Ethnocentrism and Country of Origin Effects: The Process of Purchasing by Doreen Soutar

The early models of purchasing behaviour were developed in the 1970s, and were informed by research in psychology into the relationship between the individual’s intention to act and their subsequent behaviour (Fishbein & Azjen, 1975).

These models relatively simplistic, suggesting that behaviour was a result of a reasoning process which took internal thought processes and external influences into account. As these models were applied to purchasing decisions and expanded, it became clear that purchasing decisions were only partly rational, and contained a much wider and more complex interaction of influences.

Early models of purchasing decisions: Reasoned Action and Planned Behaviour

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) was developed by Fishbein and Azjen (1975) as a way of modelling decision making processes in the field of psychology. It is a very simple and concise model of the main aspects of decision-making, and asserts that a behaviour results from the combination of the individual’s attitude towards the behaviour, the subjective norm of their external circumstances, and their behavioural intention (Fig.1). An individual’s attitude and subjective norm represent the current state of belief about how acceptable or positive any given behaviour might be. Fishbein & Azjen (1975) asserted that the best predictor of a person’s behaviour is to look at their intention in context of internal and external pressures. As a rule of thumb, the more positive the behaviour is viewed internally and externally, the more likely the person is to perform the behaviour.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) elaborates on the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fig.2) by adding in the level of perceived behavioural control. This takes into account the tendency of the person to be influenced by their social or cultural external influences, and how likely the individual is to comply with external norms, or to behave more in accordance with their internal attitudes and beliefs.

Purchasing Behaviour modelling

These psychological models of Fishbein & Ajzen (1975) and Ajzen (1991) were adopted by marketing theorists as a basis for looking at the purchasing behaviour of individuals. Kotler’s Model of Buyer Behaviour refers to these models and expands on them. The ‘buyer characteristics’ and ‘other stimuli’ aspects are similar to that of the TPB’s subjective norm and attitude aspects. Kotler (2000) also expands on the external aspect of purchasing behaviour by adding in the element of marketing stimulus, a purchasing decision process, and a range of decisions which need to be made by the customer about what type of purchase they intend to make.

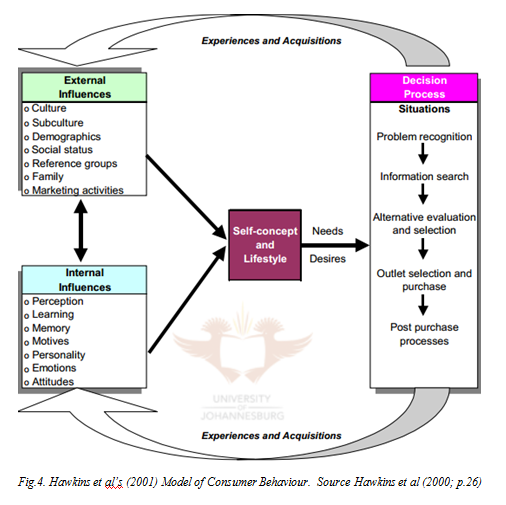

Similarly, Hawkins et al (2001) developed on the original notions of TPB and TRA (Fig.4). Here the internal influences involve both cognitive and emotional aspects which influence the decision-making process in terms of previous experiences and acquisitions. These internal influences are separated from the immediate needs which drive the individual to make the decision to purchase and the purchase decision-making process. External process in the Hawkins et al (2001) model are bundled together cultural, social, and marketing activities, and this suggests that Hawkins et al (2001) feel that external processes do not have the same level of influence as Kotler’s (2000) model.

So what Hawkins et al (2001) are saying is that an individual has a memory of previous purchases, and this memory influences how the person feels about making the same purchase again. External influences do have an effect on the type of purchases the individual is likely to make, but these influences revolve around the lifestyle and self-concept of the individual. That is, an individual’s belief about the type of person they are is critically important to their purchasing decisions, and these beliefs are at least partly based on previous decisions to purchase.

Hawkins et al (2001) expanded this model to include situational influences and financial resources to this model. However, the basic model serves to demonstrate the dynamic and repeatable process of purchasing whereby customers build up personal experiences of their purchasing preferences in a cyclical way. Both Hawkins et al (2001) and Kotler (2000) note that the individual’s perception is highly subjective and selective. That is, customers are unlikely to be able to pay attention to all the information they receive, so they use a filtering process called ‘selective perception’ to filter the information they feel is most relevant to them, and process it in a way that suits them (Kotler, 2000). Hawkins et al (2001) suggest that an information processing model for selective perception goes through a process of exposure to information, paying attention to the information, interpreting it, committing it to memory and then using this information to make purchasing and consumption decisions (Fig. 5).

As can be seen from the information processing model, processing the information an individual believes may be relevant to them is a complex interaction between exposure from the external environment and the internal subjective decisions as to whether to pay attention to it. So, for example, dog owners may pay more attention to marketing efforts for dog food than they would for cat food, because they feel more involved with that subject.

The involvement of memory in this process is important, as the individual’s decision to pay attention to an external stimulus can depend on the contents of memory. This includes previous experiences, values, attitudes, beliefs and feelings stored in long term memory as well as the immediate needs and desires of the person stored in working memory (Hawkins et al, 2001). Working memory is the part of memory which is currently in use for short term thoughts such as a mental shopping list (Eysenck & Keane, 2000). Therefore, for example, the items on a weekly grocery shopping list will be a product of both long term and working memory: preferred tastes or brands may be stored in long-term memory, whilst short term memory holds the information of current supplies of that item.

However, it is important to note that although short term memory tends to be conscious, the contents of the long term memory store is not all available to the individual’s conscious awareness (Hawkins et al, 2001). Therefore, one of the complexities of explaining how customers make purchase decisions is that the customers themselves may not be able to adequately explain their preferences.

Hawkins et al (2001) also dissected the component parts of an individual’s attitude to a product (Fig.6). According to Hawkins et al (2001), attitudes consist of cognitive, affective, and behaviour components. The cognitive component is comprised of the person’s beliefs and knowledge about a product. The affective component is the emotional feelings about a product, such as associating the smell of bacon with happy Sunday morning breakfasts. The behavioural component is the level of effort an individual is prepared to make in order to acquire a preferred product, such as chocolate or coffee (Hawkins et al, 2001; Zikmund, 2000; Kotler, 2000).

An individual’s attitude is considered by Hawkins et al (2001) to be a combination of the affective and cognitive components. This means that the person’s overall attitude to a product is a combination of their beliefs and feelings about a product. Each product considered by the consumer will have its own unique blend of cognitive and affective issues which motivate behaviours (e.g. Kim et al, 1998) and the individual’s personality will play a role in deciding whether their cognitive or affective influences influence behaviour more or less (e.g. Brassington & Pettit, 1997).

Kempf (1999) notes that attitudes towards products or services are often formed through direct experience, and the difference between the memory and attitudes towards good and bad experiences will be discussed in a further section. However, Kirzner (2001) and Lovelock & Wright (1999) argue that direct experience is not a necessary component to attitude formation.

Purchasing Motivation

An individual’s motivation can be described as a drive towards a particular behaviour which will satisfy a desired need or want (Brassington & Pettit, 1997). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs distinguishes several levels of need, beginning with basic physiological needs of survival, such as hunger or thirst, then safety needs to secure survival, social needs are those which fulfil a sense of belonging, esteem needs are those which involve status or recognition, and self-actualisation needs are those which feed into a sense of self, and the construction of a set of values (Brassington & Pettit, 1997). Maslow (1943) suggested that these needs are hierarchical, because each need can only be addressed if the one below it is fulfilled. So, for example, it is unlikely that esteem needs for status and recognition are likely to be greater than those for safety and physiological needs. Kotler (2000), amongst others, suggests that once a need has been fulfilled, motivation disappears. Engel et al (1995) suggests that some motivations are in constant need of fulfilment, such as food and drink. Hawkins et al (2001) note that more than one type of need may be fulfilled by a single product, so that for example, buying Fairtrade coffee may not only fulfil the physiological need of thirst, but also feeds into esteem needs and value needs (e.g. Bondy & Talwar, 2012).

Customer Equity and Non-Rational Purchasing Influences

Emotions can also be a powerful motivator (Bagozzi et al, 1999; Zeithaml & Bitner, 1996). Emotions are defined by Hawkins et al (2001), amongst others, as physical experiences such as changes in blood pressure, blood sugar levels, and heart rate. These are uncontrollable, internal physiological changes and tend to be triggered by influences in the individual’s external environment. Rust et al (2000) assert that aspects of a product such as brand equity are not simply a conclusion reached by the customer about which product provides the best value for money. On the contrary, there is also an emotional and non-rational set of decisions that the customer may not be conscious of. Indeed, although customers may justify their purchases in terms of rational reasons in hindsight, the underlying psychological principles are not so simple (Rust et al, 2000).

In seeking to understand the various influences on purchasing decisions, Cardy et al (2007) defined customer equity as being comprised of three elements: value equity, brand equity and retention equity. Value equity is the rational decisions a customer makes on the worth of the product, such as the quality of the materials and the construction, the price, the customer’s need for the product, and so on.

Brand equity is concerned with the emotional desirability of the product. According to Holt (2004) a brand contains a form of story or identity myth that customers buy into when they purchase the product, whether it is to do with the inherent value of the product or a lifestyle choice of the individual.

Retention equity is the ongoing, dynamic relationship between the person and the product over a period of time. Customers may decide to remain with a familiar product rather than switch to a substitute even when the substitute may represent better value on a rational level.

In addition, Cherrier (2009) suggests that consumers can use their purchasing preferences to express political preferences. Cherrier (2009) discusses the influence of ‘anti-consumerist’ subcultures, where individuals prefer to view themselves as being outside the dominant consumerist norms, and have a tendency towards resisting “mass-produced meanings” (Penaloza & Price, 2003 (p.123) in Cherrier) which accompany the stories produced by brands.

However, there is a gap between purchase desirability and intention, and the actual purchases consumers make. In research into factors contributing to ethical consumption, Bray et al (2011) discuss Kim et al’s Attitude/Behaviour Gap (Kim et al, 1997 in Bray et al). The Attitude/Behaviour Gap shows that the number of people who considered themselves to be ‘ethical’ purchasers was not equal to the number of customers purchasing ethical goods. Kim et al’s (1997) conceptual framework for the reasons for this gap suggested issues such as price, inertia, limited availability, and scepticism (Fig. 7).

Bray et al (2011) used this conceptual framework to research actual impediments to ethical purchasing by using focus groups. Their results showed that there are eight key elements: price sensitivity, experience, ethical obligation, information, quality, inertia, cynicism, and guilt (Fig.8)

Notably, Bray et al (2011) found that the effort required to source ethical products and their limited availability had been an issue for Kim et al (1997), but no longer appeared to be important. However, Bray et al (2011) found that more consumers felt under an emotional obligation to purchase ethically, and suggested that purchasing products which were less socially acceptable may result in post-purchase cognitive dissonance and guilt (Hiller, 2008 in Bray et al).

Bray et al’s (2011) results were obtained in the specific instance of purchasing products with an ethical supply chain. However, it may be possible to widen these results to suggest that consumers are aware of the social acceptability of purchasing decisions, and that social norms do indeed play an important role in types of purchase. However, it also suggests that this awareness may play a role in the willingness of consumers to be completely truthful about their purchasing reporting to researchers. Bray et al (2011) used focus groups to address the issue in a qualitative way, so that participants could discuss issues of social norms of purchasing and post-purchasing dissonance. These results may not be replicated by quantitative researches such as surveys, as respondents may not wish to ‘confess’ their socially unacceptable purchases, preferring to project their ideals rather than their actual behaviour.

Section Summary

Research into consumer purchasing behaviour began with simple, psychological models such as the Theory of Reasoned Action (Azjen, 1991), which showed that there are two primary issues in the process of making a purchase: internal attitudes and external influences. Subsequent research into internal attitudes has shown that the purchasing decision-making process involves complex cognitive elements, such as previous preferences and current needs. The internal process also includes an emotional or non-rational element, where the consumer expresses their preferred self-image through brand association, and demonstrates feelings of affiliation through brand loyalty, for example. These internal elements also interact with external elements such as social norms and brand messages. These messages can be very powerful, and whilst they may not ultimately dictate personal purchasing decisions, differences between personal purchasing decisions and social norms may result in feelings of post-purchase dissonance and guilt.

Link to Previous Section

Link to Next Section