Persons and Personhood: Notes and Sketches

Annex: verb to; to add to the end: to join or attach: to take permanent possession of: to purloin, appropriate: to affix: append. – noun something added: a supplementary building. Annexe

Personal identity in general does not raise problems distinct from those concerning identity in general. The nature of a given thing determines the sort of circumstances in which it is appropriate to speak of one thing of that kind being identical with what is supposedly another.

The problems of the principle of individuation, and confronting the question of what ultimately distinguishes two things or two things of a certain kind presume certain answers to questions about the identity of those things.

‘Person’ is a forensic term, appropriating actions and their merit; and so has been thought to belong only to intelligent agents capable of law, happiness, and misery. Decisions on personal identity bring with them issues about such things as personal relations, some of them moral.

The Latin ‘persona’, especially in scholastic usage holds the primary meaning of a mask, and thereby of a role or character presented. ‘Person’ is used mostly as the singular of ‘people’. Persons can be identified with selves, or no real distinctions can be made. Thus, in speaking of a person one is speaking of a self. I am a person and so are other selves. There can be a tendency to take the concept of a person for granted and go straight to the question of the criteria of personal identity.

There is artifice about such a procedure since the term ‘person’ in these contexts is something of a ‘Person’ is in many ways a term of art, in a way that the term ‘self’ is not. The term ‘self’ reflects something about us as human beings – namely that we are self conscious and that many aspects of the forms of consciousness we have are reflexive.

Whatever a human finds they call themself, there another may say is the same person. Persons could be volunteered as social constructions – that something is a person to the extent that others so regard it. Personal identity is thus inclusively a kind of fiction, which, because of the imagination, we have a natural propensity to ascribe to ourselves, but to which nothing necessarily corresponds in reality.

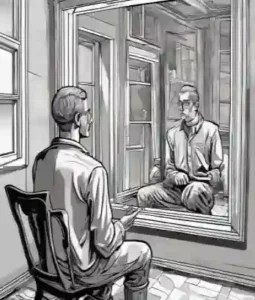

All our distinct perceptions are distinct existences and the mind might never perceive any real connection among distinct existences. What things hold good of all and only persons ? Discussion of these matters has concentrated upon the third person point of view and ignored the first person point of view. There is no such thing as a criterion of identity for oneself. The only context in which the question ‘Am I the same person as…?’ arises might be one in which one treats oneself as a third person, as one may do, for example, in looking at photographs and asking ‘Is that me ?’.

Persons, Self, and Personal Identity

If persons are nothing else, they are beings who can and do have a first person point of view. What would be the case if persons were to split or fuse ? How would one identity survive in such circumstances. Strict identity is a one-to-one relation and it does not have application where one thing becomes many, or many things become one.

Personal identity itself is a perfect identity; it is the identity of a monad and is not further analyzable. This conclusion, is derivable solely from a consideration of our own identity. When it comes to the identity of others our grounds for judgments of identity are more or less those which we rely on in arriving at judgments concerning the identity of bodies, where the identity is not perfect.

There can be found a dichotomy between first and third person approaches to personal identity. The observation of an ‘inner process’ craves a need of outward criteria. The concept of a person as un-analyzable is likely to involve a rejection of the attempt to provide necessary and sufficient conditions for personal identity on the basis of the concept itself. Elucidation of a concept need not come via an analysis of it into its constituents. It is arguable it is not possible because concepts are not isolatable entities but abstractions from a web of understanding to which they belong.

With regard to any given concept it may be possible to give only the norm for speaking of identity. One can reject the idea that the self can be regarded as a substance and therefore reject also the idea that it can be thought of as simple in the way that simple substances – monads – are supposed to be. The idea of the self is not as a simple substance. A person can be identified by their body and the body can be identified by its physical properties and spatio-temporal location, and there are certain experiences which are causally connected with it; these particular experiences can be identified as the experiences of the person whose body it is.

Can we confuse personal identity with the evidence that we have of our personal identity. One aspect of identity might be considered the connection between the concept of a person and that of the natural kind, – human, or nature or planet. The conviction which every person has of their own identity, as far back as their memory reaches, needs no aid of philosophy to strengthen it; and no philosophy can weaken it, without first producing some degree of insanity.

By person we mean a sort of animal. In thinking about ourselves and others we need to have the idea of something that owns both states of consciousness and corporeal characteristics. It is that idea which refers to the concept of a person. According to the criteria offered, animals, or some of them are persons.

People are normally referred to as belonging to the species – homo sapiens – and are therefore normally human beings. To speak of people is to say more than that they have biological classification. People think, have experiences, engage in many forms of behaviour, stand or are capable of standing in relations to other people (relations which we call ‘personal’), and in other relations to other kinds of being.

They may be the objects of ethical judgments and the subjects that make such judgments; they may be held responsible for things and be subject to appreciation and diminishment in consequence, and they may take aesthetic interests in a variety of things. To list such factors is not in itself to say what people are; however, any accounts of persons must be consistent with such factors.

Five major themes shall be explored in this work:

- Memory and Personal Identity

- Bodily Identity and Self

- Continuity and Identity

- Personal Identity and Consciousness

- Ownership of Experience

Memory and Personal Identity

The most typical identity question is backward looking, in that the form of consciousness which is directly relevant to personal identity seems to be memory. If and only if X remembers being Y or having experiences that Y had X and Y are the same person.

Memory presupposes personal identity and therefore cannot constitute it. It cannot be said to have remembered having some experience unless it is ‘I’ who had that experience. ‘I’ can think that ‘I’ remember having it without it being true; I can have putative memories without my having had the experiences in question.

A human may be, and at the same time not be, the person that did a particular action. A boy who was beaten at school for stealing matches might become a clown who took a custard pie from the queen in his first show and then become a ring master in advanced life.

The ringmaster can remember taking the custard pie but not being beaten for stealing the matches, but at the time he took the custard pie he could remember that. The ring master is the same person as the clown who took the custard pie, the clown is the same person as the boy who was beaten, but the ringmaster is not the same person as the boy who took the matches. The ringmaster is and at the same time is not, the same person with the person who was beaten at school.

We cannot apply the distinction between identity and exact similarity in the case of memories or such things as character. There is doubt on the intelligibility of speaking of exactly similar memories. To speak of the same memories would imply we were concerned with the same person, who’s memories they were.

There is no way of telling whether claims that Alex makes are the same as those made by Alan Smithee. Invoking the idea of ‘similarity of one’s supposed past’ we might say that Alex has the same character and the same supposed past as Alan Smithee but it is not to say that they are identical, only that they are similar in this respect.

Consider a person who lost all memory, and perhaps undergone a complete change of personality after some physical or mental shock, so that there is apparent discontinuity between their present and past selves. Are they the same person and/or animal as they were? The common sense answer is that they are both the same person and the same animal. This indicates the notion of animal in connection with persons and their identity.

If I am asked whether the person in front of me is the same person as one uniquely present at place A and time T, I shall not necessarily be justified in answering ‘yes’ merely because I am justified in saying that this human body is the same as that present at A and T. Identity of body is thus not a sufficient condition of personal identity.

Other considerations, of personal characteristics and memory must be invoked. While bodily identity is a criterion for personal identity, it is not the only one, and we use memory as a secondary criterion for other persons, since questions of criteria do not arise in relation to oneself. Normally it is the case that same body is sufficient for same person.

If to contemplate the possibility of that not being so, it is likely that one will also be prepared to contemplate the idea of the same body being owned by different persons at different times.

Bodily Identity and Self

The necessity of outward and observable criteria for psychological processes has led philosophers to emphasize bodily factors as criteria of personal identity. A relationship exists between the identity, of substance and of person. The identity of human presupposes identity of body.

Agnosticism may be employed as to what that substance might consist in. On the question of whether only immaterial substances can think; what is the nature of a thinking substance, and what does it’s identity consists in. The notion of a person is a largely technical concept which we need to employ and understand if we are to approach issues involved in the mind-body problem and the construct in which we think of ourselves and others.

While states of consciousness are ascribable only to, and thus only owned by minds, bodily characteristics have a similar relation to something different – the body. Are persons bodys ? Bodily identity is a necessary condition of personal identity. Persons are bodys since the identity conditions for persons presuppose those for a certain class of bodys.

That said, the concept of a person is not the same as the concept of a body. Considerations about the body are only marginally relevant to considerations about persons. All the people we know in everyday life are human beings; they all have bodies. Many characteristics would have no place if people did not have bodies. Equally they would have no place were the people in question not in some sense selves – conscious and to some extent self-conscious, beings.

The only case in which identity and exact similarity could be distinguished is that of the body – “same body” and “exactly similar body” marks a difference. We are not bound in the case of Alex, to speak of identity, only at best exact similarity, since all that we have to go on can be interpreted only in terms of their exact similarity to those of Alan Smithee. Is it possible in Alex’s case to speak of his identity with Alan Smithee ?’.

In a hypothetical future in which brain removal by surgery is possible, enabling surgeons to perform operations on the brain and then return it to the body, this happens to the subjects of Brown and Robinson, but an assistant puts the wrong brains in the wrong bodies. One of the patients then dies, and the other – to be called ‘Brownson’ – wakes up with all the memories, personality and character of brown, but with Robinson’s body apart from the brain.

In this case we can be impressed by the memories of Brown’s past life that Brownson manifests, as a criterion of personal identity. One could interpret the claim as presupposing a situation in which there is identity of body on two occasions but a person on the first occasion only, so that there is no person on the second occasion, as would be the case where a person had died in the interval.

The concept of a person is one which does not amount merely to that of a body, but to a body plus other things. Through ‘reduction to the absurd’ of the thesis, bodily identity is not necessary for personal identity. Suppose that a person – Alex – wakes up one day with all the memories (or all the supposed memories) of Alan Smithee; all his memory claims fit, as far as the evidence goes, the personality and life of Alan Smithee.

There is a temptation to say that he had become Alan Smithee, but we are not forced to that conclusion. Exactly the same thing might happen also to Alex’s brother. We trouble to say that they both become identical with Alan Smithee, or that they were identical with each other which presents to exclude the possibility that the same person might simultaneously occupy different bodies.

We trouble to speak of identity in the reduplicated case and thus we trouble to speak of identity in the case in which Alex alone is changed, for there is no bodily identity. What clearly applies to the reduplicated case cannot be transferred without further argument to the non-reduplicated one. This depends upon a distinction between identity and exact similarity, a distinction which can be made in the case of physical particulars, where spatio-temporal considerations apply.

Most claims are correct otherwise one could suggest that Brownson’s memory claims are systematically mistaken. While there is not complete bodily identity there is partial bodily identity in the brain. There is a sense in which the original person has not survived, hence there is some similarity of the position where personal identity is dependent on whatever part of the body is responsible for those mental features which go to make up a personality.

Personal identity is not bodily identity, nor strict identity of some body part but the continuance in one organized parcel of what is both necessary and sufficient for normal psychological functioning – no part being fully autonomous. The organized parcel is normally considered the brain. There are many aspects of persons as we ordinarily understand them which depend essentially on the body (for example, sense perception), which by extension can put limits upon what we can suppose of a disembodied person.

The possibility of disembodied persons having a logically secondary existence is conceivable in connection with persons who were once embodied. It might be difficult to think of ways in which intrinsically disembodied persons could be identified in practice. To suppose that this difficulty limits or removes any possibility of attaching sense to the notion of disembodied persons is to embrace verificationism. The concept of a person has been cited as simple and un-analyzable.

Continuity and Identity

The identity of a self must have something to do with the continuity of thought. The identity of a thing constitutes its unity and singleness over time. We can discover no impression of the self, or indeed anything apart from particular impressions or perceptions, each of which may exist separately in such a way that they have no need of anything to support their existence.

In ordinary language we say such things such as ‘He is not the person that he was’ and we speak of the development or growth of a person, of becoming a person, and so on. When one thinks back over one’s own past one inevitably thinks of all the changes that have taken place as changes in relation to oneself.

If there is to be personal identity must there be spatio-temporal continuity of something in the criterion of personal identity provided by the continuity of something fairly specific ? It is not clear whether spatio-temporal continuity is necessary for identity, even in the case of physical objects.

One contention holds that one ship is continuous in a spatio-temporal way with the original ship despite the change of timbers, therefore it is the original. Another contention is that the ship which is made of the original timbers is the original ship although it has no spatio-temporal continuity with the original as a ship.

Someone who replaced by stealth all the stones of the Parthenon with replicas and rebuilt the temple out of the original stones in England could scarcely expect to be declared not guilty of stealing the temple. It is possible for certain manufactured articles to be taken to pieces, reassembled into other objects (or left in pieces), and then be subject to the reverse process.

In this context the original object could be said to have a discontinuous existence, and the reassembled object which finally results could be said to be identical to the original despite not existing in the interval (although something persists). The ‘ship of Athens’ refers to the ship, with which the citizens replaced the wooden parts and built another ship from the timbers which had been replaced. The question is which of the ships is the original ship ?

There is a planet Juno in which bodies grow to maturity which are counterparts of bodies of people on Earth. When someone on Earth dies, the counterpart body on Juno comes to life with behaviour, personality, character and memories the same as those of the Earth person. The story elaborates with philosophical doubts on the part of Junonians as to whether their memories are veridical.

What would happen if communication was established between Juno and Earth. In the story there is spatial discontinuity. Were it not for the spatial considerations Juno might be an afterlife in theological conceptions. It would be right to treat certain Junonians as relatives who had previously existed on earth. There is no way, by hypothesis, of verifying the claim for identity between Junonians and their Earth counterparts.

Spatio temporal continuity is not a necessary condition of personal identity, although it is the norm against which deviations can also be seen to be intelligible, whether or not such deviations occur. Stories of bodily interchange imply spatial discontinuity, although not a temporal one. In certain contexts of personal relations, a decision of identity may be forced upon one despite everything that spatio-temporal continuity suggests.

In some estimations the sense of identity requires the existence of another by whom one is known; and a conjunction of this other person’s recognition of one’s self with self-recognition. The development of an integral sense of self is in this context contingent upon an affirming relationship with the outside world. The manner in which we are treated by the first ‘other’ in our world helps to define our own view of self, which in turn contributes to our perception of the experience of being-in-the-world.

‘What am I ?’ may be asked in a context which connects thinking with self-consciousness. The question ‘what am I’ brings with it answers to the question of the criteria of identity of oneself. Here we may explore the criterion of personal identity in consciousness. It is consciousness that makes the person, ‘self’ is that conscious thinking thing, whatever substance it be made up of, whether spiritual or material, simple or compounded, which is sensible or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so is concerned for itself, as far as that consciousness extends.

It is only on the presupposition of identity in a person that we can go on to consider what a person may be conscious of. The point has a greater reality in connection with the self than it does in connection with persons. Self consciousness presupposes an identical self. It is consciousness of personal identity that presupposes personal identity.

Consciousness, makes the same person. ‘That with which the consciousness of this present thinking thing can join itself, makes the same person, and is one self with it, and with nothing else’.

Personal identity and Consciousness

There are some philosophers, who imagine we are every moment intimately conscious of what we call our self; that we feel its existence and its continuance in existence; and are certain, beyond the evidence of a demonstration, both of its perfect identity and simplicity. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception and can never observe anything but the perception.

We could concieve of nothing but bundles or collections of perceptions and the mind as a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance. The relations that exist between the perceptions in a bundle – those of constancy, coherence and causality – make us imagine that there is such identity and simplicity. Every perception, every intuition must be brought under concepts in judgment, as an exercise, not only in consciousness, but also in self consciousness.

In doing this I must be aware, at least in principle, that the representations that I have and the judgments that I make are mine. Perceptions cannot exist un-owned or be in any way neutral as to whose they are. The ‘I’ is therefore presupposed in the very having of a perception, so that consciousness with respect to perceptions is by the deed itself self-consciousness with respect to the ‘I’.

‘I think’ has the ability to accompany all our representations. It also has the ability to accompany all our behaviour. The concept of pain is constituted by forms of behaviour which are natural expressions of pain. Behaviour constitutes the criterion which is referential to the self and person, not just any bodily characteristic.

Accompanying this, the criteria for the concept of person as necessarily being a part of behaviour. Thus anything that does behave must either be conscious or potentially so. The criterion of personal identity lay in the identity of consciousness, in so far as we are concerned with the attribution of responsibility, and that looking to the past, consciousness amounts to memory.

Can we legitimately be held responsible only for what we can remember ? A person is a self which has self consciousness at least to the extent that they are conscious of their past as their own. Are one’s states of consciousness ascribable to anything at all ? Why are one’s states of consciousness ascribed to the very same thing as certain corporeal characteristics, a certain physical situation ?

To the extent that they are ascribed to the same thing it is because states of consciousness are expressed in behaviour for which a body with corporeal characteristics is necessary. Must persons be embodied ? To make sense of the idea of a disembodied person, we are talking of something that still has or ‘owns’ states of consciousness.

In the case of a dead person it is difficult to think of anything but the corporeal characteristics that remain. Anything with a legal responsibility and status, such as a company, might be counted as a person. Responsibility, rewards and punishments attach to a being only in so far as it can be thought to be a person, and that only in so far as it has consciousness of what it is held responsible for. Decisions about the identity of a person follow from decisions about what we can hold responsible for what.

The experiences which are mine are those to which my consciousness can reach. The identity of a person is proportionate with the extent to which their consciousness reaches. ‘I’ implies an essentially first person point of view in our approach to the issues. It is reasonable to expect that there should be some connection between this and third person view of issues.

There is an argument that consciousness of personal identity presupposes, and therefore cannot constitute personal identity any more than knowledge, in any other case, can constitute truth, which it presupposes. The identity of a person is a perfect identity; wherever it is real, it admits of no degree because a person is a monad, and is not divisible into parts.

Questions about responsibility arise only when questions about identity have been answered and not vice versa. Application of the concept of a person brings with it the applicability of concepts having to do with responsibility and its consequences as regards reward and punishment.

Ownership of Experience

Questions arise from a consideration of the ways in which we talk of ourselves. Every perception, every intuition must be brought under concepts in judgment, as an exercise, not only in consciousness, but also in self-consciousness. In doing this I must be aware, that the representations that I have and the judgments that I make are mine. Perceptions cannot exist un-owned or be in any way neutral as to whose they are – ‘I think’ can accompany all our representations.

The ‘I’ is therefore presupposed in the having of a perception, so that consciousness is by the deed itself self-consciousness with respect to the ‘I’. States of consciousness do not belong to anything, although they may be causally dependent on the body.

One perspective holds that states of consciousness must be ascribed to something, and that something must have physical characteristics also. It is not reducible either to something mental or to something physical, as it is presupposed by both. States of consciousness which take place are causally dependent on the states of the body.

All that there is to the thought of states of consciousness being owned is their belonging to such things. That is all there is to the thought that they are had by or owned by anything. In other words, the identification of experiences depends on the identification of their owner; experiences must be owned.

One might argue that there are two issues at stake here, one of identification of experiences and one of the nature of experiences. Experiences owe their identity as particulars to their owners. It is possible to identify experiences in ways other than by reference to their owner, for example, by reference to some particular quality they have.

How might one state the relationship between certain experiences and a certain body in a way without invoking the owner of the experiences ? If my body is in such and such a state, then an experience of such and such a kind results; if an experience is causally dependent in this way on the state of my body, then the experience is mine.

There are certain experiences causally connected with any given body; i.e. those which are owned by the person whose body it is. There may also be other experiences which are owned by others which are also causally connected with that same body. Other people’s experiences may be causally connected with the state of my body.

Here it can be conceived of that there is no way to distinguish among the experiences that are causally dependent on the state of my body in regards to whose they are. In this context, experiences trouble to be neutral as far as their ownership is concerned. If I ascribe states of consciousness to myself, it must make sense to speak of ascribing them to others.

It follows I can ascribe states of consciousness to myself only if I can ascribe them to others and I can ascribe them to others only if I can identify other subjects of experience. Here employed is the idea that there is, both in our thought about ourselves and in our thought about others, a reference to something which owns both states of consciousness and bodily characteristics, and which thus constitutes a distinct category ‘person’.

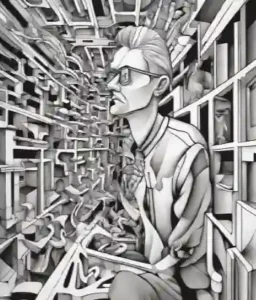

In those cases where states of consciousness are ascribed to the same thing as corporeal characteristics, the thing that owns the states of consciousness, the self or ‘I’ in question, may be embodied and normally is so. Being prepared to ascribe states of consciousness to others is possibly the intellectual ground whereby we start the understanding of the individual and and beginnings of a portrait.

If I ascribe states of consciousness to myself it must be possible for other ascriptions to be made. It is from these ascriptions that one might perceive the necessary identities and comparisons needed to, in some meaningful way, exaggerate the idea in mind we refer to as a portrait.

The Language of Personal Identity

In conclusion of this exploration of person, self and identity it might be most apt to visit the language at its lexical origin. What is contained in these words is an indicator of what is being invoked when they are use.

Person is the noun used to express a ‘character represented, as on the stage; a capacity in which one is acting; a living soul or self-conscious being; a personality; a human being; an individual of a compound or colonial animal; the outward appearance; bodily form; human figure (often including clothes); bodily presence or action; a personage; a hypostasis of the Godhead; a human being (natural person) or a corporation (artificial person) regarded as having rights and duties under the law.

A form of inflexion or use of a word according as it, or its subject, represents the person, persons, thing, or things speaking (first person), spoken to (second), or spoken about (third). Jung used it’s Latin form ‘persona’ meaning a players mask (or possibly from Etruscan phersu for masked figures associated with personare, atum, -per, sonare, meaning to sound. By Jung’s usage it is the term for a person’s system of adaptation to, or manner assumed when dealing with the world – the outer most part of consciousness, the expression of the personality.

Self is the Old English pronoun used as oneself, myself, himself etc: a side of ones personality: identity: personality: what one is : self interest: self-coloured plant or animal: a thing (especially a bow) made in one piece. ‘I’, the pronoun, is the nominative singular of the first personal pronoun: the word used in mentioning oneself.

The noun, the object of self-consciousness, the ego from ME. ich; Old English ic; Ger. ich; O. N. ek; Latin, ego; Greek ego. I, the ninth letter of the Latin alphabet, answer to Greek iota, the smallest letter in the alphabet. In Roman numerals represents one. In mathematics ‘i’ represents the imaginary square root of minus one (-1).

The word animal is a noun which describes an organized being having life, sensation and voluntary motion – typically distinguished from a plant. Animal spirits formerly refereed to a supposed principle formed to all parts of the body through the nerves, nervous force, exuberance of health and life; cheerful buoyancy of temper: the spirit or principle of volition and sensation according to Milton.

Perhaps the Latin root of the word animal; anima might add further meaning in this context. Anima means air, breath, life and soul.16 Portraits and Portraiture What immediately comes to mind in contemplating portraits of people is what do we perceive of in other people and what do we perceive of those moments between one motion and another, between one conversation and another, one statement and another ?

In some ways this is where I feel people’s self resides alike to the perfect platonic solid being perceived in the casual circle one comes across. When animate in a particular expression we are acting out a particular essence which only seems non-coherent with time as a framework….

At this moment, at this point, I felt like this and the expression of the sum of my experience was such and such. A poetic way of conveying this might be how each note, riff, composition and orchestration emerges from silence, the whole, and gives form to that particular moment in time, the perceived fourth dimension, as it is emergent, superseded, and diminished.

The silence underpins the music and is the stuff of which it is necessarily made. The task which the portrait maker takes on is in some ways to defy the parameters of the medium, and by utility of illusion create an impression which leads to a feeling akin to knowing; possibly the same tool of artifice which we, as sentient beings, use every day to express with and interact of the universe. What we see in other people is many a multitude of things.

It is through knowledge of one’s own self that we can identify with what we are experiencing. This birth of a particular thread of intellectual consciousness is found in the expression ‘theory of mind’; that faculty which informs us that what we are directly experiencing is not necessarily that which others are also experiencing – possibly theory of mind represents the birth of the syllogism…?

From this perspective we might consider what occurs as a strange thought; just how much do we create other people, and in its reciprocal, just how much do other people create us (one’s self). From experience there are a many phrases which reveal our heuristic assumption ofothers through speech, i.e. “I always thought that you…”

Through my cumulative experience I have come to understand that a starting point of experience is the projection of the subjective unto the world situation I encounter before an iterative process of syllogistic analysis to arrive at a ‘truer’ articulation of what transcends my sensory apparatus. By extension I develop my understanding of those I experience and I refine the heuristic process by which I encounter the universe and souls I meet.

This line of thinking it is relative of how much we might know of others or develop and cultivate knowledge of one’s self. A kind of Socratic problem is arrived at: Who is to judge a portrait and what criteria apply ? From one perspective one could say that only the subject might judge a portrait, from another, one could perceive the artist as a trained observer being a good candidate to judge a portrait.

This only indicates two points of reference in a spectrum. The Socratic problem refers to the fact that due to the various conflicting accounts of Socrates we are left asking which, if any, are accurate representations of the historical Socrates.

All those who knew and wrote about Socrates lived before any standardization of modern categories or sensibilities about, what constitutes historical accuracy or poetic licence. Mixed with all this is the fact that all authors present their own interpretations of the personalities and lives of their characters, whether they mean to or not.

Suffice to say that to some extent we create mental accounts of others in our ‘own image’ before making adjustments through discovery of obviated difference. Assumption in this circumstance might seem part of a necessary tool, and assertion of assumptions might be the mechanism by which we might obviate any difference.

How much we are created by others is a reciprocal consideration in this contemplative line. Portraits must attempt to be as deep and as rich as those who are the subject of a work of portraiture. In this sense the artist must surely attempt to be a receptive medium mindful and insightful of its host. What notions we commit to paper in creating a portrait are numerous.

Perhaps it is the intent of the author which is the final lens through which the portrait will is passed in its creation. Motive is key in giving bearing and direction to the authors intent. The returning questions of who might be best to judge or know a portrait – the sitter or the artisan – are some of the inexhaustible curiosities of portraits and perhaps represent something of our fascination with them.

The portrait has natural intrigue, an indirect or underhand scheming or plot: a private scheme: the plot of a play or romance: a secret illicit love affair. A portrait has natural intrigue as there is a person in it. Where there is a person, there is intrigue. The many questions of who we are, and, who we are looking at and witnessing naturally accompany the portrait.

When we look at a portrait these ideas are always invoked ? A portrait reveals something about the nature of the sitter. A portrait is a representation of a person or an aspect of the person which is integral to the defining character of the individual. Does the portrait have to be recognizable as a representation of the person ? By definition, yes.

Without identity, or some form of identification, it is hard to conceive of a scheme whereby we may apply the term portrait to the art in reference to the subject. By lacking or removing the reference to a person or self the term portrait is no longer applicable.

The process of making a portrait or sitting for a portrait has for many curiosities, fears and anticipations. Being the subject of a portrait creates the situation one is being observed and is the subject of some form of scrutiny. How we individually meet this scrutiny depends on a great deal of things, including the manner and technique of the artist. All these themes add depth and complexity to the portrait as a medium.

We could conceive of a scheme whereby a portrait may be placed on a line which has abstraction at one end and realism at the other. An abstract portrait might refer to a work of which only the sitter could identify the work as a portrait, but whereby someone who intimately knows the sitter does not.

A portrait at the realism end of the scheme might refer to a photorealistic image that any given person might identify as the sitter though there may be many more things revealed in a single image than physical identify alone. For these purposes it is suffice. Various successive points on this plane of identity between abstraction and realism might yield portraits with varying levels of anonymity. Where say, the sitter and those close to the sitter recognize the work as a good representation of themselves and the sitter respectively.

Memory and Personal Identity Some kind of representation of the history of the person, of time and accumulation and the individuals trapping of these. Seminal moments of which the sitter cites. Day to day routine, habits and habitats. Go through old photographs they might have.

Bodily Identity and Self

Create portraiture which in part comprises the bodily identity contextualized by representations of the non physical elements which go towards comprising identity. A study of their body and its unique features/figures. Reflections on their attitude to bodily identity. Discussion of what the sitter perceives themselves as.

Continuity and Identity

Explore the nature of change and belongings and history with the sitter. Retrospective and dialectical representations. What they see as permanent. As they have changed, how have they come to see their changing identity. Changing perceptions through periods of proselytism.

Personal Identity and Consciousness

A series of seminal points/moments/artefacts of the sitter might be brought together to give character and themes to the work without turning the act of making a portrait into a psychoanalytic enterprise. Mirrors and inflections.

Ownership of Experience

By perceiving the making of a portrait as a co-operative process which is steered by both the artist and the sitter, the ownership of the experience should manifest in the art. In a manner, the artist might be idealised in a passive reflective role to the sitter, as one would find a mirror in relation to a subject.

Further Reading:

Julian Edge – Cooperative Development

Carl Rogers – active, reflexive listening

Ann Cahill – Derivatization

The pragmatic between the ideal and the utilitarian

Duty of Candour –

Ken Doka – Disenfranchised Grief

Human Rights Based Approach

Structural Violence

The corporate parent as person at centre

Kruger-Dunning; institutional corruption;