Sexual Diversity Throughout Nature: A Primer

This post is a series of verbatim excerpts taken from the book ‘Biological Exuberance; Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity’ by Bruce Bagemihl, Ph.D. The excerpts are taken from the introduction and the beginning of chapter 1 in order to illustrate some of the themes which the book deals with and some of the sources.

This post is designed as a primer to get a sense of the diversity of sexual practices which run through the natural world as observed and documented by zoologists and scholars. Bagemihl’s book is especially helpful in examining how sexuality is depicted and obfuscated through the media. Thinking about the multitude of nature documentaries which have peppered the televisual experience over the decades, this book offers something special for those interested in deconstructing the televisual experience to reveal narratives.

Most of all this post is also a celebration of Bahemihl’s work showing nature and its diversity in relation to sexuality. It is also a celebration of nature in general, those living species which share the planet as a home. Interested parties are encouraged to buy a copy of the book in order to get a true sense of the scale and breadth of the work. The following text is a collection of unchanged extracts from the book…

Introduction

To help narrow the field, certain parameters have been chosen: only examples of homosexual behavior or transgender that have been scientifically documented, for example, are covered in this book (such documentation includes published reports in scientific journals and monographs, and/or firsthand observations by zoologists, wildlife biologists, and other trained animal observers, corroborated by multiple sources whenever possible).

Not only does this limit the number of species to be included (many more cases undoubtedly occur but have not been so documented), it establishes a uniform and verifiable platform of data on which to base further discussion. In addition, the book focuses primarily on mammals and birds —not because other types of animals are somehow less interesting or “important,” but simply because space and time limitations necessitate that not all species can be covered.

In addition to discussing an extensive array of species (nearly 300 mammals and birds), the book draws upon more than two centuries of scientific research. Some of the findings reported here in a few sentences represent literally lifetimes of work on the part of biologists, who often devote their entire careers to studying one very specific and complex aspect of one type of behavior, in one particular population of one particular species.

With this in mind, the book should be seen not as a final, definitive pronouncement on the subject, but rather as a beginning or overture, an invitation to further research and discussion. Any account of homosexuality and transgender in animals is also necessarily an account of human interpretations of these phenomena. Because animals cannot speak directly for themselves the way people can, we must rely on human observations of their behavior. This presents both special challenges and unique advantages to the study of the subject.

With people, we can often speak directly to individuals (or read written accounts) about what their sexuality and associated phenomena mean— and so get a sense of their emotional and motivational states—without necessarily being able to verify their actual sexual behaviors. With animals, in contrast, we can often directly observe their sexual (and allied) behaviors, but can only infer or interpret their meanings and motivations. As a result, many contentious assertions, theories, interpretations, and explanations have been put forward (and continue to be made) within the field of zoology about the function(s) and meaning(s) of homosexuality and transgender. This book seeks to address this historical and very human dimension of the subject, while still maintaining a focus on the animals, their behaviors and lives.

Furthermore, within this book such terminology is not used in a vacuum: it is accompanied by explicit discussion of the meanings of all such labels when applied to animals—including overt disavowal of their human connotations and extensive consideration of the inappropriateness of making unwarranted human-animal comparisons (see chapter 2).

I point out in Biological Exuberance that terminological debates themselves are not ahistorical—they reflect and embody very specific cultural and historical streams both within the scientific community and in society at large; they recapitulate (and lag behind) debates regarding “appropriate” terminology for homosexuality in humans; and the effect of such debates within the scientific discourse has often been to distract from the phenomena designated by such terms rather than to clarify them.

Next, the history of the scientific study of animal homosexuality is chronicled in chapter 3, “Two Hundred Years of Looking at Homosexual Wildlife.” This includes documentation of systematic prejudices within the field of zoology in dealing with this subject, which have often hampered our understanding of the phenomenon.

Chapter 4, “Explaining (Away) Animal Homosexuality,” continues the historical perspective by examining the many attempts to interpret and determine the “function” or “cause” of animal homosexuality and transgender. Most such efforts to find an “explanation” have failed outright or are fundamentally misguided—particularly when they try to show how homosexuality might contribute to heterosexual reproduction.

In the next chapter, “Not for Breeding Only,” animal life and sexuality are shown not to be organized exclusively around reproduction. A wide range of nonprocreative heterosexual activities are described and exemplified, as are the diverse ways that homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual, and transgendered animals structure their relationship to breeding.

Sexual and gender variance in animals offer a key to a new way of looking at the world, symbolic of the larger paradigm shifts currently underway in a number of natural and social sciences. On every continent, animals of the same sex seek each other out and have probably been doing so for millions of years. Homosexuality among primates, for example, has been traced back to at least the Oligocene epoch, 24-37 million years ago (based on its distribution among contemporary primates; Vasey 1995:195).

Some scientists place its original appearance even earlier in the evolutionary line leading to mammals, at around 200 million years ago (Baker and Bellis 1995:5), and it has probably existed for much longer among other animal groups. Vasey, P. L. (1995) “Homosexual Behavior in Primates: A Review of Evidence and Theory,” International Journal of Primatology 16:173-204; Baker, R., and M. A. Bellis (1995) Human Sperm Competition: Copulation, Masturbation, and Infidelity (London: Chapman and Hall).

They court each other, using intricate and beautiful mating dances that are the result of eons of evolution. Males caress and kiss each other, showing tenderness and affection toward one another rather than just hostility and aggression. Females form long-lasting pair-bonds—or maybe just meet briefly for sex, rolling in passionate embraces or mounting one another. Animals of the same sex build nests and homes together, and many homosexual pairs raise young without members of the opposite sex.

Other animals regularly have partners of both sexes, and some even live in communal groups where sexual activity is common among all members, male and female. Many creatures are “transgendered,” crossing or combining characteristics of both males and females in their appearance or behavior. Amid this incredible variety of different patterns, one thing is certain: the animal kingdom is most definitely not just heterosexual.

Homosexual behavior occurs in more than 450 different kinds of animals worldwide, and is found in every major geographic region and every major animal group. Same-sex courtship, sexual, pair-bonding, and /or parenting behaviors have been documented in the scientific literature in at least 167 species of mammals, 132 birds, 32 reptiles and amphibians 15 fishes, and 125 insects and other invertebrates, for a total of 471 species (see part 2 and appendix for a complete list).

These figures do not include domesticated animals (at least another 19 species; see the appendix), nor species in which only sexually immature animals/juveniles engage in homosexual activities (for a survey of the latter in mammals, see DAGG, A.I. (1984), Homosexual behaviour and female-male mounting in mammals—a first survey. Mammal Review, 14: 155-185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.1984.tb00344.x). For a number of reasons, this tally is likely to be an underestimate (especially for species other than mammals and birds, which are not as thoroughly covered): see chapter 3 for further discussion. It should also be pointed out that species totals may differ depending on the classificatory schema used; in some taxonomies, for example, animals that in this book are lumped together as subspecies are considered separate species (e.g., the various subspecies of Savanna Baboons, Flamingos, or Wapiti/Red Deer).

This roster also excludes a wide variety of other cases in which the evidence for homosexual activities is not definitive, such as:

1. species in which homosexual activity is suspected (and sometimes included in comprehensive surveys of homosexual behavior, such as Dagg 1984) but in which the sex of participants has not yet been coin-firmed (e.g., one-horned rhinoceros [Laurie 1982:323], yellow-bellied marmot [Armitage 1962:327], South African cliff swallow [Earlé 1985:46], band-tailed barbfhroat hummingbird [Harms and Ahumada 1992], calliope hummingbird [Armstrong 1988], ringed Parakeet [Hardy 1964]).

2. bird species in which supernormal clutches have been documented without any direct evidence of same-sex pairs (e.g., numerous gulls and other bird species; see note 70, chapter 4).

3. same-sex trios or joint parenting arrangements with little or no conclusive evidence of courtship, sex, or pair-bonding between the like-sexed coparenis (e.g., bobolink [Bollinger et al. 1986], various ducks. grouse [cf. note 11, this chapter] ).

4. bird species in which males associate in “pairs” or form “partnerships” with other males for joint displays during heterosexual courtships, but in which no overt courtship or sexual behavior occers between such partners or other same-sex individuals (e.g., several manakins of the genera Chiroxiphia, Pipra, Machaeropterus, and Masius—note however that males in these species often court “female-plumaged. birds, the sex of most of which has not been determined, while in two other species, some of these individuals have been determined to be males; wild turkey; king bird of paradise and possibly other birds of paradise. For further references, see McDonald 1989: (Trainer and McDonald 1993:779).

5. species in which the only form of documented “same-sex” activity involves individuals mounting heterosexual copulating pairs, such that the mounting activity is not necessarily limited to like-sexed individuals or the same-sex motivation/orientation is not clear (e.g., camel and Dagg 1981:92], Buller’s albatross [Warham 1967:129]).

6. species in which the only same-sex activity is mounting that appears to be exclusively aggressive in character with no sexual component (e.g., collared lemming, degu, ground squirrel; of. Dagg 1984 and sources cited therein; see also chapter 3 for further discussion of aggressive or “dominance” mounting and the difficulty of distinguishing this from sexual mounting); and species in which the only same-sex activities are “affectionate” behaviors or “platonic” companionships unaccompanied by either signs of sexual arousal or overt courtship or sexual behaviors.

7. other inconclusive cases, such as species reported in secondary sources as exhibiting homosexuality but whose original sources do not definitively document same-sex activity (e.g., avocets, reported in Terres [1980:813], with no mention of source, as engaging in homosexual mounting; Makkink [1936] and Hamilton [1975]— the most comprehensive primary field studies of this species and the most likely sources for this information—describe ritual mountings and masturbation “eruptive copulations”] but no homosexual mounting).

List of references

- Armitage, K. B. (1962) “Social Behavior of a Colony of the Yellow-bellied Marmut (Marmota flaviventris).” Animal Behavior 10:319-31

- Armstrong, D. P. (1988) “Persistent Attempts by a Male Calliope Hummingbird, Stellula calliope, to Copulate with Newly Fledged Conspecifics,” Canadian Field- Naturalist 102:259—60

- Bollinger, E. K., T. A. Gavin, C. J. Hibbard, and J. T. Wootton (1986) “Two Male Bobolinks Feed Young at the Same Nest,” Wilson Bulletin 98:154—56

- Dagg, A. I. (1984) “Homosexual Behavior and Female-Wale Mounting in Mammals—a First Survey,” Mammal Review 14:155—85

- Earlé, R. A. (1985) “A Description of the Social, Aggressive, and Maintenance Behavior of the South African Cliff Swallow Hirundo

(Aves: Hirundinidae),” Navorsinge van die nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein 5:37—50 - Gauthier-Pilters, H., and A. I. Dagg (1981) The Camel: Its Evolution, Ecology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

- Hardy, J.W. (1964) “Ringed Parakeets Nesting in Los Angeles, California,” Condor 65:445—47

- Harms, K. E., and J.A. Ahumada (1992) “Observations of an Adult Hummingbird Provisioning an Incubating Adult,” Wilson Bulletin 104:369-70

- Laurie, A. ( 1982) “Behavioral Ecology of the Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis),” Journal of Zoology, London 196:307—41

- Makkink, G. F. (1936) “An Attempt at an Ethogram of the European Avocet (Recurvirostra avosetta L.), With Ethological and Psychological Remarks,” Ardea 25:1-63

- McDonald, D. B. (1989) “Correlates of Male Mating Success in a Lekking Bird with Male-Male Cooperation,” Animal Behavior 37:1007 —22

- Terres, J. K. (1980) The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds (New York: Alfred A. Knopf)

- Trainer, J. M., and D. B. McDonald (1993) “Vocal Repertoire of the Long-tailed Manakin and Its Relation to Male-Male Cooperation,” Condor 95:769—81

- Warham, J. (1967) “Snares Island Birds,” Notornis 14:122—39.

It should come as no surprise, then, that animal homosexuality is not a single, uniform phenomenon. Whether one is discussing the forms it takes, its frequency, or its relationship to heterosexual activity, same-sex behavior in animals exhibits every conceivable variation.

For most people, “homosexuality” means one thing: sex. While it’s true that animals of the same gender often interact sexually with each other, this is only one aspect of same-sex expression. Animal homosexuality represents a vast and diverse range of activities: it is neither a monolithic nor an exclusively sexual phenomenon. This section offers a survey of the full range of homosexual activity found in the animal world, organized around five major behavioral categories: courtship, affection, sex, pair- bonding, and parenting.

A word on terminology is in order. In this book, heterosexuality is defined as courtship, affectionate, sexual, pair-bonding, and/or parenting behaviors between animals of the opposite sex, while homosexuality is defined as these same activities when they occur between animals of the same sex.

Courtship behavior is a common feature of homosexual interactions, occurring in nearly 40 percent of the mammals and birds in which same-sex activity has been observed. Same-sex courtship assumes a dizzying array of forms, and zoologists often use evocative or colorful names as the technical terms to designate these most striking of animal behaviors (which are usually part of heterosexual interactions as well).

Many species perform elaborate dances or kinetic displays, such as the “strutting” of female Sage Grouse, who spread their fanlike tails; or the spectacular acrobatics and plumage displays of Birds of Paradise and Superb Lyrebirds; or the courtship encounters of Cavies, who “rumba,” “rumble,” “rump,” and “rear” each other in an alliterative panoply of choreographed behaviors. In other cases, subtler poses, stylized postures, or movements are used, such as the foreleg kicking found in the courtship displays of many hoofed mammals; “rear-end flirtation” in male Nilgiri Langurs and Crested Black Macaques; ritual preening and bowing during courtship interactions in Penguins; “tilting” and “begging” postures in Black-billed Magpies; “jerking” by female Koalas; and “courtship feeding”—a ritual exchange of food gifts seen in same-sex (and opposite-sex) interactions among Antbirds, Black- headed and Laughing Gulls, Pukeko, and Eastern Bluebirds.

Sometimes two courting individuals perform mutual or synchronized displays, such as the “triumph ceremonies” of male Greylag Geese and Black Swans; the “mutual ecstatic” and “dabbling” displays of Humboldt and King Penguins, respectively; synchronous aquatic spiraling in male Harbor Seals and Orcas; the elaborate “leapfrogging” and “Catherine wheel” courtship displays by groups of Manakins; and synchronized wing-stretching and head-bobbing in homosexual pairs of Galahs. Many birds have breathtaking aerial displays, including tandem flying in Griffon Vultures, shuttle displays and “dive-bombing” in Anna’s Hummingbirds, “hover- flying” in Black-billed Magpies, “song-dancing” in Greenshanks, and the “bumblebee flight” of Red Bishop Birds.

Many animals of the same sex touch each other in ways that are not overtly sexual (they do not involve direct contact of the genitals) but that do nevertheless have clear sexual or erotic overtones. These are referred to as affectionate activities and are found in nearly a quarter of the animals in which some form of homosexual activity occurs. Although many of these behaviors (grooming, embracing, play-fighting) can occur in other contexts, their erotic nature in a same-sex context is usually obvious: the two animals may be visibly sexually aroused, the behavior may directly precede or follow homosexual copulation or courtship, or the affectionate activity may occur in a same-sex pair-bond.

One type of affectionate activity is simple grooming or rubbing. Male Lions “head-rub” and roll around with each other before having sex together; Bats such as Gray-headed Flying Foxes and Vampire Bats engage in erotic same-sex grooming and licking; male Mountain Sheep rub their horns and faces on other males, sometimes becoming sexually aroused; Whales and Dolphins stroke and rub each other with their flippers or tail flukes, as well as rub bodies together; while numerous primates such as Apes, Macaques, and Baboons frequently caress and groom each other in both sexual and nonsexual contexts.

A few birds such as Humboldt Penguins, Pukeko, Black-billed Magpies, and Parrots also indulge in preening—the avian equivalent of grooming—in their homosexual interactions or pair-bonds. Some animals also “kiss” each other: male African Elephants, female Rhesus Macaques, male West Indian Manatees and Walruses, female Hoary Marmots, and male Mountain Zebras (among others) all touch mouths, noses, or muzzles during their homosexual encounters.

Even some birds, such as Black-billed Magpies, engage in mutual beak-nibbling or “billing” as part of same-sex courtship. In primates, kissing (in both homosexual and heterosexual contexts) can bear a startling resemblance to the corresponding human activity: a number of species such as Squirrel Monkeys and Common Chimpanzees engage in full mouth-to-mouth contact, while male Bonobos kiss each other with “passionate” openmouthed kisses with considerable mutual tongue stimulation.

A number of mammals also engage in mock battles or “play-fights” that have erotic overtones. Although they superficially resemble aggressive behavior, these “battles” or “contests” do not involve any physical violence and are clearly distinguished from actual cases of aggressive or territorial behavior in these species. Male African Elephants, for example, frequently become sexually aroused and develop erections when they perform ritualized erotic jousting matches, while numerous hoofed mammals such as male Giraffes, Bison, Blackbuck antelopes, and Mule Deer mount each other during play-fights or ritualistic jousting. Among primates such as Orangutans, Gibbons, and Proboscis Monkeys, males sometimes engage in playful wrestling matches that can develop into sexual encounters, while male Australian and New Zealand Sea Lions also indulge in play-fighting combined with same-sex mounting.

Although play-fighting is most common among male mammals, female Cheetahs sometimes engage in “mock fighting” with each other as part of same-sex courtship sequences, while female (and male) Galahs and Orange-fronted Parakeets in same-sex pairs have playful “fencing bouts” with their bills.(For a general survey of play-fighting, see Aldis, O. (1975) Play Fighting. (New York: Academic Press). Many other types of affectionate and contactual behaviors occur between animals of the same sex. Sometimes animals gently bite, nibble, or chew on each other’s ears (female Hoary Marmots), or wings and chests (Gray-headed Flying Foxes), or rumps (male Dwarf Cavies), or necks (male Savanna Baboons).

Male African Elephants intertwine their trunks, while female Japanese Macaques sometimes suck each other’s nipples, and male Crested Black Macaques and Savanna Baboons affectionately pat or grab other males’ rear ends. Pairs of animals may sit, huddle, or lie together in close proximity, sometimes touching hands or putting an arm around the shoulder (female Gorillas, Squirrel Monkeys, and Japanese Macaques, male Siamangs), while male Hanuman Langurs “cuddle” together by sitting back-to-front, one male between the other’s legs with his partner’s hands resting on his loins.

Male Lions and female Long-eared Hedgehogs slide the lengths of their bodies along their partner’s, while male Bowhead Whales, Killer Whales, and Gray Seals roll their bodies over each other, and same-sex companions in Gray Whales and Botos swim side by side while gently touching each other with their fins. Some animals have developed unique forms of touching that combine several different types of affectionate activities along with courtship and sexual behaviors.

Male Giraffes engage in “necking”, a multifaceted activity that incorporates elements of play-fighting, courtship, and sexuality, in which they rub their necks along each other’s body while also licking, sniffing, and becoming sexually aroused by one another. In Giraffes and other species, these types of activities sometimes involve multiple animals interacting simultaneously in near “orgies” of bodily contact.

Spinner Dolphins, for example, participate in “wuzzles”—group sessions of mutual caressing and sexual activity (both same-sex and opposite-sex)—while West Indian Manatees have a similar sort of “free- for-all” group activity known as cavorting, which can involve rubbing, chasing, and sexual interactions, among many other activities. Among birds, Hammerheads, Acorn Woodpeckers, and Blue-bellied Rollers have ritualized bouts of courtship and mounting activity that may involve groups of individuals and both same-sex and opposite-sex partners.

Affectionate activity often leads to, or is inseparable from, overtly sexual behavior—defined here as any contact between two or more animals involving genital stimulation. Most same-sex interactions involve only two individuals at a time, but group sexual (and courtship) activity—involving anywhere from three or four (Giraffes, Lions) to six or more (Bowhead Whales, Mountain Sheep) partners— occurs in over 25 different species. The actual type of genital contact varies widely. Full penetration in male anal intercourse occurs in some species (for example, Orangutans, Rhesus Macaques, Bison, and Bighorn rams), while female penetration of various types occurs during lesbian interactions in Orangutans (insertion of the finger into the vagina), Bonobos (insertion of the erect clitoris into the vulva), and Bottlenose and Spinner Dolphins (insertion of a fin or tail fluke into the female’s genital slit).

Simple pelvic thrusting and rubbing of the genitals on the rump of the other animal is widespread in both male and female homosexual mounts (occurring in the Northern Fur Seal, Lion, and Proboscis Monkey, among others), and simple genital-to-genital touching is the form of homosexual (and heterosexual) contact in species where males do not have a penis (as in most birds, such as the Pukeko and Tree Swallow). A more unusual type of male homosexual contact involves various forms of non-anal penetration.

In Whales and Dolphins, both males and females have a genital slit or opening; when not aroused, the male’s penis is contained in the cavity leading to this slit. Homosexual activity in Bowhead Whales, Bottlenose Dolphins, and Botos sometimes involves insertion of the penis of one male into the genital slit of the other. Other more unusual forms of penetration have also been documented: male Botos occasionally insert the penis into a male partner’s blowhole (on the top of his head!), while male Orangutans have even been observed retracting their penis to form a sort of “hollow” or concavity that another male can penetrate.

Clitoral rubbing or other types of genital tribadism are found in female Bonobos, Gorillas, and Rhesus Macaques (among others), while males in several species (e.g., White-handed Gibbons, West Indian Manatees, and Gray Whales) rub their penises together or on each other’s body. In male Bonobos, mutual genital rubbing sometimes takes the form of an activity with the colorful name of “penis fencing,” in which the males hang suspended by their arms and rub their erect organs against each other.

Oral sex of various kinds also occurs in a number of species. This may involve actual sucking of genitals (fellatio between males in Bonobos, Orang-utans, Siamangs, and Stumptail Macaques); licking of genitals (cunnilingus in Common Chimpanzees, Long-eared Hedgehogs, and Kob antelopes; penis-licking in Thinhorn Sheep and Vampire Bats; genital licking in female Spotted Hyenas and male Cheetahs); mouthing, nuzzling, or “kissing” of genitals (female Gorillas, male Savanna Baboons, Crab-eating Macaques, and West Indian Manatees); and genital sniffing in female Pronghorns and Marmots as well as scrotal sniffing in Whiptail and Red-necked Wallabies.

Male Stumptail Macaques even perform mutual fellatio in a sixty-nine position, while males of a number of primate species (including Gibbons, Bonnet and Crested Black Macaques, and Nilgiri Langurs) sometimes actually eat or swallow their partner’s (or their own) semen—though usually after mutual genital rubbing or manual stimulation rather than oral sex. Ingestion of semen by both males and females during masturbation in heterosexual contexts also occurs among Golden Monkeys (Clarke 1991:371)

Dwarf Cavies and Rufous Bettongs occasionally indulge in anal licking, nuzzling, and sniffing with same-sex (and opposite-sex) partners. Another sort of “oral” sexual activity is called beak-genital propulsion and occurs among both male and female Bottlenose and Spinner Dolphins: one animal inserts its snout or “beak” into the genital slit of another, simultaneously stimulating and propelling its partner forward while swimming (a similar behavior in Orcas, involving simple nuzzling or touching of the genitals with the snout, is known as beak-genital orientation).

Another type of activity found during homosexual interactions is masturbation, in which one animal stimulates its own or its partner’s genitals with a finger, hand, foot, flipper, or some other appendage. For example, male Savanna Baboons often touch, grab, or fondle the genitals of another male—this behavior is known aptly as diddling—while male Bottlenose Dolphins and West Indian Manatees sometimes rub another male’s penis with their flippers.

Male Rhesus and Crested Black Macaques, female Gorillas, male Vampire Bats, female Proboscis Monkeys, and male Walruses sometimes masturbate themselves when mounting, courting, or interacting sexually with another animal of the same sex. Mutual masturbation in a side-by-side sixty-nine position occurs in female Crested Black Macaques, while male Bonnet and Stumptail Macaques masturbate each other and even fondle one another’s scrotums. Another form of mutual masturbation in these species involves two males backing up toward each other and fondling each other’s genitals between their legs.

In Bonobos and Common Chimpanzees, individuals often rub their anal and genital regions together while in this rump-to-rump position, prompting zoologists to give these behaviors names like “rump-rubbing” and “bump- rump.” Other more unusual forms of “manual” stimulation include mutual genital stimulation using trunks in female Elephants, and anal stimulation and penetration with fingers by male Common Chimpanzees, Siamangs, and Crab-eating Macaques.

Wild animals often form significant pair-bonds with animals of the same sex. Homosexual pair-bonding takes many different forms, but two broad categories can be recognized: “partners,” who engage in sexual or courtship activities with each other, and “companions,” who are bonded to each other but do not necessarily engage in overt sexual activity with one another. More than a third of the mammals and birds in which homosexual activity occurs have at least one of these types of same-sex bonding. The archetypal example of a “partnership” is the mated pair: two individuals who are strongly bonded to one another in a way that is equivalent to heterosexually paired animals of the same species.

Many forms of same-sex partnership are exclusive or monogamous, and partners may even actively defend their pair-bond against the intrusion of outside individuals (for instance in male Gorillas, female Japanese Macaques, and male Lions). Animals of the same sex sometimes also compete with each other for the attentions of homosexual partners, as in male Gorillas and Blue-winged Teals; female Orangutans, Japanese Macaques, and Orange-fronted Parakeets may even compete with males for “preferred” female partners.

Some partnerships, however, are “open” or nonmonogamous: female Bonobos and Rhesus Macaques, for instance, may have sexual relations with several different “favorite” partners or consorts (of both sexes). Males in homosexual pairs of Greylag Geese, Laughing Gulls, Humboldt Penguins, and Flamingos sometimes engage in “promiscuous” copulations with birds (male or female) other than their mate (heterosexual pairs in these species are also sometimes nonmonogamous). Another form of nonmonogamy occurs among lesbian pairs in a number of Gulls and other birds: one or both females sometimes mate with a male (while still maintaining their same-sex bond) and are thereby able to fertilize their eggs and become parents.

The second main type of homosexual pairing is the “companionship.” Two animals of the same sex may bond with each other, often spending most of their time together exclusive of the opposite sex, but they do not necessarily engage in recognizable courtship or sexual activities with each other. For example, older African Elephant bulls sometimes form long- lasting associations with a younger “attendant” male: these animals are loners, spending all their time with each other rather than with other Elephants, helping each other, and never engaging in heterosexual activity.

Sometimes more than two animals bond together, forming a “trio” (in either partnership or companionship form). This arrangement can consist of three animals all of the same sex who are bonded with each other, as occasionally happens among female Ring-billed Gulls and male African Elephants, White-tailed Deer, and Black-headed Gulls. Trios can also be bisexual, consisting of two females and one male (e.g., Canada Geese, Common Gulls, and Jackdaws) or two males and one female (Greylag Geese, Black Swans, Sociable Weavers); in Oystercatchers, both types occur. In either form of a bisexual trio, there is significant bonding, courtship, and/or sexual behavior between the two animals of the same sex.

This distinguishes such associations from heterosexual trios, in which two animals of the same sex are bonded with an opposite-sexed individual but not to each other. Same-sex trios of closely bonded male Greylag Geese or female Grizzly Bears are also sometimes known as triumvirates, while bisexual (and heterosexual) trios in Flamingos are called triads. In a few species, “quartets” involving simultaneous homosexual and heterosexual bonds between four individuals sometimes occur: in Greylag Geese and Black-headed Gulls, for instance, three males and a female sometimes bond with each other, while in Galahs, two males and two females may associate in a quartet with various bonding arrangements between them.

Same-sex pairs in many species (especially birds) raise young together. Not only are they competent parents, homosexual pairs sometimes actually exceed heterosexual ones in the number of eggs they lay, the size of their nests, or the skill and extent of their parenting. How are such animals able to have offspring in the first place if they are in homosexual associations? Many different strategies are used, including several in which one or both partners are the biological parent(s) of the young they raise together.

The most common parenting arrangement of this type is found in lesbian pairs of several Gull, Tern, and Goose species: one or both female partners copulate with a male to fertilize her eggs. No bonding or long-term association develops between the female and the male (who is essentially a “sperm donor” to the homosexual pair), and the youngsters are then jointly raised by both females without any assistance from a male parent.

In a number of cases, homosexual pairs raise young without being the biological parents of the offspring they care for. Some same-sex pairs adopt young: two female Northern Elephant Seals occasionally adopt and coparent an orphaned pup, while male Hooded Warblers and Black- headed Gulls may adopt eggs or entire nests that have been abandoned by females, and pairs of male Cheetahs occasionally look after lost cubs.

Sometimes female birds “donate” eggs to homosexual couples through a process known as parasitism: in many birds, females lay eggs in nests other than their own, leaving the parenting duties to the “host” couple. This occurs both within the same species, and (more commonly) across species, and usually involves heterosexual hosts.

Male pairs of Hooded Warblers, however, sometimes receive eggs from Brown-headed Cowbirds (and possibly also from females of their own species) in this way; within- species parasitism may also provide eggs for male pairs of Black-headed Gulls and female pairs in Roseate and Caspian Terns. The opposite situation is thought to occur in Ring-billed Gulls: researchers believe that some homosexually paired females actually lay eggs in nests belonging to heterosexual pairs. Finally, some birds in same-sex pairs take over or “kidnap” nests from heterosexual pairs (e.g., in Black Swans, Flamingos) or occasionally “steal” individual eggs (e.g., in Caspian and Roseate Terns, Black-headed Gulls); homosexual pairs in captivity also raise foster young provided to them.

In a detailed study of parental behavior by female pairs of Ring-billed Gulls, scientists found no significant differences in quality of care provided by homosexual as opposed to heterosexual parents. They concluded that there was not anything that male Ring-billed Gull parents provided that two females could not offer equally well (Ring-billed Gull (Conover 1989:148)). This case is not exceptional: homosexual parents are generally as good at parenting as heterosexual ones.

Examples of same-sex pairs successfully raising young have been documented in at least 20 species, and in a few cases, homosexual couples actually appear to have an advantage over heterosexual ones. In some bird species in which same-sex pairs are unable to obtain fertile eggs on their own (or in which homosexual parenting has yet to be observed in the wild), parenting skills have been demonstrated by supplying homosexual pairs with “foster” eggs or young in captivity. Same-sex pairs of Flamingos, White Storks, Black-headed Gulls, Steller’s Sea Eagles, Barn Owls, and Gentoo Penguins, for example, have all successfully hatched such eggs and/or raised foster chicks.

Pairs of male Black Swans, for example, are often able to acquire the largest and best-quality territories for raising young because of their combined strength. Such fathers—dubbed “formidable” adversaries by one scientist —consequently tend to be more successful at raising offspring than most heterosexual pairs (Black Swan (Braithwaite 1981:140—42); for more details, see chapter 5 and part 2.)

In addition to parenting by homosexual couples, some animals raise young in alternative family arrangements, usually a group of several males or females living together. Gorilla babies, for example, grow up in mixed- sex, polygamous groups where their mothers may have lesbian interactions with each other, while Pukeko and Acorn Woodpeckers live and raise their young in communal breeding groups where many, if not all, group members engage in courtship and sexual activities with one another (both same-sex and opposite-sex).

In such situations, individuals that engage in homosexual courtship or copulation activities may either reproduce directly because they also mate heterosexually (Pukeko), or they may assist members of their group in raising young without reproducing themselves (Acorn Woodpeckers). See chapter 5 for further discussion of homosexual activity in communal groups and the often complex relationship between “helpers” and same- sex activity.

Other alternative family constellations include bisexual trios (mentioned above), homosexual trios (as in Grizzly Bears, Dwarf Cavies, Lesser Scaup Ducks, and Ring-billed Gulls) where three mothers jointly parent their offspring, and even quartets, in which four animals of the same (Grizzlies) or both sexes (Greylag Geese) are bonded to each other and all raise their young together. In many species, young may also be raised in heterosexual trios, i.e., family units with three parents in which only opposite-sex bonding is present between the adults. See chapter 5 for some examples.

Finally, some animals that have homosexual interactions are “single parents.” Many female mammals, for example, that court or mate with other females also mate heterosexually and raise the resulting young on their own or in female-only groups (as is typical for exclusively heterosexual females in the same species as well).

This is especially prevalent among mammals with polygamous or promiscuous heterosexual mating systems, such as Kob and Pronghorn antelopes and Northern Fur Seals (where males, and sometimes females, usually mate with more than one partner). Males in many polygamous species are often bisexual as well, fathering offspring in addition to courting or mating with other males; typically, however, they do not actively parent their offspring regardless of whether they are bisexual or exclusively heterosexual. For discussion of single parenting in animals where two (heterosexual) parents usually raise the young, as well as examples of other heterosexual parenting arrangements that deviate from the species-typical pattern, see chapter 5.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Enomoto, T. (1974) “The Sexual Behavior of Japanese Monkeys.” Journal of Human Evolution 3:351–72.

*Fedigan, L. M. (1982) Primate Paradigms: Sex Roles and Social Bonds. Montreal: Eden Press.

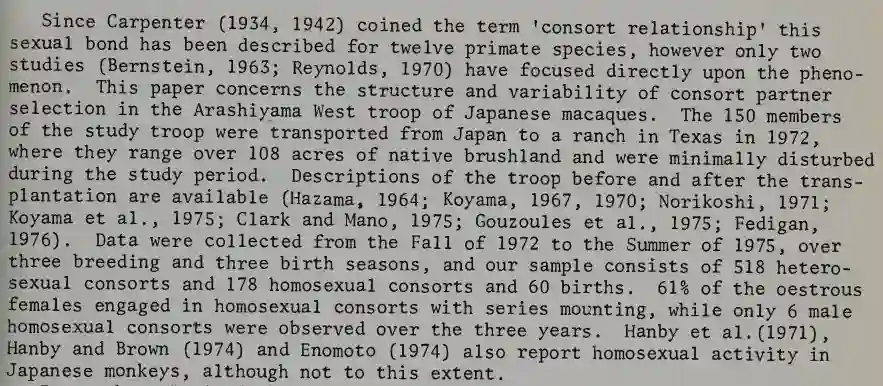

*Fedigan, L. M., and H. Gouzoules (1978) “The Consort Relationship in a Troop of Japanese Monkeys.” In D. Chivers, ed., Recent Advances in Primatology, vol. 1: pp. 493–95. London: Academic Press. Excerpt from text:

*Hanby, J. P., L. T. Robertson, and C. H. Phoenix (1971) “The Sexual Behavior of a Confined Troop of Japanese Macaques.” Folia Primatologica 16:123–43. Itani, J. (1959) “Paternal Care in the Wild Japanese Monkey, Macaca fuscata fuscata.” Primates 2:61–93.

*Takahata (1980) “The Reproductive Biology of a Free-Ranging Troop of Japanese Monkeys.” Primates 21:303–29. Takahata, Y., N. Koyama, and S. Suzuki (1995) “Do the Old Aged Females Experience a Long Postreproductive Life Span?: The Cases of Japanese Macaques and Chimpanzees.” Primates 36:169–80.

*———(1996–98) Personal communication.

Reptiles and Amphibians

Arnold, S. J. (1976) “Sexual Behavior, Sexual Interference, and Sexual Defense in the Salamanders Ambystoma maculatum, Ambystoma trigrinum, and Plethodon jordani.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 42:247– 300.

Bulova, S. J. (1994) “Patterns of Burrow Use by Desert Tortoises: Gender Differences and Seasonal Trends.” Herpetological Monographs 8:133–43.

Cole, C. J., and C. R. Townsend (1983) “Sexual Behavior in Unisexual Lizards.” Animal Behavior 31:724–28. Crews, D., and K. T. Fitzgerald (1980) “‘Sexual’ Behavior in Parthenogenetic Lizards (Cnemidophorous).” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 77:499–502. Crews, D., and L. J. Young (1991) “Pseudocopulation in Nature in a Unisexual Whiptail Lizard.” Animal Behavior 42:512–14.

Crews, D., J. E. Gustafson, and R. R. Tokarz (1983) “Psychobiology of Parthenogenesis.” In R. B. Huey, E. R. Pianka, and T. W. Schoener, eds., Lizard Ecology: Studies of a Model Organism, pp. 205–31. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Eifler, D. A. (1993) “Cnemidophorus uniparens (Desert Grassland Whiptail).Behavior.” Herpetological Review 24:150.

Greenberg, B. (1943) “Social Behavior of the Western Banded Gecko, Coleonyx variegatus Baird.” Physiological Zoology 16:110–22.

Hansen, R. M. (1950) “Sexual Behavior in Two Male Gopher Snakes.” Herpetologica 6:120.

Jenssen, T. A., and E. A. Hovde (1993) “Anolis carolinensis (Green Anole). Social Pathology.” Herpetological Review 24:58–59.

Kaufmann, J. H. (1992) “The Social Behavior of Wood Turtles, Clemmys insculpta, in Central Pennsylvania.” Herpetological Monographs 6:1–25.

Klauber, L. M. (1972) Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Liu, Ch’eng-Chao (1931) “Sexual Behavior in the Siberian Toad, Bufo raddei and the Pond Frog, Rana ni-gromaculata.” Peking Natural History Bulletin 6:43-60.

Mason, R. T. (1993) “Chemical Ecology of the Red-Sided Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis.” Brain Behavior and Evolution 41:261-68.

Mason, R. T., and D. Crews (1985) “Female Mimicry in Garter Snakes.” Nature 316:59–60.

Mason, R. T., H. M Fales, T. H. Jones, L. K. Pannell, J. W. Chinn, and D.Crews (1989) “Sex Pheromones in Snakes.” Science 245:290-93.

McCoid, M. J., and R. A. Hensley (1991) “Pseudocopulation in Lepidodactylus lugubris.” Herpetological Review 22:8-9.

Moehn, L. D. (1986) “Pseudocopulation in Eumeces laticeps.” Herpetological Review 17:40–41.

Moore, M. C., J. M. Whittier, A. J. Billy, and D. Crews (1985) “Male-like Behavior in an All-Female Lizard: Relationship to Ovarian Cycle.” Animal Behavior 33:284-89.

Mount, R. H. (1963) “The Natural History of the Red-Tailed Skink, Eumeces egregius Baird.” American Midland Naturalist 70:356–85.

Niblick, H. A., D. C. Rostal, and T. Classen (1994) “Role of Male-Male Interactions and Female Choice in the Mating System of the Desert Tortoise, Gopherus agassizii.” Herpetological Monographs 8:124–32.

Noble, G. K. (1937) “The Sense Organs Involved in the Courtship of Storeria, Thamnophis, and Other Snakes.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 73:673–725.

Noble, G. K., and H. T. Bradley (1933) “The Mating Behavior of Lizards; Its Bearing on the Theory of Sexual Selection.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 35:25–100.

Organ, J. A. (1958) “Courtship and Spermatophore of Plethodon jordani metcalfi” Copeia 1958:251-59.

Paulissen, M. A., and J. M. Walker (1989) “Pseudocopulation in the Parthenogenetic Whiptail Lizard Cneimidophorous laredoensis (Teiidae).” Southwestern Naturalist 34:296-98.

Shaw, C. E. (1951) “Male Combat in American Colubrid Snakes With Remarks on Combat in Other Colubrid and Elapid Snakes.” Herpetologica 7:149–68.

———(1948) “The Male Combat ‘Dance’ of Some Crotalid Snakes.” Herpetologica 4:137–45.

Tinkle, D. W. (1967) The Life and Demography of the Side-blotched Lizard, Uta stansburiana. Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology, no. 132. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Trivers, R. L. (1976) “Sexual Selection and Resource-Accruing Abilities in Anolis garmani.” Evolution 30:253–69.

Verrell, P., and A. Donovan (1991) “Male-Male Aggression in the Plethodontid Salamander Desmognathus ochrophaeus.” Journal of Zoology 223:203–12.

Werner, Y. L. (1980) “Apparent Homosexual Behavior in an All-Female Population of a Lizard, Lepidodactylus lugubris and Its Probable Interpretation.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 54:144–50.

Fishes

Aronson, L. R. (1948) “Problems in the Behavior and Physiology of a Species of African Mouthbreeding Fish.” Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences 2:33–42.

Barlow, G. W. (1967) “Social Behavior of a South American Leaf Fish, Polycentrus schomburgkii, with an Account of Recurring Pseudofemale Behavior.” American Midland Naturalist 78:215–34.

Carranza, J., and H. E. Winn (1954) “Reproductive Behavior of the Blackstripe Topminnow, Fundulus notatus.” Copeia 4:273–78.

Dobler, M., 1. Schlupp, and J. Parzefall (1997) “Changes in Mate Choice with Spontaneous Masculinization in Poecilia formosa.” In M. Taborsky and B. Taborsky, eds., Contributions to the XXV International Ethological Conference, p. 204. Advances in Ethology no. 32. Berlin: Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag.

Dominey, W. J. (1980) “Female Mimicry in Male Bluegill Sunfish—a Genetic Polymorphism?” Nature 284:546–48.

Duyvené de Wit, J. J. (1955) “Some Observations on the European Bitterling (Rhodeus amarus).” South African Journal of Science 51:249– 51.

Fabricius, E. (1953) “Aquarium Observations on the Spawning Behavior of the Char, Salmo alpinus.” Institute of Freshwater Research, Drottningholm, report 35:14–48.

Fabricius, E., and K.-J. Gustafson (1955) Observations on the Spawning Behavior of the Grayling, Thymallus thymallus (L.).” Institute of Freshwater Research, Drottningholm, report 36:75–103.

———(1954) “Further Aquarium Observations on the Spawning Behavior of the Char, Salmo alpinus L.” Institute of Freshwater Research, Drottningholm, report 35:58-104.

Fabricius, E., and A. Lindroth (1954) “Experimental Observations on the Spawning of the Whitefish, Coregonus lavaretus L., in the Stream Aquarium of the Hölle Laboratory at River Indalsälven.” Institute of Freshwater Research, Drottningholm, report 35:105–12.

Greenberg, B. (1961) “Spawning and Parental Behavior in Female Pairs of the Jewel Fish, Hemichromis bi-maculatus Gill.” Behavior 18:44–61. Morris, D. (1952) “Homosexuality in the Ten-Spined Stickleback.” Behavior 4:233–61.

Petravicz, J. J. (1936) “The Breeding Habits of the Least Darter, Microperca punctulata Putnam.” Copeia 1936:77–82. Schlosberg, H., M. C. Duncan, and B. Daitch (1949) “Mating Behavior of Two Live-bearing Fish Xiphophorous helleri and Platypoecilus maculatus.” Physiological Zoology 22:148–61.

Schlupp, I., J. Parzefall, J. T. Epplen, I. Nanda, M. Schmid, and M. Schartl (1992) “Pseudomale Behavior and Spontaneous Masculinization in the All-Female Teleost Poecilia formosa (Teleostei: Poeciliidae).” Behavior 122:88–104.

Insects

Aiken, R. B. (1981) “The Relationship Between Body Weight and Homosexual Mounting in Palmacorixa nana Walley (Heteroptera: Corixidae).” Florida Entomologist 64:267–71.

Alcock, J. (1993) “Male Mate-Locating Behavior in Two Australian Butterflies, Anaphaeis java teutonia (Fabricius) (Pieridae) and Acraea andromacha andromacha (Fabricius) (Nymphalidae).” Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 32:1–7.

Alcock, J., and S. L. Buchmann (1985) “The Significance of Post-Insemination Display by Males of Centris pallida (Hymenoptera: Anthophoridae).” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 68:231–43.

Alexander, R. D. (1961) “Aggressiveness, Territoriality, and Sexual Behavior in Field Crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllidae).” Behavior 17:130– 223.

Allsopp, P. G., and T. A. Morgan (1991) “Male-Male Copulation in Antitrogus consanguineus (Blackburn) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae).” Australian Entomological Magazine18(4):147–48.

Anderson, J. R., A. C. Nilssen, and I. Folstad (1994) “Mating Behavior and Thermoregulation of the Reindeer Warble Fly, Hypoderma tarandi L. (Diptera: Oestridae).” Journal of Insect Behavior 7:679–706.

Arita, L. H., and K. Y. Kaneshiro (1983) “Pseudomale Courtship Behavior of the Female Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann).” Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society 24:205–10.

Barrows, E. M., and G. Gordh (1978) “Sexual Behavior in the Japanese Beetle, Popillia japonica, and Comparative Notes on Sexual Behavior of Other Scarabs (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae).” Behavioral Biology 23:341– 54.

Barth, R. H., Jr. (1964) “Mating Behavior of Byrsotria fumigata (Guerin) (Blattidae, Blaberinea).” Behavior 23:1–30.

Bennett, G. (1974) “Mating Behavior of the Rosechafer in Northern Michigan (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae).” Coleopterists Bulletin 28:167–68.

Benz, G. (1973) “Role of Sex Pheromone and Its Insignificance for Heterosexual and Homosexual Behavior of Larch Bud Moth.” Experientia 29:553–54.

Berlese, A. (1909) Gli insetti: loro organizzazione, sviluppo, abitudini, e rapporti coll’uomo. Vol. 2 (Vita e cos-tumi). Milano: Società Editrice Libraria.

Bologna, M. A., and C. Marangoni (1986) “Sexual Behavior in Some Palaearctic Species of Meloe (Coleoptera, Meloidae).” Bollettino della Società Entomologica Italiana 118(4–7):65–82.

Bristowe, W. S. (1929) “The Mating Habits of Spiders with Special Reference to the Problems Surrounding Sex Dimorphism.” Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1929:309–58.

Brower, L. P., J. V. Z. Brower, and F. P. Cranston (1965) “Courtship Behavior of the Queen Butterfly, Danaus gilippus berenice (Cramer).” Zoologica 50:1-39.

Cane, J. H. (1994) “Nesting Biology and Mating Behavior of the Southeastern Blueberry Bee, Habropoda laboriosa (Hymenoptera: Apoidea).” Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 67:236-41.

Carayon, J. (1974) “Insémination traumatique hétérosexuelle et homosexuelle chez Xylocoris maculipennis (Hem. Anthocoridae).” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences, Série D—Sciences naturelles 278:2803–6.

———(1966) “Les inséminations traumatiques accidentelles chez certains Hémiptères Cimicoidea.” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences, Série D—Sciences naturelles 262:2176–79.

Castro, L., M. A. Toro, and C. Fanjul-Lopez (1994) “The Genetic Properties of Homosexual Copulation Behavior in Tribolium castaneum: Artificial Selection.” Genetics Selection Evolution (Paris) 26:361–67.

Constanz, G. (1973) “The Mating Behavior of a Creeping Water Bug, Ambrysus occidentalis (Hemiptera: Naucoridae).” American Midland Naturalist 92:230–39.

Cook, R. (1975) “‘Lesbian’ Phenotype of Drosophila melanogaster?” Nature 254:241-42.

David, W. A. L., and B. O. C. Gardiner (1961) “The Mating Behavior of Pieris brassicae (L.) in a Laboratory Culture.” Bulletin of Entomological Research 52:263–80.

Dunkle, S. W. (1991) “Head Damage from Mating Attempts in Dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera).” Entomological News 102:37–41.

Dyte, C. E. (1989) “Gay Courtship in Medetera.” Empid and Dolichopodid Study Group Newsheet 6:2–3.

Field, S. A., and M. A. Keller (1993) “Alternative Mating Tactics and Female Mimicry as Post-Copulatory Mate-Guarding Behavior in the Parasitic Wasp Cotesia rubecula.” Animal Behavior 46:1183–89.

Finley, K. D., B. J. Taylor, M. Milstein, and M. McKeown (1997) “dissatisfaction, a Gene Involved in Sex-Specific Behavior and Neural Development of Drosophila melanogaster.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 94:913–18.

Fleming, W. E. (1972) Biology of the Japanese Beetle. U.S. Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin no. 1449. Washington, D.C.: Agricultural Research Service.

Fletcher, L. W., J. J. O’Grady Jr., H. V. Claborn, and O. H. Graham (1966) “A Pheromone from Male Screwworm Flies.” Journal of Economic Entomology 59:142–43.

Forsyth, A., and J. Alcock (1990) “Female Mimicry and Resource Defense Polygyny by Males of a Tropical Rove Beetle, Leistotrophus versicolor (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 26:325–30.

Gadeau de Kerville, H. (1896) “Perversion sexuelle chez des Coleopteres mâles.” Bulletin de la Société Entomologique de France 1896:85–87.

Gill, K. S. (1963) “A Mutation Causing Abnormal Courtship and Mating Behavior in Males of Drosophila melanogaster.” American Zoologist 3:507.

Hanks, L. M., J. G. Millar, and T. D. Paine (1996) “Mating Behavior of the Eucalyptus Longhorned Borer (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and the Adaptive Significance of Long ‘Horns.’ ” Journal of Insect Behavior 9:383–93.

Harari, A. R. (1997) “Mating Strategies of Female Diaprepes abbreviatus (L.).” In M. Taborsky and B. Taborsky, eds., Contributions to the XXV International Ethological Conference, p. 222. Advances in Ethology no. 32. Berlin: Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag.

Harris, V. E., and J. W. Todd (1980) “Temporal and Numerical Patterns of Reproductive Behavior in the Southern Green Stinkbug, Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae).” Entomologia Experimentalis etApplicata 27:105–16.

Hayes, W. P. (1927) “Congeneric and Intergeneric Pederasty in the Scarabaeidae (Coleop.).” Entomological News 38:216–18.

Heatwole, H., D. M. Davis, and A. M. Wenner (1962) “The Behavior of Megarhyssa, a Genus of Parasitic Hymenopterans (Ichneumonidae: Ephilatinae).” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 19:652–64.

Henry, C. (1979) “Acoustical Communication During Courtship and Mating in the Green Lacewing, Chrysopa carnea (Neuroptera; Chrysopidae).” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 72:68– 79.

Humphries, D. A. (1967) “The Mating Behavior of the Hen Flea Ceratophyllus gallinae (Schrank) (Siphonaptera: Insecta).” Animal Behavior 15:82–90.

Iwabuchi, K. (1987) “Mating Behavior of Xylotrechus pyrrhoderus Bates (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). 5. Female Mounting Behavior.” Journal of Ethology 5:131–36.

Laboulmène, A. (1859) “Examen anatomique de deux Melolontha vulgaris trouvés accouplés et paraissant du sexe mâle.” Annales de la Société Entomologique de France 1859:567–70.

LeCato, G. L., III, and R. L. Pienkowski (1970) “Laboratory Mating Behavior of the Alfalfa Weevil, Hypera postica.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 63:1000–7.

Leong, K. L. H. (1995) “Initiation of Mating Activity at the Tree Canopy Level Among Overwintering Monarch Butterflies in California.” Pan- Pacific Entomologist 71:66–68.

Leong, K. L. H., E. O’Brien, K. Lowerisen, and M. Colleran (1995) “Mating Activity and Status of Overwintering Monarch Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Danaidae) in Central California.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 88:45–50.

Loher, W., and H. T. Gordon (1968) “The Maturation of Sexual Behavior in a New Strain of the Large Milkweed Bug Oncopeltus fasciatus.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 61:1566–72.

Mathieu, J. (1967) “Mating Behavior of Five Species of Lucanidae (Coleoptera: Insecta).” American Zoologist 7:206.

Matthiesen, F. A. (1990) “Comportamento sexuale outros aspectos biologicos da barata selvagem, Petasodes dominicana Burmeister, 1839 (Dictyoptera, Blaberidae, Blaberinae).” Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 34(2):261–66.

Maze, A. (1884) “Communication.” Journal officiel de la République française 2:2103.

McRobert, S., and L. Tompkins (1988) “Two Consequences of Homosexual Courtship Performed by Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila affinis Males.” Evolution 42:1093–97.

———(1983) “Courtship of Young Males Is Ubiquitous in Drosophila melanogaster.” Behavior Genetics 13:517–23.

Mika, G. (1959) “Uber das Paarungsverhalten der Wanderheuschrecke Locusta migratoria R. und F. und deren Abhängigkeit vom Zustand der inneren Geschlechtsorgane.” Zoologische Beiträge 4:153–203.

Nakamura, H. (1969) “Comparative Studies on the Mating Behavior of Two Species of Callosobruchus (Coleoptera: Bruchidae).” Japanese Journal of Ecology 19:20–26.

Napolitano, L. M., and L. Tompkins (1989) “Neural Control of Homosexual Courtship in Drosophila melanogaster.” Journal of Neurogenetics 6:87– 94.

Noel, P. (1895) “Accouplements anormaux chez les insectes.” Miscellanea entomologica 1:114.

Obara, Y. (1970) “Studies on the Mating Behavior of the White Cabbage Butterfly, Pieris rapae crucivora Boisduval. III. Near-Ultra-Violet Reflection as the Signal of Intraspecific Communication.” Zeitschrift für vergleichende Physiologie 69:99–116.

Obara, Y., and T. Hidaka (1964) “Mating Behavior of the Cabbage White, Pieris rapae crucivora. I. The ‘Flutter Response’ of the Resting Male to Flying Males.” Zoological Magazine (Dobutsugaku Zasshi) 73:131–35.

O’Neill, K. M. (1994) “The Male Mating Strategy of the Ant Formica subpolita Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Swarming, Mating, and Predation Risk.” Psyche 101:93–108.

Palaniswamy, P., W. D. Seabrook, and R. Ross (1979) “Precopulatory Behavior of Males and Perception of Potential Male Pheromone in Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 72:544–51.

Pardi, L. (1987) “La ‘pseudocopula’ delle femmine di Otiorrhynchus pupillatus cyclophtalmus (Sol.) (Coleoptera Curculionidae).” Bollettino dell’Istituto di Entomologia “Guido Grandi” della Università degli Studi di Bologna 41:355–63.

Parker, G. A. (1968) “The Sexual Behavior of the Blowfly, Protophormia terraenovae R.-D.” Behavior 32:291–308. Peschke, K. (1987) “Male Aggression, Female Mimicry and Female Choice in the Rove Beetle, Aleochara curtula (Coleoptera, Staphylinidae).” Ethology 75:265–84.

Pinto, J. D., and R. B. Selander (1970) The Bionomics of Blister Beetles of the Genus Meloe and a Classification of the New World Species. University of Illinois Biological Monographs no. 42. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Piper, G. L. (1976) “Bionomics of Euarestoides acutangulus (Diptera: Tephritidae).” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 69:381– 86.

Prokopy, R. J., and J. Hendrichs (1979) “Mating Behavior of Ceratitis capitata on a Field-Caged Host Tree.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 72:642–48.

Qvick, U. (1984) “A Case of Abnormal Mating Behavior of Dolichopus popularis Wied. (Diptera, Dolichopodidae).” Notulae Entomologicae 64:93.

Rich, E. (1989) “Homosexual Behavior in Three Melanic Mutants of Tribolium castaneum.” Tribolium Information Bulletin 29:99–101.

Rocha, I. R. D. (1991) “Relationship Between Homosexuality and Dominance in the Cockroaches, Nauphoeta cinerea and Henchoustedenia flexivitta (Dictyoptera, Blaberidae).” Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 35(1):1–8.

Rothschild, M. (1978) “Hell’s Angels.” Antenna 2:38–39.

Sanders, C. J. (1975) “Factors Affecting Adult Emergence and Mating Behavior of the Eastern Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (Lepidoptera: Totricidae).” Canadian Entomologist 107:967–77.

Schaner, A. M., P. D. Dixon, K. J. Graham, and L. L. Jackson (1989) “Components of the Courtship-Stimulating Pheromone Blend of Young Male Drosophila melanogaster: (Z)-13-tritriacontene and (Z)-11- tritriacontene.” Journal of Insect Physiology 35:341–45.

Schlein, Y., R. Galun, and M. N. Ben-Eliahu (1981) “Abstinons: Male- Produced Deterrents of Mating in Flies.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 7:285–90.

Schmieder-Wenzel, C., and G. Schruft (1990) “Courtship Behavior of the European Grape Berry Moth, Eu-poecilia ambiguella Hb. (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae) in Regard to Pheromonal and Tactile Stimuli.” Journal of Applied Entomology 109:341–46.

Serrano, J. M., L. Castro, M. A. Torro, and C. López-Fanjul (1991) “The Genetic Properties of Homosexual Copulation Behavior in Tribolium castaneum: Diallel Analysis.” Behavior Genetics 21:547–58.

Shah, N. K., M. C. Singer, and D. R. Syna (1986) “Occurrence of Homosexual Mating Pairs in a Checkerspot Butterfly.” Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 24:393.

Shapiro, A. M. (1989) “Homosexual Pseudocopulation in Eucheira socialis (Pieridae).” Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 27:262.

Simon, D., and R. H. Barth (1977) “Sexual Behavior in the Cockroach Genera Periplaneta and Blatta. I. Descriptive Aspects. II. Sex

Pheromones and Behavioral Responses.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 44:80–107, 162–77.

Spence, J. R., and R. S. Wilcox (1986) “The Mating System of Two Hybridizing Species of Water Striders (Gerridae).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 19:87–95.

Spratt, E. C. (1980) “Male Homosexual Behavior and Other Factors Influencing Adult Longevity in Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) and T. confusum Duval.” Journal of Stored Products Research 16:109–14.

Syrajämäki, J. (1964) “Swarming and Mating Behavior of Allochironomus crassiforceps Kieff. (Dipt., Chironomidae).” Annales Zoologici Fennici 1:125–45.

Tauber, M. J. (1968) “Biology, Behavior, and Emergence Rhythm of Two Species of Fannia (Diptera: Muscidae).” University of California Publications in Entomology 50:1–86.

Tauber, M. J., and C. Toschi (1965) “Bionomics of Euleia fratria (Loew) (Diptera: Tephritidae). I. Life History and Mating Behavior.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 43:369–79.

Tennent, W. J. (1987) “A Note on the Apparent Lowering of Moral Standards in the Lepidoptera.” Entomologist’s Record and Journal of Variation 99:81–83.

Tilden, J. W. (1981) “Attempted Mating Between Male Monarchs.” Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 18:2.

Tompkins, L. (1989) “Homosexual Courtship in Drosophila.” MBL (Marine Biology Laboratory) Lectures in Biology (Woods Hole) 10:229–48.

Urquhart, F. (1987) The Monarch Butterfly: International Traveler. Chicago: Nelson–Hall.

———(1960) The Monarch Butterfly. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Utzeri, C., and C. Belfiore (1990) “Tandem anomali fra Odonati (Odonata).” Fragmenta Entomologica 22:271–87.

Vaias, L. J., L. M. Napolitano, and L. Tomkins (1993) “Identification of Stimuli that Mediate Experience-Dependent Modification of Homosexual Courtship in Drosphila melanogaster.” Behavior Genetics 23:91–97.

Spiders and Other Invertebrates

Abele, L. G., and S. Gilchrist (1977) “Homosexual Rape and Sexual Selection in Acanthocephalan Worms.” Science 197:81–83.

Bristowe, W. S. (1939) The Comity of Spiders. London: Ray Society.

———(1929) “The Mating Habits of Spiders with Special Reference to the Problems Surrounding Sex Dimorphism.” Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1929:309–58.

Gillespie, R. G. (1991) “Homosexual Mating Behavior in Male Doryonychus raptor (Araneae, Tetragnathi-dae).” Journal of Arachnology 19:229–30.

Jackson, R. R. (1982) “The Biology of Portia fimbriata, a Web-building Jumping Spider (Araneae, Saltici-dae) from Queensland: Intraspecific Interactions.” Journal of Zoology, London 196:295–305.

Kazmi, Q. B., and N. M. Tirmizi (1987) “An Unusual Behavior in Box Crabs (Decapoda, Brachyura, Calap-pidae).” Crustaceana 53:313–14.

Lutz, R. A., and J. R. Voight (1994) “Close Encounter in the Deep.” Nature 371:563.

Mirsky, S. (1995) “Armed and Amorous.” Wildlife Conservation 98(6):72.

Sturm, H. (1992) “Mating Behavior and Sexual Dimorphism in Promesomachilis hispanica Silvestri, 1923 (Machilidae, Archaeognatha, Insecta).” Zoologischer Anzeiger 228:60–73.

Domesticated Animals

Aronson, L. R. (1949) “Behavior Resembling Spontaneous Emissions in the Domestic Cat.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 42:226—27.

Banks, E. M. (1964) “Some Aspects of Sexual Behavior in Domestic Sheep, Ovis aries.” Behavior 23:249–79.

Beach, F. A. (1971) “Hormonal Factors Controlling the Differentiation, Development, and Display of Copulatory Behavior in the Hamster and Related Species.” In E. Tobach, L. R. Aronson, and E. Shaw, eds., The Biopsychology of Development, pp. 249–96. New York: Academic Press.

Beach, F. A., and P. Rasquin (1942) “Masculine Copulatory Behavior in Intact and Castrated Female Rats.” Endocrinology 31:393-409.

Beach, F. A., C. M. Rogers, and B. J. LeBoeuf (1968) “Coital Behavior in Dogs: Effects of Estrogen on Mounting by Females.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 66:296–307.

Blackshaw, J. K., A. W. Blackshaw, and J. J. McGlone (1997) “Buller Steer Syndrome Review.” Applied Animal Behavior Science 54:97–108.

Brockway, B. F. (1967) “Social and Experimental Influences of Nestbox- Oriented Behavior and Gonadal Activity of Female Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus Shaw).” Behavior 29:63–82.

Burley, N. (1981) “Sex Ratio Manipulation and Selection for Attractiveness.” Science 211:721–22.

Collias, N. E. (1956) “The Analysis of Socialization in Sheep and Goats.” Ecology 37:228–39.

Craig, J. V. (1981) Domestic Animal Behavior: Causes and Implications for Animal Care and Management. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Craig, W. (1909) “The Voices of Pigeons Regarded as a Means of Social Control.” American Journal of Sociology 14:86-100.

Feist, J. D., and D. R. McCullough (1976) “Behavior Patterns and Communication in Feral Horses.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 41:337– 71.

Ford, C. S., and F. A. Beach (1951) Patterns of Sexual Behavior. New York: Harper and Row.

Fuller, J. L., and E. M. DuBuis (1962) “The Behavior of Dogs.” In E. S. E. Hafez, ed., The Behavior of Domestic Animals, pp. 415–52. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Grant, E. C., and M. R. A. Chance (1958) “Rank Order in Caged Rats.” Animal Behavior 6:183–94.

Green, J. D., C. D. Clemente, and J. de Groot (1957) “Rhinencephalic Lesions and Behavior in Cats: An Analysis of the Klüver-Bucy Syndrome with Particular Reference to Normal and Abnormal Sexual Behavior.” Journal of Comparative Neurology 108:505–36.

Grubb, P. (1974) “Mating Activity and the Social Significance of Rams in a Feral Sheep Community.” In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., Behavior in Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 1, pp. 457–76. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Guhl, A. M. (1948) “Unisexual Mating in a Flock of White Leghorn Hens.” Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 5:107–11.

Hale, E. B. (1955) “Defects in Sexual Behavior as Factors Affecting Fertility in Turkeys.” Poultry Science 34:1059–67.

Hale, E. B., and M. W. Schein (1962) “The Behavior of Turkeys.” In E. S. E. Hafez, ed., The Behavior of Domestic Animals, pp. 531-64. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Hulet, C. V., G. Alexander, and E. S. E. Hafez (1975) “The Behavior of Sheep.” In E. S. E. Hafez, ed., The Behavior of Domestic Animals, 3rd ed., pp. 246–94. London: Baillière Tindall.

Hurnik, J. F., G. J. King, and H. A. Robertson (1975) “Estrous and Related Behavior in Postpartum Holstein Cows.” Applied Animal Ethology 2:55– 68.

Immelmann, K., J. P. Hailman, and J. R. Baylis (1982) “Reputed Band Attractiveness and Sex Manipulation in Zebra Finches.” Science 215:422.

Jefferies, D. J. (1967) “The Delay in Ovulation Produced by pp’-DDT and Its Possible Significance in the Field.” Ibis 109:266–72.

Kavanau, J. L. (1987) Lovebirds, Cockatiels, Budgerigars: Behavior and Evolution. Los Angeles: Science Software Systems.

Kawai, M. (1955) “The Dominance Hierarchy and Homosexual Behavior Observed in a Male Rabbit Group.” Dobutsu shinrigaku nenpo (Annual of Animal Psychology) 5:13–24.

King, J. A. (1954) “Closed Social Groups Among Domestic Dogs.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 98:327–36.

Klemm, W. R., C. J. Sherry, L. M. Schake, and R. F. Sis (1983) “Homosexual Behavior in Feedlot Steers: An Aggression Hypothesis.” Applied Animal Ethology 11:187–95.

LeBoeuf, B. J. (1967) “Interindividual Associations in Dogs.” Behavior 29:268–95.

Leyhausen, P. (1979) Cat Behavior: The Predatory and Social Behavior of Domestic and Wild Cats. New York and London: Garland STPM Press.

Masatomi, H. (1959) “Attacking Behavior in Homosexual Groups of the Bengalee, Uroloncha striata var. domestica Flower.” Journal of the Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University (Series 6) 14:234–51.

———(1957) “Pseudomale Behavior in a Female Bengalee.” Journal of the Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University (Series 6) 13:187–91.

McDonnell, S. M., and J. C. S. Haviland (1995) “Agonistic Ethogram of the Equid Bachelor Band.” Applied Animal Behavior Science 43:147–88.

Michael, R. P. (1961) “Observations Upon the Sexual Behavior of the Domestic Cat (Felis catus L.) Under Laboratory Conditions.” Behavior 18:1–24.

Morris, D. (1954) “The Reproductive Behavior of the Zebra Finch (Poephila guttata), with Special Reference to Pseudofemale Behavior and Displacement Activities.” Behavior 6:271—322.

Mykytowycz, R., and E. R. Hesterman (1975) “An Experimental Study of Aggression in Captive European Rabbits, Oryctolagus cuniculus (L.).” Behavior 52:104-23.

Mylrea, P. J., and R. G. Beilharz (1964) “The Manifestation and Detection of Oestrus in Heifers.” Animal Behavior 12:25–30.

Perkins, A., J. A. Fitzgerald, and G. E. Moss (1995) “A Comparison of LH Secretion and Brain Estradiol Receptors in Heterosexual and Homosexual Rams and Female Sheep.” Hormones and Behavior 29:31— 41.

Perkins, A., J. A. Fitzgerald, and E.O Price (1992) “Luteinizing Hormone and Testosterone Response of Sexually Active and Inactive Rams.” Journal of Animal Science 70:2086—93.

Prescott, R. G. W. (1970) “Mounting Behavior in the Female Cat.” Nature 228:1106—7.

Reinhardt, V. (1983) “Flehmen, Mounting, and Copulation Among Members of a Semi-Wild Cattle Herd.” Animal Behavior 31:641—50.

Resko, J. A., A. Perkins, C. E. Roselli, J. A. Fitzgerald, J. V.A. Choate, and F. Stormshak (1996) “Endocrine Correlates of Partner Preference in Rams.” Biology of Reproduction 55:120—26.

Rood, J. P. (1972) “Ecological and Behavioral Comparisons of Three Genera of Argentine Cavies.” Animal Behavior Monographs 5:1–83.

Rosenblatt, J. S., and T. C. Schneirla (1962) “The Behavior of Cats.” In E. S. E. Hafez, ed., The Behavior of Domestic Animals, pp. 453–88. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Schaller, G. B., and A. Laurie (1974) “Courtship Behavior of the Wild Goat.” Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 39:115–27.

Shank, C. C. (1972) “Some Aspects of Social Behavior in a Population of Feral Goats (Capra hircus L.).” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 30:488– 528.

Signoret, J. P., B. A. Baldwin, D. Fraser, and E. S. E. Hafez (1975) “The Behavior of Swine.” In E. S. E. Hafez, ed., The Behavior of Domestic Animals, 3rd ed., pp. 295–329. London: Baillière Tindall.

Tiefer, L. (1970) “Gonadal Hormones and Mating Behavior in the Adult Golden Hamster.” Hormones and Behavior 1:189–202.

van Oortmerssen, G.A. (1971) “Biological Significance, Genetics, and Evolutionary Origin of Variability in Behavior Within and Between Inbred Strains of Mice (Mus musculus).” Behavior 38:1–92.

van Vliet, J. H., and E J. C. M. van Eerdenburg (1996) “Sexual Activities and Oestrus Detection in Lactating Holstein Cows.” Applied Animal Behavior Science 50:57–69.

Vasey, P. L. (1996) Personal communication. Verberne, G., and F. Blom (1981) “Scentmarking, Dominance, and Territorial Behavior in Male Domestic Rabbits.” In K. Myers and C. D. Maclnnes, eds., Proceedings of the World Lagomorph Conference, pp. 280–90. Guelph: University of Guelph.

Whitman, C. O. (1919) The Behavior of Pigeons. Posthumous Works of C. O. Whitman, vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Young, W. C., E. W. Dempsey, and H. 1. Myers (1935) “Cyclic Reproductive Behavior in the Female Guinea Pig.” Journal of Comparative Psychology 19:313–35.