Doctor Thomas Barnardo and the Ragged Schools

This is a conversation with Erica Davies, Director of the Ragged School Museum in Mile End, London. Erica shares deep insights into the Ragged School free education movement and the efforts of Doctor Thomas Barnardo. The Ragged School Museum is a unique place of learning about the Ragged School movement and is the last existing intact school of Dr Barnardo’s, famous champion of free education and welfare. It continues to offer an important cultural space for learning and communities in the locale.

Many know the high street charity Barnardo’s founded by Thomas John Barnardo in 1866, to care for vulnerable children. Thomas Barnardo was an integral part of the Ragged Schools movement having founded several Ragged Schools himself to nurture and support children who otherwise would not have received an education or who were living in chronic and dire poverty.

Seen within the context of the time Barnardo was an innovative and inspired philanthropist who forged systems of social support where they were most needed. Born in 1845 he grew up in Dublin, Ireland, with three other siblings. He was the son of fur trader John Michaelis Barnardo and Abigail Barnardo who was a member of a non-conformist, non-denominational Christian movement called the Plymouth Brethren.

In his adult life Thomas Barnardo had a revelation about his youthful selfishness writing in memoirs he felt that everything should belong to him. This gave way to him dedicating his life to the helping of the poor and making social provision for the needs of people. In 1866 he moved to London with the interest of becoming a missionary. This was 27 years after the death of John Pounds, the famous ‘Crippled Cobber of Portsmouth’ who long before had taken it on himself to provide a place where destitute children were welcome, some provision of food and the sharing of knowledge.

It was in Hope Place in the East End of London that Thomas Barnardo would start a ‘ragged school’ in 1868. Now the site of the Ragged School Museum, it would support and help an estimated 30,000 children who were without means. At the time cholera and illness was rife, working conditions for the poor were terrible being without any regulation, and the Irish peoples (and others) were subject to frank discrimination by authorities.

The kind of education which Barnardo developed in his Ragged Schools was often practically based with the aim of opening up work opportunities for children when as they grew. There was a focus on reading, writing and arithmetic paralleled with the provision of clothing, food and safe board. It was a time which followed huge displacement of populations from ancestral lands by enclosure and bouts of famine. This resulted in a large amount of emigration which followed in the tailwinds of the kind of shameless colonial expansion of the British Empire.

Barnardo arranged various schemes for children to find placement in colonies abroad with the arrangements where the children would be cared for in exchange for their endentured labour for a period. Whilst this is controversial today, in the time it provided opportunities for new lives for many who were suffering extreme poverty and exploitation. Retrospectively this would be problematic due to the hard logistical task of keeping vigil over the welfare of the children.

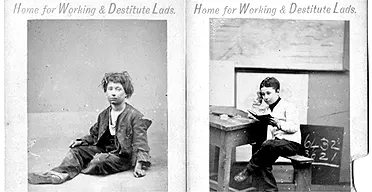

Barnardo wrote and printed various magazines and journals promoting the cause of welfare, education and schooling which are now held in trust by Barnardo’s charity. As a social reformer he used the stories of children, their hardships and their apparent successes to garner more support for a society which sought to banish poverty. Not without controversy, he was accused of taking children from their homes without permission; he argued this behaviour as ‘philanthropic abduction’ and believed that the ends justified the means.

His use of children to illustrate and promote the cause of poverty relief has been criticised as he aggressively campaigned on moral issues falsifying the kind of ‘before and after’ images which would be used to reach the public. He opened various homes in attempts to remove children from the pearls of industrial pollution and to guard them against child prostitution. By the time of his death in 1905 he had established 122 homes and ragged schools which cared for nearly 60,000 children.