Action Research: Local Knowledge and Building Dialogue

This is the next installment of my action research project which has been examining the effects of the organisational bureaucracies and administrative systems on the lives of people who have to live in and under support services.

You can read the previous section of this project ‘Action Research: Demoralisation Through Down Sourcing’ by clicking HERE.

This part of the research project discusses how knowledge from outside the professional and ‘authoritative’ circles is vital for apprehending the world as it. It explores what happens when peoples voices and experiences are devalued or unvalued in the context of the need for vital information to act appropriately in specific situations.

Typically we see situations being governed by a group of people invested in a vision of hierarchy which excludes those who sit outside of the hierachy or distant from their position within one. Corporate structures – aka large groups of policy organised people – are riddled with silences which can represent many things. The propensity for people not to acknowledge things which sit outwith their comfort zone of agency and willingness is a key issue in causing ills to continue within line managed systems.

Budget, finance and profit is used to magic away the damages, harms and negative externalities of organisations – civil, third sector and private – by creating cyphers on paper or administrative documents. The special feature of this kind of behaviour is that once an expression of a reality has been rendered in print, all the aspects of that reality which are not included in said print become collectively and remotely viewed as non-existent. In this way what the doctor does not write is not treated as having substance, what the civil servant fails to document is treated as not having happened, what the support worker omits in detailing cannot be called on in account.

Co-creating accounts is an issue which we see in the face of dominant bureaucracies in hierarchical societies; this is largely because for many reasons accounts become rendered by the person at the top of the power juncture: in the support/need juncture this is the person who is being paid. Miranda Fricker describes hermeneutical injustice as where ‘someone has a significant area of their social experience obscured from understanding owing to prejudicial flaws in shared resources for social interpretation’.

Fricker, M. (2011). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Understanding how we can deal with the hermeneutic injustices which are distributed throughout our administrated society is critical to creating a society which functions better. The article below examines how approaches in existential phenomenology might be helpful in coordinating fuller pictures of what people are encountering in their lives that they need support. Many people need support because it is an unfair society which in many cases rewards unfair behaviour towards others. This is partly why I conduct this investigation in respect to our societal structures.

Preamble:

Before each installment of the outcomes and measurements analysis of theory and practice I write a preamble to add flesh to the contexts which outcomes and measurements bureaucracies are applied – i.e. the living situations of people’s lives. For some these preambles my seem unnecessary deviations in the discussion of administrative instruments like the Outcomes Star – commonly applied to multiple support settings in order for organisations to get bankrolled by people who guard coffers.

The reason for these added commentaries is to attempt a partial reversal of what Kimberly Crenshaw identifies as how people become “theoretically erased” in the siloed way that accounts are administrated in order to allocate support. To contextualise this, let us think about the people who live with multiple needs; a series of supports are needed for them to live a healthy normal life, and when those needs are met many of the issues they have dissipate as their wellbeing and capacity improves when their needs are met.

Problems come when each need is viewed, administrated and met in siloed ways – for example, mental health needs are dealt with by one agency, housing needs are dealt with another, substance use issues are dealt with by a different structure and so on. Then multiple agencies and structures are all operating within that persons life, none of which are taking into consideration the fact that all these needs are inextricably linked – their job is to focus on one need and not the other.

In our example, poor housing or lack of it may be causing mental health deterioration and as a result someone may have started drinking and self medicating for the stress, poverty and uncertainty. Each problem has become mutually reinforcing and staggering piecemeal approaches often become a problem in themselves creating a sense of futility and hopelessness for the person at the mercy of them.

Each agency and support structure then creates its own set of outcomes and administrations which ultimately get downsourced into the life of the individual who has to negotiate a series of specialised jargons and machinations (without any training). Often the jargon of ‘person centered planning’ is used but there is no interdisciplinary working going on so that person ends up doing several ‘person centered plans’ with agencies and structures which are all pitted against each other each year (or more frequently) for pots of money and ultimately putting funders administrative desires at the center of the plans.

The people on the front lines have limited amounts of time allocated which they can spend supporting each ‘client’, and their efforts are allocated according to the budget of the organisations rather than the time needed to resolve or make a stable positive difference. For example, General Practitioner doctors have ten minute time budgets to deal with each appointment and interaction; home helps often dont even have enough time to travel from one individual they help to the next; and so on…

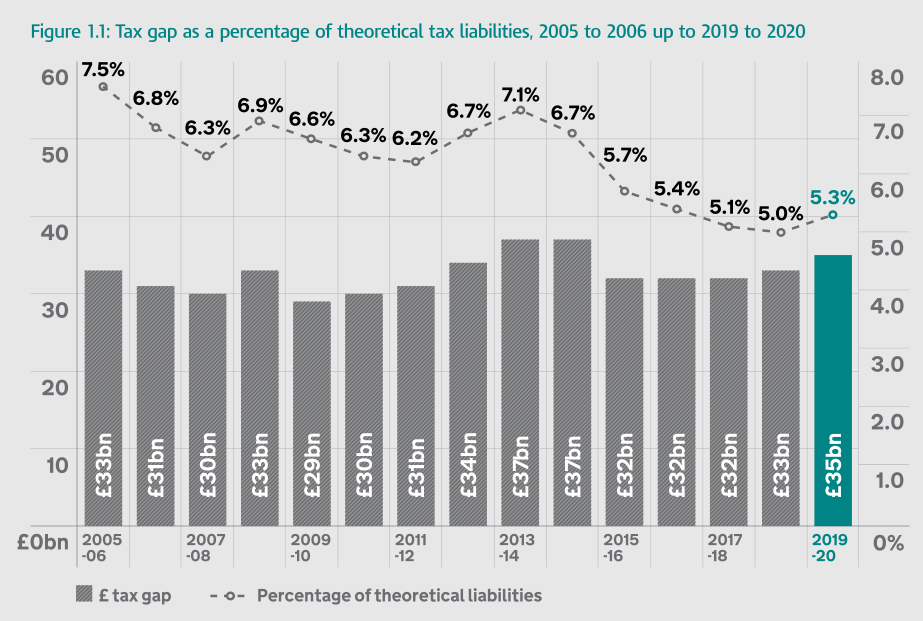

The time for patience to unravel complexity in the lives of people in relation to institutions and administrations has become over ruled by a society which has become financialised before anything else. Cash is repeatedly emphasised over values with ‘but’ statements eerily similar to creepy justification statements along the lines of ‘I am not racist but…’, ‘I am not sexist but…’, ‘I am not homophobic but…’. Whilst the government is failing to collect tax from large corporations to the tune of approximately £66 billion over two years, it is pitting charities and third sectors organisations against each other to deliver cheaper services.

The corrected UK tax gap is estimated to be 5.2% of total theoretical tax liabilities (£34.8 billion) in 2019 to 2020 (0.1 percentage points or £0.6 billion lower than previously published) and 4.9% (£32.2 billion) in 2018 to 2019 (0.1 percentage points or £0.4 billion lower than previously published).

As Philip Alston, probably the most cited Human Rights scholar in the world puts it, “the advice I got clearly in the UK was don’t mention human rights. In other words, there’s been such a big campaign against it, such a backlash [19 min 58 sec]….the theme that I’ve always pushed which is that poverty is a political choice.

Poverty could be eliminated in virtually every country if the political elite actually wanted to do that, but they don’t, they consciously don’t. They want the money for themselves. And so looking at the US and the UK where you’ve got very wealthy economies, they had lots of choices but they still opt to have 15% or whatever of their population living in poverty so I thought it was very important to convey that message and document the linkage [23 min 28 sec]”.

(Transcript excerpt from the video ‘Do Human Rights Investigations Matter ? The Case of the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty’, October 16, 2019 at NYU School of Law with Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law, Margaret Satterthwaite Professor of Clinical Law, and César Rodríguez-Garavito, Founding Director of Program on Global Justice and Human Rights – [19 min 58 sec and 23 min 28 sec])

Do Human Rights Investigations Matter ? The Case of the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty’, October 16, 2019 at NYU School of Law with Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law, Margaret Satterthwaite Professor of Clinical Law, and César Rodríguez-Garavito, Founding Director of Program on Global Justice and Human Rights

As people involved in giving support have their time and income squeezed, they are put under pressure to euphemistically become ‘more efficient’ pairing down what they do for the people they support and how they deliver that support. Hold in mind that these are people who are having to make ends meet themselves, often with loved ones and children to care for, pets to feed, mortgages, debts, and a non-professional life to lead.

The result is that patience and active listening beyond the allocated time limit gets replaced with decisions of convenience. Just like say an elderly relation or a young child starts to get decisions made for them for the sake of convenience (i.e. children strapped into buggies as it is quicker to wheel the child around in constraints rather than let them develop skills and physiology walking; doing something quickly for an elderly relative rather than teaching them how to do it themselves, etc), decisions start to be made for the people they are contracted to support for “efficiency’s” convenience.

For the sake of convenience complex issues are put to the back of the pile; even straight forward ones which seem menial start getting decided – what would you like to eat ? how are you today ? tell me about what is on your mind ? All this is a part of emptying someone’s world and rendering them of agency.

The person becomes infantilised when it strikes the support worker or official that they dont have time to involve the individual by getting them to articulate their experience or explain how the system is broken and that it does not make sense or that the organisational management are manoeuvring people into acquiescing positions to suit top down policy. Stock answers start to get fed into the bureaucratic apparatus that governs the opportunities and futures of the person they are acting on behalf of. The good becomes the enemy of the perfect as essential needs are met under huge work loads which often cause stress related illness in the frontline worker whom is often aware of the skullduggery, the fecklessness, the nonsensical nature and the plain chaos.

Add into this that the individual working in the professional role will priortise their child, feeding their pet, watering their plants, clocking off to meet a friend – all the things which are a part of a healthy life, or else they will end up burning out and not be able to function in their role. Compassion fatigue is often accompanied by secondary trauma, and burn out. In a professional setting where the agent is seeing multiple needs and multiple disadvantages on a daily basis alert fatigue can lead to professionals over-riding their natural empathic and diligent responses.

On top of this people at the bottom of the support-need juncture must deal with, negotiate and/or absorb all the forms of maladministration (which groups of pressured human beings inevitably manifest) in their attempt to get multiple agencies and organisational structures (1) to work, and (2) to work together. This goes some way to starting to get a better picture of what people are faced with at the bottom of a corporate-institutional society like the UK. All the malfunctions of the administrative and governance systems are externalised onto the client groups who often have no choice but to attempt to get support via these.

This is especially so in the tautological neo-liberal meme quasi philosophies of the ‘entrepreneur of the self’ which disguise malfeasence as user error, user incapability, frank confabulation and free rider behaviour. Below is an excerpt from Gerald Caiden’s work in administrative reform detailing obstacles which a principal-client (and an organisation) must face:

“I have found in my empirical research into administrative corruption that often public administrators are victims of political corruption and valiantly try to preserve their personal integrity. I have also found that though bureaucratic corruption manifests itself in public maladministration, by no means can the whole gamut of public maladministration “from simple clerical errors to oppression” including “injustice, failure to carry out legislative intent, unreasonable delay, administrative error, abuse of discretion, lack of courtesy, clerical error, oppression, oversight, negligence, inadequate investigation, unfair policy, partiality, failure to communicate, rudeness, maladministration, unfairness, unreasonableness, arbitrariness, arrogance, inefficiency, violation of law or regulation, abuse of authority, discrimination, errors, mistakes, carelessness, disagreement with discretionary decisions, improper motivation, irrelevant considerations, inadequate or obscure explanation, and all other acts that are frequently inflicted upon the governed by those who govern intentionally or unintentionally” be attributed to bureaucratic corruption. They are more the fault of thoughtlessness, accident, inefficiency, expediency, incompetence, stupidity, indifference, ignorance, self-deception, and self preservation.“

Caiden, G. E (1981) Public Maladministration and Bureaucratic Corruption, Hong Kong Journal of Public Administration, 3:1, 56-71

People die deaths of convenience every day; people are despairing

Local Knowledge and Building Dialogue

The expert-layperson binary teleology (Paolo Freire describes this as the banking model of education) is unhelpful in promoting a transmissive dynamic because it is at the expense of dialogical processes which are vital to tapping into an expanded understanding of complex issues. Only through a communitive process – one which is generative of community – may we examine and compare situational knowledge (expert knowledge is a subset). This requires respect, trust and a social agora [26].

Local knowledge serves as a primary resource for intercultural inquiries into culturally loaded expressions of locally situated social issues such as respect, responsibility, work and welfare. Local knowledge signals the perspectival and partial nature of knowing. An understanding of situational knowledge is a useful juxtaposition to institutional knowledge, and this reveals the necessity for local knowledge in any inquiry [26].

Concern for local knowledge in public discourse is neither new nor unique. In 1989 Beverly Sauer published her analysis of a coal mine disaster in December of 1981. Prior to the accident, the wives of miners knew something was amiss at the time. How did they know? From doing their own science: observing for instance, “the amount of rock dust in their wash cycles” [26].

But they had no public forum to take their insights to whilst their husbands were still alive, and their experiential knowledge lacked evidentiary status at the hearings following the disaster. Sauer interprets the disjuncture this way: “the conventions of public discourse privilege the rational objective (male) voice and silence human suffering…. the notion of expertise excludes the women’s experiential knowledge” [26].

Dorothy Smith instructs us to “begin from the actualities of people’s lives” if we want to understand what is happening to them. Smith is one of the feminist scholars for whom women’s experience remains of key methodological importance, even as it has become contentious in post modern/post structural circles.

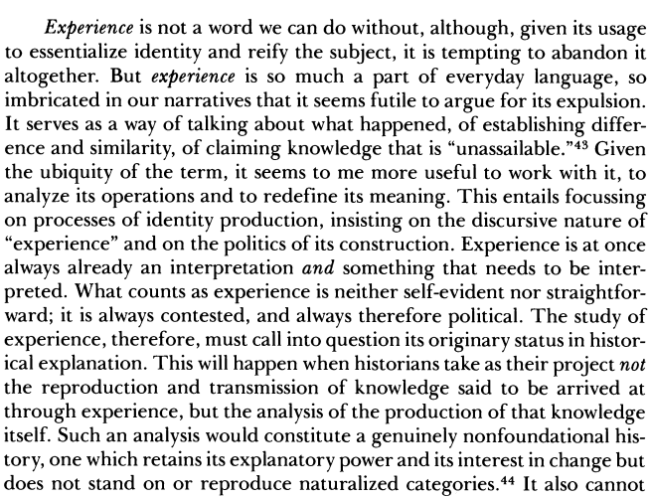

Joan W. Scott states “Experience is at once always already an interpretation and something that needs to be interpreted. What counts as experience is neither self-evident nor straightforward; it is always contested, and always therefore political. The study of experience, therefore, must call into question its originary status in historical explanation. This will happen when historians take as their project not the reproduction and transmission of knowledge said to be arrived at through experience, but the analysis of the production of that knowledge itself” [46].

(Excerpt from Scott, J. 1991, ‘The Evidence of Experience’ Critical Inquiry, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Summer, 1991), pp. 773-797, The University of Chicago Press)

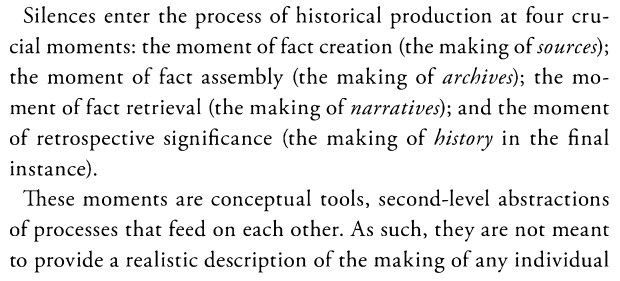

Here it is worth again mentioning Trouillot’s thesis in his book ‘Silencing the Past; Power and the Production of History’ where he establishes that in the creation of every fact, there is the creation of a silence. It is these silences that we are particularly interested in [66]. Another way of framing it is by asking what is missing from the discourse ?

(Excerpt from Michel-Rolph Trouillot, ‘Power and the Production of History’, Beacon Press books, Copyright 1995, ISBN 978-0-8070-4311-0, Page 26)

Existential Phenomenology in psychology builds an understanding of the experience of the human being from the consciousness and standpoint of the individual who is having the experience. In this way it shares strong resonances with the methodological starting point of Institutional Ethnography. McCall suggests that “To ignore the phenomena of conscious life just as they are given in experience is to abnegate the ultimate source of all knowledge in favour of physicalistic dogma [56]

The starting point is from the concrete description of the experience of the given subject who is a co-researcher in the study. It is a process in which the interpretation of their experience is accorded with the co-researcher’s understanding rather than projecting abstract explanations onto the experience of the subject without following the explicit meaning they have given it [63].

Von Eckartsberg puts forward: “We go first from unarticulated living (experiaction) to a protocol or account. We create a ‘life-text’ that renders the experiaction in narrative language, as story. This process generates our data. Second, we move from the protocol to explication and interpretation. Finally, we engage in the process of the communication of findings” [57].

(Excerpt from Von Eckartsberg, R, 1998, Existential Phenomenological Research; Page 21, Phenomenological Inquiry in Psychology: Existential and Transpersonal Dimensions, edited by Ron Valle, ISBN: 0306455439)

Key in this process is the attempt to grasp the whole meaning of the experience – the Gestalt – rather than dissecting experience into impotent parts without understanding its contextualizing setting. It is this contextualizing network which reveals the rich structure of meaning and the sense of the whole experience [63].

If we separate a given experience into abstracted parts we remove each element from its corroborating situation in the context which attests to the authenticity of the ideas contained therein. The greater the distance between the experience and the abstraction, (i.e. the context and its disembodied elements) the further we place ourselves from the coordinating apparatus of the reality. This places the subjective in a special position; one of immediacy, proximity, and one which supplys the conditions for falsification of ideas [63].

In the research/co-research setting, if a given experience is divided into parts and separated from the originator of that experience through language different from that which the person who lives that experience uses, then the discussion of the abstract concepts lose sensible relevance for that person; meaning, sense and relevance are orphaned, marooned, and isolated through a process which enables misidentification [63].

The researcher is cut off from the reality encounter-able specifically through the co-researcher via a process of linguistic metamorphosis. This metamorphosis of information through codification renders knowledge unrecognisable to its origins and prone to deformation without the checks of the original observer (subject/co-researcher) or reality [63]. We cannot grasp a sense of the whole of a given experience by separating the categorical parts from the general context in which every part is based and contributes to.

Each part is entangled and a living element of the identity and function of the other parts. If we are to base our researches solely on such a specialisation of extraction then we run into problems such as making artificial explanations about experiences. This is due to the fact that the researcher is diminished to a position where they are forced to approach the parts from our own alien perspective which is divorced from the sense of the complete experience of the person who lives it [63].

Sokolowski suggests that a whole can be described as a ‘concretum’ – something which exists as a specific individual that can be experienced and approached in a concrete way. There are ‘parts’ which he calls ‘abstractum’ that cannot exist independently and present themselves apart from the whole to which they belong; although we can think about these parts as individuals in their context.

When we think in this way, parts are not concrete things but only abstract objects [63] which gain their meaningful identities from, and through, their relationship with others. Just as a word plucked from a sentence becomes a fraction which bears little or no resemblence to the meaningful living language of its conversational context, so does a ‘fact’ rendered and dressed as a ‘key performance indicator’or outcome in language alien to its origin.

References

[26] Elenore Long, ‘Rhetorical Techne, Local Knowledge and Challenges’; ‘Rhetorics, Literacies, and Narratives of Sustainability’, Peter N. Goggin (Editor); Routledge (June 8 2009) Publication Date: June 8 2009; ISBN-10: 0415800412, Page 13

[46] Scott, J. 1991, ‘The Evidence of Experience’ Critical Inquiry, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Summer, 1991), pp. 773-797, The University of Chicago Press, Accessed Online 20/06/2015:

[56] McCall, R, 1983, Phenomenological Psychology, Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-09414-6, Page 57

[57] Von Eckartsberg, R, 1998, Existential Phenomenological Research; Page 21, Phenomenological Inquiry in Psychology: Existential and Transpersonal Dimensions, edited by Ron Valle, ISBN: 0306455439

[63] Introduction to Giorgi’s Existential Phenomenological Research Method; Alberto De Castro; Psicologia desde el Caribe Universidad del Norte; volume 11; Pages 45 – 56

[66] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, ‘Power and the Production of History’, Beacon Press books, Copyright 1995, ISBN 978-0-8070-4311-0, Page 26