Cult Behaviours: Devaluing the Outsider – Reviewing Prof Arthur J. Deikman’s Work

This is the third part of a review and digest of the work of Professor Arthur Deikman who published on cult behaviours examining how they manifest in every day circumstances. He likened the natural pull in everyone towards cult behaviour to the comfort of being a passenger of a car and being driven along without having to think about where the journey is going or how they are getting there.

As a professor of psychology his work examines the internal processes involved in the reproduction of situations that reinforce the non-critical mindless behaviours which result in so many problems. In his book – The Wrong Way Home; Uncovering the Patterns of Cult Behavior in American Society – he discusses in detail the alluring realities which can affect any individual to bond to a group situation that results in ethical travesties warning readers not to think that they are above such influences as they seem to be universal. The book was not just an examination of American Society but society more generally; it just so happens that he was talking specifically to an American audience and that Deikman worked in the USA.

This third instalment of the digest of Deikman’s book which focuses on the third of four characteristics of behaviour which he identifies as embodying the cult. He introduces the reader to the position that whilst his work has taken him to examine the more extreme examples of cult behaviour, such as Wako, there is warranted concern to understand the principles more widely in order that society can be more healthy. The book is structured to discuss the following four attributes:

In this digest of Deikman’s work I have included some of the source references to assist the reader engaging more deeply with the subject. His efforts as an educator, psychologist and social commentator were to prompt us as readers and learners to examine social arrangements in our own lives so that – with a raised level of consciousness – we may counteract some of the group think and ingroup/outgroup tendencies which are inevitable in our institutions, work places, media, social networks, public organisations, family spaces and communities.

Devaluing the Outsider

The security of a cult is bound up with the idea of being special, better than those outside the group. Indeed, outsiders are likely to be seen as threatening since they do not share the cult’s belief in the leader and in the special entitlement of its members. This threat is met by devaluing the non-believers. In part, this devaluation is an expression of the child’s wish that his or her parents be the most powerful, that they know everything and can obtain for their children good things which others do not have. Furthermore, feeling blessed and favored confers a sense of protection, calming anxieties about the world outside.

Devaluing the outsider is probably the most common cult-like behavior in everyday society, where it takes the form of regarding one’s opponents as if they were a homogeneous group with only negative traits. Bad motives are attributed to the other, but not to oneself. This devaluation is usually done by designating the adversary as, for example, “stupid,” “rigid,” “lazy,” “reactionary,” “bleeding heart,” “cold.” When one devalues another no real proof is offered. There is seldom any inquiry into the actual statements and actions of members of the “bad” group, or any serious consideration of the adversary’s point of view and its possible validity, and critical analysis of one’s own “good” view, discriminating between assumptions and facts, rarely takes place.

Examples of this everyday cult behavior can be found on radio talk shows. One major program I have encountered has a host who is perpetually exclaiming at the stupidity of whatever political or bureaucratic figure is the target for the day. He and the caller-in indulge in a festival of indignation and self-congratulation, shaking their collective heads over the “ridiculous” actions that have so astonished them, seldom seeking to understand how the action under attack might be reasonable from a different point of view or even being genuinely curious about it. Instead, the host and the caller engage in cult behavior.

By designating someone else as bad or stupid, they are reassured that they themselves are good, their views commendable. Perhaps the most important thing to understand about devaluing the outsider is that it is a necessary preliminary to harming others, to doing violence. Whether the conflict is between nations or individuals, the attacker devalues the victim prior to the violent act.

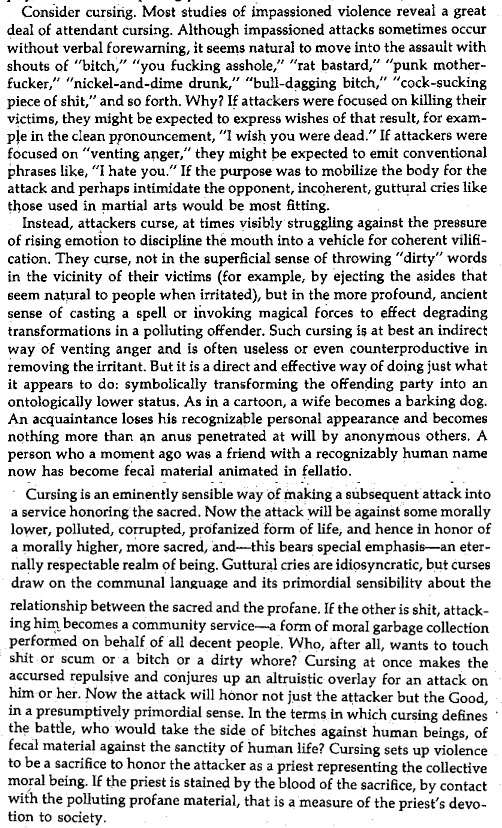

Sociologist Jack Katz studied street gangs and juvenile delinquents and noted the special function of cursing in propelling an attack. Cursing … is a direct and effective way of doing just what it appears to do: symbolically transforming the offending party into an ontologically lower status … If the other is a shit, attacking him becomes a community service—a form of moral garbage collection performed on behalf of all decent people . . . Cursing at once makes the accursed repulsive and conjures up an altruistic overlay for an attack on him or her. [1]

Jack Katz, Seductions of Crime: Moral and Sensual Attractions in Doing Evil (new York: Basic Books, 1988), pp. 36, 37

The person you devalue becomes easier to kill. But when you look at him (or her), be sure you do not see who he (or she) really is, for if you do, you cannot believe he (or she) is inferior to you. A man who had been a medical corpsman in Vietnam remembers the time when he was asked to guard an old Viet Cong. His prisoner looked right into his eyes, and the corpsman looked back. Then the old man was dragged to death behind a truck.

“I will never forget the man’s face, and I will never forget his eyes, and I will never forget holding the rifle at his face . . . I’ll never forget how old he was. There was something about the internal solidity of this human being that I will never forget . . . Something went on that changed my life.” [2]

Quoted in Al Santoli, Everything We Had (New York: Random House, 1981), p. 70

Devaluation relies heavily on projection, “a defense mechanism, operating unconsciously, in which what is emotionally unacceptable in the self is unconsciously rejected and attributed (projected) to others.” [3]

Reference 3

The American Psychiatric Association’s Psychiatric Glossary, ed. A. Werner et al. (Washington, D. C.: American Psychiatric Press, 1984), P. 110

Projection occurs when we attribute to others those aspects of ourselves that we wish to deny. By identifying the bad impulse or trait as being outside ourselves, we can feel more secure. Thus, projection offers protection from the anxiety of being bad and the punishment of being abandoned. In addition, by making other people bad in our own mind, we can legitimize behavior toward them that would otherwise be morally unacceptable, even to the point of sanctioning cruel and vicious actions.

I saw a vivid demonstration of projection at the conclusion of a five-day group relations conference when I joined a small group that was discussing what had been learned. Opposite me was a stocky, muscular young man with a hostile demeanor. I felt that he would physically attack me if I gave him the slightest excuse. I was afraid of him. My feelings were similar to what I had felt toward school bullies when I was growing up. Because during the conference we had dealt with projection, I tried questioning myself to see if I had any aggressive impulses toward the man whom I was afraid of. Immediately, I became aware of a desire to attack, to punch him to the ground.

The violence in me was unmistakable. I looked again at the young man and could not believe the transformation that had taken place. He now appeared mild, nonthreatening, a perfectly nice person. This reversal of perception had happened in that instant of recognition of my own hostile feelings. The experience was vivid, probably because the conference had been designed to intensify projective defenses, but I am sure that similar distortions of perception take place under more normal conditions and that these perceptions can also be reversed.

The effect of projection is often a perception of the other person as being fundamentally different, a morally inferior species, undeserving of empathy. Perhaps the most common form of projection is to condemn others without noting good qualities that may lessen our sense of distance between them and us. In fact, noting an enemy’s less admirable similarities to us can provoke strong feelings. Many people were distressed when Hannah Arendt’s study of Adolph Eichmann, the Nazi war criminal, led her to conclude that he was not diabolical, but banal, a poor thinker, common. [4]

Although the research of Stanley Milgram [5] and Philip Zimbardo [6] suggests strongly that the potential for cruelty and the carrying out of heinous orders is common to all human beings, it is hard for us to acknowledge that we may be less unlike the Nazis than we would wish. Projection protects us all from what we fear.

Reference 5

Stanley Milgram, Obedience of Authority (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), Introduction

Supplementary video:

Footage of the Milgram Experiment

Reference 6:

Philip Zimbardo, et al., “The Psychology of Imprisonment: Privation, Power and Pathology,” in Doing Unto Others; Explorations in Social Behaviour, ed. Z. Rubin (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1974)

Supplementary video

Zimbardo prison experiment (shortened clip)

The more authoritarian the human social system, the more likely a separatist world view will arise because any anger or resentment stimulated in the follower by his or her submission to the leader requires displacement onto other persons—the outsider, the infidel, the non-believer. Feelings of rebellion toward the leader, which are defined by the group as evil, make the cult member anxious, even ready to believe in satanic possession, an apt metaphor to describe the sensation of being invaded by unwanted feelings and images. Projection and a division of humanity into the saved and the damned are called into play with increasing intensity. As a result, the more rigid the system the more powerful is the belief in the Devil or Evil—and the more violent the feelings toward the outsider.

Because projection requires the establishment of separation, of discontinuity, of fundamental differences, the person or group onto whom the badness is projected must be a “not-me”; otherwise one’s condemnation would rebound onto oneself. For this reason we project most often onto other nations, other racial and religious groups, opposing political parties, and economic and social classes different from our own.

However, projection may also be used in ordinary social relationships when the need to feel superior rather than inferior arises often. Thus, we increase our moral security by seeing others as evil, stupid, backward, or arrogant. When we do this we create and maintain cult consciousness in a fashion similar to the fanatic who perceives outsiders as damned, degenerate, and suitable for killing. When average, non-fanatic citizens devalue others they rarely murder them as a consequence, but they may well acquiesce in a political order that does.

Upon reflection you can probably identify your own focus of Projection, your “not-me”: Republicans, Democrats, rich, poor, black, white, Christian, Jew, Muslim, Northerner, Southerner, dove, hawk, old, young, men, women. Projection is so much a part of our thinking we seldom notice it, except when someone else does it. One of the symptoms of projection is an attitude of righteousness coloring persons’ statements of their beliefs and views of others. As we have seen, through projection we reassure ourselves that we are good (as in the child’s world) by pointing out that someone else is bad. The covert “I am good” is signaled by self-righteousness, which requires the devaluation of someone else.

Self-righteousness is the dominant attitude of cult members, although it may be masked by false humility and public confessions of unworthiness. Righteousness has a special vocabulary that establishes two species of human beings. Of course, the vocabulary of righteousness is seldom as stark outside of the religious or political arenas, but may include such terms as “unscientific,” “neurotic,” and “infantile,” as opposed to “mature,” “realistic,” and “rigorous.” Being thus negatively labeled amounts to rejection. Understandably, we are usually very sensitive to our own group’s criteria for inclusion or casting-out.

Righteousness protects against self-doubt and at the same time provides a rationale for actions that would otherwise place us in the bad category. By intensifying righteousness a person can retain the feeling of being good while performing shameful acts; cruelty is justified, may even become a duty. There is no cruelty like the cruelty of the righteous.

Righteousness can be seen in many one would assume were not susceptible to cult thinking, scientists, for example. Proponents of theories which challenge accepted views are sometimes vilified with a zeal that combines righteousness and arrogance. One example from the history of medicine is that of the nineteenth-century Hungarian physician, I. P. Semmelweis.

Semmelweis came to the conclusion that the high incidence of puerperal fever (which killed many in childbirth) among women who delivered their babies in hospitals was due to contamination by attending physicians who, at that time, routinely went from the autopsy room to the delivery room without cleansing their hands. His theory and his recommendation that physicians wash was received with such ridicule and followed by such professional persecution that he eventually went mad.

Supplementary video

The surprising history of hand-washing – BBC REEL

A more current example of the effects of scientific righteousness and the arrogance it fosters is provided by the development of the atomic bomb. Although the research was initially justified by the fear that the Nazis would attain the bomb first, the work did not stop when that concern was eliminated by the Allied invasion of Europe.

Only one scientist left the enterprise; the rest continued what they had begun. Recently we have begun to recognize the responsibility borne by scientists for the nuclear threat that now hangs over the world. Following a reunion at Los Alamos of many who had worked on the atomic bomb, Isador Rabi, the Nobel prize-winning physicist, was asked if he thought it likely that there would ever again be such a collection of scientists working with the same dedication and idealism. Rabi’s response was unhesitating. “I hope not,’ he said. ‘We had no doubts about what we were doing.'” [9]

Reference 9:

Quoted in Harper’s, December 1983, p. 55

Religions are particularly prone to devaluing outsiders because to accord outsiders equal status is to give respectability to their different versions of God and lessen the certainty of faith. Doubt may arise. Even if the outsider is not specifically devalued, scorned, or hated, theistic religions tend to reward followers with special status: the Jews are the chosen, good Christians are saved from hell, true Muslims go to paradise. The non-believer, in many instances, is a damned infidel.

But it is not the search for truth which leads a person to massacre or torture, to ostracize and expel, to scorn and to hate; nor is it a search for bliss or other, spiritual, states. In subtle or not so subtle ways, most religions utilize devaluation despite their best intentions. If you think not, listen closely to the next sermon you hear.

The consequences for the outsider can be significant indeed. Because religions deal in absolutes, the devaluation of the outsider can be absolute also, justifying behavior toward the innocent and helpless which the religion’s founder would have condemned and which by any humane standard is barbaric. The Crusades were often a license for the murder, rape, and devastation of “infidel” peoples, those with different religious beliefs. Within Christianity, the religious passions of Catholics and Protestants fueled the Thirty Years’ War which almost totally destroyed Germany in the seventeenth century. More recently, Hindus and Moslems created the nightmare of fighting in Bangladesh, featuring indiscriminate slaughter and numerous examples of gang rape all under the banner of their respective religions.

Less violent forms of devaluation are almost universal. Members of most religions can be hostile, or at best uneasy, at the prospect of their children marrying outside the faith, even outside the particular sect to which they belong. When a son or daughter of Orthodox Jewish parents marries a non-Jew the parents sometimes conduct services for the dead, psychologically burying their errant child. Until 1984, a non-Catholic who married a Catholic had to sign a promise to raise their children as Catholics if the couple were to be married by a priest.

This exclusivity is not hard to understand. All groups exist by virtue of membership boundaries; the more lax those boundaries the weaker is group cohesion and group strength. As a consequence, group boundaries are defended vigorously. Since intermarriage poses the greatest danger to religious boundaries, it is punished in overt or subtle ways; natural family ties may be subordinated to the larger religious group. As in extreme cults, family bonds may be seen as secondary to preserving the exclusiveness of the religion, the superior status of the followers and the inferior status of those outside.

Fundamentalist religions, in particular, tend to devalue the outsider to preserve the certainty of their scriptures and their leader’s connection with God. In recent years, a conservative American Christian fundamentalism has experienced a resurgence and now claims many millions of members. Since many of these fundamentalists are also members of mainline churches, it is hard to know exactly how large the group is, but informed estimates suggest they number well over twenty million. [10]

Over recent years this movement has established powerful radio and television broadcasting networks, made extensive use of direct mail for fundraising and recruitment, and sponsored a vast increase in fundamentalist parochial schools where authoritarian, separatist, sectarian views are taught. Many teach that only “true” Christians—those “born again”—will be saved; the rest will go to hell. The Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart scandals did not appreciably change the popularity of these religious movements.

As evil and an assortment of devils came to dominate the consciousness of Alex Monroe and the Life Force group [the case study Prof Deikman uses to illustrate the characteristics of cult thinking], Satan and evil spirits dominate the world of many fundamentalist religious sects, whether Christian, Islamic or of any other denomination.

Even in psychiatry, the readiness to classify as alien those who do not belong to one’s group may result in a devaluation similar in kind to that which what takes place in cults. This is not usually identified as cult behavior because there is no specific cult of psychiatry nor, with few exceptions, are there hospital cult leaders. Nevertheless, the use of projection may occur and the result is a distortion of reality and adverse effects on the “outsider.”

To identify with a person who is crying because his or her spouse has left is not difficult for a psychiatrist. To identify with one who is screaming, smearing feces, psychotically suicidal, assaultive, or self-mutilating is quite another matter. Although the impulses represented by extreme, psychotic behaviors are present to some degree in every person, including the psychiatrist, they constitute precisely those impulses most strenuously suppressed and rigidly controlled.

The deepest infantile wishes are represented in the overt and seemingly guilt-free regression of psychotic patients, who abandon the status of the adult for the humiliation and gratifications of the infant. Such passive, infantile wishes are more taboo in our culture than neurotic sexual behavior. I believe the difference in treatment usually given people exhibiting psychotic symptoms versus the treatment provided for those whose symptoms are closer to the therapist’s cannot be understood only as the result of a belief in biochemical causation of psychosis. Rather, I think we need to recognize a therapist’s unconscious wish to see as alien the person whose behavior represents the bad qualities that threaten rejection in one’s own group.

I believe this separation and devaluation lies behind the striking difference one can observe between the way psychiatric treatment is conducted in outpatient departments and the way treatment is provided to inpatients, even in university-affiliated hospitals. Inpatients receive drug therapy with neuroleptic drugs such as Mellaril or Haldol, plus a smattering of psychological treatment under the euphemism of supportive therapy.

If psychiatric residents are being trained on the ward, patients may also have individual psychotherapy, but neither patient nor novice therapist expect it to be effective (and under these conditions psychotherapy seldom is). In contrast, most outpatients receive analytically oriented psychotherapy, psychological treatment based on psychodynamic principles, unless the outpatient is a transfer from the hospital; in that case, therapy is often focused on medication, dealing with drug side-effects, and managing the living situation. Such patients are often seen for less than the fifty- minute hour usual for outpatient therapy.

The division of patients into two classes, the psychotherapy outpatient group and the medication-inpatient group, seldom receives critical comment, nor does the fact that inpatient procedures frequently violate the psychodynamic principles assumed to be operative for outpatients. For example, at one medical school where I taught, nursing students were assigned young, first-time schizophrenic patients with whom they were expected to establish rapport and a therapeutic relationship. After six weeks the nursing students left for other duties; psychiatric residents stayed for six months, then they too left. These practices were standard despite the knowledge that the loss of a parent, spouse, or lover was often the precipitating event for the psychosis from which the patient was suffering. The departures of the nursing students and the residents could only intensify feelings of loss. One had to conclude that psychodynamic considerations received short shrift on the hospital ward.

Another indicator of the separate status of inpatients at this hospital was that although medication was supposed to be individually prescribed, almost everyone admitted to the unit with a diagnosis of schizophrenia arrived from the emergency room heavily dosed with neuroleptic drugs, and on the ward, the neuroleptics were continued. As a result, no drug-free period of observation and treatment planning occurred. If behavior did not improve, the drug dosage was increased.

When we studied the exact sequence of events that preceded a decision by ward staff to increase a patient’s medication, we found that in almost every case the patient had shifted from inactivity, depression, or apathy to being noisy, “crazy,” threatening, or messy. The possibility that this shift might signify progress in the patient, a beginning attempt to communicate feelings, was not considered. Where exploration, uncovering, and communication were highly valued in outpatient services, in the inpatient world management and suppression of behavior had priority.

The dividing line between neurotic (outpatient) and psychotic (inpatient) problems is not completely clear; it appears to be only if one compares the most healthy neurotic patients and the most psychotic. So many people suffer from intermediate conditions that the diagnosis of “borderline” has had to be employed as a bridging category. Even the diagnosis of schizophrenia encompasses such a wide variety of conditions that numerous sub-types are employed and the diagnostic criteria are non-specific and constantly revised. If one grants that both environmental (psychological) and biochemical factors influence human behavior, the sharp split in psychiatric practice cannot be defended on rational grounds.

The split occurs, I believe, partly because the seriously disturbed patient is devalued as an outsider by the psychiatrist. This became clear when a colleague and I changed a drug-oriented psychiatric ward into an intensive psychological treatment unit, one that focused on the relation between early life experience and the patient’s behavior on the ward. [11] Drugs were not used unless psychological treatment proved ineffective. As a result of this change in orientation, staff paid much more attention to the ward dynamics and the role of both patients and staff in intensifying or diminishing psychotic behavior. There was much to learn.

Reference 11

For further discussion, see Arthur J. Deikman and Lee C. Whitaker, “Humanizing a Psychiatric Ward: Changing from Drugs to Psychotherapy,” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 17, pp. 85-93

One day “Jerry,” a weird-looking adolescent sitting crouched in a wheelchair and diagnosed as paranoid and retarded, was admitted (by mistake) to our ward instead of being shipped off to the state hospital for what I would call warehousing. Jerry seemed like an idiot, would occasionally drool, liked to wheel rapidly around the ward with a crazy look on his face, and replied to questions and orders only in the most halting manner. The nurses were afraid of him, but we had to keep him for a few days until a transfer could be arranged. During this time one of the nurses remarked that she didn’t think Jerry was as retarded as he seemed; she thought he knew what he was doing. So we confronted him, saying, “Jerry, what’s this big act you’ve got, trying to scare everyone? You’re not that crazy, you’re not that dumb.”

A big smile spread slowly over his face and the crazy look went away. We never did send him to the state hospital. He wasn’t an idiot. He was paranoid, but not severely, and much of his behavior related to family dynamics which then became the focus of treatment. Jerry was more like us than different, doing what he thought necessary to meet his needs and protect himself. He had made use of people’s readiness to see him as alien, to devalue him, in order to gain power for himself, the power of frightening others and of being able to hide.

“Juanita,” a very depressed Mexican-Indian woman in late middle age who had almost no formal education and spoke very little English showed us how outsider status can be conveyed by cultural differences as well as by psychiatric symptoms. Juanita gave all the appearance of a backward peasant who could not comprehend much of what was going on around her. We gave her a suitable therapeutic task for someone as limited as she seemed to be—cleaning tables. Before long, Juanita was causing considerable turmoil on the ward, covertly expressing her anger at the staff and other patients. We were forced to recognize that underneath, Juanita was a strategic planner like the rest of us. When we were able to see who Juanita was, we took her off the cleaning job and treated her as a conscious, equal member of the patient group. Her depression decreased and the disturbance on the ward disappeared.

Media owners, editors, and reporters, like other people, are motivated by ideals, not just money or power. Most believe (some passionately) that reporting the society’s imperfections and providing the public with a diversity of views and information is their special function and responsibility, that which gives meaning to their work. I am speaking here of societies which value a free press. The problem is that discharging that responsibility may conflict with support for the status quo. One way in which this dilemma can be solved is by being careful to report that dissent exists while devaluing it at the same time. This can be done covertly, even unconsciously, by means of the selected image.

Most news magazines and newspapers maintain a file of photos of prominent people and it is easy to select one in which a politician or other celebrity looks ridiculous, sinister, or ugly. Additionally, the photo can be juxtaposed with one that flatters whomever the editor wishes to promote. If you look for this device you will see it used frequently, especially at election time. Technically, it is fair, all sides are receiving publicity.

The selected image is used most powerfully by television, which presents, after all, a series of discrete scenes while attempting to convey a reality much larger than what can be framed. What the commentator or editor selects tells a part of the story, not the whole story. The power of the selected image resides in the fact that we respond to news photos and television as if they are showing us objective facts devoid of interpretation. The image seems to validate itself.

Sociologist Todd Gitlin experienced this aspect of the media as a leader of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Later, he analyzed the media’s use of the image and found that news photos operate under a hidden sign marked, “this really happened, see for yourself.” Of course, the choice of this moment of an event as against that, of this person rather than that, of this angle rather than any other; indeed, the selection of this photographed incident to represent a whole complex chain of events and meanings, is a highly ideological procedure. But, by appearing literally to reproduce the event as it really happened, news photos suppress their selective/interpretive/ideological function. They seek a warrant in that ever pre-given, neutral structure, which is beyond question, beyond interpretation: the ‘real world.’ [12]

Reference 12

Todd Gitlin, The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left (Berkeley: university of California Press, 1980), p. 48 (note 22).

Television makes optimum use of this see-for-yourself power. Consequently, in many parts of the world, the nightly news shows probably shape people’s perception of events more vividly and more effectively than any other source of information. Considering this power, it is worth noting that what appears on the ABC, CBS, and NBC nightly newscasts is a selection and interpretation largely created by six people, the executive producers and anchor persons of each of the three networks.

Words also can be used very effectively to devalue opposition. I remember how the media in the early sixties characterized the members of SANE (myself being one of them) who opposed the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. While dutifully reporting our campaign, the media tended to dismiss us as having no significance; one columnist called us “small dogs barking at an express train.” Being consigned to ineffective canine status was a frustrating and depressing experience. The media preferred the image of President Kennedy, who dramatically drank a glass of milk at a convention of dairy farmers to express his disdain for charges by SANE that nuclear testing was contaminating milk products with strontium 90. Fortunately, the media were wrong. After Kennedy eventually signed a treaty banning atmospheric testing, SANE acquired respect.

The same devaluing, followed eventually by acceptance, has taken place with regard to anti-nuclear power activists. The accidents at Three Mile Island and, later, Chernobyl resulted in the anti-nuclear movement being legitimized; groups that had been ridiculed now receive more serious treatment than in the past. However, those who challenge nuclear weapons development by committing civil disobedience at Lawrence Livermore Laboratories or at submarine bases and missile sites are still labeled radical. Their arrest by police is reported, but their critique of weapons policy rarely is.

Reality may be distorted simply by screening out dissenting views without the outright censorship seen in totalitarian countries; reality may be distorted by giving great prominence and validity to the established view while devaluing dissenters and making them marginal. Gay rights activists, anti-nuclear groups, and others outside the establishment evoke clear contemporary examples of devaluation.

Supplementary video

How The Media Stopped Us Caring About the Planet | George Monbiot

The treatment of student dissidents in the mainstream media during the 1960s offers good examples of the use of negative adjectives and selective photos combined with the ignoring or minimizing of the issues raised. As Gitlin pointed out with regard to American politics of the sixties, an official typically was given the voice of calm rationality; dissidents were often portrayed as unreasonable, naïve, impulsive, ridiculous, violent and extreme. Some may have been, to be sure, but those who were not were seldom given a forum.

Most of the time the taken-for-granted code of “objectivity” and “balance” presses reporters to seek out scruffy-looking, chanting, “Viet Cong” flag-waving demonstrators and to counterpose them to reasonable-sounding, fact-brandishing authorities . . . Hotheads carry on, the message connotes, while wiser heads, officials and reporters both, with superb self-control, watch the unenlightened ones make trouble. [13]

Reference 13

Todd Gitlin, The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left (Berkeley: university of California Press, 1980), p.4

Writing about the same era, Daniel Hallin found a similar devaluation in the media, in which protest was equated with violence, authority with competence and order. Cronkite began one report on college antiwar protests by saying, “The Cambodia development set off a new round of antiwar demonstrations on U.S. campuses, and not all of them were peaceful.” The film report, not surprisingly, was about one of the ones that was not peaceful, and dealt mainly with the professionalism shown by the authorities who restored order. ’ [14]

Reference 14

Daniel Hallin, The Uncensored War: The Media and Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 200

In contrast, when the protest occurs in a communist country, American news media are likely to handle it differently. Of course, devaluation also takes place in the American media’s coverage of international affairs. Consider the view of the Soviet Union that was maintained by our mainstream media until very recently.

Princeton University professor Stephen Cohen describes a pattern of media coverage that systematically highlights the negative aspects of the Soviet domestic system while obscuring the positive ones. Soviet crop failures and abuses of political liberties have been the regular focus of American news stories since the early 1970s, but expanded welfare programs and the rising living standard have gone largely unreported . . .

Much American commentary on Soviet affairs employs special political terms that are inherently biased and laden with double standards . . . The United States has a government, security organizations and allies. The Soviet Union, however, has a regime, secret police and satellites. Our leaders are consummate politicians; theirs are wily, cunning or worse. We give the world information and seek influence; they disseminate propaganda and disinformation while seeking expansion and domination. [15]

Reference 15

Stephen Cohen, Sovieticus: American Perceptions and Soviet Realities (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985), pp. 29, 30

There is an implicit devaluation of others in nationalism. I consider myself to be internationally minded, free of jingoism. However, not long ago, curious to hear what other countries were saying about world events, I bought a shortwave radio. As I dialed from one foreign station to another, I was surprised to find that the United States was not the center of the world.

In Brazil, South American affairs and not those of the United States were being discussed; in England, the focus was local politics and reactions to a proposed tunnel to France. The effect was a little eerie; my own country seemed to have disappeared. I knew that nationalism was a pervasive phenomenon, but my own parochialism— revealed by my surprise—had been unrecognized. Devaluation of other nations seen as enemies is a pervasive problem for governments.

Misperception of the enemy (basically a devaluing of the foreigner), seeing its people as less advanced, less principled, less admirable, and more deserving of punishment and harsh treatment than ourselves, has affected international relations throughout history, contributing to conflict and to spirals of increased armaments. The arms race is not a new phenomenon and the view that the enemy must be “dealt with firmly” has had adherents. Political scientist Robert Jervis, in discussing the way misperception takes place in international relations, cites two statesmen of the nineteenth century, whose devaluing statements mirror each other:

[James Polk:] … if Congress faultered [sic] or hesitated in their course, John Bull would immediately become arrogant and more grasping in his demands; & that such had been the history of the British [sic] Nation in all their contests with other Powers for the last two hundred years. [18]

[Lord Palmerston:] A quarrel with the United States is . . . undesirable . . . [but] in dealing with Vulgar minded Bullies, and such unfortunately the people of the United States are, nothing is gained by submission to Insult & wrong; on the contrary the submission to an Outrage only encourages the commission of another and a greater one—such people are always trying how far they can venture to go; and they generally pull up when they find they can go no further without encountering resistance of a formidable Character. [19]

Reference 18

Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 65

Reference 19

Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 61

Polk was ready to see Britain as responding only to “firmness,” meaning force, while Palmerston had the same view of the United States. Each was the outsider to the other and, accordingly, was devalued to maintain the righteousness and purity of the home nation’s position, as in the following (one of countless modern examples of reciprocal devaluation):

[John Foster Dulles:] Khrushchev does not need to be convinced of our good intentions. He knows we are not aggressors and do not threaten the security of the Soviet Union. [20]

[Khrushchev:] It is quite well known that if one tries to appease a bandit by first giving him one’s purse, then one’s coat, and so forth, he is not going to be more charitable because of this, he is not going to stop exercising his banditry. On the contrary, he will become ever more insolent. [21]

Reference 20

Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 68

Reference 21

Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 61

The righteous indignation of contemporary leaders echoes statesmen throughout history who have believed that the armaments of others demonstrate aggressive intentions but did not apply that reasoning to arms build-ups of their own. Estimation of the significance of another country’s military budget is especially vulnerable to this error. Intra-service rivalries and parochial political maneuvering are at least as important in promoting the current arms race as any grand, organized strategy, but neither the USSR nor the United States appear to give these factors much weight in evaluating the armaments decisions of the other side, certainly not as far as public pronouncements are concerned. [22] The psychological problem is that recognizing these internal concerns would soften the distinction between good and evil governments and suggest areas of uncomfortable similarity.

Reference 22

Arnold Kanter, Defense Politics: A Budgetary Perspective (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975)

Devaluing the outsider is made manifest in righteousness, in blindness to the implications of one’s own behavior, in the refusal to acknowledge similar intentions on both sides, in the identification of the other as bad in contrast to oneself as good. All these are hallmarks of cult behavior.

In every person’s life, given a psychologically threatening situation, devaluation can extend to friends with the consequence that slights and insults may be perceived when none are intended. I remember hearing Abraham Maslow, the psychologist who helped create humanistic psychology, as he reminisced about his life and spoke of his sense that his own death was near. Shortly before, he had made a pilgrimage across the United States to visit all the people with whom he had once been friends but had fallen out.

He wanted to understand what had happened. What he learned was sad, ironic, and hopeful at the same time. In each case he and the friend had had an interaction whose meaning was ambiguous; Maslow might have ignored an invitation or the other person might have behaved coldly toward him. Of all the possible explanations that he or his friend considered at the time—he’s worried about his job, he forgot, he is ill, he’s angry at me, he dislikes me—each placed at the top of the list the explanation that which was least flattering to himself. And in every case they were wrong.

I call this the Maslow principle and frequently tell the story to my patients, since the problem comes up so often. Even in daily life, it is often hard to realize that the other person is just like us, to see him or her at eye level. Almost everyone tends to give a negative interpretation to another person’s behavior in ambiguous situations. When we do this, it seems logical; when someone else does it, we find it paranoid and hard to believe.

Governments, composed of people, behave no differently. As Jervis points out, they usually view the actions of other governments as deliberate and give scant consideration to the possibility that confusion, chaos, accidents, and coincidence may be responsible; that the consequences of the other’s actions may have been unintended.

Although stupidity and confusion may be responsible for a particular government action (these factors operate at least as frequently as cunning and deceit), they are seldom given much weight when analyzing the actions of an opposing country. When the German battleship Goeben escaped from a superior British force at the beginning of World War I, the Germans tried to understand why the escape had been possible. “To attribute this coup to a blunder on the part of the British admiral in command seemed so unlikely that Bethmann-Hollweg and the German Chief of the Admiralty were inclined to conclude that Britain was unwilling to strike any ‘heavy blows’ against Germany.” [27] The Germans ended up seriously miscalculating British intentions, with very adverse consequences for Germany.

Reference 27

Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 323

Everyday paranoia can extend to the business world, where the battle is economic; cultural differences may be ignored in favor of explanations assuming craftiness or conspiracy. For example, discussions over the joint production of the Concorde almost broke down and aborted the project when the French preference for Cartesian precision ran up against British preference for cautious empiricism.

Unfortunately [this preference] tends to make the French suspect the British more often of duplicity than of simplicity . . . One British aircraft executive involved [in conversations with the French over the Concorde] was reported as having complained that: “The French always think we’re being Machiavellian, when in fact we’re just muddling through.” [28]

Reference 28

Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 328

Recently we have had a devastating illustration of the price of devaluing the outsider—the failure of our society to respond adequately to the AIDS epidemic. Randy Shilts, in his book And The Band Played On, chronicled the lost opportunities to control the disease, the needless deaths of thousands of people, and the even greater losses to come in future years as a consequence of this neglect. [29]

Reference 29

Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On: People, Politics and the Aids Epidemic (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987)

The reason for our failure is clear. From early on, when its effects first appeared as a high incidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma, AIDS was regarded as a disease of homosexuals. To many in mainstream American society, homosexuals are outsiders, ridiculed, feared and often despised as alien. Because it was homosexuals who were dying, few people outside that group cared. Extreme fundamentalists regarded AIDS as God’s punishment, and others felt it served “them” right.

In contrast, Legionnaires’ disease had evoked an instant, fully mobilized response by health agencies, the government, and the media, even though it was a less deadly, less horrible killer than AIDS. In the first twelve months of the AIDS epidemic, the Center for Disease Control had spent $1 million compared to $9 million spent on Legionnaires’ disease.

Newspapers paid little notice to the growing AIDS disaster until intravenous drug users were afflicted. Drug addicts, too, are outcasts, but they are heterosexual. The first coverage of the epidemic by the Wall Street Journal came in 1982 under the headline, “New, Often-Fatal Illness in Homosexuals Turns Up in Women, Heterosexual Males.”

Shilts’s chronology of the disease is a chilling portrayal of the effects that devaluing the outsider can have upon the outcast group and, eventually, upon those who cast them out as well. After four years, AIDS cases in the United States totaled 9,000 and of these 4,300 people had died. No massive response by the government or the media had yet taken place.

To appreciate the magnitude of these figures it should be recalled that Legionnaires’ disease had claimed 29 lives, the poisoned Tylenol capsules had caused 7 deaths. Both of these crises elicited mobilization of all the resources the nation could muster and front-page, extensive coverage by the news media.

Not until the middle of the 1980s, when it became clear that AIDS could strike anyone, did the media give AIDS the full treatment and the government follow suit. Unfortunately, by then there were 12,000 cases, 6,000 people had died, and a virus whose latency can run eight years or more was lodged in tens of thousands who would yet fall ill. As of February 1990, reported AIDS cases totaled 121,000, with 72,000 deaths.

Shilts describes how in Washington, Arthur Bennet, an AIDS sufferer, stood in the rain with other protesters and gestured toward the White House, saying, “I think in the beginning of this whole syndrome, that they, over there, and a lot of other people said, ‘Let the faggots die. They’re expendable.’ I wonder if it would have been 1,500 Boy Scouts, what would have been done.” [30]