Sylvia Federici Discusses Feminist Responses, Unpaid Labour, Femicide And Institutional Silence

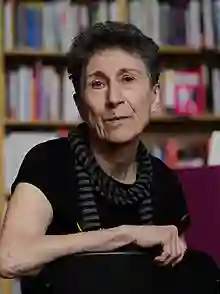

This is a transcript assembled from the above audio recording of a presentation which the thinker and philosopher Sylvia Federici gave at a public talk in the University of Edinburgh event in 2018. The event was hosted by Collective and Talbot Rice Gallery where Federici explored themes of interpersonal and institutional violence against women, as outlined in her latest book, “Witches, Witch-Hunting, and Women.” Federici provides insightful tools for comprehending collective resistance to victimization, both in historical contexts and in contemporary society.

Her book ‘Caliban and the Witch; Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation’ she published with open copyright and holds a great deal of continuity to her 2018 book ‘Witches, Witch Hunting, and Women’. The reader can find a summary of the work at the end of the transcript published here.

The transcript has been made because the audio recording is not a very good one and was made as a matter of public record of a presentation which has particular public value. A transcript has been created for those who find the audio recording too problematic to listen to; it has been annotated with subheadings to help the reader navigate themes. If the reader needs to check some section they can listen to the audio recording and make their own audit. Any suggested corrections to the transcript are welcomed.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgment of the Introduction

Okay, thank you, Jessie, for this beautiful, moving introduction. It is really very much appreciated. Thank you to the shelter for hosting us and to those who have organized this event and allowed it to take place. Thank you to you all. I am very pleased and empowered to see so many people. I know this indicates that something is happening. I understand it’s not just for me; I’m here for an occasion, but this gives me a lot of strength to realize that people want to come together.

The Importance of Our Gathering

I think it’s very important because we live in dangerous times. We live in a world where the system, society, and capitalist society—the foundation of our lives—are dropping their masks. The authorities who sustain the system are shedding their progressive facades and no longer attempting to portray capitalism as a humanitarian system that guarantees prosperity for all. In fact, I acknowledge, in very uncensored terms, that violence, once again, is the most significant social weapon they wield.

Examples of State Violence

For instance, we have the president of the Philippines, who publicly declares that he has killed people. We know he is responsible for thousands of deaths since his election. The newly elected Brazilian president, Bolsonaro, claims he loves the previous dictatorship, stating that their only problem was that they didn’t kill enough people. Our president, Trump, has recently spent no time hiding the fact that he doesn’t care whether Saudi Arabia has killed a journalist who was critically assessing the regime because, after all, we sell a lot of arms to them. Now, why would anyone want to give up the money made from selling arms that are now killing thousands of people?

The Global Context of Violence

I mention this because I think it’s essential to understand the socio-economic and global context in which we are living. Even where violence is not openly embraced in such brutal terms, and amid institutional silence, you may ask: where is the European Union? Where are the United Nations? They no longer present themselves as supporters of human rights. Where are they? There is a profound silence surrounding these statements.

Even when we don’t have such an open embrace of violence, we have had, for decades, policies that implement and institute regimes that dispossess the majority of the world’s population of the means of reproduction essential to their lives, whether it is land, resources, or essential services. This has been a long trend of investments and policies that force millions to leave their homes, their countries, and face very dangerous prospects for the future.

The Mediterranean as a Grave

The Mediterranean is now a mass grave for those who die fleeing from Africa and the Middle East. We have mass graves in the Sahara and at the border of the United States—presumably the richest country on this planet—where people are crossing while fleeing from countries that have been completely devastated by policies incentivized by the United States itself.

The Meaning of Feminism in Today’s World

So, what does it mean to speak in such a world? What does it mean to speak of feminism? This is what I am trying to address in very schematic terms because I am eager for the discussion. I am here primarily to hear from you, not only to speak to you but also to listen to you. I have just returned from Los Angeles to South America, and the feeling of living under a volcano is now very strong there, as it is becoming more so in every part of the world.

Defining Feminism

In this context, feminism is extremely important, although I would rush to explain what I mean by feminism. It’s crucial because, over the last few decades, feminisms have been created, particularly by institutions like the United Nations. A kind of institutional state feminism has emerged that is very much distorted from what feminism originally meant—its original drive and intent. This was not merely to improve women’s conditions or, far less so, to achieve equality with men, who, in the majority, are also exploited. Equality was not only with men but aimed to bring about a societal change.

The Historical Role of Feminism

In the early 70s, there was a sense that feminism was a movement to change society from the bottom up, which was very well understood by institutions—not by the left—but by institutions. Governments were eager to grasp the movement’s potential, organizing to co-opt it and use it to integrate women into a new phase of capitalist development.

So, it’s important to define what we mean by feminism. To me, feminism, in its essence, is a movement motivated by the experiences of women in society regarding the work of reproduction, daily life, and the struggle over this work—the struggle against the devaluation of this work and the revaluation of reproductive work, which is essentially the revaluation of life.

The Devaluation of Reproductive Work

When you devalue the activities that sustain our lives on a day-to-day basis—such as giving birth, raising children, caring for the sick and elderly, and engaging in the myriad activities necessary for our subsistence, both physically and intellectually—then you devalue life. This, in fact, is the essence of a capitalist society. I believe that feminism, for me and many other women, has been a crucial lens through which to understand not just the condition of women but also the workings of the capitalist system.

To understand that this is a system that, in order to perpetuate itself—to sustain its class of accumulation—must devalue what is most essential for the reproduction of human beings. Additionally, it is a system that must continuously create and accumulate divisions and differences among people.

The Intersection of Feminism and Capitalism

I come from a feminist perspective, representing a population of women who, in various ways, have been at the bottom of the social scale and, in that sense, have shared much common ground with people discriminated against based on race and ethnicity. From that experience and history, we have observed that capitalism cannot sustain itself without a continuous process of destruction—destroying the means of reproduction—thus rendering people vulnerable to the most intense forms of exploitation.

The accumulation of differences and divisions is key. Capitalism, far from being a generator of wealth, is a constant producer of scarcity—a constant creation of hierarchies, a production of people without rights, a production of individuals whose super-exploitation must be justified by ideologies that make them guilty for their situation.

Sexism as a Structural Requirement of Capitalism

We understand that sexism is a structural requisite of capitalist society. This requirement exists because capitalism needs various forms of inequality—this is why it projects itself as democratic, based on supposed equal exchange. In reality, it must continually create forms of labour and social relations that exist outside of any contract—that are, in fact, very akin to formal slavery.

Today, we see that slavery is back. We are discussing it now, and official statistics indicate that about 30 million people are currently in slavery worldwide. Even outside of formal slavery, many social relations and activities come very close to it.

The Daily Struggles of Women

I think that feminism, viewed from the standpoint of reproduction, has been immensely important in observing that the devastation and destruction of the means of reproduction, the creation of permanent warfare that we see today, and the continual establishment of divisions are not accidental. They are not merely a phase of capitalist development to be overcome, but rather, they are structural characteristics of the system—essentials for its sustained operation.

I stress this because when we speak of our resistance—particularly of the struggles we engage in, especially in women’s struggles—we must conclude that it is crucial in how we organize. We need to create the foundations for a new society. In other words, whatever struggle we engage in must contain the seeds for the creation of a new society.

We cannot continue to cling to the hope that somehow, somewhere, the system will become more humanitarian. This, I believe, shifts our perspective. We need to change our viewpoint. We must organize our lives and our resistance in direct response to the ongoing challenges to our ability to reproduce ourselves.

I want to mention here, given that we are in a university setting, how significant it is for university populations. One of the key elements of the policies and reorganization of daily life brought about by this capitalist development has also been the commercialization of knowledge. This has created— as Jessie mentioned before—a whole population of students who now must become literally enslaved to the banks in order to access an educational process that enables them to become knowledge producers.

A Promise for Genuine Change

This is a crucial aspect of thinking about the breadth of our struggles. Given this premise, I believe it’s also important to acknowledge that today, the feminist movement—understood as a movement for the revaluation of reproductive work and reproduction in the broadest sense—holds significant promise for genuine change.

I want to explain what I mean by that. Over the last four decades—from the 70s to the present—reproduction has been transformed and expanded. Initially, in the 70s, we thought of reproduction mostly in terms of procreation and housework. I was involved in an international campaign in the 70s advocating for wages for housework, which largely shaped our understanding of the organization of reproduction.

However, this concept has expanded over time. Today, when we think of reproduction, especially looking at how women and families are organizing globally, we see that reproduction now encompasses many more meanings. It now implies care for the environment. You cannot think of reproducing life without being concerned about and engaged with the protection of nature, the waters, and the forests. In much of Latin America and Africa in particular, but also here in England, women are at the forefront of these struggles.

Women’s Role in Environmental Struggles

I have recently conducted research on the movement against fracking in Europe, and I have observed that, for instance, in England—though I’m unsure about Scotland—women are leading the struggle against fracking. In fact, most local struggles are spearheaded by women. This reality holds true in many parts of the world—the struggles for land defense, against deforestation, for the protection of waters, and efforts to maintain control over genetic resources and seeds; the creation of seed banks, for example, is largely led by women.

There is a continuity between the reproduction of life and caring for the environment. Women are the ones who suffer most when waters are poisoned or when oil companies intrude into their communities, understanding their role in reproducing their communities. These destructive activities threaten the very existence of their communities.

The Recovery of Knowledge Systems

Simultaneously, reproduction also encompasses the conservation and recovery of knowledge—especially ancient systems of knowledge. Much knowledge is being destroyed. Capitalism monetizes not just the computer, the iPhone, and all technologies. In recent years, I have critiqued that monetization and its seductive nature, pointing out that much of the technology we perceive as empowering and an expression of the enrichment capitalism brings is often based on the destruction of communal resources and the exploitation of many people’s commons.

I am not against technology, but I criticize the often artificial perspective with which technology is treated. Moreover, we must acknowledge that along with the production of these new technologies, we also see the destruction of many knowledge systems.

Each time a community, a forest, or a whole living environment is destroyed, we lose not only those environments but also the knowledge systems people developed in relation to them. For example, in the past, many communities in Africa didn’t rely on buying pills for malaria because they knew the herbs that could cure mosquito bites. Sadly, those herbs are disappearing. The plants and roots—those knowledge systems that provided direct access to healing—have been lost due to the shrinking forests and the destruction of wetlands, among other causes.

Reconstructing Memory as a Social Endeavor

Today, we have a movement of women, as I’ve observed in many parts of the world—particularly in Latin America—and I am treating this as a terrain of struggle. The struggle for reproduction is evolving in ways we certainly did not anticipate in the 1970s.

Reconstructing memory now involves understanding that reconnecting with collective memory is itself a social endeavor. Living in a completely abstract environment can be disempowering—this is something urban planners, politicians, and authorities have learned well in the United States. The creation of architecture and urban planning systematically erases reminders of the past, distilling power structures that showcase the inevitability of their rule.

Thus, the question of rebuilding collective memory and harnessing the power of memory is becoming an essential domain of struggle—a crucial terrain of struggle surrounding reproduction. To understand and connect oneself to the world and to the spirits of those who came before you grants tremendous strength. It allows you to see that you are part of something larger than your individual life.

The Power of Collective Memory

This connection empowers you because when you view your life as an isolated entity, you lose the sense of power that comes from your relationship with your mother and your collective history. To rebuild that structure of memories that connects you to a place—the process of making a place a living organism that communicates with you—provides a foundation for resistance.

As I mentioned in an article in “Rethinking the World,” the book I recently published, women I spoke to in Mexico who have been actively involved in maintaining communal relations observed that in regions where people have a deeper knowledge of the past and connect with earlier generations, their capacity for resistance is significantly stronger.

The Historical Context of Witch Hunts

This is one of the reasons I believe it is crucial to revisit the history of capitalism and reconstruct the history of women, particularly the history of witch hunts. Scotland has been a major site of witch hunting, and one of my hopes in giving talks is to inspire new generations—particularly women—to reconnect with this history. I believe that understanding that history sheds considerable light on what’s happening in the present.

You know, for me, it was certainly a revelation at the time in the 70s and 80s, when I was trying to make sense of the world—when it was time to make sense, you know. You have this desire, this tool; you have this desire to break out of being a woman raised in a very patriarchal way. And then you say, “Oh my God, what is this revolting system? What is this society?”

Confronting Cruelty in History

For me to do that work—to see the development and to engage with that story—to confront the fact that, at one point in the story of the development of capitalism, hundreds of thousands of women were publicly burned after being tortured to death, you know, in the squares of Europe—in public. Imagine what it would be today, you know, to have one woman burned in a square in front of everybody, with the authorities telling you, “Come, come, come to see. You have to come to see. They’re burning the witch,” right?

Consider what it meant that there was a time when a much smaller population—a much, much smaller population—had, perhaps, year after year, sometimes one, two, three, or four women being burned. Think of the terror that women were subjected to. Then you go and see what was the process that led to a woman being named a witch and brought to the execution site to be burned in the square. This had a profound effect on my understanding of what a capitalist society is and also a profound effect on understanding the kind of cruelty that has become institutionalized among the ruling classes, in the political authorities.

Contemporary Witch Hunts

Part of my work today, part of my political work, is also to try to tell and inspire others, you know, to do their work. For instance, I have a project now with women in Mexico that is the most advanced, where we begin to do the work. We start by visiting areas where executions took place to see what is happening in those areas today.

What we discovered is very, very interesting: we found that, in fact, today, there is tourism being generated from the burning of the witches. They’re actually selling merchandise—they’re making money. You can go, for example, to the border between the Bay of Biscay country, at the border between Spain and France, and on both sides of the border, you will see shops full of witch-themed items, right, with the teeth out of their mouths, the satanic symbols—all for €30. You can take home a cup or a doll. You have all these dolls, you know, with brooms and big hats—it’s like a joke.

The Distortion of Witch History

The big joke is a big joke. And the children go with little brooms in their hands. We went to the shops and told the women who sell these things—because it’s mostly women—“Hey, you know what? These women were burned. These women were tortured to death.” If you read the history, you would be so upset. Imagine selling puppets or dolls of people dressed in the uniform of a guard. Imagine that connection not being made. It’s acceptable to sell the image of the witch. Everybody would be outraged if, in some place, you know, on a street near you, there was a shop selling for €3 a figure dressed in the uniform of a guard. Would you agree that they would be upset? Yet nobody is thinking about how much the story of the witches has been distorted—how much it has been hidden and twisted.

How much the blood and suffering of thousands of women have been forgotten, except by a few historians. So, one of my jobs is, in fact, basically to say, “No, we have to go back.” They say, you know, “What is not remembered will be repeated.” And today, it is being repeated in many parts of the world—like in Africa and India, where you find a resurgence of witch hunts; there are renewed charges brought against women, and even public executions of women accused of witchcraft.

Understanding Contemporary Witch Hunts

I think it’s very important to understand that today’s witch hunts, which have come to me as incredible surprises and pains, are not disconnected from the returns of the past. Because, like the returns of the 16th and 17th centuries, today they are very much tied to the expansion of capitalist relations and the fact that this expansion requires the destruction of many forms of reproduction and extends control of the state and capital over the bodies of women.

So, there’s no coincidence today in so many African countries, in India, and now it’s happening in Papua New Guinea. You have again the persecution of witches returning. And then, all over the world, there are invasions by Evangelical sects, Pentecostal sects, and others that have now taken hold of the narrative—a satanic view of poverty today. Not because of capitalism or any structural issues of capitalism, but because Satan is out in the world. And there are people in the community who are, in fact, doing evil deeds.

As in the 16th century, we see a kind of propaganda emerging at moments when people have been attacked. The attacks are directly on the means of production, right? They sow suspicion among the people, weakening their resistance, making them fight against each other, and concentrating their anger against the witches, right?

The Role of Women’s Struggles

So, I want to conclude by saying that it is very important, the work that so many women are doing now across the world. Beyond the question of reproduction, which truly encompasses a broad range of struggles—struggles over procreation, child-rearing, and the organization of daily reproductive work—the organization of reproductive work is becoming, in many areas, more cooperative. We see that breaking out of the isolation in which housework and reproductive work have traditionally been done is crucial not only for guaranteeing our survival but also for strengthening our struggle.

This is, in fact, beginning to happen. We see in many areas, particularly among people who have been displaced from their communities, forced to migrate to towns. You find it, for instance, in places like the peripheries of Argentina, Chile, or Peru. You begin to see new forms of reproductive work being organized that are far more cooperative. For example, popular kitchens and community gardens—you have examples in Colombia. The communitarian mothers, you know, women are now taking care of many children who are on the streets, but they are beginning to take responsibility for those children.

A New Community of Reproductive Work

So, there is now a movement, what I would call the community of reproductive work. And to conclude, I would say that this is very important not only for our survival—not only for the survival of the many people whose lives are immediately put in danger by the expansion of capitalism—but also for the struggle. You cannot build organizations, struggles, or forms of resistance over a long period unless you create a reproductive basis for it.

In other words, a change in the way we reproduce ourselves is important not only for survival but also for our struggles. Struggles need a reproductive structure. They need the creation of forms of relations that bring people together based on collective work, that fosters forms of solidarity, collective solidarity, and, above all, affective relations.

Emotional Power in Women’s Organizations

I think one of the great powers of women’s organizations is the fact that they are increasingly based on affectivity, emotional power, and a sense of solidarity that comes from working together; that comes from putting each other’s lives in common. Thank you very much.

Opening the Floor for Discussion

Good, so now we have a good amount of time for questions and comments. One thing I know is important is that this is also an opportunity for us to share tactics and to discuss what might be happening in the city that could be forms of reproduction and sustaining a sense of revolutionary moments or the revolution of everyday life. So people are very welcome to think about that.

Question: Reflections on Student Exploitation

Some questions I had to start, actually, revolve around this idea of students as being the site of capitalist exploitation. As a teacher in education, it’s something I have felt strongly about after working in education for the last 10 years in terms of how students approach their education. They seem to barter their own lives for access to housing or have to work full-time jobs while also pursuing their education.

This wasn’t something I was exposed to when I ended up in education—at this brief moment when they suspended fees for a short period—like two weeks of prosperity that we had. One of the things I found quite inspiring about your talk today was that I had previously made a link between education and the wages for housework movement in the 1970s. Perhaps one of the reasons why students are so exploited is that they are considered a resource as consumers. Their labour is seen as a consumer resource for capitalism.

Taking inspiration from the 1970s and the housework movement, perhaps students could start to think of themselves as workers rather than consumers, as earning wages for education rather than simply paying into the educational system—that perhaps wages for students could be a radical movement for change. Well, we had that. Actually, we had that in the 70s. I think if they actually— I have a book; I didn’t bring it, but I can send it to anyone interested.

The History of Wages for Students

I think it’s very interesting for those involved in education. One book is about wages for students in the 70s; that was one of the demands in Italy, where the student movement fought for the “pre-salario,” or pre-wage. The pre-wage was based on the idea that we go to school, we go to university, not necessarily because we want to go to university, as we can also produce knowledge and learn outside of the institution, but because they tell us that unless we have a degree, unless we have a certificate, we will be sleeping on the streets for the rest of our lives.

In fact, that kind of argument has become more prominent today. Almost every politician will say, “Oh, unemployment is because we don’t have a qualified workforce,” etc., etc. So they say to you, “Yes, we have to have a qualified workforce.” However, today….whereas in the 70s, the state, and here is a very crucial question to consider—why is it that in the 70s, the United States was still, perhaps, competing with the Soviet Union?

In any case, until the 70s, they still recognized the importance of education for the system—that a more educated, formally educated workforce was better for productivity, producing forms of consent, right? Then, an important change occurred, likely coupled with the response to student struggles, and one of the responses was to make them work in a way that left them no time for thinking.

The Burden of Student Debt

Show of work, work, work, work, work! In fact, that is what is happening now. Instead of subsidies to education, you have the introduction of fees. So where until the late 70s, in the United States, education and other forms of education were heavily subsidized by the state, in ’76 in New York, this ended; open admissions ceased, and they introduced fees.

And today, the fees are so high that the average student in the U.S. graduates with $30,000 to $40,000 in debt, and most will not be able to obtain jobs enabling them to pay it off. They will carry that debt for a long, long time. It’s the only debt in the United States that one cannot discharge through bankruptcy.

If you die and your parents felt the misfortune of signing the contract with the bank or government, they will have to pay for you. We already have a situation where many seniors are losing their social security because they signed the contract, and their children could not pay, and now the government is taking away their social pensions. This is what is happening, right? There has been a struggle—it’s a struggle, you know.

The Role of Commercialization in Education

I’m saying now the struggle is against that, and it’s crucial because the struggle against that is also a struggle against the commercialization of education. Education is now seen as a commodity. Universities are selling a good, right? This has a very, very significant impact on the quality of the knowledge produced.

I can say much more; I taught for many years. Now, I’m happily retired, but I was one of the last who could “retire” with a pension—okay, today it’s becoming more and more difficult for teachers to retire comfortably.

The Significance of Student Conditions

So the state of students is very, very important, as it represents a struggle—not only a struggle against solitude but also a struggle concerning the quality of education. It involves the conditions of that knowledge production. Because when knowledge becomes a commodity, the content is deeply affected, and we see that every day.

I was discussing two books: one about wages for students produced in the United States related to student loans, and another called “The Debt Resistors Manual” – It’s a handbook about resistance to debt, examining the politics surrounding the issue. Why? Because the struggle against debt constitutes a form of exploitation, but the struggle against debt is much more difficult than the struggle for wages.

The Isolation of Debt

When you are in a wage struggle, you’re part of a collective. The fact that you’re exploited means you are a worker, there’s a clear relationship with the boss—that’s a direct exploitative relationship, and you belong to a group that shares a collective sense.

However, when you’re dealing with debt, that is very different. It’s still exploitative because you have to work much more to pay your debt, but at the same time, it becomes very isolating. First of all, people feel guilty; they think, “Oh, this is my fault.”

We learned a lot from struggles in the U.S., from the student movements against debt, right? We discovered that people don’t come forward because they feel guilty. When you have debt, you immediately think, “This is my fault.” Secondly, it’s just you and the bank; you face the debt in isolation. Even if you know others have debt, you don’t have the same collective atmosphere present in a wage struggle.

The Political Dimension of Debt

We found that it has a significant political dimension, and it is likely being used precisely because it’s much more difficult to fight against it. Now, almost everyone has debt; you must indent yourself for healthcare due to reductions in subsidies. Many people are accumulating debt. For instance, in the United States, we are now learning that the largest number of people with student loan debt falls among working women.

I say “working women” because I think that term implies women outside the home, but I argue that women work in the home as well, right? So women work outside the home, and even if they hold two jobs, they still don’t earn enough; the majority does not achieve economic self-sufficiency, right?

The Cycle of Debt and Consumerism

So what do they do? As soon as they can, they take a loan. The majority of women with jobs outside the home end up accruing more and more debt. And now there are companies offering “payday loans.” I don’t know if you have them here, but you must have them. Payday loans refer to loans given on the day you receive your paycheck; you borrow against your salary for payday.

This situation clearly undermines the idea of liberation through labour. We were led to believe that women would become emancipated through employment, but that’s true for only a minority.

Disempowerment and Daily Life

There are many ongoing issues; increasingly, people are trapped by having to go to stores daily. Credit cards contribute to the politics of debt, now used as a tool for subordination. On the one hand, you have this, and on the other side, there is a movement.

As part of the student movement against debt, there has also been a study about what is needed for the anti-debt movement. We have examined movements against debt; for example, in Mexico, there was a significant movement in the 1990s. In Central America, communities practiced collective strategies. If you have a cyclic community, you can begin to advocate, “Okay, we will pay what we think is fair.”

Strategies for Collective Resistance

This is one strategy: “We pay what we believe is right.” The community collectively agrees on this. If you have that kind of solidarity, like in Italy in the 70s, you also had a self-reduction movement.

Those of you from my generation may remember that in Italy there was a self-reduction movement. It worked precisely in this way—people collectively refused to pay more than 10% of their transportation or electricity bills by deciding within their community what they could furnish.

This was very important. And that’s why so much of the struggle revolves around this as well. The reproductive structure we need is to create a cohesive social fabric, an environment where people have relationships with each other—where the reproduction of life and the struggle are interlinked.

The Impact of Separation in Activism

This has been a vital contribution of women’s studies—to recognize that the problem with many male-dominated organizations was precisely this separation: here you have your daily life, your reproduction, and there you have activism—so you go to the square, waving red flags and participating in rallies, and then you go home where your partner has dinner ready, right?

This is why, in the 60s, we said there was never an actual general strike when the men went on strike; it was dubbed a general strike, while the women stayed home preparing dinner, right?

Reimagining Resistance as Defense

Thus, it’s essential not to separate the reproduction of daily life but instead to create transformations in production that support the struggle, fostering relationships that create effective organization with a new social fabric—a new community. This matters significantly, where it occurs, as people are much more able to resist and defend what they have.

“Resisting” is often considered solely negative, right? There’s now a significant resistance to label action as merely “resist,” right? It’s more crucial to affirm “defend” because resistance appears only negative and does not capture the idea that we have something valuable that we want to protect, right? That was what I was trying to express regarding the importance of weaving the community together.

Discussion and Questions

There—hi, thanks very much. I heard very clearly what you had to say about effective relationships and the connection between those and collective solidarity and resistance. However, I also think that affect plays a major part in much political discourse right now—discourse that often produces alienation, individualization, and atomization, right?

I am just wondering if there’s anything you could say to help people like me think about the relationship you might draw between affect, aesthetics, artistic practices, structures, and the production of political subjectivity, agency, and will. Thank you so much.

The Historical Acknowledgment of Witch Hunts

Welcome back. I am very grateful for the work you’ve done on the history of witch burning, and as you know, Edinburgh is somewhat of a capital of that history. Annually, on the Castle esplanade, we have the military tattoo, and as far as I am aware, there is one very small fountain monument to the many women who were burned as witches there. It’s not functioning, and you can’t—it’s also very ambivalent in its significance.

I wonder what you think is appropriate justice and acknowledgment for the many hundreds—indeed, hundreds—of individuals, not all named, who were publicly executed in Edinburgh. On that site, which is still considered a place of military display, what would be appropriate for the city of Edinburgh to show some kind of acknowledgment and, dare I say, reparation? What would that be?

Question: The Limits of Commemoration

Thank you for your talk and for your books and articles. You speak about [speaking inaudible]… and it’s very, very insightful regarding art. I’m not completely sure I understood the question correctly, but I believe that the issue of art and aesthetics is extremely important today—really crucial. I was surprised, in fact, that again I am discussing the United States, as this is the landscape for most artists. Many artists have become interested in the issue of reproduction, particularly some of the work that we did and are doing concerning the kind of oppression, for instance, that women have been subjected to as houseworkers by the state.

Every time they wanted to fight for their rights—artists, for example, have come forward and said, “You know, we now identify with our wives because when we demand to be paid for the work that we do, we are told, ‘Oh, you know, that’s your reward—you want to get paid,’ right?” It’s very interesting that as part of the attack on production that I’ve been discussing—the extension of unpaid labour—it’s crucial to recognize this. You know, it is very, very important because that is why now students are undertaking numerous hours of unpaid labour under the guise of internships. This is extending to secondary schools; now, high school students are doing unpaid work. Full-time workers are being laid off because companies know that schools provide a readily available labour force, right?

The Dual Role of Artists

On the other side, artists are now serving as the vanguard for the state. When a new neighbourhood needs to undergo gentrification, that reflects the other side, right? Art is now in a very, very difficult position because, on one hand, artists are being pushed and coerced, and on the other hand, they are being utilized. Right? So how do we organize the struggle around that? In the United States, we are beginning to expose this situation. They are calling it “wage” issues, for instance; there are artists who are refusing this alternative and are creating ways to resist, right?

That is also very important because, as I mentioned regarding students, the commercialization of education and knowledge is, in fact, a significant part of the destruction of the commons. The same goes for art because art is crucial for the right—it has always been, right? One can measure the effectiveness of the left by the kinds of art it produces or the songs it creates, for instance. Music and art are, I think, vitally important because they really communicate in ways that words can only express to a limited extent.

Navigating Collective Isolation

So I believe this struggle is now taking place, and it is crucial to emerge from isolation. I think this is a current issue that reflects the political dimension of the relationship between institutions, the arts, and students, which has resulted in competition and isolation. Yes, if you can struggle, you can create, and so you begin to develop a relationship with the world that is immensely discouraging because, now, you find yourself isolated in this battle alone, right?

I think joining with people and beginning to look at it in a collective way, while addressing the kind of blackmail that is taking place in terms of all art—you know, it’s important. I know that I don’t have any of this as a guarantee, right? Of course not, but it’s a step; it’s an important step.

The Question of Care and Acknowledgment

The second question—oh, what it means—well, you know, nothing can repair what was done, but the worst thing is those little classes. They are better than nothing, but they aren’t enough; it’s just not sufficient. I think a good beginning would be if, for example, women or anyone could come and make that memory living—read the story.

Read the story of what happened to so-and-so, what happened to Elizabeth, to all these women who were— I don’t think that people really—very few people, unless they have read it and spent time with it—have an idea of what those women went through. Saying that they were hanged or tortured or burned doesn’t suffice. It’s only a very abstract way; you know, you have to read the story, to understand how she was taken out of the house, how she was stripped naked.

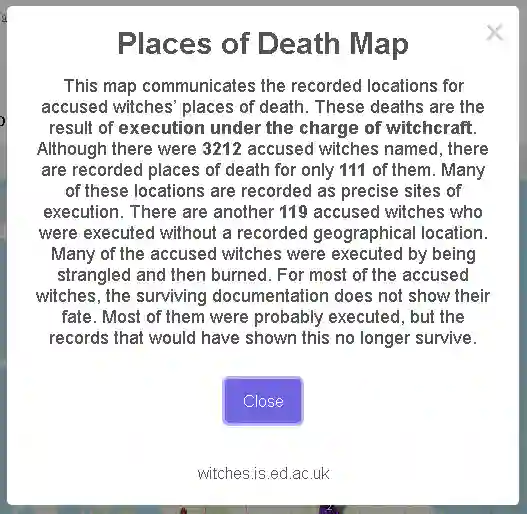

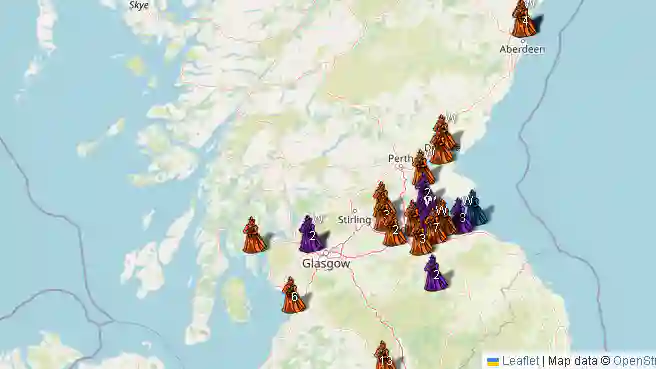

Website dedicated to showing the murders which took place in Scotland:

The Physical Reality of Historical Trauma

Imagine being in a dungeon surrounded by men; imagine knowing that you will not go out except to be burned alive. Imagine how that must sink into your body—the horror that those women went through—and then being spread on a table with someone poking and torturing you with long needles in every part of your body after they have shaved your area so they could probe even in your vagina to look for the mark of the devil. How can you do justice?

But I think if people understood—if people, for the moment, could sit in their flesh and imagine what it must have been like to be one of those women, right? To go through this experience—and that this was a mass experience: this was the authorities, this was the church, this was your church session, this was your government, and these were the people on the ship, in many ways.

The Role of the Ruling Classes

The ruling classes came together. I think that would be the beginning of reparation—not allowing the memory to disappear. Right? To have the voice—to make it, to me, one of my tasks—to make those women present—to bring them here so that they are recognized. I was thinking of the isolation—what it must have meant to be alone in those dungeons, and then knowing that they put something in your mouth and burned it. To give them voice, to make them present among us—you know, I think that’s important.

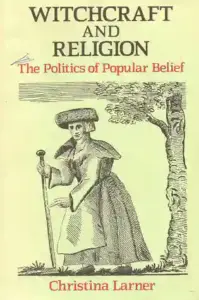

To read more about the history of the witch trials in Scotland a major information source can be found in the books of Christina Larner, for many one of the foremost authorities on this dark past which continues in the times we live in. Here is Alan Macfarlane’s preface to ‘Witchcraft and Religion;

The Politics of Popular Belief’ by Christina Larner.

“At the time of her tragic death at the age of 49 in April 1983, Christina (Kirsty) Larner had already established her scholarly reputation in a number of ways. She was the foremost expert on the history of witchcraft in Scotland. She was thought to be one of the most important social historians of Scotland. Her work was one of the most interesting examples in the cross-disciplinary field of historical sociology.

Finally, she had contributed significantly to legal history and archival history through her study of Scottish records and court processes. All this had been established on the basis of one book, Enemies of God, The Witch-hunt in Scotland, published in 1981, a duplicated Source-Book of Scottish Witchcraft compiled with Christopher Lee and Hugh McLachlan (Glasgow, 1977) a number of articles, unpublished lectures and an unpublished doctoral thesis.

Dr Larner’s work is important at both a descriptive and a theoretical level. Descriptively, we now have a far better idea of the dimensions and nature of Scottish witchcraft prosecutions and beliefs. By the use of the original legal records Dr Larner was able to show where witchcraft prosecutions occurred (almost exclusively in the lowland regions and, particularly, near Edinburgh) and when they occurred (1560-1700, with peaks in 1591, 1597, 1629 and several between 1649 and 1662). She was able to show who were the accused (mainly middle-aged and old women) and the process of the accusations. The differences and the similarities between Scottish, English and Continental witchcraft were illuminated. For the first time, the legal processes behind the prosecutions were laid bare. /\ll of these themes are pursued in further detail in essays which form the first five chapters of this volume.

One of the striking features of Dr Larner’s work is a sceptical attitude towards simple and universal explanations. Yet, in the last chapter of Enemies of God, tentative suggestions arc made concerning the necessary, if not sufficient, causes of the witchhunt. The preconditions are a peasant economy, a witch-believing peasantry, and an active belief in the Devil among the educated, hour more proximate causes explain the specific timing of witchhunts.

First, was a judicial revolution, consisting of a shift from ‘restorative justice’ (where the case is brought by the injured) to ‘retributive justice’ (where it is brought by the state), applying general and abstract standards. Second, there was the rapid development of printing and literacy. Third, what is termed the ‘Christianization of the peasantry’, that is to say the move from a largely animistic and ritual world to one where personal salvation and Christian belief became predominant.

Finally, there was the rise of the Christian nation state. The witch-hunts coincided exactly with the period of the Godly state, when Christianity became the official ideology of the new-born nation state. The fruitful ideas hinted at towards the end of Enemies of God became central themes in the Gifford lectures which constitute the second half of this volume. Although these factors do not work particularly well in explaining English witchcraft prosecutions, they throw a great deal of light on the horrendous mass witch-hunts on the Continent.

One of the most interesting features of Dr Larner’s subject matter, as she herself notes, is the way in which Scotland lies at the mid-point between English and Continental cultures. Roman law and the inquisitorial process, the remains of the Celtic clan structure and another language, gave Scotland many similarities with parts of Europe, that are reflected in the pattern of witch-hunting. Yet its early conquest by Norman barons from the south and close contacts with England made it share many of the features of English society. It thus provides an excellent test case for seeing the similarities and differences between parts of Europe in the past. A centra) and repeated emphasis in Dr Larner’s discussion is the way in which neither the English nor the Continental model of witchcraft works properly for Scotland.

In England, the prosecutions were almost totally concerned with ‘maleficium’, causing harm to one’s neighbours, and little concerned with Devil worship, covens or heresy. On the Continent, though many trials started with the former, once they reached the courts and leading questions and torture were applied, they were turned into heresy trials, concerned principally with the Satanic compact. The two types were strongly differentiated. Through a minute investigation of both the local and the central records, Dr Larner is able to show that Scotland fell between these two extremes. Maleficium was of interest to the high authorities, just as the Satanic compact was of concern to villagers.

The study ot witchcraft is both important and difficult. Important because such beliefs lie at the precise intersection of religion, law, economics and family-life. Thus an understanding of this phenomenon leads to an understanding of much else besides. Because of this. Dr Larner’s learned and thorough work on Scottish witchcraft illustrates so much else about early Scotland. It is for this reason that the subject is so difficult, for to penetrate far requires that a scholar become knowledgeable in all these fields. Dr Larner was acquiring this knowledge and adding to it that comparative framework provided by sociology and social anthropology. She was never prepared to accept easy answers and the tone of the following essays and lectures reveals the pugnacious, enquiring mind that endeared her to so many. In the notes she made during her last illness, she concludes a section thus: ‘So what should the communicating sociologist aim at? There are three things she can do for the historian:

- Demonstrate to historians what their own theoretical assumptions are.

- Produce historical material which illuminates and uses sociological theory.

- Demonstrate the relationship between social theory and historical scholarship.

All this to be done in Times English.’ The reader will have to decide how far Dr Larner has succeeded but there is no doubt that she always wrote with clarity and a refreshing absence of jargon or mystification. As Norman Cohn wrote in the foreword to Enemies of God, ‘Where hitherto our view has been blocked by a seemingly impenetrable mass of undergrowth, a path has been hacked out. A wide vista stands revealed. From now on it can surely never be lost to view.’ These essays and lectures extend and broaden that path.”

The Complexity of Capitalism

In response to your question, I didn’t mean to suggest that the care could be enough, right? I didn’t suggest that it could be enough, of course. And I spoke of the feminist movement not assuming—I mean, capitalism is a many-headed beast. It’s a many-headed beast, right? They call it hyper-capitalism—has many heads. So the struggle against capitalism has many, many forms, and I can see an anti-capitalist movement with many components, right? People fighting to defend the forest, women fighting against the criminalization of pregnant women, which is happening today in the United States. There is a whole criminalization of pregnancy among women, which is scary.

The Intersection of Various Struggles

People are fighting around education against debt. I think the challenge is how these movements come together. If these movements can find common ground, right? So the answer is not only that, but what I think is that the feminist movement, and women’s struggle in general—and I say that because many do not recognize themselves as feminists—probably many women struggling today in many parts of the world, if they hear the word “feminist,” might say, “I’m not a feminist.” They might feel a certain way, but I would consider it. I give a particular meaning to feminism, but what I wanted to stress was the importance of reproduction for the continuity of struggle and the organization of everyday struggle.

Everyday Struggles and the Path Forward

A struggle is not only those moments of great confrontation, but it’s also about the everyday. It’s also about how we transform every day because it’s every day that we are most often isolated from each other. So transforming the everyday organization of reproduction informs the breaking of isolation, etc. I think it’s very important. So I wasn’t thinking in terms of replacement; I was thinking in terms of the creation of a fabric—a social fabric capable of sustaining a long-term struggle against capitalism. It’s going to be a long fight, yeah.

Question: Acknowledging Differences in Education Costs

So, question, comment? Yes, oh, thank you for your talk. I’m 70 years old, and I was a student in France in Paris in May 1968 for feminism. But I think you’re right about the students and the problem with loans. It may be true in the USA, and it may be true here also, but for example, it’s not true in France at all. In France, when you are studying at a state university, you can study for engineering or even at Polytechnics, and you only pay €200 a year in fees. So you see, it’s definitely lower-cost for students.

The Choices of Educational Systems

So it could be absolutely true, but it’s a choice of the state. The U.S. made another choice; they made education costly. Yes, that’s important too when you look at different parts of the world. Europe is, in many ways, different; even in Germany and Italy, it’s different. Another thing is that you were relating feminism, the problem of feminism with capitalism, which is absolutely true. But when you relate that to the right to the past—even in very, very old days, it’s still true.

The Role of Religion and Gender Inequality

Because you didn’t mention the problem of religions, and the issue is not only with the Christian religion but with some other religions where men are just keeping half of their population in a kind of inferior state, in slavery. So I think it’s maybe half of the world that is doing that, and that’s still a problem. Because when you are a woman in these kinds of countries, what can you do? What do you mean? Well, you have no power; you have to fight your… to fight the men and to fight the system, and that’s very, very difficult.

Navigating Colonial Narratives

I okay, all right, I think… I okay, yes, yes, and there was… One—hi, thank you so much for being so forthright. This is incredible. I wanted to sort of come back to the idea about reconnecting with and reproducing histories and thought, and wondering how, as radical leftists, you navigate this terrain when the right and the nominal left are engaging in these projects, which are basically just colonial nostalgia. How do we enter that terrain—that kind of project—and not reproduce the kinds of narratives that they’re creating? You know, for instance, there’s a supposedly left-wing narrative in the U.K. around nostalgia for the NHS, but that’s never discussed in the context of the fact that this was created because of Cold War dissent and funded with the proceeds of colonialism.

How do we navigate that history when that project’s already underway, and the narrative is already so entrenched? Okay. Yeah, okay. Is there any other questions? I’ll take that one too, and then… okay, I’ll take that one, and then this one and… then that microphone.

Disempowerment in Daily Life

I was thinking more about how disempowered we feel since, you know, how capitalism has made us so disempowered in terms of day-to-day life. We feel like we need to go to the shops to feed ourselves. We need to rely on the council to take care of our waste disposal and provide our water. I think, especially with the Allan religions and witchcraft in particular, we were so empowered to not only provide everything for ourselves but also to have a spiritual connection, which is really linked to this caring reproduction, you know, like caring for our community, our children, and nature and the ecosystem.

I feel like there’s so much in my head about how we can move forward because that’s the hardest thing. When you’re spiritually disempowered, you just feel overwhelmed and have no way forward. I think we just need to start… with religion.

Question: The Future of Education Accessibility

I want just to go back to the point that you made about charging fees for education. I’m very glad that so far Scotland hasn’t gone down that path, and that Scottish students can still study without paying fees. But I wondered whether you think there is an intention to make education more elitist again. And the real question is: Do you think that the imposition of fees is more likely to exclude women who have other responsibilities? Yes?

The Global Trend of Education Commercialization

So there are some countries that have not introduced fees although I would argue that the commercialization of education is a global trend. I think it’s not the majority, actually. The world has not universally adopted it. But when you look on a global scale, the matter of transforming every form of knowledge—every aspect of everyday life—into a commodity is very, very extensive. So the commodification of body parts, knowledges, and so on; it’s really very extensive, and this is what I’m arguing against.

For example, you know the most basic one—the genetic material of life or culture. You know, the market of genders, the market of seeds, the marketing of children, as well as the marketing of knowledge. Knowledge, too, is now considered a commodity in the dominant neoliberal ideology, you know? And I think it’s part of the struggle over education, too. It is very important because the moment that you introduce fees, you basically prevent people from accessing education.

Impact of Fees on Education

I have students, for example, in the States who come to class and fall asleep. You sit down, and the next thing you know, they’re sleeping. You ask, “Why are you coming to school?” And they’ll say, “Well, I worked until midnight last night.” You respond, “Well, why don’t you just not come?” They’ll answer, “That’s the only way I can survive.” So the space they would have had in the ’60s, where you could attend classes and read books beyond those assigned in class, is now far less available.

Additionally, the social life on campuses has diminished. People must work, or they can’t afford to live communally because it costs money. This is a general issue, not only in the United States but also in Latin America and Europe. So what is happening in the States is vital to observe because it might reflect future trends; it’s already present on many campuses.

The Implications of Maternal Rights

The other question of religion, I think, is very important. But when I speak of wealth and capitalism, people often say, “What about religion?” And I say, “Well, you know, actually in most of Europe, the witch hunts began at the time they were instituted by the state. They were instituted by the king, by the local government, etc. It was the state authority that initiated them—and in the period after the early 16th century, religion became less important in many parts of Europe due to the schism between Catholicism and Protestantism.

However, here it was very significant; religion was part of the state. That’s really the main point I want to make: religion has always been part of the dominant power and continues to be. For example, you can see it clearly in the way the Catholic Church on one side and Protestant Evangelical sects on the other are both circumnavigating the globe. They began doing that particularly with the onset of the neoliberal phase, and they are cooperating to impose the dominant policies—whether it is the Pope, the Vatican coming down very heavily against any form of abortion, or any attempts for women to control their bodies, as they’ve done recently in Latin America.

Religious Institutions and Patriarchy

In Argentina, for instance, there was a huge mobilization of hundreds of thousands of women in the streets fighting for abortion rights. And the Vatican organized massive counter-demonstrations, right, with the slogan, “Poor women do not abort.” They claimed, “Abortion is an IMF plot.” They understood that people hate the IMF, and thus they suggested that abortion was an IMF conspiracy, asserting that the IMF doesn’t want the poor to have children, which is probably true. But this is a separate issue.

So, on one hand, you have the Vatican and, on the other hand, the Evangelical sects, who since the early ’90s have spread globally. I’ve seen them in Africa, spreading narratives that if the poor become poorer, it’s due to someone conspiring within your community. They actually have handbooks on how to recognize witches. In their countries, like Ghana, for instance, there is a concentration camp for witches. You can go online; it’s well documented. You can see that there are at least 3,000 women living in camps for those expelled from their communities.

The Revival of Witch Hunts

These sects not only revived the witch hunts but also reinstated the narratives around possession. Now, in Africa, there are exorcists going around different towns, particularly in the Congo and Central Africa, conducting exorcisms on children purportedly possessed by the devil. This is a clear example that these sects, which are now present in all centres of power, like in Ghana, wield significant political influence. They are very pluralistic; they have been financed and organized by many right-wing organizations in the United States, closely tied to the U.S. government.

The Interplay Between Religion and State

When we speak of religion, we should not think of it as separate; historically, the separation of state and religion has been mostly non-existent. Since the 18th century, there has been some appearance of separation, but in terms of interests—and in terms of what it has promoted—you can see this goes back to the French Revolution, where, purportedly, a city and religion were separated from one another. That has been very closely intertwined with…

I come from Italy, and believe me, Italian history demonstrates this clearly…

Okay. Now, regarding the question of colonialism? This is a broad topic. I think it relates to the concept of what is necessary to change—to change society—to change the world. The body politic, right? The way I think about it concerns the relationship between struggle today in the U.S. and the New Deal. The New Deal was the major alternative people are looking at; it guaranteed social contention, unemployment benefits, health care, etc. For much of the left, the alternative to what is happening now is to revert to the New Deal, right?

Rethinking Narratives from the Past

Yet, there’s another side: the New Deal only benefited a certain segment of the population. Most Black workers were excluded from it, right? For instance, domestic work was not included. Even when it was paid, domestic work in the United States was only recognized as labour after 2000, due in large part to the struggle led by immigrant domestic workers who effecting change in the New Deal. Even when domestic workers received payment, they were treated as companions, exemplifying the devaluation of their work.

The Challenge of Nostalgia

So can we be nostalgic for the New Deal? Or can we be nostalgic for a healthcare system that was highly discriminatory? I think the notion at hand is not about returning to the past but truly beginning anew—I see this as important because it links to the question you raised, right? I recognize the significance of fostering new social habits, not only in terms of resisting incoming threats but in terms of initiating and supporting a struggle for appropriation.

Prioritizing Material Conditions for Change

We cannot transform the world unless we change the material conditions in which the majority of people live and unless we take back the means of reproduction. The key issue with the state is that we can ignore the state because it has monopolized not only violence but also wealth. One of the core concerns today in our attempts to change the world is how we can reappropriate the wealth of production and natural resources.

Now more and more of this wealth is being seized and privatized: the destruction of communal property, etc. The privatization of public space—everything. So how do we maintain a process of wide-ranging reappropriation of wealth? I think this is the fundamental question because, to achieve organizational life and social justice, there needs to be a material basis.

The Interconnectedness of Struggles

It must have a material basis that transforms not just the lives of a minority or specific sectors of workers. That’s what we’re discussing. I’m stating that the feminist movement is crucial because it addresses the issue of reproduction; it broadens the parameters of the struggle. When I grew up, it was industrial working-class, the factory work by the communists—they came from communism waving the red flag—but it was always centred around the factory. The factory was always the focal point; that’s where the revolution was.

I go after that. It took me some time to understand it was another world. I think the feminist movement was the first to disrupt the anti-colonial movement, beginning to carve its path, right? By realizing: “No, there’s something else.” The other workers created capitalism, and they became revolutionary. So, this has opened up and expanded the understanding of what we need to change.

The Crucial Role of Material Conditions

This is crucial; however, fundamental to the struggle is the question of material conditions. If we control the Earth, the forest, the water—as is happening because the state now has direct control over the land and our bodies—if we lose that control, escaping further violence and exploitation will become extremely difficult.

The Threat of Environmental Degradation

Because once you have that push—in the push from Monsanto, the car companies, and mining entities, etc.—to push everyone into a series, empty out the seas and lands. The privatization threatens to level the Amazon. Can you imagine? It’s going to level the Amazon! Of course, it will kill the people living there—huge populations, and the women are making a significant fight in the Amazon. The reason there is so much violence against women now, especially in many parts of Latin America, is because they are defending the land, particularly against this complex.

They can see that the moment the land is poisoned, the community dies. Many of the young men in those communities, in fact, support the arrival of these companies—they are unemployed; they’ve endured a long period of joblessness, and for them, a wage represents power. So often, women are victimized, not only by the armies of companies but even by the men in their own communities. Of course, the government paints them as obstacles to progress. That’s a very significant issue.

Understanding Consumerism in Context

Yeah, and, uh, regarding consumerism, yes, yes—it’s very important to see that what we call consumerism is truly a response to impoverishment—not only economic but also emotional, spiritual, and social. Yeah, it’s the kind of… look, people think they enrich their lives, you know, by buying another gadget or piece of clothing, because our lives have already been impoverished.

The Illusion of Capitalist Enrichment

And this is something I think is pertinent: I’ve been working hard to combat the idea that capitalism enriches our lives. It’s like a distraction. Yes, it gives us the illusion of enrichment because we now possess all this technology, right? Certainly, some of this technology may be useful, and some is exceptional, but much of this technology has a double-edged sword; it’s built on the destruction of many communities that isolate people rather than connect them.

The Alienation of Modern Life

We see children addicted to gadgets. If you observe the subway in New York, everyone is glued to their devices; they live a substantial part of their lives with that in their hands. That cannot foster meaningful social interactions. We truly need to be… but I think the objective is not merely an attempt to reclaim what we’ve lost, you know?

I think when you refer to magic… we’re discussing magic today, right? I’ll consider the concept of magic should recognize that, right? You know, magic has become distorted—the notion of what magic entails—and I’m saying that powerful relations among people are magical. Something occurs that you cannot explain in traditional terms, but there is a deeply magical aspect to the relationship people have with the natural world when they feel part of something greater than themselves.

For instance, agricultural communities, populations who live in close contact with nature and, in a sense, integrate their bodies with it—are synchronized with many rhythms, right? The seasons, the plants, the animals—this truly provides the foundation for a particular type of magic that differs from specific rituals.

I’m not against rituals, but I contend that the magic represents something deeper than the rituals, right? Magic embodies a specific type of relationality to a wide range of forces surrounding us. I mean, it’s profoundly creative; it’s part of creativity. Every time your consciousness expands, you begin to see—a new perspective emerges, and it’s magical, right?

The Dangers of Commodification

So, yes, I think that capitalism feels magical and sells you, you know, a commodified form of knowledge. Nowadays, half of the movies produced for popular consumption are built on this violent magic—human beings transformed continuously—facing weapons capable of dissolving everything around them.

I’ve observed this; I hear about people watching violent content—people being blown up—it’s so intense. You ponder why people want to engage with this? Why do they crave to witness others wielding weapons that can obliterate entire worlds? You know, this profound, profound alienation. So they are, you know, banking on that reality, right? And concluding with this wheel—you know, very, very meta. So we have to be extremely cautious about that. I think we need to be consistent in our approach. Yeah, like outside—this idea isn’t working. I haven’t seen it; I haven’t witnessed it.

Evaluating the Impacts of Scientific Advancement

I think—I think there aren’t any more questions. I don’t know, do we have time for two more questions? Perhaps? Are you sure? Thank you. [Applause] You okay? Super! Um, I wondered about your thoughts on—and you’ve spoken about the criminalization of pregnancy. Yes, and then also just now about new technologies. Yes, and um, I was thinking about—I’ve been doing research myself into technologies. Yes, and we have this sort of double-edged sword: the new technologies allow us to see inside the body and monitor the body, improving fetal health. However, scientific research is also uncovering adult health issues—mental health issues—that could potentially be linked to the nine months before you’re born.

The Implications of Monitoring Technologies

So, um, the research aims to help those issues, but it also impacts women’s responsibilities regarding their behaviour. And then also, because you’re discussing institutions, the cost linked to these technologies leads researchers to conduct studies that aren’t necessarily meant for the benefit of the mother. So, what happens to that information becomes a question.

The Criminalization of Motherhood

Okay, so yes, this is an essential topic I want to discuss. What I mean by the criminalization of motherhood is—and I don’t know if this is the case here, but as I said, the United States often serves as a precursor, so keep an eye there—there are now 30 states granting rights to fetuses once they are alive. What has occurred is an inverse proportional relationship between the rights of the fetus and the rights of women.

They learned from the Irish Constitution that the rights of the fetus equate to the rights of the mother. It used to be that the mother had their own rights; what it turns out is that the more we value the fetus, the less we value the mother. The mother increasingly becomes merely a vehicle, not just in terms of her behaviour impacting fetal health.

The Increasing Scrutiny of Pregnant Women

Now women have been arrested for various reasons that never would have occurred before. Women have been arrested after car accidents when they informed police that they were pregnant. They were charged for endangering the life of the fetus. They have even been arrested for using prescribed medications because those medications could put the life of the fetus at risk—by state standards.

So it’s becoming more challenging to go to the hospital following a natural miscarriage because doctors may accuse you—they say, “Oh, this doesn’t appear natural,” inferring that you provoked it. Effectively, this makes you a suspect. Incidentally, the Pope in Argentina stated that women who have abortions are killers. You know, “Sicario” is a term for assassin; he used that term against them. So the question arises: who does he think that women are killing on behalf of? He didn’t label them as murderers, rather, he stated they were “Sicario,” suggesting they murder in service of someone or something.

The Dehumanization of Women

I don’t know if it pertains to the devil or something similar. In the United States now, it can be said that, as a woman, lawyer, and national health advocate pointed out, if you’re poor and pregnant, you have now effectively stepped outside the boundaries of the constitution. Many crimes can now be attributed to you that no other person in the country can be accused of. This is what I mean by criminalization; it serves to dehumanize women without being labelled as criminalization because it becomes—and this reflects what is happening now while connecting the present to the past through my writings on “Caliban” and…

The Surveillance of Mothers

What I’ve discovered is that they are creating surveillance systems in multiple locations where doctors must report to the police if a woman is pregnant and if they observe anything amiss, like that she’s engaging in activities deemed harmful to the fetus—then the doctor is obligated to inform the police or risk losing their medical license.

The same holds true for nurses facing sessions with the police because, in various cases, the police instruct doctors on how to conduct blood tests that could later be utilized in cold cases. There are numerous methods of blood testing, and some techniques lend themselves better for use in a cold situation than others. Thus, this creates a very dangerous and systematic situation surrounding those technologies.

Conclusion and Reflections

I think you’re right; you know, those technologies—God knows what the relationships are—and it goes beyond health considerations, right? Because once you know, it introduces—I mean, it’s deeply complicated what the application of these technologies does. But it also creates, right? It may save some lives, but on another level, it also presents an entirely new array of complications regarding what one ought to do. We know that, in India, technology has significantly contributed to the abortion of female fetuses, right? That has become clear. Yeah, so it’s very complex; it’s a crucial question.

Quiz: How well were you paying attention ?

- What open copyright book did Sylvia Federici publish?

- What does the speaker express gratitude for at the beginning of the text?

- What key element does the speaker mention as a source of strength during troubling times?

- How does the speaker characterize the current state of capitalist society?

- What social weapon does the speaker identify as essential to the current authorities?

- Which country’s president is mentioned as having publicly stated he has killed people?

- What event does the speaker note about the newly elected Brazilian president, Bolsonaro?

- According to the speaker, what does the European Union and the United Nations lack in today’s world?

- What trend does the speaker identify regarding policies in the past decades?

- What does the Mediterranean symbolize in the context of the text?

- Why does the speaker find feminism crucial in today’s world?

- How does the speaker define feminism, as opposed to institutional state feminism?

- In what historical context did the speaker refer to feminism as a movement to change society?

- What does the speaker believe feminism fundamentally addresses?

- According to the speaker, what has capitalism done to society’s most essential activities?

- What does the speaker claim is necessary for the survival of struggles?

- What does the speaker mean by “collective memory” in relation to community empowerment?

- How does the speaker connect women’s struggles with environmental issues today?

- What historical injustices does the speaker refer to when discussing women and the witch hunts?

- What does the speaker believe is necessary for “appropriate justice and acknowledgment” regarding historical witch hunts?

- How does the speaker relate the commercialization of knowledge to current educational struggles?

- How does the speaker view the relationship between debt and isolation in the context of student experiences?

- What does the speaker argue about the link between technology and capitalism?

- What does the speaker mean by the term “criminalization of pregnancy”?

- According to the speaker, why is awareness of past injustices significant for present and future societal struggles?

Answers Key:

- Caliban and the Witch

- The shelter for hosting the event and the organizers.

- The gathering of many people coming together.

- The system is shedding its masks and revealing its true nature.

- Violence.

- The Philippines.

- He supports the previous dictatorship, claiming they did not kill enough people.

- They lack a vocal presence on human rights issues.

- Policies that dispossess the majority of the world’s population.

- It represents a graveyard for those fleeing violence.

- It is vital in the current context of violence and systemic oppression.

- It should center on equality and societal change rather than merely improving women’s conditions.

- In the early 70s.

- The experiences and struggles related to reproduction in society.

- It has devalued essential life-sustaining activities.

- Creating a reproductive basis for future struggles.

- Understanding and connecting with the past empowers the present.

- Women are often at the forefront of environmental preservation and care struggles.

- The history of witch hunts illustrates systemic oppression against women.

- By teaching and sharing stories that reflect the truth of their experiences.

- It indicates a trend of viewing education as a commodity rather than a right.

- It leads to feelings of guilt and isolation that compound the exploitation.

- Technology often serves to expand capitalist exploitation and commodification.

- The increasing legal implications placed on pregnant women regarding their behavior.

- To ensure that history does not repeat itself and to foster a collective awareness of struggle.

Synopsis of themes in Witches, Witch-Hunting, and Women

Federici states the decision to publish the essays in this volume has emerged from the confluence of compelling factors. These essays mark merely the initial phase of a broader investigation—and, particularly in Part 1, revisit theories and evidence previously articulated in Caliban and the Witch—they serve as a springboard for deeper exploration.