Human Rights and the Psychiatric Setting

This is an article exploring human rights in relation to the mental health industrial complex which has risen to articulate the way which people are treated in response to their need for support. In this piece of writing I examine human rights discourses in the context of present day Britain and deconstruct some of the ideological narratives we find intersecting in mental health ultimately asking questions about harms and interrelationships.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The intention of this article is an exploration of different configurations of understanding mental health picking up on cascading possibilities which can impact on individuals in negative ways. Making sense of a highly disputed and conflict riven area of thinking and life itself like mental health is one of the great challenges of our time.

For the last twenty years I have researched biochemistry of various living processes becoming interested in the science by studying things like the production of substances in the body by enzymes and what goes wrong when those enzymes stop doing their job. My research focused over the years many times on understanding physiological causes of altered cognition, memory and affect; for example, how changes in the function of the thyroid can result in psychiatric manifestations.

I continue to research and explore the increasing volume of biochemistry related to the nervous system and the brain and practically every other part of us. The availability of knowledge produced from the academic scientific community is very encouraging for the way that with a computer and the internet you can access a library far exceeding any physical library which could be built practically. Anyone can in principle access a significant amount of robustly done peer reviewed materials on say the myelin sheath which insults the nerve.

Whilst it was my first literacy the more I came to think about and research the field of psychiatry, the more I kept on coming across incidences where there were systems effects in bringing about harms which could not be accounted for through biochemistry models. Critical mental health studies is gaining ground because there has been so much evidence accrued for correctives to be suggested to the existing schemes of thought.

When I say systems effects because there are many different systems which have an effect on the state of someone’s wellbeing. This means that we can only get at certain understandings by employing systems thinking to the study of problems. In part by philosophical evolutions like those suggested by Fritof Capra and Gregory Bateson.

There are no easy answers, and in some cases uncomfortable answers, in any particular enquiry into anthropologically loaded cultural perceptions of what mental health is and is not. Taking a position on cultural responses to mental health should be slightly comfortable because there is learning to do and change to be made in responses to that learning. The positions I take in critical mental health studies are not to dismantle medicine but to search for an evolution in the practical understanding of maintaining good cognitive, emotional and physical health which is needed.

Inevitably for anyone who claims an interest in mental health, there is a requirement to understand the sociology associated and to consider how to negotiate human rights issues as they play out in the lives of individuals and communities. Through becoming aware of the work which Tom Todd had been doing in relation to the Scottish Mental Health Law Review and helping coordinate a blog with academics in Australia around challenging corporate medical companies and their influence in medicine in their book ‘The illusion of evidence based medicine‘.

Tom Todd asked me to write an article for the blog on human rights which packs down all the research covered in this article to 800 words. I asked him if I could publish the long version and this is it. It includes annotations such as videos, papers and excerpts from original sources in the gray boxes so that the reader can make a more comprehensive examination of the arguments and sources. The intention here is to produce a study resource that allows readers to develop deeper insights into the issues raised by including the annotations.

Unpacking Human Rights in the British Context

When asked to write on this subject immediately what came to mind was what the worlds most quoted Human Rights scholar, Prof Philip Alstom, said about the UK: “…the advice I got clearly in the UK was don’t mention human rights…” (Alston, 2019).

This is the kind of backdrop we are working in as citizens of Britain, it may be counterintuitive for whom the culture works but there is something wrong in Eden. As Philip Alston continues, “…In other words, there’s been such a big campaign against it, such a backlash [19 minutes 58 seconds]….the theme that I’ve always pushed which is that poverty is a political choice…

…Poverty could be eliminated in virtually every country if the political elite actually wanted to do that, but they don’t, they consciously don’t. They want the money for themselves. And so looking at the US and the UK where you’ve got very wealthy economies, they had lots of choices but they still opt to have 15% or whatever of their population living in poverty so I thought it was very important to convey that message and document the linkage [23 min 28 sec]”.

(Transcript excerpt from the video ‘Do Human Rights Investigations Matter ? The Case of the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty’, October 16, 2019 at NYU School of Law with Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law, Margaret Satterthwaite Professor of Clinical Law, and César Rodríguez-Garavito, Founding Director of Program on Global Justice and Human Rights – [19 min 58 sec to 23 min 28 sec])

Do Human Rights Investigations Matter ? The Case of the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty’, October 16, 2019 at NYU School of Law with Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law, Margaret Satterthwaite Professor of Clinical Law, and César Rodríguez-Garavito, Founding Director of Program on Global Justice and Human Rights

I start this article touching on poverty because I argue in much of my work that poverty is the source of many harms which show up as mental and physical illness. Whilst there are frank and clear forms of poverty in certain parts of Britain, I argue that there are also new forms of poverty which culturally invisible because we collectively have not developed the common language to talk about them; without the words to articulate something people simply cannot discuss them.

We are presented the wealth of Britain as fact and in the shadow of these statements there are silences created. In many ways we are dealing with a brave new world where the anthropological histories have sublimed to new forms with claims they have shed their histories. Let me unpack that statement a little.

I am suggesting that whilst our current epoch states itself as having moved on from heritages of superstition and theocratic thinking of the past for science and enlightenment, those superstitions and forms of thought which were found in earlier times have reinvented themselves using the languages and rituals of modernity.

Poverties which existed as visceral and overt have shed their their old identities in a manner analogous to Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon where the brutalities of the jailer were reinvented by the constant threat of surveillance. Bentham and the perspectives he laid out illustrated the move from prisoners being pilloried (public humiliation and physical abuse) to being “pilloried in the abstract” (made to wear masks and given a sense of being perpetually surveilled).

[page 6, Bentham J. (2011). The Panopticon Writings. Verso]

The prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment” first appeared in the English Bill of Rights in 1689 and likely played a part in the rejection of Bentham’s Panopticon vision for prisons, hospitals, schools, sanatoriums, and asylums. In related ways I suggest that new means of impoverishment have been brought into existence along with the introductions of technology and lives encased in administrative systems, many of which lack transparency and are unaccountable – in part because the law has not evolved.

The way that concepts of seeming abstraction might have bearing in the visible world strikes me as yet to be fully grappled with and is a subtle notion which I am exploring. For example how privacy has a bearing on glucocorticoid (cortisol) stress levels and, in consequence, mental and physical health is impacted scarcely gets mentioned in relation to socio-economically poor communities being constantly surveilled by security cameras when correspondingly more wealthy neighbourhoods are not.

The effects which dysfunctional administrative systems have on health and wellbeing is another example of issues which involve an abstract nature which I suggest can significantly impact on mental and physical health – situations which can evoke the neurochemical cognitive blunting described famously by the work of Martin Seligman and Steven Maier in coining ‘Learned Helplessness‘. But, because the violence is sublimed into a structure where no individual person can be identified as inflicting a physical violence on a person or group, it is taken less seriously or doubted as to exist.

This work is research and writing I am doing as a part of problematising attitudes and approaches to psychological wellbeing, it is necessarily explorative in its nature searching for better perspectives that the ones which are operating today. As a part of Mad Studies it takes critical views as vital means to stimulating unsanitized, disruptive conversations needed to identify avenues of progress and also social justice issues.

As the context I live in and study is Britain, I pay special attention to the histories and anthropological structures which inform the context noting that human rights discourses are heavily disputed both in history and contemporary times. This I suggest has bearing on the common average person’s access to, and relationship with, protected areas of culture such as medicine and law.

Questioning the Closed Nature of Medicine

The furtive silences that fall around psychiatry and the discussion of medical privilege prompt the need to examine some of the factors which amalgamate in the confluence of the medical juncture. There is an Omertà operating in a sociological and physiological tangle which, if unraveled, threatens some of the regimes of truth which are rehearsed as modern absolutes structuring our cultural landscapes. There is a deep discomfort with openly discussing the privilege of power and position as it suggests an unsettling of the order which is seen in the status quo and gives comfort to so many as the devil we know.

Sometimes the relationships which people have with medicine are more related to narcissist/co-dependency models than to ones of dialogue and honest candour. The epoch we live in is shaped and derived from anthropologies and histories where straight jacket’s and surgical procedures were used to restrain people – ‘to quiet people down’. Our lot is to live through the chemical-industrial age, one where the prescription pad is the gateway to psychoactive drugs given out in the chemistry addled world, one where ipse dixit reasonings are dished out like candies.

Dissidence as Madness

Dare we critique the eminent professionals which have been placed in positions of authority and power; job roles which entice parents from particular socio-economic backgrounds to hothouse and push young minds to abandon other aspirations for ‘a respectable profession’ ? Dare we question the nature of madness or the impulses behind behaviours when standing out oft recreates one as a target, as a dissenter and trouble maker ?

I guess it is something of a madness to query power from the bottom, and dissent has historically been met in many places and times by assertions of power. It is for your own good it is often uttered; these are acceptable trade offs it is often said… Is it fair even to raise these points when the eminent professions are sacred for good reason ? The dynamics of this I am going to explore, so I argue yes, with the correct intent – one which is oriented around constructive remedy rather than an instinct for pugilism.

This very idea of questioning power has an important place in the history of madness. There is something of relativism going on in the use of the term mad. It is used to devalue the content of people at times, it is used to express uncontrolled emotion at others, and at other times it can be used to express elation at something out of the ordinary. Examining how simple labels can invalidate individuals who have had them applied is a part of the journey we must undertake if we are to get to a true and just understanding of mental health and mental illness.

If we look at the context of Russia, historically political dissidents were labelled with the psychiatric label of ‘sluggish schizophrenia‘. In his book ‘Punitive Medicine’ Alexander Podrabinek reveals to the reader the history of this label and the way which medicine has been used as an instrument of punishment (Podrabinek, 1980). As a medical assistant in the Soviet Union Podrabinek committed to paper how psychiatry was used for the suppression of political dissent before he himself was arrested and went into exile. He documents how psychiatry can be a place where civil liberties are absent and how ‘dissidents and socially dangerous individuals’ were interred in the identity of ‘sluggish schizophrenia’, as happened with the author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

Podrabinek’s work illustrates how the psychiatric apparatus was complicit with the state wishes in Soviet Russia. This raises significant questions for other cultural contexts. We know, for example, that in America cultural dissidents such as civil rights protesters (Metzl, 2010) experienced psychiatry as a weapon revealing long and troubled ideological heritages that haunt the modern day.

“This book tells the story of how race gets written into the definition of mental illness. It uncovers the surprising ways anxieties about racial differences shape clinical encounters, even when the explicit races of doctors and patients are not at issue. The book also shows how historical concerns about racial protest reverberate through treatment institutions and subvert even well-intentioned efforts to diagnose people or to help them.

Ultimately, the book explores the processes through which American society equates race with insanity; and through which our definitions of both terms change as a result. It is well known, of course, that race and insanity share a long and troubled past. In the 1850s, American psychiatrists believed that African American slaves who ran away from their white masters did so because of a mental illness called drapetomania.

Medical journals of the era also described a condition called dysaesthesia aethiopis, a form of madness manifest by ‘rascality’ and “disrespect for the master’s property’ that was believed to be ‘cured’ by extensive whipping. Even at the turn of the twentieth century, leading academic psychiatrists shamefully claimed that ‘Negroes’ were ‘psychologically unfit’ for freedom.”

Metzl J. (2010). The Protest Psychosis : How Schizophrenia Became A Black Disease. Beacon Press.

However, when a political regime inters people, the power exercised can be easily be more easily identified (at least from the inside), but when such power is sublimed to the estate of the individual and family, power is not always so easily identified precisely because it is so close. Examples of the use of psychiatry as a weapon wielded in familial and community contexts are found in the histories of warehousing unmarried mothers (Robinson, 2016), ‘difficult’ family members (Wise, 2013), and gay people (Dickinson, 2016).

“Society assumed that marriage was the only acceptable way to bring up children, yet Maud considered marriage to be a symbol of subjection; she felt more strongly about this than about the risk of stigmatizing the children as bastards. She lied to them, in the cause of truth and independence for herself. Who are we to judge? Only her own family could – and did – do that. In some ways Maud’s decision may have been selfish, but it was made with conviction and integrity, and it worked for her.

From 1913 onwards, secrets like Maud’s and Fred’s might bring not only shame if they were revealed, but incarceration. That is when the Mental Deficiency Act was passed, with the euphemistic purpose of furthering and bettering provision ‘for the care of Feeble-Minded and other Mentally Defective Persons’. According to the Act, women could be deemed moral imbeciles as well as mental ones, and sent to an appropriate institution: a lunatic asylum. Moral imbeciles were defined as ‘persons who from an early age display some permanent mental defect coupled with strong vicious or criminal propensities’.

This chillingly included unmarried mothers who could not support themselves and were pregnant with their second (or later) child. Repeat offenders, in other words, whom the workhouses did not want to subsidize, or whose families had had enough of them. Under the terms of the Act, all it took for a moral imbecile to be committed if she was under twenty-one was a word from her parent or guardian. She did not even have to be medically diagnosed an imbecile. Her status as a young, abandoned and unmarried mother was enough. Those over twenty-one were in the treacherous hands of the Poor Law Guardians, who were often only too pleased to send them, with their babies, somewhere else.”

Robinson J. (2016), In The Family Way : Illegitimacy Between The Great War And The Swinging Sixties. Thorpe, Leicester, Chapter 1

“‘Oh yes, all those Victorian husbands getting their wives put away,’ said a good friend, when I told her my plans for a book about sane people being declared mad in the nineteenth century. Many others subsequently came out with something similar. But I hadn’t got very far into my initial archival dig when the variety of victims of malicious asylum incarceration became apparent; and it appeared that, anecdotally at least, this was slightly more likely to have been a problem for men than for women, certainly in the first sixty years of the century. As for those people who were indisputably mentally disordered, the mysterious lunatic in the attic was as likely to have been Bert as Bertha; the disturbed person in white in the moonlight on the Finchley Road would just as plausibly have been Andrew Catherick as Anne.

The following stories have been selected to highlight the range of people who had to fight for their liberty against the imputation of insanity. Presented roughly chronologically, the tales reveal the various definitions of madness put forward by the physicians, and the suggestions made by campaigners seeking reform of the asylum committal procedure. The stories bring to light, too, the protests that flared up periodically against the mad-doctors and the huge support shown for alleged victims of incarceration conspiracy.

What also emerges is a portrait of a bureaucracy – the Commissioners in Lunacy – that was failing to keep pace with both popular feeling and the views of the newspaper opinion-mongers. Above all, the ‘lunacy panics’ of the nineteenth century highlighted the fear that the English were sleepwalking into allowing the medical profession to curb individual freedom by labelling unconventional behaviour as a pathological condition, in need of cure or containment. ‘No rank in society is now exempt from the fear of being peculiar, the unwillingness to be, or to be thought, in any respect original,’ wrote John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty, published in 1859 – the year in which a series of notorious cases forced the government to appoint a Select Committee to probe the English lunacy laws.”

Wise S. (2013), Inconvenient People : Lunacy Liberty And The Mad-Doctors In Victorian England. Vintage Books, Preface

“On a winter evening in 1966, Percival Thatcher visited a public toilet on his way home from work in his family’s butcher’s shop in east London.1 Percival did not need to use the facilities in the public toilet; he was ‘looking for love’.2 Here an ‘exceptionally good looking young man’3 approached Percival and made a sexual advance towards him. When Percival responded to his advance, he was arrested – the young man was an undercover police officer. Percival was charged and subsequently convicted of importuning and conspiring to incite the police officer to ‘commit unnatural offences’.4

He was given the option of imprisonment or to be remanded provided he was willing to undergo psychological treatment to ‘cure’ his ‘condition’. In the belief that the psychological treatment would be a ‘better option’5 than imprisonment, he chose to receive the treatment. Percival was transferred to a local National Health Service (NHS) psychiatric hospital and was subjected to what he described as ‘a barbaric torture scene by the Gestapo in Nazi Germany trying to extract information from me’6 and he thought he ‘was going to die’.7

What Percival had agreed to was to undergo aversion therapy in a bid to cure him of his homosexuality. The behaviour of the police officer was not unusual and entrapment by undercover police officers during the 1950s and 1960s was common practice.8 Nurses were frequently involved in administering aversion therapies to cure such individuals of what were seen as their ‘sexual deviations’.9”

Dickinson T. (2016). ‘Curing Queers’ : Mental Nurses And Their Patients 1935-74. Manchester University Press

How do we disentangle the state from the individual and family or even community kinship relations ? Is it possible when the apparatus of the state is ultimately constructed and operated by individuals who inevitably come from a family nucleus and community relations ? What are the ideologies operating within the personal domain of the family nucleus and kith relations which are held as unquestionable much like the Soviet, American and British states demonstrated in their history ?

“The incarceration of free thinking healthy people in madhouses is spiritual murder, it is a variation of the gas chamber, even more cruel; the torture of the people being killed is more malicious and more prolonged. Like the gas chambers, these crimes will never be forgotten and those involved in them will be condemned for all time during their life and after their death.” – Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Quote in Punitive Medicine (Podrabinek, 1980)

Complicity: Scrutinising Rosemary Kennedy’s Story

Of course the problem is deeper, broader and more complex than is comfortable. Psychiatry speaks something of the views of society, its silences, its complicities, its fears of the unknown, the misunderstood, its malignancies… The power of a community to impose on people who do not ‘fit’ is a central axiom of group behaviour; this is discussed in relation to notions like absolute authority and social contract but also well detailed in the discipline of psychology. Pointed questions like ‘How many women have been medicalised – sectioned and/or drugged – for calling into question the bondage of marriage and the heritage of coverture ?’ are important to get beyond the inertia of deference to status quo.

What is done in the name of love and care is testimony to the capacity of human beings to be collectively ‘insane’ – a word which has its roots in ‘unhealthy’. What follows is an analysis of the early life of Rosemary Kennedy as a case study in complicity which reveals the horror possible through the power of psychiatric sanction. The sister of politician John F. Kennedy, her story illustrates how a series of unquestioned social realities ultimately gave rise to the lobotomisation of a young woman coming into the prime of her life.

When you read the biographies detailing what was known, it is apparent how the educational system, the institution of the family, the medical system, the church and government all participated in the effective destruction of this woman’s capacity to live an independent life. In short it is a high profile human rights travesty.

This human rights atrocity started in 1923 when Rosemary was five. She had been put in the Edward Devotion School kindergarten in Brookline where her teachers labelled her “intellectually disabled” and “deficient” due to her lagging behind her peers in the academic standards which were expected. This was how Rosemary was represented to her parents; she had been stated as a “retarded child”. Rosemary’s mother reportedly “did not like people who lagged behind or who were different” and had high aspirations for her.

[Chapter 3, Larson K. C. (2016). Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter. Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.]

It should be borne in mind how, at this time, the eugenics movement was in full swing. The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) founded by the renowned biologist, eugenicist and nazi sympathiser Charles B. Davenport was one of the leading organisers in the American Eugenics movement. It’s activities included collecting large archives of family pedigrees and sending field workers to analyze individuals at institutions like mental hospitals and orphanages across the US [“The Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (1910-1939)”. The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19.12.2022]. This was all bankrolled by the likes of the American financier and railroad executive E. H. Harriman, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Institution. [Edwin Black (9 November 2003). “Eugenics and the Nazis – the California connection”. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 19.12.2022]

To get a sense of how women and people were regarded in Massachusetts – the same state where Rosemary was in nursery school – at this time we can read a letter from the former lecturer in surgery at Harvard and senior surgeon at Boston City Hospital, George W. Gay who had been approached by the Massachusetts Commission for advice:

“The most feasible method of controlling women at present in this state is custodial supervision in an institution. Surgery offers an effectual preventative to conception, but it is not without some danger to life. With the male, however, there is a measure which is safe, practically painless, effective and free from any objections. Vasectomy … has been done a good many times with most satisfactory results to all concerned…. Your Commission is doubtless familiar with the admirable work which has been and is now being done by Dr. H. H. Goddard at Vineland, New Jersey….

Having spent a day there last year I became much interested in the results of his labors. They seemed to furnish undeniable evidence of the folly of allowing defectives to procreate. A large proportion of them are of no comfort or use to themselves or to society in general and moreover very many of them, as you well know, become public charges, for the support of whom you and I and everybody else who pays taxes have to foot the bills. This is all wrong and any experiment which is reasonable and practicable is worthy of trial.”

[collections.countway.harvard.edu/onview/exhibits/show/galtonschildren/eugenics-in-massachusetts]

Leading proponents of Eugenics including Charles Davenport, Henry H. Goddard, Harry H. Laughlin, and Madison Grant involved themselves in lobbying government for various ‘solutions’ to the problem of the ‘unfit’. Massachusetts had become a hotbed for this kind of thinking which we can see exemplified in this report on eugenic research from E. E. Southard, Harvard’s Bullard Professor of Neuropathology to the board of directors of the Eugenics Record Office in 1910:

“It is probable that Massachusetts is hardly surpassable in this country as a field for the study of eugenics, including under that name not only 1) eugenics proper, that is, the study of hereditary conditions tending to maintain society at par (the prevention of deterioration) but also 2) cacogenics, the study of hereditary forces tending to pull society down, as well as 3) the possibly Utopian variant, aristogenics, with its hope of elucidating the method by which the best stock is assembled and improved.”

[collections.countway.harvard.edu/onview/exhibits/show/galtonschildren/eugenics-in-massachusetts]

Rosemary Kennedy, for not coming up to one metric analysis or another, had been labelled mentally retarded by her teachers at the age of five in a state which had fully adopted eugenic ideologies. Her mother tried various social remedies to improve the academic performance of her daughter stating “one [child] may be smart in studies, one dull—one may be overconfident, another shy—and so a different approach must be made”. This was to shape the rest of her life affecting the way which Rosemary was treated by her parents, educational system, church and doctors.

[Chapter 3, Larson K. C. (2016). Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter. Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.]

The social pressures on the ambitious parents were high and the eugenic attitudes of the time and place meant that the attainment levels of the children reflected on them as public individuals and as a family embedded within a Catholic social structure. This resulted in the parents relentlessly seeking to ‘fix’ what they perceived in Rosemary as a pathology of under attainment.

As a Catholic family in the US they also had to negotiate the social pressures and prejudices the white anglo-saxon Protestant culture placed on them. For example, the father, Joe Senior had struggled to gain access to the social clubs which required certain invitations. This meant that they worked hard to try out anything on Rosemary which might change their daughter into the ‘high achiever’ they wanted. Here is an excerpt from Larson’s book ‘Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter‘ which brings into relief the social atmosphere of the time:

“Rose’s consultations with a variety of doctors, psychologists, psychiatrists, academic specialists, and religious leaders took on a new urgency. None offered Rose what she thought was best for Rosemary, making her ‘terribly frustrated and heartbroken.’ Rose was accustomed to controlling her children’s social and intellectual lives, and she was determined that Rosemary would not be separated from the family. Joe Sr. believed, too, that keeping Rosemary at home or enrolled in nearby private schools provided her with more benefits than an institution for the mentally disabled would.

Both of them clearly understood that in the socially elite circles of Boston, New York, Europe, and elsewhere the pressure to institutionalize Rosemary, a choice many of their similarly situated wealthy counterparts made for their disabled children, would be great. Rose and Joe’s peers had been influenced by the powerful eugenics movement that swept Western societies during the latter part of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Eugenics was fueled by pseudoscientific claims that the human race consisted of ‘two classes, the eugenic and the cacogenic (or poorly born).’ The cacogenic, eugenicists claimed, “inherited bad germ plasm, and thus as a group . . . at the very least, should not breed.’ African Americans, immigrants, the poor, and criminals were often deemed cacogenics; fears of the ‘immigrant hordes’ streaming into American cities and the migration of African Americans out of the Deep South into northern and western cities led some native-born white Americans to embrace these beliefs.

The intellectually and physically disabled were another category of ‘defectives.’ Eugenics scientists and their followers believed that these individuals were also the products of inherited bad genes and should be treated much the same way as the mentally ill, criminals, and the chronically poor. Forced sterilization, they argued, was society’s cure. Some believed that spending money on insane asylums, poorhouses, and other charitable and social institutions and programs serving the mentally ill and disabled only encouraged the propagation of ‘bad seeds.’

The parents of ‘defectives’ carried these bad genes—an idea that placed the blame and shame squarely on families. Some of the most prominent industrialists, scientists, and political leaders of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including President Teddy Roosevelt, supported these views. Wealthy industrialists John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, John Kellogg, Mary Williamson Harriman, and early feminist Victoria Woodhull became advocates of eugenics, funding spurious research promoting racial and ethnic discrimination through false claims of genetic deviance in nonwhite and ethnic minorities.

Labels such as ‘moron’ and ‘mental defective’ further complicated an already difficult life for Rosemary and her family. For Rose, reading eugenics literature and hearing such words describing her lovely daughter were stressful and heartbreaking. Christian beliefs and biblical tenets were no more helpful.

These overtly blamed parents for the physical, mental, and intellectual shortcomings and disabilities of their children, warning believers who failed to follow the Ten Commandments and the teachings of the Old Testament that God would punish them by ‘visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation.’ At that time the Roman Catholic Church routinely refused the sacraments of Holy Communion and Confirmation to intellectually disabled children, especially those with Down syndrome.”

[Chapter 3, Larson K. C. (2016). Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter. Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.]

“Rose [the mother] took her to ‘experts in mental deficiency,’ but their assessments and recommendations left Rose discouraged. The specialists told her that Rosemary had suffered from an unspecified ‘genetic accident,’ ‘uterine accident,’ ‘birth accident,’ and so forth.’ Some of Rosemary’s siblings believed that she also suffered from intermittent epileptic seizures. Eunice [the sister] remembered sudden and hurried calls to the doctor, who would rush to the house and administer injections and medications to Rosemary…

‘I can remember at the Cape the doctors coming in and giving her shots and then disappearing.’ Whenever one of these episodes occurred, the children were whisked away to another room or sent outside to wait until the doctor left, and only then were allowed to resume their activities. None of them dared ask what was wrong with Rosemary.

Gloria Swanson recalled Joe’s [the father] rage when she asked about Rosemary’s condition….They embarked on an illicit affair that lasted several years. Early in their liaison, Swanson overheard Joe talking on the phone with someone regarding the then ten-year-old Rosemary. He was ‘agitated’ and annoyed with the person on the other end of the line. Apparently, Joe was trying to get an unidentified doctor to treat Rosemary and ‘cure’ her. He offered to purchase a new ambulance for the hospital if the doctor would take Rosemary as a patient. The telephone call ended abruptly.

Swanson suggested that Joe bring Rosemary to meet with her personal physician in California, Dr. Henry G. Bieler. Bieler advocated a therapeutic diet as an alternative to drug therapies to cure a variety of illnesses. Swanson, like many other Hollywood stars, had followed his regimen and believed he held the key to lasting good health and mental well-being.

‘I had seen him [Joe] angry with other people, but now, for the first time, he directed his anger against me,’ Swanson wrote in her autobiography. ‘It was frightening. His blue eyes turned to ice and then to steel. He said they had taken Rosemary to the best specialists in the East. He didn’t want to hear about some three-dollar doctor in Pasadena who recommended zucchini and string beans for everything.’ Swanson persisted, encouraging him to consider Bieler. Joe reacted even more harshly: ‘I don’t want to hear about it! Do you understand me? Do you understand me?”

Drug Medications and Epilepsy

Before I go on to layer up the picture of the cultural context, I am going to first make explicit the physiological impacts which some of the drug medications would have had on the child Rosemary Kennedy. We can see that from an early age she was being exposed to ranging psychiatric drugs and treatments. The effects of early sedative medications like potassium bromide and barbiturates are well known. Kaculini, Tate-Looney, and Seifi (2021) give a history of anti-epileptic drugs and treatments which were popular in the context:

“At the turn of the 19th century, pharmacologic treatment of epilepsy began to gain traction. In 1912, Alfred Hauptmann discovered the anticonvulsant properties of phenobarbital, one of the most commonly prescribed medications for epilepsy worldwide today. Numerous Anti-Epileptic Drug’s were introduced in the following decades including ethosuximide, carbamazepine, valproate, and several benzodiazepines”

We can discover from scrutiny of standard pharmacological texts (such as the Rang and Dale and the British National Formulary), and drawing on fields such as toxicology, the liberal use of pharmaceuticals can create a range of problems which lead to iatrogenic harms through side effects that can get conflated with a prescribed psychiatric diagnosis. It does not take long to see that the list of drugs which have been used for epilepsy have wide ranging side effects including drowsiness, sedation, dizziness, lethargy, suicidal thoughts and behaviour etc.

Are teachers, clergy, parents, physicians and general society skilled enough in falsifiably distinguishing the effects of a drug from theorised conditions ? I would argue not particularly so when the drug gives rise to side effects which are attributed to the condition and where there are no scientifically detailed foundations for an organic basis of a condition against which checks can be made.

Excerpts from the Rang and Dale 8th Edition:

“Bromide was the first antiepileptic agent. Its propensity to induce sedation and other unwanted side effects has resulted in it being largely withdrawn from human medicine, although it is still approved for human use in some countries (e.g. Germany) and may have uses in childhood epilepsies.”

Carbamazepine

“Carbamazepine produces a variety of unwanted effects ranging from drowsiness, dizziness and ataxia to more severe mental and motor disturbances.4 It can also cause water retention (and hence hyponatraemia; Ch. 29) and a variety of gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side effects.”

Phenobarbital

“The main unwanted effect of phenobarbital is sedation, which often occurs at plasma concentrations within the therapeutic range for seizure control. This is a serious drawback, because the drug may have to be used for years on end. Some degree of tolerance to the sedative effect seems to occur, but objective tests of cognition and motor performance show impairment even during long-term treatment. Other unwanted effects that may occur with clinical dosage include megaloblastic anaemia (similar to that caused by phenytoin), mild hypersensitivity reactions and osteomalacia. Like other barbiturates, it must not be given to patients with porphyria (see Ch. 11). In overdose, phenobarbital depresses brain stem function, producing coma and respiratory and circulatory failure, as do all barbiturates.”

Ethosuximide

“Ethosuximide is well absorbed, and metabolised and excreted much like phenobarbital, with a plasma half-life of about 60 h. Its main side effects are nausea and anorexia, sometimes lethargy and dizziness, and it is said to precipitate tonic-clonic seizures in susceptible patients. Very rarely, it can cause severe hypersensitivity reactions.”

Phenytoin

“Side effects of phenytoin begin to appear at plasma concentrations exceeding 100pmol/l and may be severe above about 150|imol/l. The milder side effects include vertigo, ataxia, headache and nystagmus, but not sedation. At higher plasma concentrations, marked confusion with intellectual deterioration occurs; a paradoxical increase in seizure frequency is a particular trap for the unwary prescriber.”

Benzodiazepines

“Sedation is the main side effect of these compounds, and an added problem may be the withdrawal syndrome, which results in an exacerbation of seizures if the drug is stopped abruptly.”

Rang H. P. Dale M. M. Flower R. J. & Henderson G. (2016). Rang and dale’s pharmacology (Eighth). Elsevier Churchill Livingstone. Page 549 to 555

Excerpts from the British National Formulary 83rd Edition:

Phenobarbital (Page 364)

Agranulocytosis. anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. behaviour abnormal. bone disorders. bone fracture. cognitive impairment. confusion . depression. drowsiness. folate deficiency. hepatic disorders. memory loss. movement disorders. nystagmus. respiratory depression. severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs). skin reactions. suicidal behaviours

With oral use: Anxiety. hallucination. hypotension. megaloblastic anaemia. thrombocytopenia

Sodium valproate (Page 357)

Common or very common: Abdominal pain. agitation. alopecia (regrowth may be curly). anaemia. behaviour abnormal. concentration impaired. confusion. deafness. diarrhoea. drowsiness. haemorrhage. hallucination. headache. hepatic disorders. hypersensitivity. hyponatraemia. memory loss. menstrual cycle irregularities. movement disorders. nail disorder. nausea. nystagmus. oral disorders. seizures. stupor. thrombocytopenia. tremor. urinary disorders. vomiting. weight increased

Uncommon: Androgenetic alopecia. angioedema. bone disorders. bone fracture. bone marrow disorders. coma. encephalopathy. hair changes. hypothermia. leucopenia. pancreatitis. paraesthesia. parkinsonism. peripheral oedema. pleural effusion. renal failure. SIADH. skin reactions. vasculitis. virilism

Rare or very rare: Agranulocytosis. cerebral atrophy. cognitive disorder. dementia. diplopia. gynaecomastia. hyperammonaemia. hypothyroidism. infertility male. learning disability. myelodysplastic syndrome. nephritis tubulointerstitial. obesity. polycystic ovaries. red blood cell abnormalities. rhabdomyolysis. severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs). systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). urine abnormalities

Carbamazepine (P.335)

Common or very common: Dizziness. drowsiness. dry mouth. eosinophilia. fatigue. fluid imbalance. gastrointestinal discomfort. headache. hyponatraemia. leucopenia. movement disorders. nausea. oedema. Skin reactions. thrombocytopenia. vision disorders. vomiting. weight increased

Uncommon: Constipation. diarrhoea. eye disorders. tic. tremor

Rare or very rare: Aggression. agranulocytosis. albuminuria. alopecia. anaemia. angioedema. anxiety. appetite decreased. arrhythmias. arthralgia. azotaemia. bone disorders. bone marrow disorders. cardiac conduction disorders. circulatory collapse. confusion. congestive heart failure. conjunctivitis. coronary artery disease aggravated. depression. dyspnoea. embolism and thrombosis. erythema nodosum. fever. folate deficiency. galactorrhoea. gynaecomastia. haematuria. haemolytic anaemia. hallucinations. hearing impairment. hepatic disorders. hirsutism. hyperacusia. hyperhidrosis. hypersensitivity. hypertension. hypogammaglobulinaemia. hypotension. lens opacity. leucocytosis. lymphadenopathy. meningitis aseptic. muscle complaints. muscle weakness. nephritis tubulointerstitial. nervous system disorder. neuroleptic malignant syndrome. oral disorders. pancreatitis. paraesthesia. paresis. peripheral neuropathy. photosensitivity reaction. pneumonia. pneumonitis. pseudolymphoma. psychosis. red blood cell abnormalities . renal impairment. severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs). sexual dysfunction. speech impairment. spermatogenesis abnormal. syncope. systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). taste altered. tinnitus. urinary disorders. vanishing bile duct syndrome. vasculitis

Frequency not known: Bone fracture. colitis. human herpesvirus 6 infection reactivation. memory loss. nail loss. suicidal behaviours

Phenytoin (Page 351)

Agranulocytosis. bone disorders. bone fracture. bone marrow disorders. cerebrovascular insufficiency. coarsening of the facial features. confusion. constipation. dizziness. drowsiness. Dupuytren’s contracture. dysarthria. eosinophilia. fever. gingival hyperplasia (maintain good oral hygiene). granulocytopenia. hair changes. headache. hepatic disorders. hypersensitivity. insomnia. joint disorders. leucopenia. lip swelling. lymphatic abnormalities. macrocytosis. megaloblastic anaemia. movement disorders. muscle twitching. nausea. neoplasms. nephritis tubulointerstitial. nervousness. nystagmus. paraesthesia. Peyronie’s disease. polyarteritis nodosa. pseudolymphoma. sensory peripheral polyneuropathy. severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs). skin reactions. suicidal behaviours. systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). taste altered. thrombocytopenia. tremor. vertigo. Vomiting

Ethosuximide (Page 339)

Aggression. agranulocytosis. appetite decreased. blood disorder. bone marrow disorders. concentration impaired. depression. diarrhoea. dizziness . drowsiness. erythema nodosum. fatigue. gastrointestinal discomfort. generalised tonic-clonic seizure. headache. hiccups. leucopenia. libido increased. lupus-like syndrome. mood altered. movement disorders. nausea. nephrotic syndrome. oral disorders. psychosis. rash. sleep disorders. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. suicidal behaviours. vaginal haemorrhage. vision disorders. vomiting. weight decreased

Committee J. F. (2022). BNF 83 (British National Formulary) March 2022 (83th ed.). Pharmaceutical Press.

When we see the fact that Rosemary had highly charged helicopter parents who set high societal social standards and drilled their children to their aspirations, it only takes the myopia of an educator to trigger a chain of events which proved disastrous for the child. In an education system which plays children off each other in a high stakes competition – i.e. the availability of future opportunities – someone at the age of five may not be equaling the same cognitive metrics which other children score on and so get labelled ‘slow’ or something more toxic.

A logic problem exists with prescription happy doctors dishing out drugs which have as side effects the symptoms they purport to cure. The pharmaceutical industry is quick to experiment on people and promote drugs which have wide ranging consequences; we need only look at the court records over the decades to know this. Add to this the mix of over the counter medicines infused with the heady advertising of miracle treatments invented in the laboratories of esteemed scientists carries with it considerable dangers which damage people.

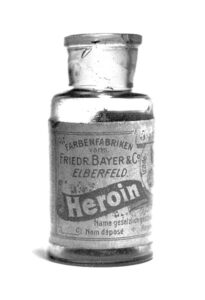

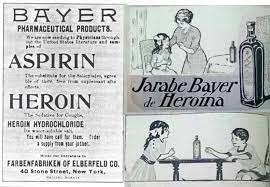

In the time Rosemary lived this a child might have been given any number of drugs which could have set the odds against them in any situation; as anyone who has tried sedatives might know, it is hard to function at your cognitive optimum when you are fighting the effects of drugs. Consider also that drugs such as heroine mixed with aspirin were being marketed and sold over the counter for children and adults for illnesses such as coughs and respiratory problems. You can see historical images illustrating this.

It is not unimaginable that Rosemary had a common childhood infection or minor ailment at some point in her young years and was medicated with a sedative medication which went on to impact her ‘academic performance’. It is also not unimaginable that she developed seizures from being given some sort of sedative medication due to the nature of many drugs producing profound biological shifts in state such as dependence, behavioural change and addiction/withdrawal symptoms.

This kind of iatrogenic feature of pharmaceuticals is not uncommon whereby the taking of one ‘medicine’ creates a different illness which is then subsequently medicated; but it is also not uncommon that medications which are given for a given symptom may also end up causing the given symptom – as illustrated in the case of some anti-epileptic medications.

Pharmacological Quagmire: The Sociology of the Medical Etiology

It is not enough to just look at the drugs to which this child was exposed but it is also important to construct a picture of how the medical world was constructing the etiology (causation or origination) of diagnoses alongside the cultural attitudes prevalent in the context. The cultural perception of seizures forged by the world of medicine had created pernicious and toxic images of people who suffered from seizures – many no doubt as a result of being exposed to some form of drug or another.

The work of Samuel-Auguste Tissot shaped medical discourse will into the last third of the nineteenth century. A reputed Calvinist Protestant neurologist, physician, professor and Vatican adviser, he had published ‘L’Onanisme: ou Dissertation Physique, sur les Maladies Produites par la Masturbation’ in 1764 which attributed epilepsy to masturbation.

[Lekka V. (2015). The neurological emergence of epilepsy : the national hospital for the paralysed and epileptic (1870-1895). Springer. Page 59]

“From this perspective, it should be noted that, during the first years under study, the methods of examination were, as one might have expected, rather embryonic, with the exception of the quite detailed categories ‘family history’ and ‘history’; in these two categories, the National Hospital’s doctors proceeded to the presentation and recording of even the minutest particulars of their epileptic patients’ personal life: from the their habits and their family tree to their potential proclivity to alcohol and the frequency of masturbation.”

[Lekka V. (2015). The neurological emergence of epilepsy : the national hospital for the paralysed and epileptic (1870-1895). Springer. Page 136]

It is well documented historically how the prevailing attitudes which dominated the ‘authority view’ of medicine prescribed to society how social and medical situations should be read. The notion of science had become a sort of totem by which values and attitudes could be projected on the world with impunity – a set of justifications which claimed to be objective and independent of the older vestiges of misapprehension, superstition and theocracy. The privileged culture of medicine was, and is, value laden whilst simultaneously denouncing, through an appeal to the ideal that scientific apprehension is free of such biases. Lekka details the kinds of social and cultural attitudes for us in the book ‘The Neurological Emergence of Epilepsy‘:

“Within the context of nineteenth-century hospital medicine, the practice of the persistent examination and measurement of the various bodily rates, the systematic observation, collection and recording of any kind of information, the constitution of the medical files, the strict definition of what constituted an anomaly and what a divergence from the ‘normal’, the pathologization of all ‘deviant’ states, the imposition of therapeutic/correctional/normative measures that aimed at the cure and, consequently, the generally accepted norm, constituted the regular beginning of every patient’s medical control and normalization.

Under these circumstances, a series of, until recently, putative ‘normal’ conditions of human life and, in a way, indifferent to power/knowledge networks, such as people’s birth, death, morbidity, disability, senility, even marital life, masturbation, mental health and childhood, all entered into the visual field of scientific medicine, being transformed into objects of medical research and intervention. At the same time, one of the most significant parameters of this procedure was health’s direct and obvious connection with what was considered as socially, politically, epistemologically and culturally ‘normal’, desirable and accepted.

Thus, it should not be considered as accidental the fact that medicine had primarily turned its attention to those social groups, which were generally considered as mostly threatening the social order and eurhythmy – among others, alcoholics, prostitutes, those suffering from venereal diseases, idiots, etc.; in other words, to those who were described as the ‘dangerous classes’. Without doubt, extremely indicative was the example of the so-called ‘mentally defectives’, to which epileptics were also included.

In late nineteenth century, within the frame of the general discussion on national degeneration and the emergent eugenic movement, mental deficiency emerged as a distinct medical, as well as social and political problem, marking the huge interest in both the human brain and the concept of the population. Everyone who was considered as a potential threat to the national prosperity and progress, was being rendered into an object of medical knowledge and, consequently, into the target of severe state intervention.

In this way, the category of the mentally defectives included a variety of people; beyond epileptics, it also included idiots, handicapped, deaf and blind persons, madmen, as well as criminals, alcoholics, those suffering from venereal diseases, etc. They were all treated as the result of the degeneration of their ancestors’ “pathological”, or even slightly “deviant”, condition. In this way, mentally defectives became gradually the archetypal representatives of the deterioration of the English race and the incarnated risk for its future.”

[Lekka V. (2015). The neurological emergence of epilepsy : the national hospital for the paralysed and epileptic (1870-1895). Springer. Page 156]

So we can see the attitudes which were likely projected onto the young Rosemary and how they also cast onto the Kennedy family in general. Whilst her father was fighting resistance to his inclusion in prestigious social clubs important for his political ambitions, the idea that one of his children was a mental defective would have been a weapon for others to use. We can see from the ‘History of Modern Epilepsy’ by Friedlander that the idea of sexual deviancy and its causing epilepsy had also been attributed to “parental masturbation”:

“W. Shanahan reviewed the status of this disorder in 1912, he noted that “research by means of the Wassermann test . . . [, discovered in 1906,] . . . into the part syphilis plays in epilepsy reveals the hereditary type as being present in a large percentage of cases developing in early life” [47]. Some other conditions which were supposed to predispose offspring to seizures were: changes in the nursing mother’s milk, due to excitement, anger [48] or worry [49]; parental masturbation [50]; puerperal convulsions [51]; and “traumatism” in a parent [4].”

[Friedlander W. J. (2001). The history of modern epilepsy : the beginning 1865-1914. Greenwood Press. Page 111]

“When a reason was offered about why excessive sexuality caused seizures, a frequent one was that it was irreligious and sinful. When a more physiological explanation was sought, a common one, using an 1892 quotation, was that there was an inordinate ‘expenditure of nerve force’ [203], or, as in a 1902 explanation, of ‘cerebral exhaustion’ [63].

Generally, masturbation was condemned more than excessive, but otherwise what was considered normal, sexual activity. Nothnagel, in 1877, made this point when he claimed that masturbation had a more marked effect on the nervous system than ‘excessive gratification of the sexual passion in the natural way’ [196]. Some relation between heredity and sexual activity’s epileptogenic nature was suggested by the idea that convulsions associated with an orgasm might be due to the inheritance of a ‘hypersensitive organization’ (‘nervous instability’ of Morel) [204].”

[Friedlander W. J. (2001). The history of modern epilepsy : the beginning 1865-1914. Greenwood Press. Page 124]

Add to all of this the fact that poor Rosemary was female, the notion of sexual agency in women was fraught taboo and therefore seizures may have resulted in a crucible of societal ills heaped on a young child which was to amount to the realisation of atrocities which befell her. We can start to construct how sociological cascades may be triggered on occasion which mount a series of societal projections on target individuals which sets the scene for moral disengagement and atrocity ? We can start to understand certain manifestations around and in psychiatry as social contagion.

“If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?” ― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918–1956 (Solzhenit︠s︡yn, 2018)

Complicity and Coalescence: The Social Model

The benefit of the doubt is too commonly extended to those at the top of junctures of power relations and this leads to harms. That doctors could have reinforced the painting of Rosemary Kennedy as ‘intellectually disabled’ at such a young age should appall us. Not only this but that the medications which were heaped on her through her years were never queried for their impacts on cognition and wellbeing; this is a cultural horror show – one which I suggest lasts into this age.

To top this, that the vain drives of parents and educators are not questioned and are privileged over the health and happiness of an individual is an age old travesty shored up by industries of people who cater to the production of societies of exclusion and the damages which come of these. Such provocations are important if we are to get to the bottom of the disasters of medicalisation.

It seems that the intellectual capabilities of Rosemary were fine if we compare them with average capacities of today. Here is a letter which she wrote to her father illustrating the kind of cognitive work which she had been doing in a private school, this time in Brookline. Translating French into English is no simple task; and anyone keeping a journal and maintaining a range of communications with her family and others suggest how capable this girl was.

October 1, 1934

Darling Daddy,

J’ai beaucoup travaille a vous donner plaisir.

I have a travel book about Europe, and I am looking up and answering all the questions.

I have a French book, called, ‘que Fait Gaston?’ I am sending you a few lines from it.

The book is written all in French, and I have to translate it.

I am learning some History way back in the beginning when men lived in caves, and did not even know how to cook . . .

Did you receive my postcards and my letter? I am going to take some dancing lessons to get ready for the first Dance.

I hope soon to send you a letter in French. Give my love to all the family.

Rosemary

Whilst people can rationalise that Rosemary Kennedy experienced seizures and violent mood swings, it seems to me to imagine that mood swings might have been an entirely appropriate response to her environment; a patriarchal society riddled with prejudice which assumed all sorts of toxic ideas of people – and girls – who did not respond and fit into the plans dictated for them. Imagine being told that the seizures you are having are due to your unconfessed sexual proclivities ? Imagine how psychologically damaging being told this by your family and doctors would be. Being told as a child that you are mentally deficient, and yet witnessing the madness’ of the society which was telling you this – it is like a dark Franz Kafka story.

Shunted from school to school, from physician to physician, in a world which treated women (and many groups of people placed at disadvantages) perversely, in a high pressure family with social ambitions of political and economic climbing – what was this young woman to do ? What do all healthy young people do when perceiving they are yoked by other people’s ideas of who they want you to be ? I would suggest push back.

Tensions grew in her life and as a maturing young woman she expressed beauty. This brought with it considerable frictions within a family which already had a problematic relationship with sexuality, no doubt inflamed by the doctrine and culture of both the Catholic church and the prevailing Protestantism at large.

Her mother Rose held the perspective that sex should only be engaged with for the purposes of procreation. This was consonant with the conservative teachings of the Catholic church which Rose vocally cited. The role of sexuality in the sociological configuration we are examining that ultimately impacted so violently on Rosemary Kennedy is very significant. It shaped many outcomes. The following is an excerpt from Larson’s book which gives insight into how Rose Kennedy viewed the issue of sex for pleasure:

“It is not clear how early in the marriage Rose’s devotion to a very conservative version of Catholic womanhood became a barrier to sexual intimacy. The church deplored ‘deliberate cultivation of sexual union as an end in itself’ and upheld ‘the primary purpose[s] for which marriage exists—namely, the continuation of the race through the gift and heritage of children; the other is the paramount importance in married life of deliberate and thoughtful self-control.’

One of Rose’s friends from those years, Marie Green, later recalled that Joe found Rose’s refusal to engage in sex for pleasure extremely frustrating. Green reported that Joe often teased Rose about her confined and restricted view of sex. ‘This idea of yours that there is no romance outside of procreation is simply wrong,’

Marie heard Joe saying to Rose during one of their Friday-night get-togethers playing cards. ‘It was not part of our contract at the altar, the priest never said that and the books don’t argue that,’ Joe claimed. But Rose was resolute, and, in spite of what Joe argued and wanted, she had church teachings to support her. Green later recalled that after the birth of the Kennedys’ ninth child, Edward ‘Teddy’ Moore Kennedy, in 1932, Rose told Joe, ‘No more sex.'”

[Chapter 2, Larson K. C. (2016). Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter. Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.]

“When Kick turned thirteen, in 1933, Rose shipped her off to boarding school. ‘She was tremendously popular with the boys,’ Rose later wrote, ‘who were always telephoning her and asking her on dates . . . So boarding school was the answer, no phone calls or distractions from study, with girls her own age and whose families we all know.’ Keeping her girls under control was a significant priority. There is no explicit record of Rose’s thoughts on Rosemary’s sexual maturation. She had read the literature of the era, however, on female ‘defectives’—how they were more likely to become promiscuous, to have children with similar disorders or worse, and to create a more dangerous ‘class’ of criminals, prostitutes, and ‘feebleminded’ offspring.”

[Chapter 4, Larson K. C. (2016). Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter. Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.]

Here in the following excerpt, Larson discusses the likely candidate for the red pills which Rosemary had written about in her diary that she been prescribed and taking for years; the excerpt also touches on the troubled responses to the sexual maturation of this young woman:

“Though there is no way to tell what type of seizures Rosemary suffered from, any kind would have been frightening, exhausting, and debilitating. Treatment at the time would have included some form of sedative, like Luminal, the addictive barbiturate in red-pill form that Rosemary may have already been taking for years, to calm her after the worst of a seizure was over. In those days, however, treatment for epilepsy and nonepileptic seizures was limited and mostly ineffectual. Rosemary’s striking beauty—lovely features, a broad, perfect smile, and a buxom figure—continued to attract men’s attention. Rosemary had proudly told her father earlier that summer that even that ‘Saks man’ told her ‘he thinks [sic] I am the best looking of the Kennedys.’

In a household both highly sexualized on the male side and notably repressed on the female side, Rosemary’s beauty was a special threat. Lem Billings [friend of the father and family] suggested an additional diagnosis to journalist Burton Hersh: Rosemary was ‘sexually frustrated,’ a view surely more telling about Billings’s own sexual outlook than Rosemary’s, but his belief was rooted in common views about intellectually disabled and mentally ill women—attitudes shared and feared by Rosemary’s parents.

Twenty years after women had finally gained the right to vote, society’s lingering nineteenth-century ideas played heavily on social, religious, and scientific attempts to control women’s more public and expressive sexuality. This had devastating consequences for the country’s most vulnerable and weakest women, mentally ill and disabled women who faced victimization through forced sterilization and institutionalization at alarming rates. Interestingly, in spite of being effervescent, outgoing, and flirtatious, the slim-figured Kick was viewed as less sexually suggestive than Rosemary.

Though open and frank about sex in conversation, Kick [the sister Kathleen ‘Kick’ Kennedy] had no experience with intimate sexual contact, and her male friends knew that her religious background would preclude her from engaging in any sort of premarital sexual activity. In fact, Kick wished privately to her best friend, Charlotte McDonnell, as many of her friends were ‘pairing up’ and getting married, that she could remain single forever and go to parties, instead, every night. Yet no male contemporary of Kick’s ever described this party girl as ‘sexually frustrated,’ and it was Rosemary’s potential and physically obvious sexuality that her parents found dangerous.”

The mother attempted to regulate Rosemary’s life through sending her to a series of schools and summer camps ensuring that she was watched all the time. Rose and Joe Snr (the parents) turned to the Catholic Church however historically the church offered little help to families with children suffering from intellectual and physical disabilities. It was in 1917 through the development of Benedictine monk Thomas Verner Moore’s project of Saint Gertrude’s School of Arts and Crafts that this faith community started to open its thoughts to offering support.

Moore cultivated a “clear vision of what the Catholic Church needed to do for its mentally disabled members,” and aimed to bring together science and faith in clinical and social service oriented approaches. With proximity to the Catholic University and Trinity College it served to train nuns and laypersons in special education for those with disabilities.

There, a clinical care center was established at the university for mental illness and disabled children with significant funding coming from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1939 along with money from wealthy Catholic donors. It would be a major site for Catholic professionals to conduct research for “the treatment of emotional and behavior disorders” and psychiatry.

In 1940 Rosemary was placed at Saint Gertrude’s which by that time had fully integrated with the Child Center at the university. Culturally lauded as a therapeutic setting, Rosemary’s presence for public appearances had been described to function as a teacher’s aide. Unfortunately Rosemary did not find this move to be therapeutic, her mother writing later that “disquieting symptoms began to develop” and there being “noticeable regression…her customary good nature gave way increasingly to tension and irritability”. Larson describes this period in the following excerpt:

“Her outbursts of rage came on more frequently and unpredictably. Rose’s [the mother] niece Ann Gargan—the daughter of Rose’s sister Agnes—later revealed that Rosemary had become incorrigible at Saint Gertrude’s. She defied the nuns, the staff, and their rules. ‘Many nights,’ Gargan told historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, ‘the school would call to say she was missing, only to find her out walking around the streets at 2 a.m.’ The nuns would bring her back, clean her up, and put her to bed. Her explanations about where she had been or what she had been doing made no sense, or else they made frightening sense.

‘Can you imagine what it must have been like,’ Gargan recalled, ‘to know your daughter was walking the streets in the darkness of the night, the perfect prey for an unsuspecting male?’. Joe Sr. expected his children to keep ‘out of the [newspaper] columns,’ granddaughter Amanda Smith recalled. His fears that Rosemary would end up as fodder for gossip columnists profoundly informed his and Rose’s efforts to keep her sequestered. What happened to Rosemary during that time has remained a mysterious and complicated story, with a thin trail of evidence and mostly conjectured interpretation.

Even family members remain mostly in the dark about what truly happened to Rosemary during her time at Saint Gertrude’s. Rosemary remained at Saint Gertrude’s through 1941. Joe, no longer ambassador but living in Palm Beach playing golf and keeping up with news of the war in Europe, had looked into having Rosemary attend Wyonegonic Camp in Denmark, Maine, during the summer of 1941, but there is no record of Rosemary having attended.”

[Chapter 7, Larson K. C. (2016). Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter. Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.]

Kennedy family chronicler Laurence Leamer wrote about Teddy Kennedy’s memories of Rosemary’s disposition and contrastingly moots the fears which she evoked in her parents:

“Teddy knew nothing of the difficulties his big sister was facing. He only knew that good Rosemary was his gentle friend. She was not rushing out on dates or off with her friends like his other big sisters. She was there, ready to talk to him and play. To him, she was a dream of what an older sister should be. ‘I just had the feeling of a sweet older sister … who was enormously cheerful, affectionate, loving perhaps even more so than some of the older ones,’ Teddy reflected. ‘She always seemed to have more time, and was always more available.’

Rosemary could have handled a menial job, but in 1941 there was no place for her to go. In recent months, she had begun to suffer from terrible mood swings. She had uncontrollable outbursts, her arms flailing and her voice rising to a pitch of anger. In the convent school in Washington the nuns were having a difficult time managing her. She sneaked out at night and returned in the early morning hours, her clothes bedraggled. The nuns feared that she was picking up men and might become pregnant or diseased.”

[Chaper 10, Leamer L. (2002). The Kennedy Men: 1901-1963 : The Laws of the Father (1st Perennial). Perennial.]

The family hysteria about public appearances and control over the activities of the first born daughter manifested especially around the sexuality of Rosemary. These deep fears are cited in Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book ‘The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys‘:

“Something had to be done, not only for Rosemary but for her mother, who could not rid herself of the fear that something terrible was going to happen to her daughter. ‘I was always worried,’ Rose later noted, ‘that she would run away from home someday or that she would go off with someone who would flatter her or kidnap her, as the kidnapping craze was on then.’ And beyond these concerns, there was the deeper fear that Rosemary would get pregnant. At twenty-one she stood five feet seven inches tall, with a full rounded figure, a clear complexion and excellent features. ‘She was the most beautiful of all the Kennedys,’ Ann Gargan recalls. “

[Goodwin, D. K, (1987) The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys, Simon and Schuster, Page 640]

Rosemary’s life had become a series of placements to be overseen by her parents and people in their employ. Studiously managed by her mother Rose and the Rolodex she kept on all details of her children’s life events, one cannot help but wonder how much aspirations and fears had eclipsed the real Rosemary in the thoughts and actions of her parents. Drawing again on ‘Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter’ we find an insight into the micromanaged conditions she was living under:

“Through family acquaintances, Rose found what she believed to be a positive placement, Camp Fernwood, in western Massachusetts. She approached its owners and directors, Grace and Caroline Sullivan, to discuss Rosemary. The two women were the daughters of Michael Henry Sullivan, an attorney and former chairman of the Boston School Committee. In 1909, he had become the youngest judge ever appointed to the bench in Massachusetts. Located along the shores of Plunkett Lake, in Hinsdale, Camp Fernwood was a Catholic summer sleepaway camp for girls ages six to sixteen.

Rosemary seemed excited about attending the camp and about what she might be doing there during the summer. She believed, and no doubt was told, that she would be a ‘junior counselor,’ teaching youngsters as she had done in England. ‘But isn’t it interesting,’ she wrote her father in London on the Fourth of July after arriving at the camp, ‘but [sic] me being a junior counsellor the first year. They thought I had experience [sic] in Arts, and Crafts in Europe. So, I am teaching it now. I have the younger girls. And another girl Alice Hill, as the bigger girl in Arts, and Crafts. So, the two of us run it.’

Rose should have given the Sullivan sisters some indication that Rosemary, an adult woman, was intellectually disabled, but it seems she did not share much with them—certainly not that the staff would need to monitor Rosemary every day to be sure she rested, ate properly, completed her tasks, and remained composed with the children; or that they would be called to calm her rages, to constantly reassure and compliment her, and to monitor her every move.

Whereas Kennedy family lore long perpetuated the myth that Rosemary was hired to be a counselor at the camp, Sullivan family records reveal a different story. In the spring of 1940, while Rosemary was still living in England and the Sullivan sisters met Rose in New York to discuss Rosemary’s placement, they were completely unaware of the extent of her disabilities. All they knew was that Rose was hoping her twenty-two-year-old daughter—who had received Montessori training in England to become a teacher’s assistant—could find a spot for the summer at the camp.

She would require, Rose told them, a special counselor to accompany her at all times. Rose did not explain fully why this was so necessary. Terry Marotta, Caroline Sullivan’s daughter, wrote that her mother later recalled that ‘she should have known the minute Mrs. Kennedy arrived [in New York] without her daughter that the girl was not as ‘able’ as Rose was leading them to believe.’ To Rose’s relief, the Sullivans accepted Rosemary into the camp program—not officially as a paid junior counselor, but rather as a camper who needed guidance herself.

In a July 1 letter from Rose’s secretary and the younger children’s governess, Elizabeth Dunn, to the Sullivan sisters, Dunn conveyed Rose’s requirement that the camp staff be ‘sure her [Rosemary’s] arch supporters are in her shoes correctly’ and that Rosemary sit at the ‘diet table if you can encourage her to.’ Additionally, Rosemary should ‘use Arts and Crafts Shop as much as possible. Have tennis lessons as often as practical,’ and ‘do exercises for her arches.’

These ‘very important’ instructions were the ones Rose chose to convey—not suggestions on how to handle an adult woman prone to anger, or likely to be ‘fierce’ with the children, or anxious about changes in her daily routine and environment. Clearly, in spite of her instructions concerning Rosemary, Rose gave little thought to the campers or to the abilities of Fernwood’s staff to cope with Rosemary. There were problems from the start.

One family friend later recalled that the Fernwood staff did not realize that Rosemary’s shoes were ill fitting until they noticed her feet bleeding. Frustrated, the Sullivan sisters took Rosemary to their own podiatrist in nearby Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to help relieve her intense discomfort. Rosemary may have consciously followed her mother’s instructions about putting on a positive public face and not complaining, but in this case she was clearly carrying the mandate to the extreme.

The sisters were shocked when they discovered that Rosemary did not properly dispose of her stained sanitary napkins but rather stored them in her camp trunk. They were deeply worried by Rosemary’s habit of wandering off. Caroline Sullivan, whom Rosemary called ‘Cow’ because she could not pronounce Caroline’s nickname, ‘Cal,’ eventually had Rosemary sleep in her private quarters, with a bed placed up against the door to prevent her from wandering off in the middle of the night. After three weeks, the Sullivans had had enough, and they requested that Rose come and take Rosemary home. Rose told them she could not come to the camp and that it was up to them to get Rosemary to New York”

Larson K. C. (2016), Chapter 6, Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter, Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

In this short verbatim excerpt I want to pick up on a few points in order to surface the concerns which are relevant to critical readings of the sociology. We can see dueling narratives at play about why Rosemary was going to the camp which the Sullivans ran. Rose, the mother, had created a veritable prison where all of Rosemary’s activity was overseen. The narrative with those whom Rosemary had been placed with was obviously different from the version which she herself encountered.

Believing that she was to be doing meaningful activity as a junior counselor practicing her skills, she had in fact been placed as a ward with people who were closely associated with the parents; this likely meant some level of extra communication between the Sullivans and the parents from which Rosemary was divorced. We can imagine emotional cataclysm which might be involved when Rosemary discovered that she was not going to exercise her Montessori teaching but was there as a subject.