Prof Fergus McNeill: Annotated Study of Crime and Punishment

This was developed as a ‘learning artifact’ as a part of a documentary method of using multimedia as curriculum. Following the auditor experiment with Drew Whitworth I started to use the audio recording as a tool for capturing a lesson and developing a researched learning resource for the world wide web. This has been made particularly easy by people like Fergus and Drew who are interested in sharing their knowledge.

This is an annotated study of a presentation given by Prof Fergus McNeill which involved conversation on aspects of crime, punishment and faith in change. It brings in some of the sources which McNeill draws on and aims to chunk information into themes with the aim of offering prompts to facilitate discussions in groups as well as self study; hence the embedded videos.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Fergus McNeill is a professor at the University of Glasgow, where he teaches criminology and social work. He is involved with the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research and the sociology department. Before becoming a professor in 1998, he worked for ten years in residential drug rehabilitation and as a social worker in the criminal justice system. He has done a lot of research and written extensively about punishment, rehabilitation, and alternative approaches.

Most recently, from 2017 to 2021, he led a significant project called ‘Distant Voices: Coming Home,’ funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. This project focused on helping people reintegrate into society after serving their time, using creative methods. His latest books are ‘Reimagining Rehabilitation: Beyond the Individual’ (co-authored with Lol Burke and Steve Collett) and ‘Pervasive Punishment: Making Sense of Mass Supervision’, which won the European Society of Criminology’s Book Prize in 2021.

Links to websites:

Opening

What I proposed to do: I’ve got slides here which only I can see, which is fine, because they’re really just to give me a bit of a structure of what I wanted to talk about. I’m very happy not to be interrupted, especially with such small numbers, and to make it as dialogical as we can—either as we go or you can let me ramble on for a while, and then we can stop and talk.

Personal Faith and Academic Background

On the specific question of spirituality and faith, I thought about this in advance. So, I would call myself a person of faith. My own background in that regard is in the Christian church. Interestingly, although I’m an academic and I’ve studied philosophy, history, social work, sociology, and criminology, I’ve never studied theology.

So, my appreciation of theological and spiritual questions is lay, and for that reason, I thought I wouldn’t try to insert my kind of lay understanding into the sort of academic content of the talk, but rather, I’ll keep it at a philosophical level where the connections to spiritual and theological questions will probably be quite easy to make. But I’m going to somewhat rely on you to help me make some of those connections as we go through.

Secularization and Justice

I think that’s easy to do because I think that for all that we have secularized the way that we think about crime and punishment, in fact, even today—when we’ve changed the language and been influenced by the development of law and social science and whole post-Enlightenment traditions of secularization—the fact is that spiritual questions and questions of belief, both in the sense of what I would think of as deep structures of meaning and fundamental questions about humanity and society, are unavoidably contained in everyday practical dilemmas that arise in the justice system.

Existential Questions in Crime and Punishment

So there’s literally no escaping the sort of existential and spiritual questions that lie behind crime and punishment, and so I’m very confident that we’re going to make those connections. But I’m not going to make them on my own as I go through this.

Philosophical Foundations of Justice

So I’m going to start from a paper that I wrote for a book a year or two ago, which was given the title “What Good is Punishment?” It was linked to a conference that took place a few years ago in England, organized by the Howard League for Penal Reform, which was trying to get to an even more fundamental question: What is justice in the context of criminal justice?

The Concept of Good in Criminal Justice

I reframed the question slightly, and my reframed version of it was, “What sort of good is criminal justice?” So here’s where I began. And this is, as is commonly the case with me, with philosophy—in this case, the philosophy of John Rawls, who wrote a very famous book in the 1970s called “A Theory of Justice.”

One of my favorite quotes from him is: “Justice is the first virtue of social institutions as truth is of systems of thought.” So when it comes to thinking about the constitution of human society itself, the way that we order our affairs, and the way that we establish social institutions, justice is absolutely fundamental and indeed constitutive of a good society. There is no way of conceiving of a good society without justice being at its core.

Distributive Justice and Criminal Justice

Rawls was speaking principally about distributive justice and social justice rather than criminal justice, but I think the principle applies in both contexts. The other way to think about justice, and criminal justice specifically, is to think about it as a productive good—not as something which is good in itself or which is indicative of a good society, but rather as something that we must do in order to produce other benefits.

Justice and Social Peace

That sense of justice as a productive good is wrapped up in a very common phrase, at least common to my ears, which is: “Without justice, there is no peace.” That phrase recurs in relation to all sorts of social movements and campaigns for global justice, in fact.

The Importance of Fair Resolution

But I think there’s a really profound truth in it: unless we arrive at a shared understanding that the resolution of our grievances, whatever they are, is fair and appropriate, then we don’t really settle conflicts that might arise between us—they remain unresolved, and that is disruptive of the social peace or the interpersonal peace between us. So if we can’t find a resolution that to all parties feels just, then we’re in difficulty.

Reciprocal Social Relations

I think that sense of needing peace between people, peace between communities, and peace between nations gets to a very fundamental aspect of how human beings evolved, in fact, and of how we come to live together. The central idea here, which is endorsed, I understand now, by evolutionary scientists—though that is not my field—is that reciprocal social relations, exchanges between people that enshrine certain reciprocities of respect one for another, are fundamental to the cooperation on which human life depends.

It’s as serious as that: if we can’t cooperate, if we can’t accept each other’s value and worth and dignity, then we can’t begin to do things like trade or basically live together. Without a set of reliable reciprocities in the ways that we relate to one another, we can only ever be on edge around one another, literally armed and ready to defend interests that we can’t rely on one another to respect.

The Problem of Offending

So to get past that, we need to establish a set of reciprocal social relations that allow us to live at peace. Offending and crime—that’s why it’s a problem fundamentally for me. It’s interesting that the word offense in the criminal justice system isn’t generally thought of in this way, but actually, the reason why offending is offensive is precisely because it represents a violation of reciprocal social relations. It means I can’t trust you because you haven’t abided by the implicit promise between us to respect one another.

Sanctioning and Censuring

And so we can immediately and sometimes too hastily make a swift move at this point to the idea that if a violation of those reciprocities has occurred, then we must sanction it. We must censure it and sanction it. We can’t allow that violation to stand because if we do, those reciprocal relations will atrophy and we’ll find ourselves back in a nightmare kind of, you know, Thomas Hobbes’ state of nature: red in tooth and claw, competing viciously for scarce resources—that sort of scenario. So we need to respond to wrongdoing because we have to try to find a way to sustain these reciprocities that constitute a just order of things.

Values Communication Through Sanction

A related point is that when we sanction and censure, one of the most fundamental things that we’re doing is communicating about our values. We are affirming and expressing certain values, certain reciprocities, and we’re saying something about ourselves in the process. We often talk about criminal justice as if it’s an instrumental logic, like deterrence would be a classic example of an instrumental logic. But in fact, for me, it’s much more fundamental than that. There’s something vital about the pursuit of justice; it’s so central to the project of human social life and to our sense of being recognized by one another that we can’t reduce it to questions of cost-benefit calculations.

The Complexity of Sanctioning

To give you an obvious example: if I commit an offense and if a wise criminologist comes to you and says, “I can absolutely guarantee you on the basis of irrefutable scientific evidence from randomized control trials that giving Fergus a month in the Ritz at the state’s expense and some time to work will guarantee that he won’t reoffend,” you might still reasonably say, “In what sense is that justice?” But if you were a pure utilitarian, you would have no reason to complain about that resolution because it would be crime-reducing and in everyone’s collective interest and incredibly cheap by comparison with what we actually do when we imprison.

Normative Principles in Criminal Justice

So it’s not just about those calculative arguments; it’s about something more fundamentally communicative. Another layer of complexity is that when we sanction, we exercise power, and because it’s the state and the state’s organs that sanction, it can do it in ways that are fundamentally negative or more positive, and I’ll explain a bit more about these two forms in a moment. What actually happens when we make those choices about the imposition of sanctions is an object of empirical inquiry. So criminologists, sociologists, and others can and do study that, and what we find out then has normative consequences because if what we think we’re doing produces outcomes that are at odds with those we pursue, we should care about that.

Yes, what does “normative” mean? Oh, sorry. “Normative” means relating to norms, or based on principles rather than evidence. There’s always a relationship between the normative, the principle, and the evidence. So if my principle is, “I could have a principle that we ought to deter crime,” but if I then produce compelling empirical evidence that what we’re doing is not deterring crime, then you have a problem with the application of that normative principle. So we need to keep the evidence and the principle in dialogue with one another to make sure that we’re not doing things that are counterproductive.

The Definition of Punishment

One of my favorite scholars of punishment is David Garland, who’s a Dundonian who used to work at Edinburgh University and now at New York University. Recently, he’s kind of reexamined the work of the French sociologist Emile Durkheim, and he sums up Durkheim’s position on punishment in this way: the essence of punishment, Durkheim claims, is irrational, unthinking emotion driven by outrage at the violation of sacred values or else by sympathy for fellow individuals and their sufferings.

Expressive Elements of Punishment

So fundamentally, according to Durkheim, what’s going on in punishment is expressive, value-driven, and the values are either sacred—a front at the violation of God’s law—or under a more modern secular world, what replaces sacred values is respect for individual rights. So that becomes something that we hold sacred; we tend to do in the way that we talk about human rights.

If a victim’s rights are violated by an offender, then that evokes, and it should evoke, a profound and visceral reaction. Durkheim is not criticizing us here; he’s saying that’s right, that’s normal, and that’s a sign that we have shared values that we hold sacred. We need those to have social solidarity. The question is: what do we do with them? How do we give vent to them and exercise them?

Beccaria’s Enlightenment Perspective

Contrast that with another, even earlier thinker, Cesare Beccaria, who was a fundamental figure in the Enlightenment as it relates to questions of crime and punishment. He says this in very flowery language, translated, I think, from the Italian: “Would you prevent crimes? Let liberty be attended with knowledge. As knowledge extends, the disadvantages which attended diminish and the advantages increase. Knowledge facilitates the comparison of objects by showing them in different points of view. When the clouds of ignorance are dispelled by the radiance of knowledge, authority trembles, but the force of the law remains immovable.”

The Need for Balancing Principles

So we need principles; we need evidence; we need science; we need law; we need the empirical; we need the normative. Okay, so that was a bit of background. Now I’m going to kind of drill down specifically into the question of punishment.

Liberal Definition of Punishment

A standard definition of punishment in liberal philosophy, which is the kind of guiding philosophy for the liberal democracies that we live in in the West, goes something like this: there are three parts:

1. Punishment is an intentional infliction of harm or hardship on a person. That’s point one, so there’s some kind of hard treatment.

2. That’s imposed in order to reproach or censure that person for a criminal wrong that the person is found to have committed. So it has to have that censure. It has to be for a criminal wrong, and it has to be properly found through a due process that the wrong was committed by that person.

3. It has to be inflicted by someone entitled to make that wrong his or her business and to perform the punishing act. So a legitimate authority has to be the punisher.

The Unusual Nature of Punishment

That definition comes from a Cambridge scholar called Antje du Bois-Pedain, whose work I’ve been reading recently. Now it’s worth just pausing for a minute and thinking about how odd this is. These three conditions are unusual in the societies that we live in because they’re liberal democracies. So liberals, with a small “l,” prize individual liberty, autonomy, freedom of movement, self-interest, and the right to pursue your self-interest, the right to hold your property.

Those are the prized things that the liberal subject is said to possess, and yet now we’re saying the state can trample all over that under these conditions. So it’s important to remember that we can’t usually inflict these harms on one another—that’s against the rules—but we can do it in this case because we’re referring back to a wrong that’s been done that must be communicated about and because the authority is lawful and legitimated. That’s the argument.

Bois-pedain, A.D. (2017). Punishment as an Inclusionary Practice: Sentencing in a Liberal Constitutional State.

The Fourth Dimension of Punishment

But the most interesting thing about du Bois-Pedain’s recent recounting of this story is that she adds a fourth dimension which is usually missed, and this is what I really want to talk about. And actually, I think this is where many of the connections that we might make to theology and spirituality really begin to come into play. There are lots of religious texts, I guess, that deal with condemnation and justice in the sense of the need to find a remedy for a wrong. There’s also, though, a lot of religious texts and experiences that relate to this fourth element.

Future Coexistence Post-Punishment

Here she says, “As a general social practice, punishment does not merely mark out the punished person’s actions as wrong and blame him for engaging in the wrongful act; it also defines how the punished person and the punisher will move forward from here.” The penal agent, the one exercising the authority to punish, lays down the terms of their future coexistence with the offender in a shared social world. Because this is punishment’s central social function, there is a reintegrative momentum inherent in punishment that gives the offender himself an interest in being punished. Far from threatening or challenging an offender’s membership in the community, punishment exists to reassert and reinforce it.

The Role of Atonement and Restitution

So again, this is classic liberal philosophy, but the point is that the way back from the wrong is to pay the debt, and with the debt settled, we are renegotiating living together. The reciprocities are restored because the harm is taken seriously, apologies offered, and remedy is provided. So this question of reintegrative momentum is absolutely at the heart of what I want to talk about.

Proportionality and Punishment

Sorry, do any of those four points incorporate proportionality, as in the punishment shouldn’t be too harsh? Seriousness? Yeah, indeed. And of course, if the punishment is excessive, then it violates the—so I’ll go back, and most liberals would say the first thing about punishment, because it’s such an unusual violation of the normally respected rights of the citizen, is that we must do it as little as possible. So that’s parsimony; that’s formally called parsimony.

The second principle is proportionality, and it’s linked. So that is that the punishment should fit the crime. We tend to hear that statement, which is a biblically derived statement from “Lex Talionis”—“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” We tend to hear that now as a statement in favor of severity, but actually, it’s a limiting principle. What it’s saying is no more than the harm done is justified. We can aim to balance, but we certainly can’t be illegitimately excessive in the way that we pursue retribution. So yes, proportionality is critically important.

Challenges of Reintegration

Now so far I’ve been kind of assuming a liberal philosophy—which, of course, I’m not even sure that I share it—so I’ll just put out there, but even if you don’t agree with du Bois-Pedain’s argument, it doesn’t really matter. If you’re a reductivist—if you want to reduce crime—you have to care about reintegration because without it, there’s an enormous amount of criminological evidence that if the person isn’t integrated successfully, the likelihood of recidivism is increased.

So there’s no escaping it from a reductivist point of view, and if you’re a retributivist, it follows from the proportionality principle and from the parsimony principle that you have to make the punishment end. If the debt is ten years, then ten years and one day is too much punishment. Ending punishment requires integration; if the person isn’t restored to the discipline of the debt, then the whole kind of metric that we’re trying to establish in this approach fails.

Adjacent Issues of Social Justice

[commentator] I’m distracted by something that’s been with me for a long time, and maybe I should just voice it because it’s distracting me, and that is legitimate anger disenfranchised people. So if you have people who, like Franz Fanon, have a right to be angry when things have been unfair to a group of people—like the indigenous communities in Canada—and okay, they’re offending and there are all sorts of programs to address that, but they have had an unjust situation. And you might argue that blacks in America may offend… but so could you put this into context. Yeah, I would say that’s not what you’re talking about, but I’m finding that I’m just thinking about it.

Structural Injustices and Criminalization

[McNeill] No, no, you’re quite right, and I couldn’t agree more. I’ll say something about it now, and then I’ll come back; it fits into another part. I know it’s not what you’re saying, but the big problem with the liberal model is that it assumes that what we’re trying to do in punishment is restore a just social order, and if we don’t have a just social order in the first place, then the application of these principles goes awry. And that’s a pretty fundamental problem.

Judith Butler’s Critique of Liberalism

There’s a second problem, incidentally, which is equally troubling—one that I’ve only thought about more recently from listening to Judith Butler give the Gifford Lectures at the University of Glasgow this year. She’s a gender studies scholar who is profoundly influential globally. The specific point that she made in the lectures—and this is getting quite philosophical, so let me know if this doesn’t make sense to you—but basically, I mentioned Thomas Hobbes earlier and this idea of the liberal subject as a sort of rights-bearing, self-interested, autonomous individual.

She mocks that idea, Judith Butler in her lectures, and says, “Why haven’t we noticed that that subject is gendered and has a certain ethnicity—that is, a white, middle-class, property-owning subject and the kind of founding myth of liberalism is based around a certain conceptualization of the interests of a certain subsection of the population, and it’s not an accident that it’s those people that the system best defends.”

Judith Butler – Gifford Lecture

Intersectional Perspectives

That’s part of the problem for the Black Lives Matter movement. But I might want to rely on the state’s exercise of its authority to sustain and protect my interests, but that’s because I can. Whereas if I’m a young African-American man in a ghetto in name your American state, then I don’t have that protection, and the state isn’t functioning in that way.

She makes a second point, though, which is equally important, which is to say that the idea of autonomy of the liberal subject—the independence as something that we have and that we should strive to protect—is also a fiction. We’re all born; because we are all born, in fact, we are gestated in dependency, and we are delivered into interdependency, and we never move beyond that.

A Relational Ethic of Care

So she would therefore argue that what we need to pursue is a relational ethic of care, not the pursuit of individual interests of subjects protected equally under the law, which is the fiction. So I’m not advancing this argument as somebody who is committed to liberalism philosophically. I’m trying to outline these principles that govern our system as it stands so I’m kind of describing them in their own terms in order to tease apart some of their tensions and as I go on, you’ll see how these tensions recur and also maybe how we might have to work to address them.

Reintegration as a Common Pursuit

Okay, so so far we’ve got to the point, I think, where I’ve argued that whether you’re a reductivist or a retributivist, whether you buy this liberal argument or not, you have to care about reintegrative momentum. You have to care about whether punishment brings people back in a better condition to live peacefully in the community, to live at peace in the community.

The Challenges of Successful Reintegration

Of course, if you’re a criminologist or a sociologist who studies the penal system, you know that, in fact, reintegrative momentum is very hard to generate and very easy to lose. I could quote lots of studies that describe how that is lost at the point of sentencing, lost in the way that we implement sentences, and lost in the way that we handle the ending of sentences—none of which I think we’re particularly good at from the perspective of thinking about reintegration.

The Justification for Criminalization

There’s a prior problem which relates to why and when we choose to criminalize and penalize at all. So if when we seek to right wrongs—our primary purpose is to secure relational reintegration, how should that influence the choices that we make about the way that we respond to wrongs? So I ask my students this question today: When somebody that you love wrongs you, what do you want to happen to them or for them? And what do you want from them?

Let’s just ask that, not as a rhetorical question. Think about this in the context of people that you care most about in the world and that care most about you, but nonetheless, in some significant way, they wrong you. What do you want the resolution of that wrong to look like or to involve? What do you will for that person ?

Seeking Acknowledgment and Remorse

[Commentator] I would say that I would like, first and foremost, an acknowledgment by the person of whatever act it was, an expression of regret about it, and a commitment to not do it again. And then let it go. [McNeill] Okay, however serious the wrong, that would probably be the way I would deal with lots of minor wrongs.

Acknowledging Serious Wrongs

[Commentator] Well, I suppose, if they tried to murder me, say in some serious case, I guess I would think that that would be not totally for me to deal with.

Indicators of Sincere Apology

[McNeill] What would actually—going back to less serious wrongs—what would persuade you that the apology was real and sincere? I mean, persuade you to the extent that you were really able and willing to set aside the wrong ?

Expectations of Empathy

[Commentator] Well, the obvious aspect would be that I would hope that it was sincere. Only time would reveal if it had been sincere, but I think that I would probably give the benefit of the doubt if I had any.

The Role of Understanding in Apologies

[McNeill] Any other thoughts or any other reactions? [Commentator] I would expect that person to show some kind of empathy, some kind of understanding of the effect—whether it was just an emotional effect, say that it had on me, the thing that they did—and that would be part of understanding whether or not they were sincere. If I had some thought that they understood what they had done to me, I also wanted to bring in, I suppose, a Christian idea of forgiveness as well into it. You used words like “set aside.” I don’t know if you meant forgiveness there or not.

The Complexity of Forgiveness

[McNeill] Well, I don’t know either. Maybe I do, and maybe forgiveness is not the setting aside so much as the working through. We often—in criminology—there’s an interesting literature on the question of what we do with convictions—criminal convictions—and there are arguments there about what should be formally forgotten or forgiven and what it is to seal the record and therefore treat the past as completely resolved. To the extent that we no longer consider it to have happened almost, we kind of try to rewrite history.

The Nature of True Forgiveness

I’m not sure whether forgiveness aims to go that far. I think for me, forgiveness remembers but doesn’t hold against.

The Dynamics Between Remembering and Forgetting

Perhaps people have other conceptions of forgiveness. If you’d had forgotten it, I mean forgetting can surely be something that can’t be chosen; either you remember, or you forget. I think it’s the holding against that you can perhaps do something about willfully. But that’s just my—this is me traveling into lay areas where I don’t claim to have any particular expertise.

Repairing Reciprocal Relations

So I had written here to repair reciprocal relations. If we think about it in the context of those sorts of close relationships, we usually need apology, remorse, and repair. We didn’t mention that, but actually one of the things that would convince me that an apology is sincere is if somebody actually tries to make good on the wrong if it’s a recoverable wrong.

So, you know, if they break my favorite guitar, which would be a gross offense in my house, they might offer to buy me a new one; that could be a reasonable response as opposed to just saying, “I’m sorry about your guitar,” but “hey, you’ve got another one, don’t worry about it.” I wouldn’t regard that as sincere because it doesn’t take seriously my loss. It’s not just the financial loss of the instrument, but what the guitar meant to me.

The Context of Intentionality in Wrongdoing

You see a big difference if the guitar was mistreated in a culpable way versus whether it was an accident. It would make a difference. So, the criminal law takes account of that in thinking about intentionality and blameworthiness and culpability—or tries to, you know, admittedly, in a clumsy way. What I think is interesting—and this is the second question that I asked my students—is if you respond that way to people who love you, why do you think we tend to respond differently to people who are strangers?

The Influence of Relationship on Responses to Wrongdoing

In one sense, you could argue that if people who love us wrong us, we’re entitled—we should. Well, maybe that’s too pejorative a comment. But we might be entitled to be more angry. So what is it that entitles us to? Why do we reserve our punitiveness for strangers and a willingness to pursue this more sort of reparative route with intimates, for want of a better expression?

I think the sociological or anthropological answer is I’m invested in one relationship, and I want it to endure. The other one? Not so much. And also perhaps my emotions in relation to the wrong are conditioned in all sorts of more or less subtle ways through culture and structure. Maybe we’ll come back to that later.

Non-Conversational Resolutions to Wrongdoing

So, mostly my point is that when wrongs occur between people, we mostly pursue the resolution through conversation and cooperation. That’s actually the way we handle most wrongs. But in relation to serious wrongs—serious criminal wrongs—what we have is a system of compulsion and constraint, and there’s a problem with compulsion and constraint if the remedy is a restored relationship.

Legitimacy of State Power

If the route to the remedy is through compulsion and constraint, then what we’re seeing is that force—and, in fact, I would go further and say violence—is now in play in the criminal justice system. We would think of that conventionally as legitimated violence. The state is, I mean this in a kind of almost literal sense: the state’s agent is entitled to lift the offender bodily and put them in the back of a van and take them to a place and lock them away. That’s violence.

The Challenge of Dignity in Punishment

It’s not violence in the sense of beating anybody up, but it’s a violent interference with the liberty and autonomy of the subjects. Even lesser sanctions, or sanctions that we would generally judge to be lesser, like supervision, probation, or parole—that’s suspended violence because what lies behind it is that threat that if you don’t comply with what is being compulsorily required of you, then the state is entitled to act on your body in that way, and will do so, which is no basis for a conversation—if you see what I mean.

The Disconnect Between Punishment and Conversation

You don’t usually feel well-disposed to get into conversations with people who are exercising coercive control over you because that feels like an abuse of your personhood—a refusal to engage with you as a dignified subject. So, that’s a problem for reintegrative momentum. If we’re trying to restore relationships, and we’re having to do it—and I’m not arguing against this here—if we’re doing it through compulsion and constraint, then the path that we’re taking is a difficult one. That’s all I’m saying.

Interpersonal Understanding and Social Responsibility

[Commentator] Can I just make a few points. In the one-to-one relational situation—the person whose action is deemed unacceptable, I think it would be quite important to check into what that person is putting on the table. We can’t just look at the lines of our own perception. So someone might react in a way that you find unacceptable, but you might find that as perfectly acceptable. I think the same applies at a social level.

The whole business of reintegration—I mean, someone might, for example, view their actions in relation to a normalized violence in society, and the society itself has certain responsibilities. So to place the responsibility on individuals and to integrate them back into a society that normalizes the violent then—I think it’s again important to check in they may be acting up because they might fundamentally disagree with certain aspects of society.

The Role of Fair Arbitration in Justice

Yeah, I agree. You could argue that’s one reason why we need some sort of process of fair arbitration, which is in fact what a court system is intended to provide. Because we can take legitimate, legitimately different perspectives on questions of values and conduct within the constraints of a system of law which might bind us both. Certainly, the meaning of acts, the significance of acts, the extent of harms—all of those things are things in which we might reasonably disagree about.

The Importance of Dialogue in Reintegration

At the level of interpersonal mediation, to draw on your experience, it’s critically important to take the time to explore the meaning of what happened for the different parties involved and to explore the possibility of arriving at some, if not a shared understanding, then a shared understanding of the two different understandings, if you follow my logic. That is enough to help us move beyond what happened.

The Consequences of Coercive Approaches

My problem is that when we go to that system of constraint and compulsion, what we’re doing is silencing one of the parties in the conflict and saying, “You’re no longer a participant in a dialogue about this wrong. You’re being told—you’re being told to use a Scottish expression—what this means, what it was and what has to happen next.”

The Choice Between Negative and Positive Power

So let me just kind of roll on because a lot of what you’re raising in your questions is going to come together quite nicely, I think, as we get to the end in not too long. So we’re at the point in the kind of logic here where compulsion and constraint create problems, but sometimes we may feel that we have to use those to respond to serious wrongs, particularly if we have an intransigent person who’s done the wrong and isn’t prepared to apologize or even engage.

The Nature of Negative Power

So then we confront a choice about whether we use that negative power or positive power, that I mentioned earlier. So the negative power, I can discuss metaphorically as a slicing off—and this is often the way that we think of retribution. So in order to restore the balance, you’ve seized an unfair advantage that breaches the social contract, so now we’re going to have to slice something off from you, and that remedies the imbalance.

Forms of Injury Associated with Punishment

We’re going to impose harm. At the extreme, in some societies that would mean taking away life; in our Scottish context, it would mean taking away liberty. At somewhat intermediate levels, it might mean taking away time or demanding effort—think about community service or payback. It might mean taking away money in the form of a fine or compensation. It might mean taking away some element of a person’s worth, civic standing, or status—that’s what conviction does.

Negative Sanctions and Reintegration Challenges

There are all sorts of negative exercises of sanctioning power, but the problem, of course, is that all of them do damage to the capacity of the person whose reintegration we are fundamentally invested in.

The Issue of Stigma

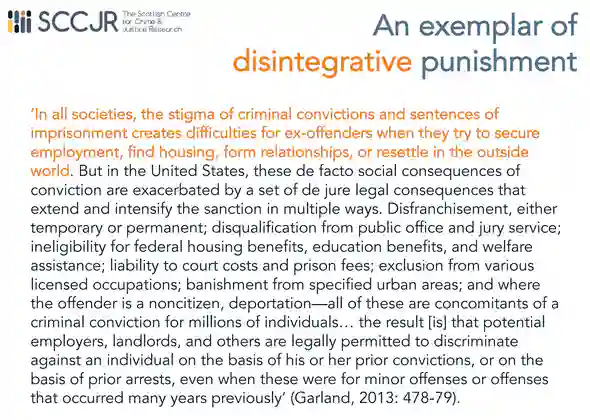

We’re now adding to compulsion and constraint incapacitation, or a disabling effect, to the harms that we’re imposing. So our exemplar of disintegrative punishment is America at the moment, most including most American colleagues would agree. I just want to read to you from David Garland here summing up this problem. He says: “In all societies, the stigma of criminal convictions and sentences of imprisonment creates difficulties for ex-offenders when they try to secure employment, find housing, form relationships, or resettle in the outside world.

But in the United States, these de facto social consequences, these real factual social consequences of conviction, are exacerbated by a set of legal consequences that extend and intensify the sanction in multiple ways: disenfranchisement, either temporary or permanent; disqualification from public office or jury service; eligibility for federal housing benefits, education benefits, welfare assistance; liability to court costs and prison fees; exclusion from various licensed occupations; banishment from specific urban areas; and, where the offenders are noncitizens, deportation. All of these are concomitants of a criminal conviction for millions of individuals.” [Garland, 2013]

Garland, D. (2013). PENALITY AND THE PENAL STATE. Criminology, 51, 475-517.

The Polar Opposite of Reintegration Momentum

The result is that potential employers, landlords, and others are legally permitted to discriminate against an individual on the basis of his or her prior convictions or even on the basis of prior arrests, even when these were for minor offenses or offenses that occurred many years previously. So it’s the polar opposite of reintegrative momentum; it’s a momentum towards permanent exclusion.

The Path to Generating Reintegration

In that context, I’m not suggesting that we are doing a particularly excellent job of reintegration here. So what might we do in a sanctioning system that actually generates reintegrative momentum? What might accelerate that process?

Positive Power and Life Enhancement

Here you could think about using power in positive ways to elicit good from people. So the positive forms of reparation that might be, in fact, life-enhancing for them and for those to whom they are making repair. You could think about this in terms of the constructive use of time and work; you could think about it as finding a way to work for the enhancement of worth and the compensation of loss.

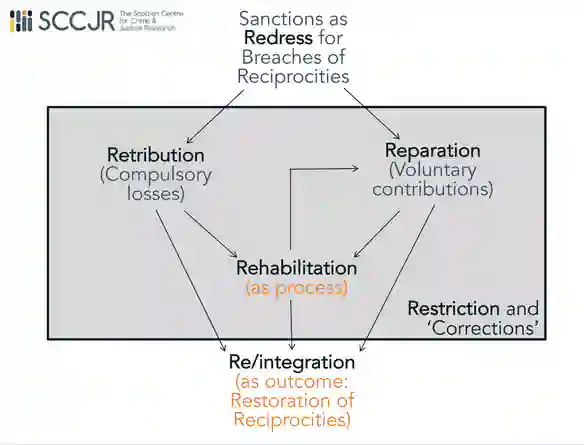

The Two Tracks Toward Reintegration

And the way that I put these sets of possibilities together in a single model is to say that, okay, we have the notion of sanctions providing redress for these breaches of reciprocal social relations. We can go down two tracks. Most of the time, certainly in our personal lives and in dealing with non-criminal wrongs, we take the reparative track.

We invite voluntary contributions, like apology, like taking seriously the wrong, paying attention thoughtfully and empathically to the suffering that you might have caused, maybe finding a way to make reparation for that or just demonstrating, in some way, the sincerity of our apology by going out of our way to be kind to that person or to show that we feel indebted to them because of the harm that we’ve caused.

Rehabilitation and the Road to Reintegration

With sufficient demonstration of that attitude and disposition, we are reintegrated through that track. And that track—rehabilitation—plays a role, but mostly its function is to enable us to make reparations. So, for example, if my interpersonal wrong is that, let’s say, in the context of employment, it comes to light that I’ve been employing an unconscious bias in hiring decisions or in promotion decisions, then the right reaction to that is, first of all, for me to acknowledge it, apologize for it, but then the other thing I do is go on some training to understand my unconscious bias better and to practice my decision-making differently in the future.

The Necessity of Rehabilitation

That’s rehabilitation. That’s me being prepared to act better in the future. The other track, the negative track, is retribution and the imposition of compulsory losses. But, as I said before, even on that track, we have to care about rehabilitation because it’s the route that gets us back to integration.

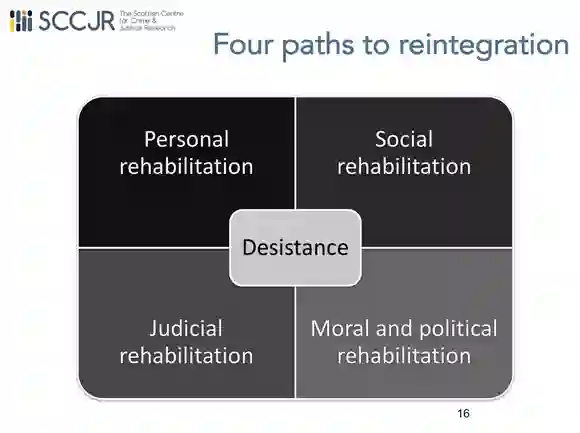

So, I’m going to finish just by talking about four interwoven paths that take us toward reintegration. This is based on a model which has evolved from empirical research looking at how people do make it back, so it’s kind of examining the road to reintegration and discerning the elements that facilitate that journey.

The Four Tracks of Rehabilitation

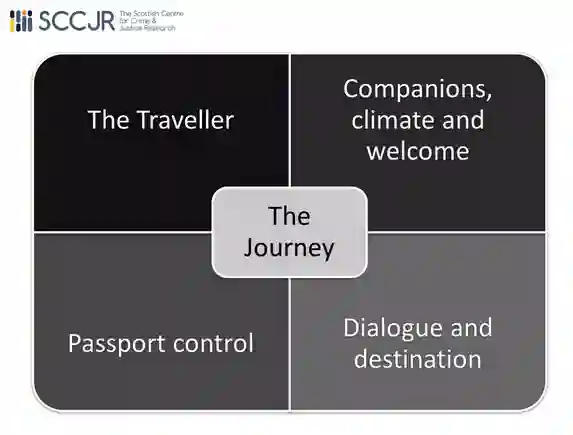

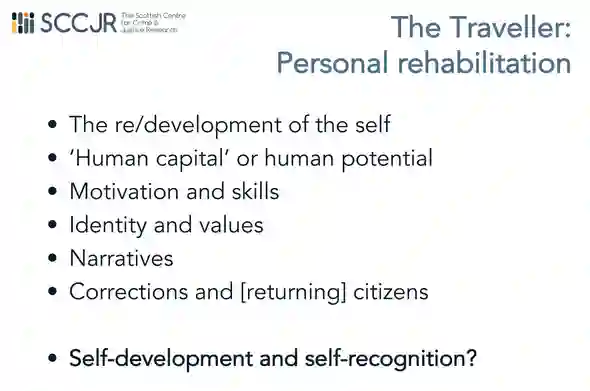

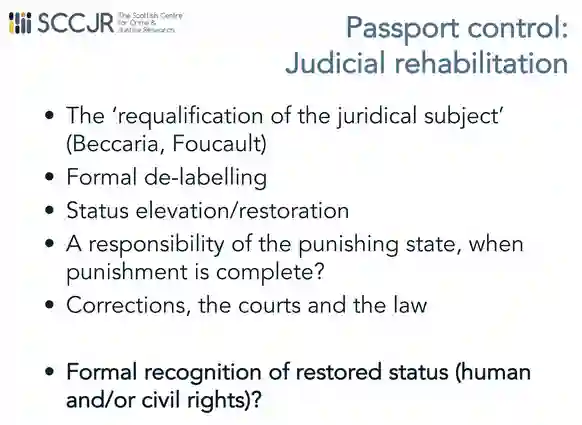

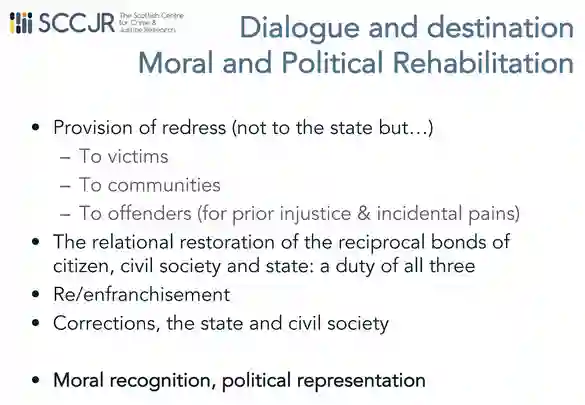

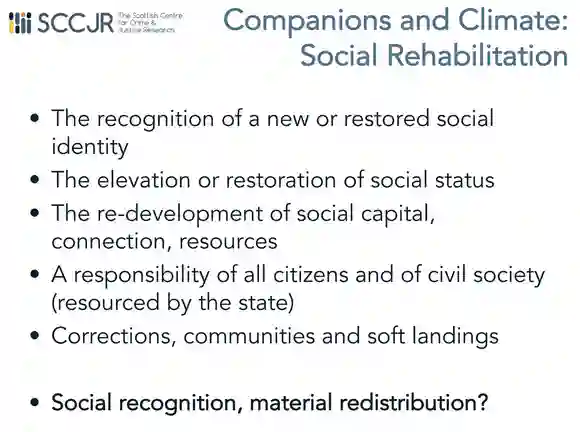

These four tracks I’ve called personal rehabilitation, social rehabilitation, judicial rehabilitation, and moral and political rehabilitation. To think about them by analogy: if we think about reintegration as a journey, personal rehabilitation is about the traveler—what is it that they need? What skill or aptitude or fitness do they have to develop to be fit for the journey?

Judicial rehabilitation is like passport control: what is the certification that guarantees them passage? Social rehabilitation is about the companions that we travel with or that we meet along the way—the climate that we travel in, the welcome that we receive. Finally, moral and political rehabilitation is about the dialogue that we engage in along the way and also about where we finally arrive.

The Importance of Personal Development

The traveler, first of all, may need some sense of redevelopment of themselves—maybe some issue of human potential. We were talking about education earlier, human capital, or a shift in motivation; the acquisition of new skills more generally. The evidence here suggests that there can also be important changes in narrative and identity—a sense of who we are, where we’re going, what we believe in.

The Passport Control of Justice

So all of these are sort of intrinsic to the individual who is returning and their kind of disposition to their own return or their fitness for their own return. I would characterize these as being linked to projects of self-development and the importance of self-recognition of one’s own identity as a returning citizen, for lack of a better expression.

Restoring Legal Rights

The passport control—judicial rehabilitation—is about the re-qualification of the judicial subject; that’s old language from Beccaria again, meaning that you are restored in your rights, that you are formally and fully dismissed. So you’re no longer a criminal or an offender—not even an ex-offender or an ex-criminal. That involves status elevation and restoration; some kind of process that brings the person fully back into equal citizenship.

Responsibilities of the Punishing State

I argue that that’s a responsibility of the punishing state: to bring punishment to an end—and that’s a function for our courts. So that’s about formal systemic recognition of restored status.

Social Rehabilitation

Social rehabilitation is about companions in climate. So this is not about whether the law states that I’m back, but rather about whether you accept me back and on what terms. Do you recognize me? Do you accept me as a neighbor or as a fellow citizen? As a member of the club or the association? That’s about social status, social connection, social capital, social resources—and actually it confers responsibilities on all of us, the receiving community, on whose behalf punishment has been exercised.

We’re not entitled to be passive in that process; we are obliged to be active recipients of people who are returning. So that’s about social recognition. Finally, the question of dialogue—and this returns us to your point about the existence of prior injustices and the significance of inequalities in this project.

The Impact of Historical Injustices

So if we think only at the level of the act for which redress has been provided, then we’re in the territory of mediation—we’re in the territory of victims, communities, and offenders getting together and figuring out what redress has been provided and how it satisfies the victim’s legitimate interests.

Shared Responsibility in Crime

But as I’m sure you’ve been aware from your practice experience, and as you raised in relation to the indigenous people or ethnic minorities who are over-policed and over-penalized—if there’s a prior injustice, then it can certainly be argued, I think, that the state is complicit and bears responsibility for this offense too.

The Complexity of Causality

If I’m a former child in care whose offending is driven by drug use—which is driven by trauma for which the state bears some responsibility—then I may be responsible for my actions and I wouldn’t necessarily argue against that. Except in extreme cases where the distress or the compulsion was so significant that there really was very little choice taking place, but I don’t need to have that level of compulsion to make an argument that there’s collective responsibility in play here.

Accountability Across Society

And the collective responsibility really is collective—if a significant part of the conditions that produced the original trauma was related to material inequalities that are the result, for example, of a lack of political will from the electorate, which did not choose to support parties that were prepared to tax at a level that would have addressed the social inequalities that created the conditions that generated the trauma that led to the addiction. So, you go back up the causal chain far enough, and you find that accountability for offending is shared.

The Direction of Redress

So I argue that the dialogue and the destination is about redress flowing in all directions, to different degrees, in different scenarios. For indigenous people, there are post-colonial debts that have to be weighed into the equation here. When we’re talking about the relational restoration of bonds between citizens, civil society, and state, there are duties across all of those.

The Importance of Enfranchisement

One sort of slight caveat or diversion here, but an important one for me, is that this is also why enfranchisement is so important in the context of punishment. If a person is formally disenfranchised, what that says is that they’re not entitled to speak politically. If a person is not entitled to speak, then they can’t be a participant in a dialogue. In that context, rehabilitative efforts can only be authoritarian and monological or pedagogical. They’re a lecture; they’re not a conversation.

A Metaphor for Repairing Social Fabric

That’s one of the reasons why I’m very supportive of enfranchisement. I’m going to finish just by leaving you with a kind of metaphor for what I’ve been trying to talk about. The metaphor is to go back to the argument about what has fundamentally caused offense: it’s that someone has acted in such a way that there is a tear in the social fabric.

The Relational Nature of Repair

We’ve been relying on the completeness of a system of mutual recognition and respect, and something has happened which has ripped that. That may be a large tear or a small tear; it doesn’t actually matter. A small one can become a large one if it’s left unattended. So there’s a tear, but you don’t fix a tear by working on one side of it. In most of the time, in our criminal justice system, that’s what we do.

The Limitations of Individual Rehabilitation

We basically say the offender has to rehabilitate themselves or be rehabilitated to be fit for reinsertion. That isn’t relational repair, and it can’t possibly fix a tear in the social fabric. So I argue that the tear and the repair are both relational—between the people involved, between civil society, citizen, and state—and that we need mutual recognition to characterize the way that we repair the tear here through social structures and cultures.

Addressing Social Inequities

Some of where we were getting to with those final thoughts shape the relational possibilities, and if we live in societies that are profoundly unjust, atomized, repressive, punitive, and stigmatizing in their response to difference, then we’re in some difficulty. However hard that is, we don’t really have any choice but to work at fixing the tear.

The Pain of Healing and the Value of Community

In relation to that task, all I would say to finish is that, again, to extend the metaphor, the needle hurts but the thread binds, and it’s better to live with a scar than an open wound.

Conclusion

So that was about an hour of me waffling around with some very useful interventions and questions, but I don’t know where you would like to take the conversation next. I didn’t, apart from near the beginning, specifically attend to the questions of faith or spirituality, but I think they’re very much implicit. I was thinking even today about the idea of reconciliation.

I was thinking about atonement; you can think about repentance in connection with the question of apology and sincerity; you can think about penitence in that context. There are lots of ideas that might have some bearing, and that’s just from my particular tradition. I don’t know from other faith traditions what sorts of ideas might resonate or indeed extend or contradict some of these ways of thinking that I’ve been drawing from philosophy mostly.

Spiritual Dimensions of Justice

One approach would be that from a more spiritual perspective, you might start from a basis of the fundamental dignity of humanity, and that might lead one to be opposed to, say, capital punishment, so one might take quite a strong view about an action. But nevertheless, one might want to protect the dignity of the person behind that action.

Normalizing Grievances

So that we—one way in which you could cut across some of these ideas and go back to the point which I think you came around to a bit—this aspect that someone might legitimately feel that there are certain things normalized in society which they feel they have to raise their conscience in relation to. For them, they’re not willing to be reintegrated back into what they see as an unjust situation.

Recognizing Agency and Reciprocity

So there’s that aspect too. I also feel this reciprocal aspect. I feel many people in society don’t feel they have much agency in a reciprocal relation. It’s more of like an imposed value framework or an imposed set of norms.

The Challenge of Imposed Values

So I think we see that almost at the level of Scotland as a country, in terms of communities too. I think certain things feel imposed rather than meaningfully relational in a mutually respectful sense. I think that’s definitely lacking in many ways. So yeah, I think that sort of complicates it. I don’t think we can assume that this reciprocity exists.

The Importance of Supportive Structures

[Commentator] I feel I’m sure many people will feel that they don’t have access to that because they haven’t been given the background and support to create those connections in an effective way. [McNeill] Yeah, I completely agree. And again, that’s the difficulty of starting with a fiction, like the liberal fiction, and then trying to think through its implications without necessarily attending to what might bring that into being or make it more real for people. What you’ve just described sounds exactly like living in a situation where we feel coerced and constrained by forces beyond our control a lot of the time—not just in relation to the exercise of penal power in response to criminalized wrongs but in a more generalized sense.

Modern Challenges and Historical Perspectives

Interestingly, your point about human dignity is one that Durkheim anticipated. He argued that this was at the turn of the 20th century, but he argued that with kind of religious values moving into history—he thought moral individualism would be the force that would drive the sense of the sacred. But what he expected was that we would apply that on both sides of the offender-victim divide.

Just in the same way that we would be rightly appalled at the suffering of the victim, we would also find it intolerable to imagine doing certain things to the offender. Certain sort of pre-modern things like corporal punishment or capital punishment would drive us towards what he called restitutive justice, which is very linked to the kind of reparative ideas that I’ve been describing—just restitution, to make restitution rather than to repress through violence.

The Regression of Restitutive Justice

This is what he felt characterized the kind of pre-Enlightenment approach to punishment—more brutal corporal and capital punishments. But he was wrong. His vision of social progress through modernity towards restitutive justice—even he noticed that before he died, he was depressed by the fact that the forms of restitutive justice that he expected weren’t emerging. What was emerging and becoming the sort of default mode of punishment was the prison, and he was troubled by that.

Current Issues of Inequity

So yes, it’s interesting. I find there’s an awful lot in his sociology of punishment which I find very compelling, but what I find so interesting is that we’ve gone backwards from the kind of position that he imagined toward more repressive and more punitive responses. Even to begin to celebrate practices that a generation ago we would have found abhorrent.

Observations on Social Justice

I think there’s so much obvious injustice, and it underpins the criminal justice system. Just the fact of who winds up in prison—it’s poor people or people of color who are predominantly in that situation. If you get someone, I used to meet people who would get charged and sent to prison because they had overclaimed deliberately or accidentally social security money. It would be a total rampage, yet people can use offshore accounts to avoid tax. You know, they spend billions on nuclear weapons, but they can’t provide decent care to people.

The Misplaced Focus on Minor Offenses

These are the kind of things I feel focusing on some of the small misdemeanors that people do seem to me to be missing the point. I think that’s a sign that from the upper echelons of society, there’s no intention to care.

The Inequities of the Legal System

Well, I think that, yes, and that’s very, again, I think that’s exactly right and also deeply troubling. On one level, I would argue that the law has always favored the property-owning classes. Any Marxist worth their salt would have made that argument for a couple of centuries now. The point now is that it’s so—50 years ago, people would have believed that the system wasn’t rigged in that sense; maybe it was rigged, but it would have had a sense of legitimacy at that point.

The Crisis of Legitimacy

Now it seems to me—and this could be a good thing or a bad thing—it seems to be more out in the open that the kind of inequalities in terms of who and what is criminalized and with what effect is so much more apparent that it undermines the legitimacy of the whole legal system.

Crisis of Legitimacy and Social Change

On one level, you could say that might be good in the sense that it might provoke a crisis of legitimacy that drives more significant social change and political change. On the other hand, it could leave us in a situation where there’s really very little respect for the law in the round, which could produce significant difficulties in relation to social disorder, and I don’t just mean for white, middle-class men. I mean for everybody; that could be—and you get cynicism, for instance.

Public Perception of Wealth and Responsibility

We’re all suffering—maybe—well, some people far more than I am—but for the bankers, you know basically there’s the MPs’ expenses scandal, there’s endless examples. The tax evasion and avoidance stuff. This was sort of driven home to me particularly forcefully when I was watching an episode of “Question Time,” and it was just after—I’ll just, since we’re being recorded, I won’t name names for fear of libel—but it was just after a famous star from a boy band, no longer a boy, had had a case against him which he lost—at the tune of several million pounds.

And what I, there was a question asked of the politicians, and some of them responded with the kind of, what you would expect, or at least what I expected, which was a defense of the principle that we should all pay our taxes—our fair share related to what we were earning—and that to seek to avoid that through schemes and loopholes was a kind of a moral problem.

The problem for me was that the audience reaction seemed principally to be, “Well, you know, if you’re clever enough and you can afford a good enough lawyer to get you out of it, then we would all do that, wouldn’t we?” And that really worried me because it sort of signaled almost an acceptance of the idea that if you can get yourself out of your obligations, you should—or at least you can, and don’t get caught, right? But of those rich people and not of the people who are scheming off, you know, getting their benefits or something.

Social Movements and Environmental Activism

So, again, it’s the judgment of those that could do something. What’s going to say? One point I was going to make is, we’re about to see, I think, Saturday, there’s going to be, in Edinburgh and different cities, the Extinction Rebellion, and they say, “We will be arrested because we’re going to—it’s serious enough with climate change; we are going to block roads and cause public disorder.” And that’s an interesting development.

Identity and Inclusion

But the other point I was going to make was about our assumption that identity is based on inclusion. And maybe we see this with teenagers being othered. Defining yourself as other is an important, maybe developmental step, but it also might be an existential reality that people don’t want to be part of the society for whatever reason.

The Social Contract and Diverse Perspectives

Well, that was something you said, which I meant to get back to, which is really important—that there’s a kind of implicit assumption, again, in the liberal myth that there is a social contract that we’re all signed up to in theory. And of course, that’s an idea which is under—that was always a fiction, but even as a fiction, that’s under more and more intense pressure as diversity and disparity in views about what is a good life evolves.

Philosophers, interestingly, and moral psychologists argue about that, though there’s some work which suggests that for all that we frame our core beliefs in different ways, some argue that there are fundamentally common values held across cultural groups and different traditions.

Differences in Value Priorities

The thing is that they don’t prioritize them the same. So the one I remember always is that conservatives prize purity, which, purity as a cultural value—we all do. We all care about preserving in a kind of pure condition things that we regard as of profound value, whatever that is. As long as he’s not talking about race, well, it can be corrupted; it can be corrupted into that; it can also be corrupted in lots of other ways.

But purity has the idea that things that we hold good should be held good and should not be kind of transmuted by diversity. But the liberals will trump purity for freedom. So that the contest is over not having fundamentally different values, but having different priorities among values and different weighting. But, you know, that’s just one—he’s a moral psychologist and philosopher who takes a particular view.

The Enrichment of Cultural Diversity

I think cultural diversity, and I would see that as something that should be a cause for celebration, ought to be enriching. But it depends on our efforts to kind of live in more complex social groups which are characterized by difference. The attention that we pay to the dialogue and the conversation needs to be intensified because less can be taken for granted.

The Waning of Intercultural Dialogue

Whereas that pressure or the need for that has come at the same time as we’ve withdrawn the resources that would enable that sort of intercultural, interfaith dialogue to take place in ways which actually foster collective efficacy across diverse social groups.

Understanding Hate Speech and Societal Responsibility

But sorry, I’m trying to—yeah, I mean both at the one-to-one relational level and the social level. Like I said, if someone might casually throw out racist hate speech, I would be interested to know how that person has come to be that way. What is the social reality that that person has experienced that’s led them to be that way?

So rather than just viewing them or their action as bad in some sense, I think that society has a responsibility to inquire how that person has come to be that way. So in terms of reintegration, if that exploration isn’t done, then, like you described it, it could actually not really at best—at unconscious levels might not get to those underlying issues that that person has been touched by or wounded by or whatever it is.

Terrorism and the Root Causes of Violence

In which case what you might have, even at best, is a person who has kind of internalized that, whatever that was that drove that, suppressed it in order to be compliant. But actually, the more fundamental issue is unresolved, which is liable to create a vulnerability to—for that to resurface. I think a lot of the response that we make governs, for instance, this war against terrorism, which is becoming more and more surveillance; people getting interviewed by MI5, MI6, things like that.

I saw a couple of videos a week ago of people who’d been interviewed, and it was completely appalling the way that they were treated. They hadn’t done anything; they were just suspects because they met lots of criteria by which you could be a suspect. It seems obvious to me that if someone has actually committed a terrorist act, that you would say, “Well, what is the meaning of their behavior? What lies behind that?” It’s got to be grievance, hasn’t it, of some sort?

Grievance and Society’s Response

But there’s never—I don’t feel there’s any attempt to ask those questions so that we could better deal with those very legitimate grievances, I feel, that many people who’ve come here from the Middle East, not just Pakistan—yes, and I think the attitudes now that are becoming more prevalent is that people who ask questions like yours, you know, “What is that person’s motivation?” are seen as somehow reprehensible themselves, because they’re seen as somehow defending the crime, you know? And you get—it’s almost become an environment now where you can’t even ask those questions anymore, which is quite frightening, really, to me.

The Increasing Punitive Climate in Society

Who was it that said, “We need a little less understanding and a little more condemnation?” I think that was John Major or one of them. Well, I’m just interested in the cultural climate really and how you’ve experienced this. Because you’ve indicated that the punitive, retributive aspect seems to be on the increase.

I seem to see that in the media and in documentaries I’ve watched on TV, and is that really helpful? No, it’s not profoundly unhelpful; it’s counterproductive, but it’s the sociologists of punishment, who study that, argue that there’s no sort of settled consensus on it. In broad terms, the argument is that we’ve created for ourselves a less secure society, and there’s a sense in which, at one point, rising crime rates were part of the driver of that insecurity.

The Impact of Neoliberalism and Ontological Insecurity

In the postwar era, we expected the welfare state and the collective protections that we were investing in to produce peace and tranquility and falling crime—and it didn’t. So faith in the welfarist project waned, and instead we got neoliberalism. We have market deregulation, less protections for people in the workforce. At the same time, we have a decline in the certainties that were once associated with religion or with political ideologies.

People kind of lose faith in both senses, and they also lose faith in experts, in science, in progress—all of those ideas. So you get what Anthony Giddens calls ontological insecurity, which is to be insecure about the very nature of our being. We’re insecure in the labor market, we’re insecure financially, we’re insecure in multiple ways at once. And the consequence of that, so the argument goes, is precisely the atomization and individualization and self-protection that’s been generated.

The Erosion of Community Solidarity

So it’s a kind of ultra-individualistic effect which atrophies and damages social bonds, weakens community ties. We insure ourselves against risks; we don’t look after each other. You have to ask, “Where’s the solidarity?” Exactly. So you get, at the same time, there’s an argument that the state chooses that path economically. When you pull back from the welfare provision, you have to strengthen the penal system because that’s where you mop up. So you get less welfare, more punishment—in simple terms, as the price that’s paid for essentially a much more selfish and individualistic society.

Othering and Social Division

Then along with that comes othering, you know, the kind of separation of people into classes, groups, categories—even species. The notion of sort of subspecies, like “the cockroach migrant,” that kind of horrible language which is basically signifying finding—well, Judith Butler has this lovely, but also agonizing expression for it, which is she tries to understand how it is that some lives are grievable lives and some lives are not.

Addressing Grievability and Societal Anger

Yeah, so what’s happening that is allowing us to construct certain lives as grievable or not? And I think that’s very kind of—why aren’t we getting angry? Well, that’s a very good question. I actually think that those social processes also weaken the resistance because they make us all feel vulnerable and isolated, and they kind of undermine even the collectivization of opposition. So that’s probably part of it.

Exhaustion and Distraction in Activism

We’re also exhausted and distracted; we were talking about this earlier. We’re running around in circles, chasing our tails, consuming our time and energies and resources in largely fruitless pursuits. We’re kind of distracting ourselves to death. You could argue. So it’s hard to know what to do that would be effective. Also, I find myself marching at anti-racism rallies, but I kind of feel, “What difference is it going to make, you know?”

Collective Action and Resistance

But I tell myself, you should stand up and be counted in public space against racism. Yeah, well, I think—I mean, again, I think the answers are old answers. There’s consciousness-raising, there’s collectivization, there are small changes, there are individual steps, and there’s the pursuit of justice at every level, from the way that we relate to the individuals whose lives we’re most connected with, right through to the global questions of justice—and then how do we order our lives in ways which are sustainable and diminish the kind of waste.

Empathy and Social Responsibility

And by waste here, I’m not talking about environmental destruction; I’m talking about the waste of us as an ecology that could flourish but which, actually, most of the time, we self-pollute. Maybe I should just cover most of the Marxist protest in Scotland, so I really observe a lot of the dynamics around them. One thing I feel is that I feel more people need to invest in causes for the perception that they’re not an immediate beneficiary.

Investing in Social Causes for the Greater Good

I feel a lot of people are motivated to protest about things if it is immediate to them, but I don’t think that’s going to be enough. I think people have to have a much wider social sense in terms of the issues that they’re willing to invest in. So, consistently, this issue comes up, and I observe a lot of protests and movements.

The Challenge of Motivating Wider Investment

So how can society motivate people to have this wider investment? A challenge is that more people should be here tonight to hear about prisons. Really, it’s an important issue.

Propagating Empathy Through Storytelling

Well, I think one part of that might be thinking about how to propagate the seeds of empathy. If you’re trying to look beyond even an enlightened self-interest—politics of enlightened self-interest—then one way to do that, and one way to counteract the othering that we just talked about, is through deliberate strategies that are about the generation of empathy. I think in that connection, different strands of my work, narrative storytelling, and culturally mediated ways of connecting people whose experiences are disparate is profoundly important.

So a little advert—I’m involved in another project called Distant Voices Coming Home, which is a project that uses songwriting in Scottish criminal justice in and around people who are in prison or on community sentences, families, victims, people who work in the system, and people who study the system—all working with Scottish musicians to write songs that explore aspects of our experiences. Then we take the songs into public forums, from very small house gigs to very large public events, and we’ve got a headline slot in the Celtic Connections Festival on the 31st of January at the Queen Margaret Union, which is on the University of Glasgow campus, where we’ll be performing.

Engaging Through Public Performance

Not we; I won’t be performing. The musicians will be performing songs from that project. I think of that as a propagation of empathy—it is just a way of bringing lives that you don’t hear about into your consciousness in a way that is less easily ignored. There might be the beginning of something. And actually, I know there is because people who engage with that project and are moved and affected by those songs often do something about it. You know, they act.

Closing Thoughts on Empathy and Social Action

Right, we could go to our next event this Saturday in the F. We have a day conference on empathy education and the education of the heart. It’s an excellent lineup and a very good group there. So I mean that aspect of empathy deficit, I feel, that’s very much with some politicians. The policies they enact, but they’re not empathizing with the implications that that has.

A Personal Encounter with Empathy

That sounds like a good point to end on. I was going to tell you a very nice experience I had last week, which would be cheerful. I was asked by a young woman—she was collecting signatures to send a petition to the Home Office to enable refugees’ permission to work. You know how they come and they’re not allowed to work; they’re just given about £36 a week and expected to survive.

So I signed it, and then she said, “Could you take it and get it filled in?” So I said, “Okay.” It seemed a small thing. I sat myself down in Leaf, and within about 20 minutes, I had the sheet filled in. I never got any crap from anybody about too many immigrants or anything—they totally understood that we need to care for refugees.

Conclusion: An Encouraging Note on Empathy

So there is empathy among people; there is—totally; they were all total strangers. I didn’t know them; I just spoke with them. Well, that is a good and happy ending, small as it may be. Well, thanks very much for coming out. I really appreciate it, and it was fascinating to hear your thoughts and reflections.