Education History: The American Chautauqua Education Movement

The Chautauqua movement was the most important of the popular free education movements in the history of the United States. So why is it not more known and talked about ?…

It was through the activities of the Chautauqua Institution that the world was opened to the isolated communities of the then new Middle West. Started for the purpose of training Sunday School teachers it rapidly expanded its offerings as popular demand came from thousands of culture starved communities and angry, inchoate movements of social protest.

From its genesis in 1874 it came to found and shape not only universities but the whole of American higher education. The Chautauqua movement was not a single, unified, coherent plan directed by a single individual or a group, it was, fundamentally, a response to an unspoken demand, a sensitive alertness to the cravings of millions of people for something better! (Joseph E. Gould, The Chautauqua Movement).

It was one of several waves of mass enthusiasm for self improvement, social betterment and reform which swept over the United States changing tastes, laws and social habits. The Chautauqua movement pioneered in correspondence course, lecture study groups and reading circles. It filled a vast need for adult education opportunities, mostly in the rural regions of America

Chautauqua and its emulators also provided a free platform for the discussion of vital issues at a critical time in history. The movement also brought about high standards of cultural entertainment, book learning and lectures in a way we struggle to grasp today, even though materials and resources are more abundant.

The movement introduced many new concepts and educational practices into America: university extension courses; summer schools; civic music and civic opera associations; Boy Scouts, Camp Fire Girls, and similar youth groups; courses in dietetics, nutrition, library science, physical education; and a university press…

Dozens of such ideas germinated in the minds of liberal-thinking Americans, were given their most vigorous and effective support from Chautauqua platforms. Brilliant and well informed men and women lectured to avidly listening crowds on such topics as the conservation of natural resources, the eight hour day, women’s suffrage, pure food and drug legislation, national forests and parks, slum clearance, city planning, direct election of US senators, regulation of interstate commerce and the cooperative movement.

Frederick Lewis Allen called this period The Great Change and the vigour of the Chautauqua movement declined after the First World War, as we saw with women’s suffrage.

Birth of the Movement

In the hills of south-western New York State, just before they descend sharply to Lake Erie, there is a lake named Chautauqua. In the summer of 1874, two middle aged men started what we would call a camp at Fair Point on Chautauqua Lake and without meaning to, created one of the most vigorous private movements in popular education the world has ever seen

John Heyl Vincent was a clergyman who had never attended college as a resident student. He became the secretary of the Methodist Sunday School Union in 1868 where he established the Sunday School Quarterly a journal devoted to the promotion of higher standards in Sunday School teaching.

Vincent was concerned with the problem of securing good Sunday School instruction from untrained and sometimes unlearned laymen and women, and he put forward the formation of Sunday School Institutes. Intensive short term courses for religious teachers comparable to the Normal Institutes which many communities were holding for public school teachers at that time.

Working with Lewis Miller, a prosperous Akron manufacturer who was passionate about Sunday School teaching, they designed and built a Sunday School hall for the First Methodist Church in Akron. The idea was widely copied and the two men started to work together in the scheme of a protracted normal institute.

They chose the spot on the short of Lake Chautauqua and pragmatically set about their task. The first assembly opened at Fair Point on Chautauqua Lake on 4th August 1874 and went on for 2 weeks. In addition to instructional classes, Dr Vincent had planned an elaborate recreational program.

Light-hearted games were skilfully mixed with inspirational lectures by the famous personality John B. Gough. Dr E. O . Haven of the newly founded Syracuse University, lent an academic flavour to the proceedings, and the evenings were filled with concerts, illuminations and firework displays.

Dr Vincent wanted to secure a celebrity for his 1875 assembly where he invited Ulysses Simpson Grant, 18th President of the United States. Grant accepted the invitation and arrived in Jamestown on Saturday August 14th to stay the weekend of Chautauqua.

Fifteen thousand people turned up to greet the President as they seemed to form itself into one mammoth handkerchief and one throat that sent up shout after shout Helena M. Stonehouse; One Hundred Forty Years of Methodism in Jamestown.

1876-1877 were years of steady growth enrolment more than doubling each year. Hebrew then Greek were added to the curriculum. On August 10, 1878 Dr Vincent announced to the ready 1500 attendees of the 5th Annual Chautauqua Assembly his plan for the formation of a study group which would embark on a 4 year program of guided reading.

This group was called the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle and 200 people signed up in the first hour. More than 8400 people most of them from the new states of the Midwest, joined circles in 1878. Within ten years the enrolment climbed to 100,000 and at least that many more had either dropped out or completed their 4 year course. Zona Gale described the eagerness with which people were taking up free education…

I remember sitting silent on a little carpet-covered stool and listening to a women relate to my mother a part of the epilogue to the American Revolution… And, look here, in the first place they never wanted to unite at all! No Sir ! Some of em said it was impossible the colonies should ever be got to unite. Yes, Sir! And when they first talked it, to a meeting in Albany, only seven colonies sent delegates and nobody much but Benjamin Franklin was what you might say hot for it. Did you hear of such a thing? But the Govener of Massachusetts, he wanted it in order to fight France.

And say ! The folks in Virginia, and Georgia and South Carolina most fit over using the Savannah River. And Mrs Gale, when them British troops came over they tented em in Boston Common, and our book says Samuel Adams got up in the Old South Church and he says this meeting can do nothing more to save the country… wait til I tell you ! That was when we dumped the tea wasnt it grand ? …all her facts had been unknown earth until the Chautauqua American History had opened to her.

And now gossip, domestic grievances, prices had all been dropped from her conversation… all the stimuli were there the love of learning, latent in the pioneer and waiting, the mellower time when it might flower, the social urge to work together; the zest of competition in the race for seals and courses completed, and tenderest of all, the dumb desire to keep up with the young folk, already coming home from school with challenging inquiries. Zona Gale Katytown in the Eighties Harpers, August 1928, page 288

In an incredibly short period of time, nearly every community of any size in the United States had at least one person following the Chautauqua reading program. Iowa had more than one hundred circles in 1885.

Travellers reported finding train crews on Western railroads who had constituted themselves a circle. There were crossroad storekeepers who petitioned their grassroots philosophers to join the movement of free knowledge giving form and purpose to the informal conversations.

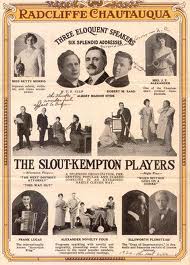

The Chautauquan monthly magazine was established by members in 1880 quickly gaining a circulation rivalling the most popular magazines of the day. Assemblies, sometimes called little Chautauqua’s began to spring up all over the Midwest. They varied in size, program and denominational (or other) sponsorship, but they all shared common features of working together to deliver free education through collaboration.

Hundreds of self styled Chautauqua’s were founded by private groups, communities, and religious denominations benefited by this association although in point of fact none of them was ever in any sense a branch of the original. The directors of the independents found lecturers, discussion leaders, and teachers among the holidaying faculty members of college and universities. Many enjoyed the prestige of the communities with whom they shared their time as they all shared an enthusiasm for learning and a distrust of economic and social panaceas.

Many communities were lacking in the most rudimentary amenities and cultural link with the East was out of the question; only the mining communities that had struck it rich could afford to underwrite the cost of Eastern talent. The homesteader’s land was held in fief to a bank or a railroad, and the true lords of creation were the Eastern magnates for whose benefit the land and the people were being exploited.

Unlike the pre-civil war pioneer in the old Northwest Territory, who was politically, economically and socially the equal of his fellow countrymen in any other region, the homesteader felt himself the victim of the banks, the railroads, and the trusts.

As a backdrop, Alexis DeTocqueville found the American pioneer of 1830 anything but culturally impoverished… he is, in short, a highly civilized being who consents for a time to inhabit the backwoods… It is difficult to imagine the incredible rapidity with which thought circulates in the midst of these deserts. I do not think that so much intellectual activity exists in the most enlightened districts of France… Alexis DeTocqueville, Democracy In America (New York: Knopf, 1947), I, 317.

The Chautauqua movement offered the discouraged settlers of the new West a link with the heritage they felt they had lost. The books and the lessons widened the narrow circle of their lives, and they sought to find in their courses of study a set of unchanging principles that could guide them through their difficulties.

The Chautauqua movement grew into a grass roots movement which was to give hope and dignity to the hitherto frustrated ambitions of hundreds of thousands. It guided and stimulated them in their desire to grow, and encouraged them to build for themselves free forums for the discussion of subjects of vital interests and for the production and introduction of new and exciting ideas.

A good book on this important piece of history is The Chautauqua Movement by Joseph E. Gould. It is a thorough documentation of all its aspects from start to finish. Special thanks go to Steve Tilley in highlighting this history to the Ragged project, thus showing that free education emerges in all cultures when there is a need for growth and better living standards. Steve is a sage voice and a champion to many causes such as Mad People’s History.