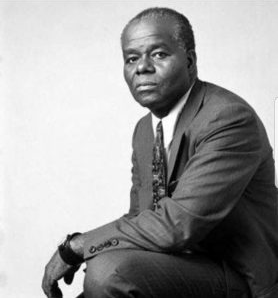

Dr. John Henrik Clarke: Black History as the Lost Pages of Human History

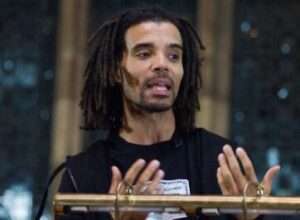

Akala

Text taken from Akala’s Oxford address: 0 min 39 sec – 1 min 5 sec

“The subject of the talk today being ‘Black History as the Lost Pages of Human History‘ actually the quote itself comes from the great Pan-Africanist historian Dr. John Henrik Clarke who spoke about black history in this way and looked at the way in which the history of people of African descent and of Africa itself had to be functionally distorted to justify transatlantic slavery and colonialism in a way that we kind of can’t fully comprehend or understand today.”

The following text is an excerpt from Dr John Henrik Clarke’s essay ‘A Search For Identity‘ (May 1970) which discusses teachers throughout his life and major influences in the development of his scholarship. It offers a written reference and greater context to Henrik talking about Black History as the lost pages of human history.

Henrik writes about the sources of learning through oral history writes about his family as teachers and figures in his personal development which inspired him. The essay charts an emerging criticality around missing and lost histories that revealed the story of the world as he had come to encounter it:

“My own search for an identity began—as I think it begins for all young people—a long time ago when I looked at the world around me and tried to understand what it was all about. My first teacher was my great grandmother whom we called ‘Mom Mary’. She had been a slave first in Georgia and later in Alabama where I was born in Union Springs. It was her who told us the stories about our family and about how it had resisted slavery. More than anything else, she repeatedly told us the story of Buck, her first husband, and how he had been sold to a man who owned a stud farm in Virginia.

Stud farms are an aspect of slavery that has been omitted from the record and about which we do not talk any more. We should remember, however, that there were times in this country when owners used slaves to breed stronger slaves in the same way that a special breed of horse is used to breed other horses.

My great grandmother had three children with Buck—my grandfather Jonah, my grandaunt Liza, who was a midwife, and another child. With Buck, Mom Mary had as close to a marriage as a slave can have—marriage with the permission of the respective masters. Mom Mary had a lifelong love affair with Buck, and years later after the emancipation she went to Virginia and searched for him for three years. She never found him, and she came back to Alabama where she spent the last years of her life.

My Family – Mom Mary was the historian of our family. Years later when I went to Africa and listened to oral historians, I knew that my great grandmother was not very different from the old men and women who sit around in front of their houses and tell the young children the stories of their people—how they came from one place to another, how they searched for safety, and how they tried to resist when the Europeans came to their lands.

This great grandmother was so dear to me that I have deified her in almost the same way that many Africans deify their old people. I think that my search for identity, my search for what the world was about, and my relationship to the world began when I listened to the stories of that old woman. I remember that she always ended the stories in the same way that she said “Good-bye” or “Good morning” to people.

It was always with the reminder, “Run the race, and run it by faith.” She was a deeply religious woman in a highly practical sense. She did not rule out resistance as a form of obedience to God. She thought that the human being should not permit himself to be dehumanized. And her concept of God was so pure and so practical that she could see that resistance to slavery was a form of obedience to God. She did not think that any of us children should be enslaved, and she thought that anyone who had enslaved any one of God’s children had violated the very will of God.

I think Buck’s pride in his manhood was the major force that always made her revere her relationship with him. He was a proud man and he resisted. One of the main reasons for selling him to a man to use on a stud farm was that he could breed strong slaves whose wills the master would then break. This dehumanizing process was a recurring aspect of slavery.

In Columbus I went to county schools, and I was the first member of the family of nine children to learn to read. I did so by picking up signs, grocery handbills, and many other things that people threw away into the street, and by studying the signboards. I knew more about the different brands of cigarettes and what they contained than I knew about the history of the country. I would read the labels on tin cans to see where the products were made, and these scattered things were my first books. I remember one day picking up a leaflet advertising that the Ku Klux Klan was riding again.

Because I had learned to read early, great things were expected of me. I was a Sunday school teacher of the junior class before I was ten years old, and I was the one person who would stop at the different homes in the community to read the Bible to the old ladies. In spite of growing up in such abject poverty, I grew up in a very rich cultural environment that had its oral history and with people who not only cared for me but also pampered me in many ways. I know that his kind of upbringing negates all the modern sociological explanations of black people that assume that everybody who was poor was without love. I had love aplenty and appreciation aplenty, all of which gave me a sense of self-worth that many young black children never develop.

I began my search for my people first in the Bible. I wondered why all the characters—even those who, like Moses, were born in Africa—were white. Reading the description of Christ as swarthy and with hair like sheep’s wool, I wondered why the church depicted him as blond and blue-eyed. Where was the hair like sheep’s wool? Where was the swarthy complexion?

I looked at the map of Africa and I knew Moses had been born in Africa. How did Moses become so white? If he went down to Ethiopia to marry Zeporah, why was Zeporah so white? Who painted the world white? Then I began to search for the definition of myself and my people in relationship to world history, and I began to wonder how we had become lost from the commentary of world history…

…The essay, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” was my introduction to the ancient history of the black people. Years later when I came to New York, I started to search for Arthur A. Schomburg. Finally, one day I went to the 135th Street library and asked a short-tempered clerk to give me a letter to Arthur A. Schomburg. In an abrupt manner she said, “You will have to walk up three flights.”

I did so, and there I saw Arthur Schomburg taking charge of the office containing the Schomburg collection of books relating to African people the world over, while the other staff members were out to lunch. I told him impatiently that I wanted to know the history of my people, and I wanted to know it right now and in the quickest possible way. His patience more than matched my impatience.

He said, ‘Sit down, son. What you are calling African history and Negro history is nothing but the missing pages of world history. You will have to know general history to understand these specific aspects of history.’ He continued patiently, ‘You have to study your oppressor. That’s where your history got lost.’

Then I began to think that at last I will find out how an entire people—my people —disappeared from the respected commentary of human history. It took time for me to learn that there is no easy way to study history. (There is in fact, no easy way to study anything.) It is necessary to understand all the components of history in order to recognize its totality. It is similar to knowing where the tributaries of a river are in order to understand the nature of what made the river so big. Mr. Schomburg, therefore, told me to study general history. He said repeatedly, “Study the history of your oppressor.”

I began to study the general history of Europe, and I discovered that the first rise of Europe—the Greco-Roman period—was a period when Europe “borrowed” very heavily from Africa. This early civilization depended for its very existence on what was taken from African civilization. At that time I studied Europe more that I studied Africa because I was following Mr. Schomburg’s advice, and I found out how and why the slave trade started.

When I returned to Mr. Schomburg, I was ready to start a systematic study of the history of Africa. It was he who is really responsible for what I am and what value I have for the field of African history and the history of black people the world over. I grew up in Harlem during the depression, having come to New York at the age of seventeen.

I was a young depression radical—always studying, always reading, taking advantage of the fact that in New York City I could go into a public library and take out books, read them, bring them back, get some more, and even renew them after six weeks if I hadn’t finished them. It was a joyous experience to be exposed to books. Actually, I went through a period of adjustment because my illegitimate borrowing of books from the Jim Crow library of Columbus, Georgia, had not prepared me to walk freely out of a library with a book without feeling like a thief. It took several years before I really felt that I had every right to go there.

During my period of growing up in Harlem, many black teachers were begging for black students, but they did not have to beg me. Men like Willis N. Huggins, Charles C. Serfait, and Mr. Schomburg literally trained me not only to study African history and black people the world over but to teach this history.”

Thinkers mentioned in above essay:

Willis N. Huggins

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willis_Nathaniel_Huggins

Charles C. Serfait

aaregistry.org/story/charles-seifert-collector-and-teacher-of-black-history/

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arturo_Alfonso_Schomburg

The from the Collected Writings Of: John Henrik Clarke – Web Edition

The above essay was taken from the ‘Collected Writings Of: John Henrik Clarke – Web Edition’. The inscription in the above book reads: “The Writings contained do not represent a selection but merely a collection of the Writings available on the Internet. They are preserved in here too keep them openly available after africawithin.com seems unfortunately to be out of service. Much of the Writings have been taken from there.”

Using the facility of The Internet Archive Waybackmachine much of the content of the africawithin.com website is available to browse online for free. The Waybackmachine is a unique repository of websites which have been published on the internet and when a new website is published, the Waybackmachine takes multiple snapshots of the informational content over time. By visiting web.archive.org and entering the URL of a website which is no longer available on the internet you can access archived copies of websites, sometimes going back 25 years in time.

Why Africana History? By John Henrik Clarke (January 1987)

“Africa and its people are the most written about and the least understood of all of the world’s people. This condition started in the 15th and the 16th centuries with the beginning of the slave trade and the colonialism system. The Europeans not only colonialized most of the world, they began to colonialize information about the world and its people. In order to do this, they had to forget, or pretend to forget, all they had previously known about the Africans.

They were not meeting them for the first tine; there had been another meeting during Greek and Roman times. At that time they complemented each other. The African, Clitus Niger, King of Bactria, was also a Cavalry Commander for Alexander the Great. Most of the Greeks’ thinking was influenced by this contact with the Africans.

The people and the cultures of what is known as Africa are older than the word “Africa.” According to most records, old and new, Africans are the oldest people on the face of the earth. The people now called Africans not only influenced the Greeks and the Romans, they influenced the early world before there was a place called Europe…

To understand fully any aspect of African American life one must realize that the African American is not without a cultural past, though he was many generations removed from it before his achievements in American literature and art commanded any appreciable attention. Africana or Black History should be taught every day, not only in the schools, but also in the home.

African History Month should be every month. We need to learn about all the African people of the world, including those who live in Asia and the islands of the Pacific. In the twenty-first century there will be over one billion African people in the world. We are tomorrow’s people. But, of course, we were yesterday’s people too. With an understanding of our new importance we can change the world, if first we change ourselves.”

Taken from Africa Within website

https://web.archive.org/web/20080916230335/http://www.africawithin.com/home/about.htm

In his essay ‘A Dissenting View‘ John Henrik Clarke identifies a range of scholars and texts which he sees as ‘forerunners of the present propagators of Afrocentricity’ in responding to critiques of scholarship and questions of power relations. The following is Dr. Clarke’s response to ‘Black Demagogues and Pseudo-Scholars‘ drawn from raceandhistory.com (https://www.raceandhistory.com/historicalviews/henrik22.htm):

“In reference to the OP-ED of Henry Louis Gates Jr. the New York Times (Monday, July 20, 1992), entitled ‘Black Demagogues and Pseudo-Scholars,’ I am raising the following questions: At once, I questioned the title of Professor Gates’ article.

He should never refer to anyone as a demagogue unless he’s ready to call the names of the demagogues, singular or plural, and point out the nature of their demagoguery. He should never refer to any scholar as being pseudo, unless he is ready to name the scholar and prove the pseudo nature of his or her work. To disagree with a scholar does not make the scholar a demagogue.

Most of the old and new Black scholars asking for a total reconsideration of African history, in particular, and world history, in general, are using neglected documents by radical White Scholars who are generally neglected by the White academic community.

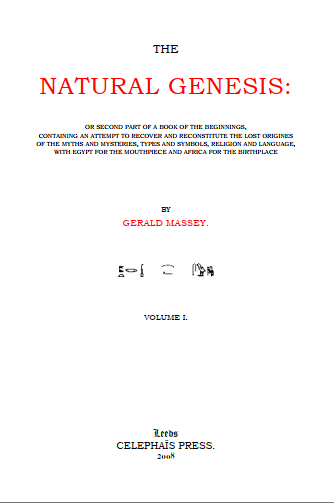

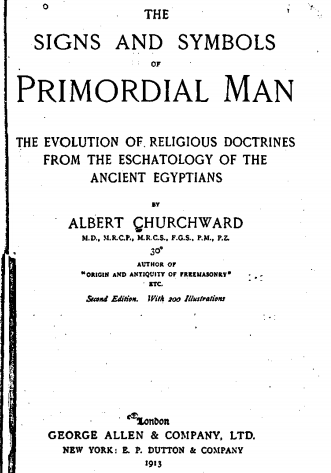

In African history I am referring to scholars like Gerald Massey and his work, Egypt, Light of the World, (two volumes), The Book of the Beginnings, (two volumes) and Natural Genesis, (two volumes). I am also referring to Gerald Massey’s greatest English disciple, Albert Churchward, whose book, The Signs and Symbols of Primordial Man, asks for a reconsideration of the role of people outside of Europe and their role in human development.

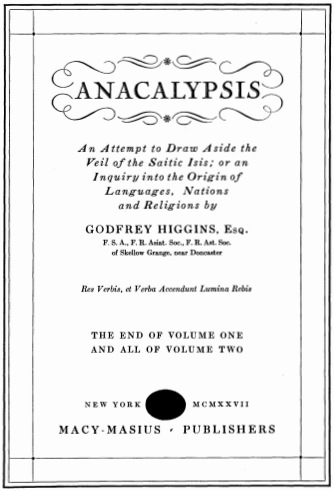

Your attention should also be called to the work, Anacalypsis, two volumes by Godfrey Higgins, published in 1837. These books deal with the dispersions of African people throughout the world. Many of these Black scholars, whose work Professor Gates questioned, were reading works by Whites in French, German and other languages that spoke positively about African American achievement long before Mr. Gates’ parents were born.

This school of Black scholars are neither demagogues nor are they pseudos; they are the forerunners of the present propagators of Afrocentricity. They know what Professor Gates doesn’t seem to know: that African people are the most written about and the least understood people in the world.

If Professor Gates has not read the works of the White pioneer scholars about the role of African people in world history, it stands to reason that he has no understanding of the senior Black scholars such as Yosef ben-Jochannan, John G. Jackson, Cheikh Anta Diop, Jacob Carruthers, Chancellor Williams, Lao Hansberry and myself.”

A Dissenting View by John Henrik Clarke

Thinkers mentioned in above essay:

Yosef ben-Jochannan

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yosef_Ben-Jochannan

Yosef A.A. ben-Jochannan (selected and edited by Itibari M. Zulu), “Philosophy and Opinions”, Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.8, no.10, February 2016, pp. 48–61.

John G. Jackson

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_G._Jackson_(writer)

Cheikh Anta Diop

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheikh_Anta_Diop

Click to download Introduction and Chapter 1

Click to download Introduction and Chapter 1

Click to download Introduction and Chapter 1

Click to download Introduction and Chapter 1

Jacob Carruthers (Jedi Shemsu Jehewty)

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacob_Carruthers

Click to download Introduction and Chapter 1

Chancellor Williams

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chancellor_Williams

Click to download Introduction and Chapter 1

Leo Hansberry

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Leo_Hansberry

John Henrik Clarke

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Henrik_Clarke

Gerald Massey

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_Massey

Albert Churchward

Godfrey Higgins 1837

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godfrey_Higgins

This article is a part of a series of works based on the address which Kingslee James McLean Daley (also known professionally as Akala) gave at Oxford University Students Union; the series will use the address in order to introduce various aspects of Black History. This series is the result of an active attempt at learning from Akala as a contemporary and cutting edge thinker who has done a great deal to shift into the light large tracts of thinking and history which have been obscured deliberately, and in some cases through a social hypnogogia; a slumber state of acceptance.

I shall be referring to Mr Daley as Akala throughout the series due to the visibility of his name as an artist which I feel is important for the public identification of where anyone can go in order to access his considerable body of work. This series cannot be understood as representing Akala’s work and thinking, but can be understood as being based on and inspired by it.

For anyone with deep learning instincts, the important practice will be to engage with his work, and the work of those referenced in this as primary sources – that is, when I as a reader of these thinkers have used someone’s work in order to structure my learning (and my sharing of this), the original authors should be consulted in their own original words, in their own original contexts in order to check for and be able to detect divergences from the original authors thoughts.

This is a practice that is central to any learner, but I suspect it is even more vital in respect to Black History due to the unethical, untoward and unfortunate realities which are bound up in this subject discipline. For me, my own motivations come through a desire to have a better account of history and culture than that which I have been exposed to. I am tired of the senescent cultures of empire and nostalgia in harmful fairytales which are at work. Once cleared from the mind what re-establishes is a much richer world and universe that involves everyone in equity..

I see what has occurred in the obscuring of Black History as a disfigurement of the truth which I see as a form of cultural insanity. This represents an illness capable not only of denuding the future, like it has the past, but also of creating suffering where wealth and joy should be. What have we left if we do not orient towards truthfulness ? So it is with these notes, searches and researches that I share my journey inspired by many individuals I have met, and aided by the nuanced work of Akala who raises powerful questions in a publicly accessible way.

My hope is that I do this work in a respectful way and in a manner which facilitates others not only to learn too but also to think critically about my approach. I have done my best to provide what original sources I can. Readers are invited to get in touch with any corrections, comments and suggestions so that I may be a better student, learner and thinker.

Alex Dunedin