which provoked state interference. The regulation of wages stopped being a local affair and became dictated through national regulation. The national regulation of wages is found in the earlier Ordinance of Labourers and the Statute of Labourers enacted in 1349 and 1351 respectively. Heckscher points out that the ideas of both these earlier statutes were later reproduced in the Elizabethan Statute of Artificers without any significant modification. (Heckscher, 1994,Page 226).

The poet Edmund Spenser voiced a hated for the ideas of William Cecil aka Burghley. One of the moods Spenser set around Burghley came of a piece of writing lampooning him as a nepotistic “malicious, Machiavellian fox who steals the crown of his sovereign to aid the prospects of his ‘cubs’”.

All offices, all leases by him lept,

And of them all whatso he likte, he kept.

Iustice he solde iniustice for to buy,

And for to purchase for his progeny.

Ill might it prosper, that ill gotten was,

But so he got it, little did he pas.

He fed his cubs with fat of all the soyle,

And with the sweete of others sweating toyle,

He crammed them with crumbs of Benefices,

And fild their mouthes with meeds of malefices,

He cloathed them with all colours saue white,

And loded them with lordships and with might,

So much as they were able well to beare,

That with the weight their backs nigh broken were.

Page 162, Danner, B. (2011). Edmund Spenser’s War on Lord Burghley. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

The restriction of freedom of movement of the poor through statute was added to by the legislative prohibition of travelling peoples to make a homestead as they moved. The histories of diasporic and travelling peoples are often obscured for the reason that they have been systematically excluded and what stories written about them have been written by people who are a part of an enfranchised culture looking on.

There may be significance in the connection between the acts of parliament prohibiting free movement, those which locked Travelers from using the land and the coincident historical accounts of Gypsies in England. The identities of travelling people remain fairly mysterious as David Mayall writes: “They have perhaps been excluded from the histories of immigration, as it was forgotten, or not even realised, that Gypsies did not arrive in England until the early sixteenth century”. It raises questions about whether significant subpopulations prior to the restriction of movement by British statute moved around the country with the seasons, and whether ‘Gypsy’ the word became proxy for those who attempted circumvent the law.

“Historians have come rather late to Gypsy studies, and to a large extent the study of Gypsies has usually been undertaken outside the world of mainstream academic history. The likely reasons for such neglect are many. The group is numerically small, so contributing to their invisibility, although this has not prevented investigation into the Polish, Chinese, German or Lithuanian communities in Britain.

They have perhaps been excluded from the histories of immigration, as it was forgotten, or not even realised, that Gypsies did not arrive in England until the early sixteenth century. Also, of course, there remain doubts as to whether Gypsies constitute a distinct and separate minority. These factors have meant that the Gypsies have remained largely marginal within the historical studies discipline, relegated to footnotes, included as one small part of the criminal or vagrant population, or ignored altogether.

It would be misleading, though, to suggest that Gypsies have been entirely abandoned by the historical profession, and the neglect by historians has been relative rather than absolute. In recent studies it is possible to find increasing mention of Gypsies in works on criminality and the underworld,20 on immigration and minority groups,21 in works looking at the lower classes and migrancy,22 and in recent studies of the Nazi state and the Holocaust.”

Page 27, Mayall, D. (2004). Gypsy identities, 1500-2000: From Egipcyans and Moon-men to the ethnic Romany. London: Routledge.

Exemption from the Elizabethan Erection of Cottages Act 1588 could be obtained by petition at four times of the year based on grounds of poverty. This permission was sought from the person who held the title of lordship of a given manor. The Manorial system described the system of landowners in the Middle Ages and in Tudor and Stuart times

The creation of a manor arose via a grant from the crown on paying a fee. An estate was given over from the monarch’s allodial title (a term meaning ownership of real property that is independent of any superior landlord). Details of this can be found in Perkins’s Treatise on the laws of England (Perkins, 1792) illustrating the terms of tenure:

“670. If lord and tenant have been before the statute, of two acres of land, and the tenant do thereof enfeoff a stranger, to hold one acre of the lord paramount, and to hold the other acre of him, the same is good. And it is to know, that the beginning of a manor was, when the king gave a thousand acres of lands, or a greater or lesser parcel of land unto one of his subjects, and his heirs, to hold of him, and his heirs, which tenure is knights service at the least. And the donee did perhaps build a mansion-house upon parcel of the same land, and of twenty acres, parcel of that which remained, or of a greater or lesser parcel before the statute of Quia emptores, &c. did enfeoff a stranger, to hold of him, and his heirs, as of the same mansion-house, to plow ten acres of arable land, parcel of that which remained in his possession, and did enfeoff another of another parcel, &c. to carry his dung unto the land, &c. and did enfeoff another of another parcel thereof, &c. to go with him to war against the Scots, &c. and so by continuance of time he made a manor, &c.”

Page 670 Perkins, J. (1792). A treatise of the laws of England, on the various branches of conveyancing.

In the text ‘enfeoff’ is a verb illustrating to give (someone) freehold property or land in exchange for their pledged service. In the text we can also see mention of the 1290 Quia emptores statute mentioned previously translating to “because the buyers” which makes reference formally to ‘A Statute of our Lord The King, concerning the Selling and Buying of Land’ having the function to prevent tenants from alienating their lands.

A manor was the basic unit of manorialism, which became the dominant economic system during parts of the European Middle Ages. In English, Welsh and Irish law at the time, the lord held a land title (estate in land) which involved the right to hold a manorial court. The court held jurisdiction over most of those who lived within the lands of the manor, the serfs – villeins – cottars – crofters – slaves (bonded tenant living under the condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude) and free peasants (tenant farmers who paid low rents to the manorial lord) who worked various plots of land.

This was qualified by the afore mentioned Act formed in 1597 – ‘An Act for the Relief of the Poor’ and passed in 1601. It gave churchwardens and overseers the authority to build cottages on ‘waste and common’ for the use of the poor and inmates, with permission of the manorial lord

“And be it further enacted, That it shall be lawful for the said Churchwarden and Overseers, or the greater Part of them, by the Assent of any two Justices of the Peace aforesaid, to bind any such Children, as aforesaid, to be Apprentices, where they shall see convenient, till such Man-Child shall come to the Age of four and twenty Years, and such Woman – Child to the Age of one and twenty Years, or the Time of her Marriage; the same to be as effectual to all Purposes, as if such Child were of full Age – and by Indenture of Covenant bound him or her self.

(a) And to the Intent that necessary Places of Habitation may more conveniently be provided for such poor impotent People;

(3) Be it enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That it shall and may be lawful for the said Churchwardens and Overseers, or the greater Part of them, by the Leave of the Lord or Lords of the Manor, whereof any Waste or Common within their Parish is or shall be Parcel, and upon Agreement before with him or them made in Writing, under the Hands and Seals of the said Lord or Lords, or otherwise, according to any Order to be let down by the Justices of Peace of the said County at their General Quarter-Session, or the greater Part of them, by like Leave and Agreement of the said Lord or Lords in writing under his or their Hands and Seals, to erect, build, and set up in fit and convenient Places of Habitation in such Waste or Common, at the general Charges of the Parish, or otherwise of the Hundred or County, as aforesaid, to be taxed, rated and gathered in Manner before expressed, convenient Houses of Dwelling for the said impotent Poor;

(4) and also to place Inmates, or more Families than one in one Cottage or House; one Act made in the one and thirtieth Year of her Majesty’s Reign, intitled, An Act Against The Erection and Maintaining of Cottages or any Thing therein contained to the contrary notwithstanding:

(5) Which Cottages and Places for Inmates shall not at any Time after be used or employed to or for any other Habitation, but only for Impotent and Poor of the same Parish, that shall be there placed from Time to Time by the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of the same Parish, or the most Part of them, upon the Pains and Forfeitures contained in the said former Act made in the said one and thirtieth Year of her Majesty’s Reign”.

p.703 Basket, Mark (1763). Statutes at Large:From the fifth year of King Edward IV to the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth etc. Vol.2. London: Mark Basket et al. https://books.google.nl/books?redir_esc=y&hl=no&id=2KZFAAAAcAAJ&q=An+Act+for+the+Relief+of+the+Poor.#v=onepage&q&f=false

Here in this Act we can also see how the labour of children could be legally bound to indentureship by Churchwardens and Overseers. This servitude could be taken from male children until the age of 24 and from female children until the age of 21 (or the time when she was married).

When discussing enclosure, in general, historical focus has fallen on the parliamentary enclosure era of between about 1760 and 1830. When they required it, the government forced people to give up their former holdings. While it is argued that enclosure ushered in improved agricultural efficiency, at the same time it eradicated the communities and long established ways of life built on self sufficiency that were connected with the land and social networks.

Village populations moved into decline through the displacement of farmers to urban centers. This later coincided with the Industrial Revolution as resettled populations become the workforces of the factories and mills which started to dominate the landscape. Landownership consolidated as small holdings were aggregated into larger farms (Page 384, Rubenstein, 2010).

“To improve agricultural production, a number of European countries converted their rural landscapes from clustered settlements to dispersed patterns. Dispersed settlements were considered more efficient for agriculture than clustered settlements. A prominent example was the enclosure movement in Great Britain, between 1750 and 1850.

The British government transformed the rural landscape by consolidating individually owned strips of land surrounding a village into a single large farm, owned by an individual. When necessary, the government forced people to give up their former holdings. The enclosure movement brought greater agricultural efficiency, but it destroyed the self-contained world of village life. Village populations declined drastically as displaced farmers moved to urban settlements.

Because the enclosure movement coincided with the Industrial Revolution, villagers who were displaced from farming moved to urban settlements and became workers in factories and services. Some villages became the centers of the new, larger farms, but villages that were not centrally located to a new farm’s extensive land holdings were abandoned and replaced with entirely new farmsteads at more strategic locations.

As a result, the isolated, dispersed farmstead, unknown in medieval England, is now a common feature of that country’s rural landscape. As recently as 1800, only 3 percent of Earth’s population lived in cities, and only one city in the world—Beijing—had more than 1 million inhabitants. Two centuries later, one-half of the world’s people live in cities, and more than 400 of them have at least 1 million inhabitants. ”

Rubenstein, J. M. (2010). An Introduction to human geography: The cultural landscape. Boston: Prentice Hall. P384

In Scotland we can see a similar pattern of dispossession of people from sufficiency farming in the form of the highland and lowland clearances. From the work of Prof Tom Devine we can see a slow re-patterning of landuse where crofters and tenants saw their contracts of tenure changed or not renewed (Devine, 1999; Devine, 2011).

Devine, T. M. (1999). The Scottish nation: A history, 1700-2000. New York: Viking.

Devine, T. M. (2011). Clearance and improvement: Land, power and people in Scotland, 1700-1900. Edinburgh: John Donald.

The previous ecology of sufficiency farming had allowed dispersed communities to exist as much in terms of trade and barter but after their uprooting populations had no choice but to operate within a system of centralised finance. The lesser known lowland clearances of Scotland took place between 1760-1830 as landowners bought up and aggregated holdings to form the first ‘superfarms’ (Aitchison & Cassell, 2019).

Aitchison, P., & Cassell, A. (2019). The Lowland clearances: Scotland’s silent revolution, 1760-1830.

E. P. Thompson gives a relatively detailed historical account of the Enclosures in his book ‘Making of the English Working Class’. In it he is clear about his view of the practices: “Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery, played according to fair rules of property and law laid down by a Parliament of property-owners and lawyers”. (Page 218, Thompson, 2016)

“The arguments of the enclosure propagandists were commonly phrased in terms of higher rental values and higher yield per acre. In village after village, enclosure destroyed the scratch-as-scratch-can subsistence economy of the poor-the cow or geese, fuel from the common, gleanings, and all the rest. The cottager without legal proof of rights was rarely compensated. The cottager who was able to establish his claim was left with a parcel of land inadequate for subsistence and a disproportionate share of the very high enclosure costs.

For example, in the enclosure of Barton-on-Humber, where attention was paid to common rights, we find that, out ofnearly 6,000 acres, 63% (3,733 acres) was divided between three people, while fifty-one people were awarded between one and three acres : or, broken down another way, ten owners accounted for 81% of the land enclosed, while the remaining 19% was divided between I I6 people. The average rental value of the arable land enclosed rose in five years (1794-9) from 6s. 6d. to 20S. an acre; and average rentals in the parish were more than trebled.

The point is not to discover an “average” village–diluting Barton with neighbouring Hibaldstow where, apparently, no cottage common rights were allowed, cancelling this out with the exceptional case of Pickering (Yorks) where the householders came out of it better than the landowners…..- but to notice a combination of economic and social tendencies.

Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery, played according to fair rules of property and law laid down by a Parliament of property-owners and lawyers. The object of the operation (higher rents) was attained throughout the Napoleonic Wars. Rents were sustained, not only by higher yields per acre, but also by higher prices: and when prices fell, in 1815-16, and in 182I, rents remained high -or came down, as they always do, tardily-thereby spelling the ruin of many smallholders who had clung on to their few acre holdings gained from enclosure.

High rents sustained extraordinary luxury and ostentatious expenditure among the landowners, while high prices nourished higher social pretentions-so much lamented by Cobbett-among the farmers and their wives. This was the meridian for those “country patriots” whom Byron scorched in his Age of Bronze.”

Page 218 Thompson, E. P. (2016). Making of the English Working Class. Open Road Media.

For the purposes of this paper, what I have been interested in doing is demonstrating a pattern of the increasing concentration of land ownership in smaller and smaller numbers of people over the span of time. This is correlated with the dispossession and resettling of populations from ancestral land and associated practices which were used to draw sufficiency from commons.

Coming forward we can see this pattern of the concentration of ownership continuing. In 1800 only about 3 percent of Earth’s population lived in cities, and only one city in the world had inhabitants of more than 1 million – that of Beijing. Two centuries later we find 50 percent of the world’s people now living in cities, with more than 400 having at least 1 million inhabitants. (Rubenstein, 2010, P384)

We can see that, as a practice, enclosure was not just confined to Britain but took place in other countries too. In Russia around 1900 we can read about how the Stolypin agrarian reforms shifted landownership from the traditional obshchina communally owned form of Russian agriculture towards the development of large scale individually owned farms (khutors) – where ‘peasants’ (from Old French paisent ‘country dweller’) ‘freed of village and family restraints’, were plunged into a demand economy. (Scott, 2020, P. 42)

“The dream of state officials and agrarian reformers, at least since emancipation, was to transform the open-field system into a series of consolidated, independent farmsteads on what they took to be the western European model. They were driven by the desire to break the hold of the community over the individual household and to move from collective taxation of the whole community to a tax on individual landholders. As in France, fiscal goals were very much connected to reigning ideas of agricultural progress.

Under Count Sergei Witte and Petr Stolypin, as George Yaney notes, plans for reform shared a common vision of how things were and how they needed to be: “First tableau: poor peasants, crowded together in villages, suffering from hunger, running into each other with their plows on their tiny strips. Second tableau: agriculture specialist agent leads a few progressive peasants off to new lands, leaving those remaining more room. Third tableau: departing peasants, freed from restraints of strips, set up khutor [integral farmsteads with dwellings]on new fields and adapt latest methods.

Those who remain, freed of village and family restraints, plunge into a demand economy-all are richer, more productive, the cities get fed, and the peasants are not proletarianized.’ It was abundantly clear that the prejudicial attitude toward interstripping was based as much on the autonomy of the Russian village, its illegibility to outsiders, and prevailing dogma about scientific agriculture as it was on hard evidence.’

The state officials and agrarian reformers reasoned that, once given a consolidated, private plot, the peasant would suddenly want to get rich and would organize his household into an efficientworkforce and take up scientificagriculture. The StolypinReform therefore went forward, and cadastral order was brought to both villages in the wake of the reform.”

P. 42, Scott, J. C. (2020). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed.

In 1896 Vilfedo Pareto the Italian economist, sociologist and philosopher did a significant piece of economic work at the University of Lausanne in which he showed that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. This offers another litmus in our layering up of changing land ownership over time.

“The Pareto Principle (also known as the 80-20 rule) states that for many phenomena, about 80% of the consequences are produced by 20% of the causes. In this article we discuss the Pareto Principle and its importance in real life problems, describe some mathematical model related to it and also address the concept of the Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient. We tested two sets of real life data to see if the Pareto principle applies to these aspects.

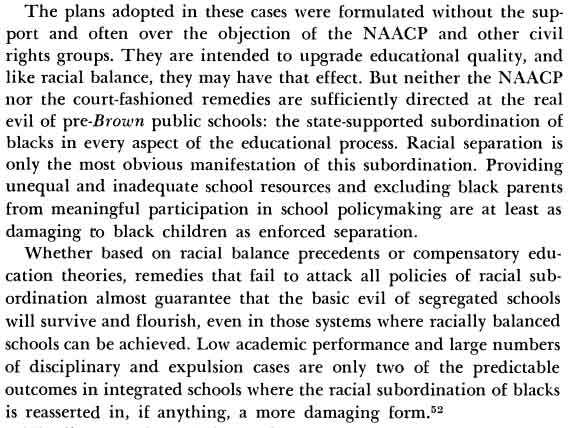

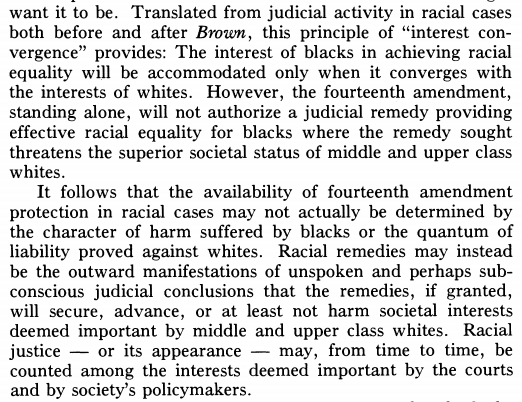

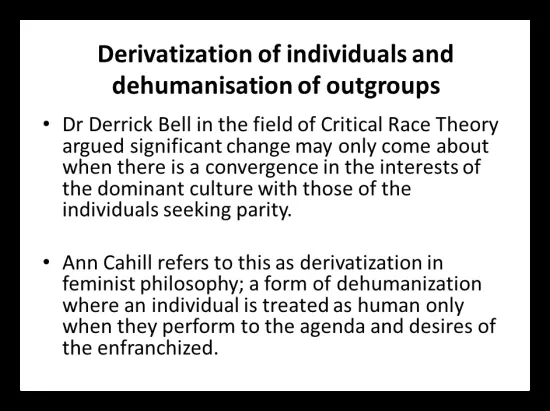

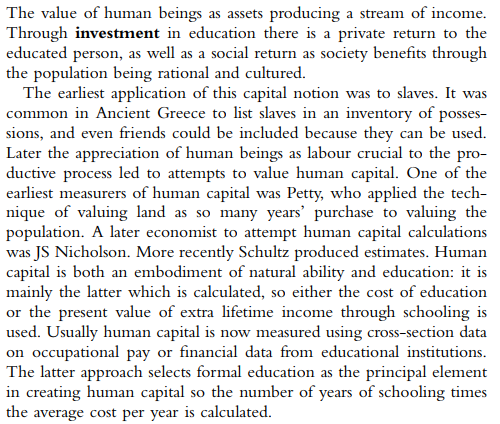

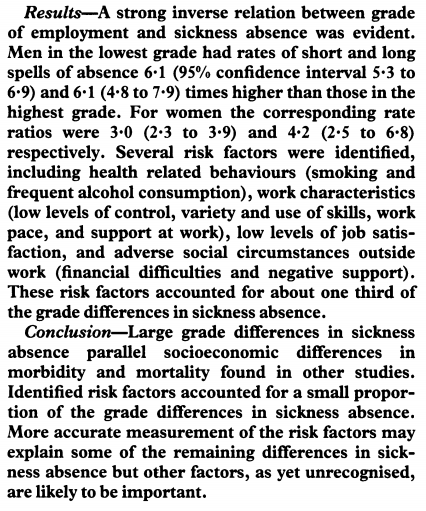

For the Forbes list in 2012, we found that 20% of the richest people own 56.72% of the money. For the world Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2011, 20% of the richest countries in the world have 91.62% of the total amount of money. In both cases results have a relatively close resemblance to the Pareto principle.