The Union and the Collapse of Ragged Day Schools, 1861 – 1874

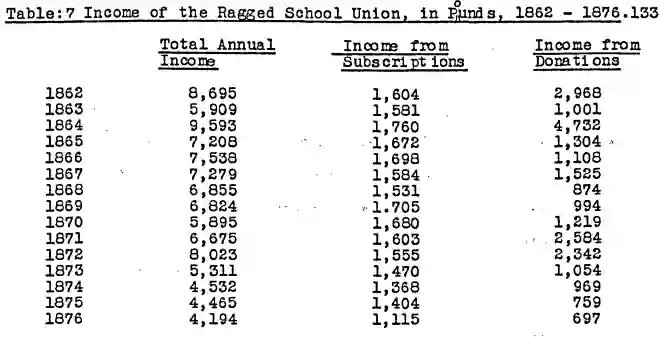

From the Report of the Commission to the Education Act, the Union continued to expand its enterprises, though the rate of acceleration was not as great as in the previous decade. It retained its characteristic of gauche eagerness, and this period differed from the previous one only in its emphases and conclusions. Its finances reached their peak.

(133. Abstracted from Ragged School Union Accounts, 1862 – 1876.)

The previous year’s income was due to the Union’s appeal to the public for support for its work. This raised £2,000. It felt that it would probably have got half as much again “but for the death of the Prince Consort” and “the appalling tragedy at Hartley Colliery.” These events “absorbed the public mind and took money which might have come this way” (134. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1862, p.15).

The reduction in income in 1863 was put down to “a year of trial and much distress.” This was a reference to the war in America and the poverty in Lancashire resulting from the cotton famine. At this time, “every religious and philanthropic society has felt its means reduced” (135. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1863, p.15).

Generous bequests raised the income of the Union to a record level in 1864, but even so, it was unable to meet all of the commitments it imposed upon itself. And in that year, it lamented that it “had never yet been able to help poor schools to the extent required” (136. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1864, p.15). At this time, seventy of the schools in association had debts totaling £2,500 (137. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1865, p.8).

In order to raise this money, it suggested in 1865 that clergy should take regular collections to support the schools and “extend these valuable Home Missionary operations.” The clergy did not respond. The income for 1866 was supplemented by legacies worth £2,550 (138. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1866, p.23).

However, a real financial crisis loomed when it appeared that proposed legislation would rate the ragged school rooms. The Union calculated that it and the schools together would have to find an extra £3,000 p.a. if this passed (139. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p.25).

They opposed it vehemently in Parliament and in their publications. Although the measure was not finally defeated, they were able to receive exemption from its provisions (140. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1870, pp.23-24). After the Education Act, its finances showed some fluctuation and declined, reaching only £3,500 in 1880 (141. Ragged School Union Accounts, 1880). It was a period of difficulty, involving change and redirection of resources and concerns within the Union.

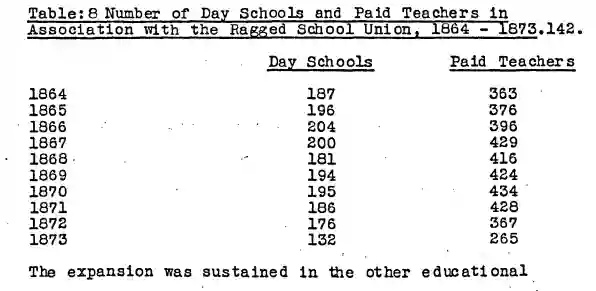

(142. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1864 – 1875.)

The day schools increased but more slowly than before. They were to be drastically cut back after 1872, but up to that time, they received considerable support from the Union. The expansion was sustained in the other educational areas.

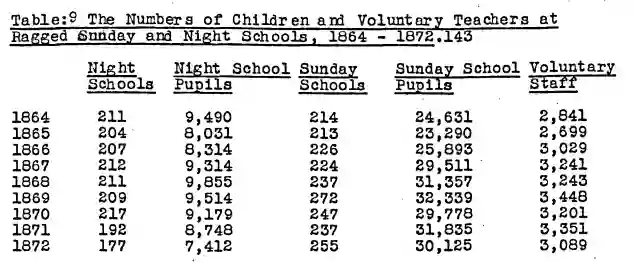

(143. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1864 – 1872)

The decline in the number of night schools and of the children attending them was due to the closure of day schools. One of the concerns of the Union was that premises which were given up or taken over reduced the voluntary work not connected with the day school itself by limiting the centres of operation (142. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1864-1875).

This had been a problem before the Act, for the demolition of the slums to make way for major rebuilding and for a new road system for London had meant some movement of population. It sympathised with the “suffering poor” who were “driven away” and “compelled to herd together in other localities.” Large families “had to find accommodation in a single room and that often a very small one” (144. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1867, p.7).

It was a perplexing problem for the Union. It noted that 1,500 houses had been demolished in notorious slum areas of Agar Town, Notting Hill, White Cross, Kingsland, Somers Town, Sloe Lane, and Brampton Field Lane, and regretted the loss of its institutions (145. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1867, p.7).

However, in the year that this happened, it was forced to take account of the unhealthy conditions under which people in these areas lived, for a severe cholera epidemic broke out. The premises of Nichol Street and Elder Walk Ragged Schools were turned into dispensaries and were open day and night. Little Denmark Street School acted as a cholera hospital. Teachers from the Union’s schools visited the sick and dying and distributed meals and medicines. Dr. Cross, one of its Committee members, wrote a paper advising practical preventive measures and recommending treatments (146. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1867, p.21).

The initial attitude of the Union to the thinking which was behind the new Education Act was one of aggressive self-defense. It used its not unfamiliar practice of dignifying its own interests with the name of principle. Much of its thinking was presented in rather stale evangelical clichés, which prevented those outside the Movement from giving proper weight to its arguments. Its prime blunder was a political one.

It underestimated the strength of those who wished for a national system of education financed from central and local funds; it overestimated what voluntaryism could do and failed to see that in view of the size of the problems, this philosophy was no longer relevant. Its major tactical mistake was to accept a missionary manifesto as a nostrum for all of the malfunctions within society.

It tried in vain to combat the theory that “secular instruction widely disseminated by a well-trained and skilful agency, but apart from Bible teaching by real Christians, will make a moral and well-ordered people” (147. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1868, p.5).

When it was apparent that Forster’s Bill would get strong support, it became hysterical and overplayed its hand by packing the court with too much partial evidence. It put itself in the position of having to defend the Bible and proclaimed its distress at a scheme of education which “excluded the Bible from state-supported schools – the best and purest literature we possess… (which) shut the Book which was the foundation of our morality and the charter of our principles as a Christian nation” (148. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1870, p.8).

It sought, without success, to incorporate into the Bill through its Parliamentary friends the following resolution: “In the case of all schools under the management of School Boards, the Bible, subject to the action of the Conscience Clause, shall be read at known and stated times” (149. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1870, p.9).

Other recommendations regarding the status of teachers in relation to the grants received by schools were unsuccessfully made. Once the Bill was through Parliament, the tone of the Union changed. It became more subdued as it felt the shock and realised how deeply this affected its own activities. A major re-adjustment was inevitable but could not be rushed in view of the procedures laid on the school boards before they could begin their activities.

By 1871, it was prepared to admit that the Act “in theory is an advance in the right direction, but the difficulty will be in giving practical effect to its provisions” (150. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.6).

But “it would have been glad if the new Act had settled the religious question by requiring the Word of God to be taught” (151. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.7). When it approached the London School Board, it was told that the following resolution had been passed: “That in the schools provided by the Board the Bible shall be read, and there shall be given such explanations and such instruction therefrom in the principles of morality and religion as are suited to the capacities of the children” (152. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.7).

This was a reasonable compromise given the parties and interests comprising the Board. The posturing of the Union had been unnecessary. It faced the prospect of the loss of the day schools and its influence there with a disappointed resignation. The best plan in the circumstances was for its friends to allow themselves “to be appointed by the Board to the management of local schools” and for voluntary teachers not “to consider themselves superseded by the new order of things” (153. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.9).

Understandably, some of the local committees of ragged schools, facing a difficult financial struggle, were not averse to handing over their schools. The Union correctly saw that the Board “will not, for a long time to come, be prepared to take over any of the present schools” (154. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1871, April, p.19).

Lord Lawrence, Chairman of the London Board, sent a letter to the Secretary of the Union, urging him “to relax no effort to maintain the schools in a state of efficient operations” (155. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1871, April, p.19). The Boards had statutory obligations to complete returns on which to base their decisions regarding educational provision for their areas.

In any case, it was recognised that “a large proportion of our schools must fail to be recognised as efficient, either as regards the state of the school buildings or as regards the standard of teaching” (156. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1872, p.6).

Thus, the Union determined to continue its day school operations for the time being, “though in no spirit of unfriendly rivalry” (157. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1872, p.6). It claimed that it had never sought to compete with other schools and stated that its day schools were always “tentative, to be superseded in due time by some effective and permanent arrangement” (158. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1873, p.7).

This was an attitude that took no note of the history of the Union and its previous principles, though it did allow that the “Society must adapt itself to the exigencies of the times.” (159. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1873, p.7). So it prepared itself for the loss of pupils and schools. By 1874, it had 72 day schools with 10,000 scholars. In its report for that year, it noted that after the Act, 26 schools with 3,000 pupils collapsed through the loss of support; 6 with 1,500 children became “pay schools”; and 39 were transferred to the Board with nearly 9,000 pupils (160. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1874, p.6).

Ten years later, it had only 35 day schools, with just over 1,200 children in association with it (161. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.12). These were schools “where the buildings and the teaching satisfy the Education Authorities and the Committee can obtain a grant” (162. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.12).

But it felt that “the system admits of no consideration being shown by the authorities for the class of backward children in attendance or the special difficulties incident to the work; the wonder is that the stipulated results are obtained” (163. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.12).

By 1873, the Union had re-appraised its role. It realised that “the secular work will probably become less,” but argued that “the religious, moral and social work” must continue (164. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1873, p.7). As an agent in ragged school education, its role was almost defunct.

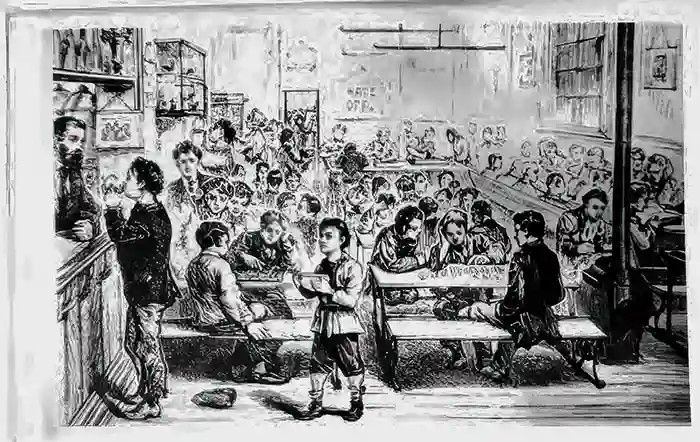

The Ragged Youths’ Institute, Latymer Road, London, 1880 Source County Hall, London

It had now only a temporary commitment to a holding operation. It realised that: “the changes already commenced will go on until the whole of the Day Schools have either been absorbed by the School Board or are compelled to alter their character so that they will no longer be institutions specially adapted to the needs of the ragged class” (165. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1874, p.7).

The Union’s interests turned towards the expansion of a host of auxiliary missionary and social services. In the 1880s and 1890s, a ragged school meant either a Sunday school—usually attached to an evangelical mission hall—or a centre of social welfare for the poor. “It has an elastic meaning, embracing, as it does, beneficent agencies for good” (166. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1883, p.5).

The London Ragged School Union was a paradox. It failed to respond to the challenge of the times. It fought misguidedly—failing to relate its principles to the larger perspective of a national education system—and unsuccessfully—by clinging to a view of politics and political action which derived from theological and not social or economic realities. Shaftesbury’s initial association, which had prompted much of the early success, became overbearing and resulted in the premature ossification of the Union’s thinking.

Provincial schools had a freedom from constraint in adapting to changing local conditions which London schools did not share. Technically, the Union was advisory and not directive in operation, but it wielded the power of the purse over institutions and schools that were always desperately short of money. The two crises in the Union’s history, in 1861 at the Report of the Newcastle Commission and 1870 at the passing of the Education Act, show how ill-prepared it was for newer ideas of education.

The intolerance of evangelical religion translated itself into educational theory; its blindness infected its educational practice; its partial insights limited cooperation with those of wider and more liberal views. Despite the endless conflict of the Union with the emergent secular god, despite the uncertainty and bitterness with which it had to change direction, it was a lively and dynamic body within the limits of its philosophy. It explored the ramifications of voluntaryism with an inventiveness and social awareness that brought relief to thousands of destitute children and their parents.

Practical provision was sensible, clear, and loving. The ideals and aspirations it adopted were interpreted within the Movement with flexibility and a caring insight. Its actions were characterised by a determination and energy that did not flinch from sacrifice. It showed a rare wisdom in encouraging its offshoots to establish an independent existence.

The root cause of the paradox posed by the Union’s sensitivity and tenderness to the needs of those within the Movement and its insensitivity to and lack of comprehension of those groups without lay in the fact that it had become Lord Shaftesbury’s intense and absorbing hobby. It reflected the complete spectrum of his political and religious ideas—and was pleased to do so. He had rapidly become the patriarch of the Union and flawed it with his own basic defect—the inability to perceive that reverence and devotion can be expressed in many and different ways.

Listed Bibliography of References:

133. Abstracted from Ragged School Union Accounts, 1862 – 1876.

134. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1862, p.15

135. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1863, p.15

136. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1864, p.15

137. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1865, p.8

138. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1866, p.23

139. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p.25

140. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1870, pp.23-24

142. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1864 – 1875

143. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1864 – 1872

142. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1864-1875

144. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1867, p.7

145. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1867, p.7

146. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1867, p.21

147. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1868, p.5

148. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1870, p.8

149. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1870, p.9

150. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.6

151. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.7

152. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.7

153. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1871, p.9

154. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1871, April, p.19

155. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1871, April, p.19

156. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1872, p.6

157. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1872, p.6

158. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1873, p.7

159. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1873, p.7.

160. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1874, p.6

161. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.12

162. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.12

163. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.12

164. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1873, p.7

165. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1874, p.7

166. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1883, p.5

This is the work of D.H. Webster who wrote a thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Leicester, 1973. It remains an important historical document and analysis of the Ragged School and free education movement in Britain. It will be reproduced and published verbatim in instalments for educational purposes to facilitate review and discussion about education. This post is the first part of section one of the thesis where the references have been reproduced inline within the text.

You can see the thesis overview and contents here:

The Ragged School Movement and the Education of the Poor in the Nineteenth Century