Educational History: Rabindranath Tagore 1861 to 1941

That education is a living, not a mechanical process, is a truth as freely admitted as it is persistently ignored (lecture in Calcutta in 1936 quoted in Dutta and Robinson 1995, page 323)

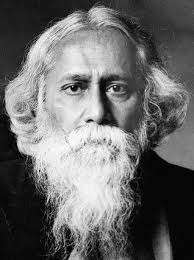

In 1940 Oxford University awarded an honorary doctorate on Rabindranath Tagore for all of his achievements, including those as an educationalist. He won the 1913 Nobel Laureate in Literature because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the literature of the West. Amongst many things he was a poet, writer, composer, painter, philosopher and educator.

From the questions that have often been put to me, I have come to feel that the public claims an apology from the poet for having founded a school as I in my rashness have done. One must admit that the silkworm which spins and the butterfly that floats on the air represent two different stages of existence, contrary to each other. The silkworm seems to have a cash value to its favour somewhere in Nature’s accounting department, according to the amount of work it performs. But the butterfly is irresponsible.

The significance which it may possess has neither weight nor use and is lightly carried on its pair of dancing wings. Perhaps it pleases someone in the heart of the sunlight, the Lord of colours, who has nothing to do with account books and has a perfect mastery in the great art of wastefulness. The poet may be compared to that foolish butterfly. He also tries to translate in verse the festive colours of creation. Then why should he imprison himself in duty ? Why should he make himself accountable to those who would assess his produce by the account it would earn ?

I suppose this poet’s answer would be that, when he brought together a few boys, one sunny day in winter, among the warm shadows of the tall straight sal trees with their branches of quiet dignity, he started to write a poem in a medium not of words (Tagore 1961 b, Pages 285-6).

Tagore’s family was very wealthy with a long history of artistic involvement. His grandfather Dwarkanath Tagore was a landowner and entrepreneur, his family being one of the first to profit by trading with the British. Dwarkanath was one of the richest men in Calcutta and was renowned for the extravagance of his pleasures, his rejection of religious orthodoxy, his philosophy and his funding of science based higher education for Bengali’s in Calcutta and the United Kingdom.

He was one of the first Hindus to be celebrated in European culture where he was known as Prince Dwarkanath and entertained the likes of Queen Victoria and Charles Dickens. Rabindranath Tagore’s father, Debendranath Tagore similarly lived like his father Dwarkanath Tagore in an indulgent and flamboyant lifestyle until the death of his grandmother on the banks of the Ganges at Benares. He was then to renounce worldliness to search for enlightenment in the sacred literature’s of the world. He revived a movement of reformed Hinduism called Brahmo Samaj and it was very influential in Indian education. He was referred to as the Maharishi or Great Sage.

Rabindranath again was very unique in carving out his own destiny. He was awarded the Nobel prize in 1913 for his work Gitanjali, a collection of verse in which he writes Deliverance is not for me in renunciation… I feel the embrace of freedom in a thousand bonds of delight. His childhood was one which he was bound to the institutional norms of privilege. He was confined entirely to school and the Tagore mansion in north Calcutta where he was educated under the control of generally harsh servants with a punishing schedule of private lessons.

He rarely saw his parents and he attended four schools over seven years. He finished this period with a complete lack of distinction in studies and memories which were not the least sweet in any particular (Tagore 1991 page 71). He developed a commentary on his early experience of schooling and rote learning before he decided to start his own school. He ignored his formal education and turned to creative members of his family. (The Vicissitudes of Education in Tagore 1961 b Page 41).

He wrote poetry in Bengali and English, and wrote under a nom de plume of Thomas Chatterton. His writing further developed after a year in the United Kingdom where he attended classes at University College London. He became convinced that Indians needed to be educated in both the best of their own traditions, the best of Western traditions and the best of the far Eastern traditions. This cosmopolitan perspective is resonant of both his father and grandfathers view, and it came to be the animating spirit of his university Visva Bharati.

Tagore wrote Let me state clearly that I have no distrust of any culture because of its foreign character. On the contrary, I believe that the shock of outside forces is necessary for maintaining the vitality of our intellect

He stood as a force for inclusion and representation which would amply stand beside the great syncretic (synthetic-eclectic) philosophers Cicero and Polybius…

What I object to is the artificial arrangement by which this foreign education tends to occupy all the space of our national mind and kills or hampers, the great opportunity for the creation of new thought by a new combination of truths. It is this which makes one urge that all the elements in our own culture have to be strengthened; not to resist the culture of the West, but to accept and assimilate it. It must become for us nourishment and not a burden. We must gain mastery over it and not live on sufferance as hewers of texts and drawers of book learning (The Centre of Indian Culture, Tagore page 222-3)

Rabindranath’s vision strongly influenced the British educated Jawaharlal Nebru, India’s first prime minister later became chancellor of Visva Bharati when it was incorporated as a national university in 1951. Jawaharlal Nebru sent his daughter Indira to study at Shantiniketan in the 1930s. Tagore’s vision permeated Indian culture catching the attention of the likes of mahatma Gandhi who sent a group of boys from South African Phoenix school to Shantiniketan prior to his own return to India in 1915. He later was to help raise money for Visva Bharati which always suffered from underfunding. Gandhi and Tagore had their differences in educational perspective in that Mahatma rejected the emphasis on science and the arts suggesting that Indian rural education should be primarily vocational.

Tagore said Education specially labelled as rural education is not my ideal education should be more or less of the same quality for all humanity needful for its evolution of perfection in a letter to the agricultural economist Leonard K. Elmhirst (Letter to Elmhirst, 19 December 1937, in Dutta and Robinson 1997 b page 491).

Leonard Elmhirst was one of the many talented scholars who worked with Tagore at Shantiniketan in the 1920s and 30s. Elmhirst went on to found his own educational institutions in the West a school and college at Darlington in the Devon countryside of Southwest England; this was directly inspired by Tagore. Dartington, like Shantiniketan, educated people by giving them as much freedom as possible, by exposing them to nature at every opportunity and by accenting the arts, especially music. This was in huge contrast to the scholastic and games playing priorities of British schools of the time.

Tagore and Elmhirst also aimed to make central in students minds and hearts, a respect for other cultures a radical contrast to the imperial ethos of the official British system and the derivative ethos of its Indian equivalent. Tagore’s vision was truly inclusive reaching out and drawing together disparate worlds.

“there was no aspect of human existence which did not exercise some fascination for him and around which he did not allow his mind and fertile imagination to play. Where, as a young man, I had been brought up in a world in which the religious and the secular were separate, he insisted that in poetry, music, art and life they were one, that there should be no dividing line” (Quoted in Introduction to Rabindranath Tagore, The Religion of Man, London: Unwin Paperbacks page 4 1988)

The economist, philosopher and Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, was a schoolboy at Shantiniketan in the 1940s. His grandfather was one of Tagore’s earliest teachers. Sen recalls his time at Tagore’s school as being rather important in making him aware at an early age that a worthwhile life requires variety and that narrowness of view is deadening. Sen particularly recalls starting a night school with other teenage students to teach local villagers the three R’s, which was possibly the beginning of his lifelong adult concern with literacy programmes. (Amartya Sen in Sian Griffiths (ed) Predictions: 30 Great Minds on the Future, Oxford: Oxford University Press page 214, 1999)

Satyajit Ray, great Indian film director of the 20th century was a student at Visva Bharati in the 1940s. He said in his later life that it was Shantiniketan where he first came to appreciate there was more to art and culture than the art and culture of the west which he was taken in during his college days in Calcutta. Shantiniketan opened windows for me. More than anything else, it… brought me an awareness of our tradition, which I knew would serve as a foundation for any branch of art that I wished to pursue (Quoted in Andrew Robinson Satyjit Ray: the Inner Eye; Andre Deutsch Page 55 1989)

Tagore’s ideas cannot be formulated and reduced to rote maybe this was his genius in that he never worked outwith the vision that knowledge and people are dynamic and emergent rather than fixed. He wrote many heartfelt and rational essays on education as well as textbooks for children, however he wrote no concrete theory of education bar maybe the statement I merely started with this one simple idea that education should never be dissociated from life (Letter to Patrick Geddes 9th May 1922, Dutta and Robinson 1997 b Page 291).

This implicit connection with the social and caring nature of being with that learning forged strong connections with Maria Montessori, another great educator. Montessori wrote to Tagore:

I feel that your people have achieved a higher degree of capability for feeling and sentiment than the Europeans, and I am certain that my ideas which are founded only on love for the children would find a good welcome in the hearts of the Indian people. This was eminently true…

Tagore replied to her saying the Montessori method is widely read and studied not only in some of the big cities of India but also in out of the way places; the method is, however, not so extensively followed in practice largely owning to the handicap imposed by the officialised system of education prevalent in the country.

Montessori traveled to India in 1939 and visited Shantiniketan where the two were immediately connected by their world view and educational philosophy. She knew that to a great extent Shantiniketan depended upon the unique driving spirit of it’s founder Rabindranath Tagore. They had a profound connection and this can be demonstrated in what she told Rabindranath’s son on hearing of his death in 1941:

There are two kinds of tears, one from the common side of life, and those tears everyone can master. But there are other tears which come from God. Such tears are the expression of one’s very heart, one’s very soul. These are the tears which come with something that uplifts humanity, and these tears are permitted. Such tears I have at this moment (letter 207 and notes, Dutta and Robinson 1997 b Page 291 Dutta, Krishna and Andrew Robinson, Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad Minded Man, London: Bloomsbury, 1995)

Further Reading:

http://www.ijcrar.com/vol-4/T.%20Pushpanathan.pdf

http://www.ibe.unesco.org/International/Publications/Thinkers/ThinkersPdf/tagoree.PDF

http://www.arvindguptatoys.com/arvindgupta/tagore.pdf

http://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/UF/00/09/81/23/00001/tagorehiseducati00jala.pdf