The Real Story of Recycling, Waste and the Environment: International Waste Management – Crisis And Opportunity

The following learning resource is based on the transcript of the above audio recording of a presentation given by David Brown who has worked for Derbyshire County Council.

Table of Contents

Personal experience in waste management

I’ve been involved in waste management for about 20 years. Very much at the coal face, through a mixture of professional incompetence and good luck, I’m still very much at the coal face trying to stay on that level. Over the 20 years that I’ve actually been working in this field, I have had lots of experiences. I started off with the environment agency, and that involved a lot of work looking at the enforcement side of waste regulation.

That was up in Lancashire, and that allowed me to have some wonderful experiences, actually seeing the end result of how we live our lives in this country and around the world increasingly, and actually getting to grips with the scale of the waste management issues and the scale of waste disposal.

Inspections and realizations

As part of that job, I inspected waste management facilities to try and encourage them to be run in the proper way and to encourage compliance with the Environmental Protection Act. That meant that I was inspecting landfill sites as well and seeing the vast scale of waste disposal. I would go to sites such as the Whinney Hill site up near Accrington, and I would walk across it and check that cover was being applied and that the waste wasn’t escaping the site. Just to give you a scale, you know, I could walk about this speed for 45 minutes, and I’d still be on the landfill site, and I’d still be looking down, potentially, literally at a mountain of rubbish.

Memorable incidents

So what you get is like a cliff at the edge of the cell that’s being developed, and this gave me some wonderful experiences. One of my first ones was falling into a sewage sludge trench. Back in those days, the early ’90s, the idea of health and safety hadn’t really dawned on landfill managers. I was making my way on a late November day, probably just me and the driver left on site, and I was carrying my gas machine because we used to measure the landfill gas.

On the side of the site, I came across an area which I basically just didn’t notice, but apparently there were a few highly visible warning tires around this trench. I thought it was a great way to warn me of a trench to have some dirty tires on a dirty floor. So, of course, I carried straight on into this thing. Thankfully though, I wouldn’t be here today, if I hadn’t fallen backwards. I sort of fell backwards, and I was able to lean back onto the soft ground because underneath it was about 30 feet of sewage sludge. The driver on the side managed to come and dig me out underneath the armpits and dragged me out; the stench was quite remarkable, actually, even by my standards, which were pretty bad anyway.

Then I drove back to Preston at the start of winter with the windows fully down. I had to basically take my clothes off before I got in the house and then leg it into the house and try to get these highly hazardous clothes into the dustbin. But that was one opportunity. I also got to meet people like scrap yard operators (some of my favourite characters). In a bizarre sort of way were in east Lancashire, there were scrap men there who never quite knew what they were thinking. They were often actually very, very intelligent and switched on and ran rings around me most of the time, actually.

Encounters with unique characters

I made the foolish mistake, unlike most environment agency officers, of actually trying to implement the law and drive change, which didn’t go down too well. But there was one character, a legend in my mind still, he was called Dirty Billy. There were just so many different reasons he could have been called Dirty Billy. He was really an extraordinary character—the sort of chap you see with a couple of hundred quid in his hand. Ironically, the last time we ever saw him was when he was in court as we prosecuted him.

He ran a scrap yard with their vehicles 15 to 20 cars high and it still probably exists like this. Back in the late ’90s, I always wondered and dreaded to myself what would happen if one of these things caught fire. One day it did, and it was basically like a small atom bomb that went off in east Lancashire. Smoke—I remember this—I came off an inspection, and I looked east and saw this vast black cloud rising into the sky, miles into the sky. I was thinking, “oh my god, please no, don’t let that be one of my sites.” But it was.

www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-lancashire-38233493

The ramifications of poor waste management

So this night was east of Blackburn, and 20 miles west of it, 25 miles west, in Blackpool they could see the smoke. The M65 had to be closed, and it was quite radical. More recently, there were also landfill site owners who were very interesting characters—the full range, full spectrum of people—back in the late ’90s who were running major landfill sites.

There was one chap who was charming, but he was also a cowboy, and he was insisting to me that he had this wonderful bioreactor going on in this landfill site and that it was imperative to not cover the waste because you needed to let the water in so that it could break down quickly. He suggested we could get rid of the waste really quickly by basically not doing all the things that the environment agency wanted him to do.

Engaging the public and changing habits

More recently, I’ve moved over to looking at talking to and engaging with the public and trying to influence and encourage people to change their habits and to make changes. The issues are simple but there’s a lot of levels of complexity – there is the level of impact globally.

It’s been a great experience to talk to so many people across Derbyshire, trying to get to grips with why they recycle or why they don’t recycle, what they think, and trying to control the conversations, which often start on the right foot of “do you recycle your plastic?”, “what sort of plastics do you recycle?”, but then so often, quickly get moved on to people’s conspiracies and things like that. I’m trying to keep a straight face—yes, yes.

Introduction to international waste management

So tonight, I’m talking about international waste management. I’m just trying to give an overview and tell a story about what’s happening out there in the world. We’ve got some really good news happening in the UK and England about changes that have been made. Amazingly, if we all did some very simple actions, we would make a drastic difference.

The problem is that so many people aren’t making those changes, and that’s something we’re continually cracking and grappling with, trying to help people make that change and crucially to thank them for the efforts that they’ve made already because there are a lot of people out there who are completely dispirited about the situation.

Case study: Waste crisis in Lebanon

They think it’s pointless, and they don’t realize that their efforts are actually making a big contribution. Just introducing the waste crisis, Lebanon. This was Lebanon in 2009, and this is in the city of Sidon, called the Saeed landfill along the edge of the Mediterranean. Across Lebanon, there are about 700 illegal and unsafe waste dumps. There are only 10 waste recycling sites in Lebanon as of 2012, with 40% of the waste going into dumps. In this talk, what we’re talking about in terms of dumps is the totally uncontrolled dumping of material into big mounds, basically.

In England, in the UK, when we talk about sites, they have increasingly become highly engineered, highly sophisticated places with permits governing how they operate. You might have 50 or 60 different conditions that they have to comply with. In much of the world, nothing of the sort exists. It is literally, as you might imagine, dumping into the environment—totally uncontrolled.

Historical context of waste management in Lebanon

This started in 1982 after the war with Israel. It was initially used as an area for disposing of the buildings that had been destroyed in the war with Israel, but once it became established, it was then easy for other soldiers, businesses, and commerce to add their own different domestic streams of waste to it. It grew and grew to a spectacular and disastrous size. There were reports that at one point, you had 150 avalanches of waste falling into the sea. Not surprisingly, it was thought that swimming in the area, if you were crazy enough to do that, could lead to hospitalization. Some people maybe were forced to work in and around that environment.

Economic impact of waste mismanagement

They’ve estimated that Lebanon was losing 500 million dollars annually to the pollution, ill health, and agricultural losses associated with that. But now I have looked into it, and apparently there has been an improvement there just in the last two or three years. And actually, there are a few case studies that I picked out, and it was quite pleasing to see that literally just in the last two or three years, perhaps because of the scale of the crisis they were facing, action has been taken—sometimes quite chaotic action but better than what was there before.

Progressive measures in Lebanon

Here, what they did was develop a sea wall. They decided to close the site off to do any further waste deliveries, and then they transported a lot of the material to a processing facility. Now, the sceptics say that a lot of it just went into other landfills, but at least it wasn’t into the sea. There was an accusation that when they built the sea wall, the breakwater, they actually used some of that material to do that with. So in that case, it would still be going to the depths of the ocean.

Some of this material had been turning up in Cyprus, but I don’t know how you could know that because materials washing up in Cyprus could have come from Italy or anywhere in the Mediterranean basin. That’s one example. They’ve actually tried to get plans to make it into a green park—basically remove it, that amount of material, and replace it with a parkland area. However, to do that, you’re always going to have some of the waste underneath that material, I think, but at least that is positive.

Waste management challenges in Italy

But it’s not just in developing or poor countries that they have this problem. Not all this is Italy, and the area around Naples you may know has tremendous problems with poor waste management. There are frequent crises. Basically, two or three years ago there was a crisis when the landfill space ran out completely. They couldn’t find another outlet for it, and it just built up on the streets and was burned on the streets and in the countryside. That sort of crisis seems to ebb and flow, come and go, and I think they’re on top of it more recently, but only by shipping materials up to Holland.

All through that, you’ve had a much more dangerous criminal operation—mafia-type operations of fly tipping in the Campania region—with dumping of hazardous toxic domestic and industrial materials, potentially linked to things like cancer, allergies, and birth defects. There’s a vast amount of illegal and hazardous waste which has periodically been set alight, and the locals have great concerns. Some of the farming locals are concerned that the materials and rainwater will go into aquifers and then be taken by agricultural crops, and then end up back in the food chain.

Illegal waste dumping and its impacts

Ten million tons of waste material was dumped in that zone between ’91 and 2013. Just to give you an idea, 10 million tons is about a third of the total household waste production in the UK each year. So it’s such a small area – that’s a heck of a lot of fly-tipped material – but of course, it’s a massively lucrative business as the cost of disposing of waste properly goes up.

It becomes massively lucrative for criminal gangs to sort things out and for businesses to avoid proper waste management legislation. Unfortunately, locals pay the price. There will be all sorts of other costs like that. It’s not going to be looking great on the tourist cards and brochures.

Innovative solutions in Bangalore

Another example is Bangalore, where, again, until last night actually, I didn’t realize there was good news in Bangalore as well. They seem to have a pattern—you get to this point of absolute crisis, and then you react, but you’re really late, which makes things actually worse. But then you improve things drastically. That tends to be human nature, and I think it might be happening in Bangalore where they have enormous dumps on the streets, and obviously, their transmission vectors for disease and pathogens are very detrimental to people in the economy.

It’s estimated that the city is producing about 5,000 tons a day of waste, 1,500 tons of which is plastic. Only 25% is recycled, but actually, 25% recycling is as high as some of the very worst performers in the UK; I just found out that a local businessman called Ahmed khan has taken on this, in the absence of concerted municipal action. He’s taken on the opportunity to create what he wants to call a “society of eternal waste scarcity.”

He’s looking to use the plastic to—he’s in fact using the plastic already to make roads—and he’s gradually getting recognition from the municipal authorities. He reckons that they could lay 500 kilometres worth of new road each year by using some of the plastics that are coming out of the Bangalore waste stream. He’s gradually getting recognition from Bangalore, Calcutta, and Delhi that this might be a good option. So let’s wish him good luck because I think you need some spirited individuals fighting the corner and business people and innovators to tackle this crisis. Sometimes the governments, the municipal authorities, are just overwhelmed, under-resourced, and under-financed.

Current waste management issues in the UK

Once they see an option that can cut their costs, then they might jump on it and match funding or reinforce what he’s trying to do. But it’s not just abroad; this is the extraordinary scene in Essex in January—a mile long. So it made the BBC news, and it gave some insight into the crisis in the UK because there is a crisis in the UK. I’m sure if I’d been able to see out of the train windows tonight I’d have seen all the waste piled up on the embankment.

You don’t have to go far to see it. The environment agency expects to take action against 11 people or businesses on this crime, and clean-up cost is expected to be around £100,000. It’s estimated that the total cost of fly-tipping in England last year was about £808 million. Interestingly, for every £1 spent on enforcement and prevention action, the economy recovers over £3.

So if you spend—unfortunately this is in the direct opposite direction to where we’re going—but if you spend £25,000 employing an enforcement officer to look into this, you’ll get more money backing waste prevention and prevention of crime and setting examples of prosecutions so that we’re all less inclined to do this.

The economics of enforcement and prevention

At the moment, I think they believe they’ve got almost a blank check because the regulatory structure is being challenged and the resources are being undermined. By reducing fly-tipping in the first place, you then reduce your clean-up costs. You actually have more tax because all of this issue and all this material should have been taxed under landfill tax if it would have gone into the waste stream or alternatively if it had gone through recycling or reuse, it would have contributed to a thriving economic sector—a legitimate waste sector.

Last year, there were around 3,000 investigations into fly-tipping just to give you an idea of the scale, the impacts are enormous.

Understanding the global waste crisis

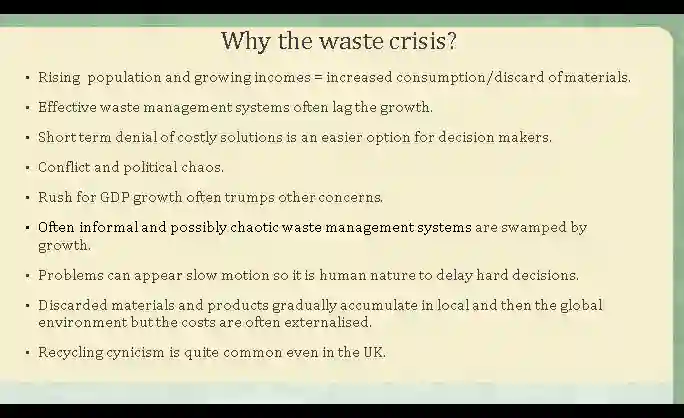

Why the waste crisis is occurring ? Essentially, across the world as a whole, as you probably know, we have a rising population and rising incomes, and that means more waste; it means more consumption of materials; it means more stuff. Because what happens to that stuff is the crucial thing one of the points about the rising population actually is that there’s a tendency for urban populations to produce a lot more waste than rural populations.

It’s worth reflecting that by 2050 there will be as many people in urban environments as there were on the entire planet in the year 2000. So that shows you the potential for growth. Also, municipal solid waste is basically a term that refers to waste in this country that’s collected by the council and a bit of additional commercial waste that the council might choose to collect. So it’s basically household waste, and that’s expected to nearly double from 1.3 to just under 2.4 billion tons between 2010 and 2025.

The cycle of consumption and waste management crisis responses

As we find, as in Bangalore, affected waste management systems lack growth. There’s a frenzy of consumption, and everyone starts drinking coca-cola or using plastic and getting electrical toys, and then a few years later they realize there’s a crisis, and the authorities wake up to that and then have to react in a panicked way. Human decisions and human decision-making are always easier to deny the problem, especially when the problem is going to be expensive to tackle. It’s going to require resources, investment, time, and public commitment.

External conflicts and waste management

We always want to put off difficult, costly decisions. There’s conflict and political chaos —waste management might not be the top priority in Ukraine or possible eastern Ukraine at the moment—but these will eventually have massive impacts on the environment. A country in chaos is unlikely to have an effective waste management system being developed necessarily. I don’t know Ukraine’s waste management; it might be perfect.

There’s a natural tendency for governments relating back to the sort of neoliberal concerns to trump the wider societal concerns, so we have the rush for GDP growth ahead of anything else. That’s clear from most of what politicians say and do. The prospect of knocking half a percent off of GDP for any reason is just almost unthinkable. That always comes first, and we’ll deal with all the side effects later.

The challenges of informal waste management systems

In a lot of the world, you have informal, chaotic waste management systems that are swamped by the growth. Quite often, there are very informal systems which maybe were effective before the big boost in consumption and growth—literally people taking materials from castles or maybe taking it off landfill sites themselves. There are communities online for facts that do that, but as well as all the social issues involved in that, they’re not able to recover adequate amounts of material once growth takes off.

The illusion of waste disappearance

So the problems can appear in slow motion with a bit of waste on the ground here and there, building up. People start to turn a blind eye to it because it’s a difficult thing to think about; before you know it, you have mounting life in Lebanon and real crisis scenarios developing for the environment. The other thing about waste is this idea that it’s going to go somewhere else; it just magically vanishes; it’s going to end up somewhere; the costs are externalized. The cost of me throwing the wrapper on the floor—well, it’s not going to bother me; if I knew about it, they might affect a fish in the pacific 30 years later, so what’s the problem with that?

The long-term consequences of mismanaged waste

The costs are externalized, but as we know, they gradually come back to haunt us over time. Another big issue in the UK actually is we have to work really hard, and a lot of people think that their recycling is not recycled, and they think it all goes into the same bin anyway. It’s insane to think that all their efforts are pointless. Councils do spend a lot of time trying to convince the public and get the message out. A colleague of mine spent the last six months trying to trace where exactly all the materials from Derbyshire county council waste collection teams actually end up, and where they actually go.

Building public trust in waste management

We’re going to do quite an extensive campaign called “what happens to your recycling?” Because the research shows that that’s the single biggest parameter that might change behavioural attitudes on waste. For a lot of people, it is to know what really happens to the materials because they don’t know, so we need confidence and reassurance on that.

Similar project:

Environmental impacts of waste

The impacts of the crisis can lead to flooding. Ironically, tonight there has been some flooding in the Bradbury East Manchester area—maybe a mixture of blocked drains from waste and inclement climate change-induced weather. Waste makes a 4% contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, with landfills and the degradation of organic matter making a significant contribution to methane emissions, which is 21 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

Information source – The UNFCCC secretariat (UN Climate Change) is the United Nations entity tasked with supporting the global response to the threat of climate change:

unfccc.int/news/a-new-plastics-economy-is-needed-to-protect-the-climate

Wastage, resource usage and climate change

The 4% contribution will come about partly because of the waste of resources and the need to use more natural resources once your original resource has been wasted. For every ton of stuff made, several tons are generally wasted. If we can drive reuse and waste prevention, that makes an enormous impact. Recycling is great but makes a lesser impact. We’ve got lots of valuable land space, which is more of an issue in some countries than ours. Japan has the highest incineration rate, but that may be possibly because of the tightness of land.

The global waste crisis

This is also a big issue in this country with soaring land price values. You have the unquantified but potentially massive effects on the ocean. There have been some good articles on that just recently. It’s calculated that something like 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic are in the sea, weighing about 260,000 tons of momentum, with the big gyres of plastic in the central oceans of the Indian ocean in the north and south pacific. I haven’t quite worked out how this works, but apparently, a researcher this year has found that in one part of the central pacific, you could actually get out and walk on this stuff, which you can only think is a thick enough mat on the ocean of stuff.

Apparently, some of the highest concentrations you might be looking at show 800 water bottles in the sea for every square kilometre. I was astonished and disturbed to learn that only in 2012, only 9% of us plastic was recycled, which is a shocking level in the united states. There are obviously big issues there, and what they’re finding is that there’s been balance between what they expected to find in the ocean in terms of plastic; it doesn’t add up. The amount that we’re producing is going up; the amount that’s entering the sea has been going up dramatically, but it hasn’t appeared at the surface, so things weren’t adding up; they were wondering what was happening.

Information source – National Geographic

Plastic pollution in our oceans

But actually, what they now seem to be saying is that a lot of plastic is breaking down in sunlight in the sea more quickly than they thought, and you’re getting tiny fragments of plastic accumulating in the water column and then on the sediments of the ocean as well. Those materials are also being colonized by potentially pathogenic bacteria, which can then get into the fish. As those plastics then break down, you have the release of additives, toxic retardants, etc., into the fish.

There’s thought that if you regularly eat shellfish in Belgium, now you’re exposed to 11,000 pieces of microplastics per year. And we’ve also got these new products – there are cleansing products, which are a new one to me as well, that contain these microbeads of plastic, which just go straight through the water system, the water treatment works, and out into the ocean. So, one thing we can all do is make sure that our products don’t contain those microbeads.

Information source – Open access peer reviewed paper

Water and the old dilute and pollute philosophy

In addition, waste results in the pollution of groundwater, surface water, and drinking water. That’s why we now have very highly engineered landfill sites in the UK, and that’s what has pushed the cost of landfill dramatically. One of the things is that to even consider having a landfill now – the level of engineering is really, really almost prohibitively expensive, which is good news.

I think, of course, in much of the world, we’re still on the system that we used to be on, which was the old dilute and pollute philosophy. That was literally a philosophy when it started in waste management: that if you dilute it enough, it’ll be alright, which is why we allow ocean dumping and things like that. Just put it in a big enough depository and don’t worry about it.

Stealing from the future

Waste is basically the theft of resources from the future. And that’s one thing that disturbs me about the whole environmental topic, is what people do think about the future, but often they think it’s hundreds of years away. I would argue, no; it really is our lives that will be affected, not just children’s lives – our lives. This thing is happening really rapidly, so we’re still stealing resources from ourselves by wasting them, which will eventually feed back into the economy.

Economic implications of waste

Since 2008, that was linked to banks and all sorts of issues there, but essentially, you’re starting to see a much more volatile commodities market. And of course, there’s a moral case of a shameful legacy from all this waste. Just in terms of the commodities you see, that oil price trend is not necessarily adjusted for inflation, so it is a bit exaggerated. You can see that the real rate of oil prices began to rise in just up to 2000, which is basically when demand started to hit supply levels. Since then, arguably, that enormous fight there – well, it probably did impact on the global economy and contribute to the massive recession that then followed.

I remember after that recession, sort of in 2009-10, the thought was that oil prices would stay at 30 dollars a barrel for the next five to ten years, but actually, within a few months, they were shooting back up, and they then had a very, very protracted period along a hundred dollars a barrel, which has stimulated all sorts of exploration and the shale gas exploration.

Information source – book chapter

link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10258-023-00237-2

Save oil by preventing waste

The real interesting thing now is that because of all that, because of those very high prices and because of the extra supply, prices have now fallen… But the rig count for U.S. oil rigs has already dropped by a third in response to that change, so the baseline price of oil production is probably somewhere up there at the 80-dollar barrel level. A lot of the current oil production will come off stream pretty quickly at the price that we have now. Recycling is a fantastic way of saving oil, and waste prevention is even better.

Understanding waste projections

So, this just shows the overall waste projection with different scenarios. This is the baseline scenario; that’s the scenario we take concise action on, and that’s our worst-case scenario for just always growth. This is really interesting, and one of the things that really struck me during the preparation this time – it always strikes me, but it’s just how important we still are, actually, as consumers, and we are relatively, disproportionately large wasters of materials and users of stuff. So, we have a massive influence on the overall impact.

Information source – What A Waste: A Global Review Of Solid Waste Management; World Bank

So, 44% of total waste is still coming from OECD countries, even though, you know, that’s not by far the biggest; the Chinese population is in this bit here. The whole Middle East and North Africa is contributing 6%, that’s South Asia including India. There’s a huge population, but a much smaller contribution to total waste. Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), I think, right? Oh, right…

Comparative waste generation

I mean, if you think of rich western countries – western Europe, the united states, Canada, Australia – that’s probably, just in case there’s one best way of thinking about it. Waste generation factor is four times higher in Canada and the united states than in many African countries.

So, that’s waste per capita; you get a picture from that. Today urban India produces just a little more waste than urban Britain Of course, the urban Indian population is about 300 million, whereas we are 50 million people, but we’re still producing just almost as much waste.

Even by 2025, U.S. waste production will still be almost double that of India’s, despite having a population of 320 million as opposed to 1.4 billion. There’s the massive growth of China, and that does mean that in total, China might produce twice as much waste as the U.S. by 2025. But per person, it will still only be a third.

Financial implications of waste management

The cost of managing waste globally is lifted at 375 billion pounds. Absolutely, Oxfam says a much smaller figure than that would be enough to end extreme poverty the world over. And in many countries, actually, municipal authorities’ waste management is the biggest budget item.

Global waste management strategies

This is, interesting as well; it shows the total global waste and what happens to it. So, we’ve still got, by far, the biggest proportion going into landfill or uncontrolled landfill with dumps. We’ve got a growing recycling rate, which is growing slowly. We’ve got,also growing waste-to-energy, which in previous years has been called incineration, but it’s definitely waste to energy in the UK now, so very highly controlled plants which deliver energy from heating up the waste.

Composting, which we’re always trying to promote and encourage, is probably the single best thing we could do as individuals if we have the opportunity to compost. In terms of waste, a good deal of waste, we don’t really know what happens to it. This just shows how much of the waste that is produced by people is actually collected.

So, we take it for granted that our waste, when we put it out, will be taken away, magically; it disappears magically, is used by, taking off a problem with ours, and must be dealt with somewhere else, not a problem. Obviously, much lower collection rates in all countries, so they get to see their problem in their actual neighbourhoods, whereas we might jettison it 15 or 20 miles down the road, where it causes problems for other communities.

The role of wealthy countries in waste production

And this, again, on that theme, shows why our decisions matter so much in this country, because we are still, despite what we might think, recently a massively wealthy country and then using huge amounts of materials.

So, you can see this is the higher-income countries, which I suppose would be the United States, Europe, the upper-middle, lower-middle, and the lowest-income countries. So, even though the very lowest-income countries are land filling and dumping the vast majority of their waste, that is sort of the real problem in their communities, but it barely registers in a global sense. What really registers is the decisions that we make, because we’re in this much bigger impact category.

Summary of waste management disparities

So, in summary terms, you have western developed countries and we’re recycling more of a heck of a lot. You have lowest-income countries recycling very little, hardly anything, although some of the informal recycling is fantastic, actually, and the use of materials is good.

You have a huge number of countries that are racing towards our sort of lifestyles, but the waste management systems will take years to catch up, and they’re possibly going to have some of the biggest impacts over the next 10-15 years.

You might have some countries that managed to make a perfect transition from,to a high-income, high-recycling economy. Taiwan, to talk about soon, is possibly an example of that. That was all the bad news, but a heck of a lot of good news in terms of waste as well.

The benefits of effective waste management

Waste management will bring improvements; proper waste management then brings improvements to health, employment conditions, environmental protection, and government revenues. You’re outsourced potentially massive economic market for recyclable waste globally. Preventing food waste could save the UK 12 billion pounds a year, which I think is about one month borrowing. So, that would help.

What could we do? What, in terms of what you were saying earlier, what could we do with the 12 billion pounds?. So, already in the U.S., you have 1.1 million people employed in reuse and recycling, and they are tending to earn higher than average wages because they’re recycling. As resources become scarce, it offers potentially lucrative rewards in terms of recovering materials.

Benefits of recycling

There are basic facts like this that we would talk to the children about, the public, and you know, just recycling one aluminium can will save enough energy to run a television for three hours. Home composting saves Derbyshire, on average, about 250,000 pounds a year, and recycling is saving Derbyshire about 8 million pounds a year, which is at a time when every penny is utterly crucial. Eight million might help keep some buildings open in the north and libraries open. Some good case studies came across looking at this tall.

Inspiring work in India

Information source – First Global Strategic Workshop of Waste Pickers

So this is in India, which is basically a highly informal system prior to 2008, really, there was a very informal system where people from the lowest caste would actually go around to houses and collect what they could for recycling. But it was a chaotic and dangerous activity, and often, because of social attitudes, some of the most valuable materials were actually taken by house maids, middle men, and the middle classes to use for their needs.

Transforming informal waste collection

And during that period, before the improvement, the people – women, primarily women – who did this would travel up to 12 kilometres a day and have head-loads of up to 40 kilograms, with average earnings of 1.12 USD a day. In addition to that, you know, the informal, hazardous sourcing of waste on the landfill sites, and you’d have issues with people being crushed by waste avalanches, vehicles, and meaningful sites, etc.

In 1993, as early as that, people who were doing this attended a conference with a local university, and because of their concerted efforts, and I presume it started with some, just a few really determined individuals, as these things often do, they began to get some recognition from the local government.

And in 2008, quite a long time, a long process later, they’ve managed to form a cooperative, which is still gradually formalizing today, and it’s the Cooperative for Solid Waste Collection and Handling Services. And they’ve got more and more recognition from the municipal authorities who’ve given them uniforms, and as with Bangalore, they’ve seen that this is really good news because it’s reducing their municipal waste fee. So they’re managing to withdraw more and more containers, which means they don’t have to send vehicles around, resources around to collect it. So we’re suddenly seeing that this is an opportunity.

Information source – Waste Pickers Lead the Way to Zero Waste By Neil Tangri; Report by Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives

Community engagement in waste management

The fact that this group of people has gained uniforms and a formed cooperative has changed public attitudes towards them. So there’s more of a willingness to give them the higher quality of materials. There’s also local composting community projects, very local, you know, sort of within villages and within the actual properties themselves.

And there’s been an incentive given for people to actually have a rent rebate for householders to actually have the composting on their site because the composting takes place so locally, and people are seeing that contamination is a problem, so they’re improving their approach to it. And the upshot is that there’s more recycling, there’s less cost for the municipal authorities, and the people in the cooperative have seen their incomes triple.

So that is excellent news, which presumably started just probably through the determination of a few individuals to change things and maybe some NGO intervention.

Zero Waste in Alaminos

Alaminos, Philippines, and this is staggering to me, because zero waste is like a dream to us, but they’re sort of getting on with it. We’ve just talked about it in this country for a long time. Where I think, basically, this is a tourist area, where there was a lot of fly-tipping—it was affecting the marine environment—where people used to come and dive and things and basically, they have a lot of fly-tipping, burning, proliferation of non-recyclables, and there were plans developed for developing a lot of incinerators.

But they ran into opposition and gradually came to a more sustainable waste management solution, sort of local composting, and they had workshops to engage with the community to see what they wanted and to really make it work. It was a mixture of NGO intervention and also the impact of eventually match funding from local authorities, which got on top of this.

And they had a project — they have rolled out the bins, they got the resorts involved, householders involved, businesses involved. They even consulted the informal junk shop, so you use the materials to sell their aeroplanes made from cans and things like that, and they got everyone enrolled.

Community engagement results

The follow-up found that 50% of the population were aware of the project. 21 after 39 village leaders attended zero waste workshops, which if we had a result like that, we would be amazed, so that was brilliant and seen massive reductions in fly-tipping. In 2003, the Republic Act (“Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000.”) required the implementation of solid waste management plans across that area across the Philippines. We’ve now got a zero-waste strategy developing, which again is amazing.

Taiwan government intervention in waste management

Taiwan is another example where, basically, in the late 1980s, there was a recognition that we were running out of space. A government solution at that stage was to embark on a massive program of incineration development, and that led to quite a lot of fierce community opposition.

But now, in response to that opposition, the government did sit down and take concerted action, and went through a zero-waste policy, and has implemented a lot of things which we would think of as quite radical, I think, and things that I would love to see, but they actually got on and did it in terms of requiring producers of electrical goods to take back materials, adopting a pay-as-you-throw system, so basically, the more that householders throw out, the more they pay.

Reuse and take back schemes for bottles and their items, banning disposable ranges of disposable items in schools—so they’ve managed to achieve massive GDP growth without the waste growth and a 13% fall in waste per person, precursor, just in that concerted action that showed sort of the importance of government intervention there.

Information source – Huffington Post article

www.huffpost.com/entry/taiwan-recycling-garbage-waste_n_5ce6bb1ae4b0547bd133ceba

Individual action and community impact

So what can I do? What can we do? Remarkably, one part of it is remarkably simple, which is what we can do in our lives because when I think about it I’m amazed that the recycling rate in Derbyshire is still under 50% because just by taking some pretty simple action, the recycling rate should be far lower than that.

So maybe the bigger challenge for the people in this room is to think about how it can influence more people out there, really. So, I think for all of us thinking about it – if we don’t think about it, just carry on regardless and adopt our same old habits. If you think about it – and you might still not do anything about it – but at least if you’ve thought a bit, there’s a slightly better chance.

Could you recover that into the chain of commercial utility? Make it useful again, the wires on his head, or whatever they are, and just pointing out that in the future projection of this, in which way we go, it’s going to rely on the trillions of decisions of individuals making decisions every day, which influence this outcome. Multiply that up globally, and you get the global solution or outcome.

Tactics for influencing waste reduction

So, if you can, occasionally tactically nudge people, influence wider circles, that can be a good thing to do. You might accidentally leave an interesting article about waste in the dentist, or something like that, or you might just point out to someone about, you know, “put that in there! Did you know you can recycle it?” Or “did you know I saved 20 pounds last month by not wasting that sort of food waste stream?” That’s the sort of tactics we use in Derbyshire to try and make it real to the individual and point out that there are financial benefits in particular; that’s a good one.

The challenge of inertia in recycling

Just remembering that there are people in my office, who must be fully aware of what we do but still do not recycle, and I still see plastic bottles in the wrong container and paper going into the wrong container; and you know these people sat across the room from me.

So you cannot underestimate the power of inertia—even of the educated people who know everything about it. It’s how you need people to make that tiny bit of extra effort, which can have a dramatic effect. Answers on a postcard, please…

Composting as a waste reduction strategy

For us in the Northwest England where we are, very basic things can help dramatically reduce the waste on the amount of waste we all produce personally. I’ve talked about composting: a third of what’s in the bin can be composted. If you have a space or a garden, we have a tiny garden; we’ve still managed to compost because you don’t necessarily need to use what’s in the bin in any significant way.

It just looks after itself, and you can keep on putting the vegetables in. Once the weather warms up, it’s quite remarkable how fast the process is, and that’s converting the material waste to water and carbon dioxide rather than the methane that it would have become if it had gone into an area as landfill.

The impact of food waste

Love food, hate waste; that’s a good example tonight. Let’s try and use all the food here tonight, take your battery. Yeah, food has a tremendous effect because of all the energy that goes into creating it – a wider environmental effect. But food will release methane if it breaks down in landfill; we can avoid it and avoid the cost of its collection by eating it.

www.derbyshire.gov.uk/environment/rubbish-waste/love-food-hate-waste/love-food-hate-waste.aspx

Utilizing furniture reuse programs

Most of us will have a furniture reuse charity shop project nearby; use it if you can. They will accept sort of working items, sometimes larger electrical items, sofas that have a valid fire certificate. There’s e-recycling things like locomotor, where you have the services in the community that are available. You can pass things on through Freecycle; people will often happily come and collect things that were a problem to you that they actually want and save you for these.

Freecycle Network:

Freegle:

Engaging the younger generation

We had a whole campaign in Derbyshire called Pass-It-On, just encouraging that thing of passing the old mobile phone on if you can. And not a popular, a fashionable thing to do but, passing on electricals. toys – can they be used for your siblings or their friends?

One of the things that we have to try and do is engage with young kids, and we have a waste theatre, waste watches a theatre performance, which is like a theatric performance that goes out to all year 8 pupils in Derbyshire and comedy and engagement through that. But there are a lot of other good things that are going to help this cause, which is the recognition by business, not necessarily through altruism, but certainly the bottom line that they need to take action, and a lot of businesses are taking dramatic action to reduce their waste.

Derbyshire County Council: Pass It On

Business responsibility and packaging waste

And there’s things like the The Courtauld [Commitment] agreement where there’s a requirement—this is a voluntary agreement by retailers to reduce their packaging. There’s a finite strength in it, a bit of a gray area in some packaging in that, by having the packaging, you preserve the food. And actually, for like a bunch of tomatoes, if you threw the packaging away, the effect of that is something like one-fifth of the effect of if you actually threw the tomato away in carbon terms. So sometimes, packaging—a tiny bit of packaging—is serving a bigger purpose.

The Courtauld Commitment Annual Report 2025

Regulatory framework and EU influence

So there’s some gray area; thank goodness for the EU—dramatic, legislation coming through from the EU and has been over the last decade or so to drive up environmental standards, increase recycling of cars, increase reuse and recycling of electrical items, protect groundwater. We were not going to really adopt the groundwater protection initiative that came from Europe.

Consumer pressure for change

So you have the pressure of the consumer and the stock market to gain accreditation and environmental management systems. I don’t think there’s enough of that necessarily – of us, as consumers, demanding a change and, you know, occasionally leaving the packaging at the supermarket till, engaging with the supermarket manager about this – because gradually that sort of public pressure does change things over the years.

Perhaps there will be more of that, I think. But once, of course, companies set fantastic examples – and the examples are there in terms of what they’ve saved financially – others follow; it’s the financial bit that matters. If they see the bottom line changing, they’re going to go for it.

Waste statistics in the UK

So, in the UK, waste is rising in 2004; this is across commercial, industrial, and household, worth 526 million by 2010, down to 177 million. Still enormous amounts that are actually an absolutely enormous score in that waste in the UK

Information source – Office for National Statistics

www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-waste-data/uk-statistics-on-waste

The urgency for collective action

So, that is the overall conclusion—these next four or five years remain critical. Sort of getting onto the right side of the road—massive action is required by, individuals, communities, businesses, corporations, and governments to salvage the situation and save the environment and the oceans. That would be amazing.

The concept of zero waste

Question: Can you say more about what you mean by Zero Waste ? Answer: In reality—in practical reality–it means dramatically increasing the efforts that you make to prevent waste. I don’t think you’re actually going to end up with completely zero waste; that’s virtually impossible.

But it’s more like an idea that means if it was adopted in Derbyshire, it could be adopted elsewhere—it would mean dramatically looking at the way that we procure things, make use of materials, and full commitment. But it seems like in the Philippines they’re managing to drive it forward as an objective in the long term. I don’t think in practical realistic terms you can ever necessarily get to zero waste.

Burning waste: Pros and cons

Question: A friend of mine burns his household waste in the back, you know, in a thing. Is that bad? He believes—he says, “oh no, I know what to burn and what not to burn, and it’s all fine.” Is that fine?

Is it possible that there are things that are okay to burn? I think it was like a backpack and some pieces of wood. That’s what we used to do; we used to burn a lot more. And it never feels like a problem now because hardly any. The only reason it doesn’t feel like a problem is that because no one else is doing it. If another five people from his street suddenly start to do it, then it would quite quickly become a problem.

So, with some— I mean, we have wood-burning stoves, so I suppose we have small amounts of paper going on to get that started. I don’t know about that; that might not be as good as recycling.

Global best practices in recycling

Question: How do other countries approach these problems? I mean, other smarter countries in the UK—countries like Sweden, Scandinavian countries, Holland—how do they deal with this problem?

The best recycling area is Flanders in Belgium, where I think they’re at 75 percent recycling. I think the rest of it is energy-from-waste, so really dramatic. And basically, it’s concerted, determined, financed, properly-resourced government action with resources on the ground.

As part of this, the talk looking at this, I was amazed actually one of the other perfect examples is San Francisco, where they again have really gone for a public engagement in a big way, and I noticed that the population there was 800,000, which is about the same as Derbyshire And they have 11 zero waste officers working on their campaign, where we have two.

So, it’s about being brave enough to make the upfront investment in equipment, public engagement infrastructure, which rich countries should be able to do because they’ll benefit, and actually, the Scottish and Welsh governments are much more proactive on this.

In terms of English policy, we are very hands-off and actually have withdrawn from some of the targets that were driving improvement. Especially left with councils with a lot less money to try and do what they can; that’s probably quite a harsh critique of what they’re doing, but you could see it that way.

Bottling return schemes and their efficacy

Question: When I was in Finland, one of the best things I saw was when you bought like a bottle of coke, it was a pound more expensive than it should have been, and then when you brought the bottle back, you got a pound back.

And there were people on the streets with shopping trolleys full of bottles which they were taking back because people were too lazy and just threw them on the floor. Why don’t those sorts of schemes exist more? Because that just seems perfect, doesn’t it? Who the hell is going to bring a bottle in, and then if you get a pound for it, but if you don’t, then someone else is going to pick it up and bring it back and get there, get the pound and then you ensure that that is recycled.

Finland’s system for returning beverage containers started in the 1950s, and today almost every bottle and can is recycled. Convenience is the cornerstone of the system’s success:

Carts of Darkness – Documentary which shows a similar scheme in Canada

Response: The reason is – I think it was about seven or eight years ago I think – retailers ‘looked at it’ and decided it wasn’t economically viable and they were not going to support it. At that point, I think the government backed off driving it really,and it just never happened. There’s this sort of inertia thing; unless you have someone who takes an idea like that, puts resources behind it, and really believes in it, and you need the economics to stack up and possibly more willingness from the corporate sector to take on board the cost of set up. One of the issues we have in this country, perhaps, is that the producer responsibility element is not quite strong enough yet.

Information source – Yahoo Finance

uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/deposit-return-scheme-misrepresented-waste-074435623.html

Introducing a Deposit Return Scheme for drinks containers in England, Wales and Northern Ireland –

Government response 20 January 2023

The producer responsibility element

You know that people who manufacture electrical goods and products, still there’s not enough cost to them. Well, the cost is still dealt with by ‘us’ and the environment. So, it may well come back into favour because in the 2008 slump, the market for recyclables went through the floor and things like that.

So they would argue that they might be left with a load of thousands of bottles that they have to deal with, but in terms of their overall profits, it would be negligible anyway. I think it sounds like a great idea. Again, I think it is a lack of general will and someone pushing.

Economic perspectives on waste management

…If we start from the point of view that everything must be decided on the basis that capital must make a profit, then you come to the conclusion this isn’t worthwhile, but it’s only if you start from that point of view. It’s only if you start from the point of view that the system must run in order to shift public money into private profit.

The impact of opportunity costs

The costs are, because the costs, you know, appear on their balance… An example of that would be electricals, where, under the producer responsibility, a lot of retailers, rather than offering to take back electricals and deal with them themselves, are sort of giving councils a bit of money to go off and do recycling projects, which will make some difference. And I’m trying to win some money at the moment to get one going, but, it wouldn’t be as easy as if like the big electrical companies said once you’ve finished with it, bring it back here.

The consequence of long-term waste management contracts

Question: I like what you said ‘We’re stealing from ourselves; we’re stealing from the future’, and I’m fascinated with, one of the concepts we find in economics, which is opportunity costs. So, you know, I’m going to shop; I’ve got a pound now. I can spend it on, on this these fruit pastels, but if I buy the fruit pastels, I can’t get the fruit juice…

Response: …which is a good one because the hand is being forced, I suppose, in some senses of councils, for example they need security, and they need to know what to do; they need to know that there’s going to be an outlet for waste in 20 years’ time.

And they need to make strategic decisions about what we are going to do for waste for the next 20 years, which means there may be a tendency to enter into long-term contracts, perhaps from ‘energy for waste’, which may or may not be the right thing to do. But they’re enormously expensive to plan, deliver, operate. What could that money have been used for in terms of zero waste ?

Balancing security and sustainability

But from our point of view, we need to have an outlet for the waste. We can’t be left in the situation where there is no outlet left because all the landfills have closed. So it’s that balance of having to have the security of a waste outlet but recognizing what it’s going to cost in terms of the other opportunities that you might have missed, like giving everyone a free compost bin.

The potential of reusable containers

Well, I love what you said about the one aluminium can can drive a television for three years. Three hours! Also, three hours! I thought three years as well! Three years – no, no, that would be good. But you know, one glass bottle will drive a Nintendo Wii for five hours.

…that’s always frustrates me about putting a glass bottle in the recycling is I could take this back to Aldi and you could just fill it back up for me. But I don’t think they’d do that because it frustrates me that the van that took the glass bottle there is going back to the depot at some point eventually. Why can’t I bring the bottle back, and you take it back to the the factory that’s filling the bottle?

The viability of return schemes

Is there ever— is anyone you know, do you think we’ll ever get to a point where that? Because it happened; it used to happen, didn’t it? Milk on the doorstep, you put the bottle back out…

…I was gonna say all that—all those used by thousands of different beautifully coloured products and all of this space is utterly crucial to the retailer in their war for for ‘market share’.

And putting in some larger containers where twenty or thirty different products could be displayed; I think that is the tension with the kind of forward thinking you have got there.

You know, keep asking; I mean, that’s, you know, consumer pressure—writing to the manager of that Aldi or whatever—or talking to them when you go in, making a headache.

The role of promotions in food waste

Question: It’s kind of like my pet; my pet notion, which I’ll never hear anyone talk about, and that is with food. All these two-for-one offers that exist, I can’t help but think that that drives waste in food because people buy things, and they’re actually buying— there’s a kind of push towards buying more of something than they would naturally buy.

So, you know, say if you’re buying half a kilo of strawberries and it’s two-for-one, but you actually only want a small number of strawberries, you might go down that tap and you…—and so for me, there is a wastage in that whole concept of how offers are done.

Legislation on promotions and waste

I know this would be deeply unpopular, but for example Aldi, you go into Aldi, and they don’t have those kinds of offers, but you go into some of the other places, like Tesco, and they’ve got a huge number of these offers.

And personally, I’d be very interested in having legislation to stop people actually creating these offers, which must be forcing wastage. Has anyone—are you aware of anyone that’s ever suggested that? I mean, I’m just thinking the negative effects.

Certainly in the alcohol business, certainly in Scotland, they have been banned, so anything like, you know—and obviously, that’s more to do with public health and encouraging people. If they can do that with alcohol why can’t they do that with other things ?

Reducing food waste

We talk to people, regularly, all the time about helping to equip them to reduce food waste. Some people haven’t thought about it and do want to learn about how to store things. Very simple things, like writing a shopping list before you go shopping and storing things at the right temperature, re-using leftovers.

Cost saving as motivation

All we mainly put that on the platform of cost saving or saving money, which people do like when they realize they might be saving 60 pounds a month on it.

Changing public attitudes

So we’re trying to fight a bit of a guerrilla war with the actual public themselves to change their attitude, which means we’ll face eventually doing supermarkets themselves. Supermarkets would say that they are doing quite a lot about packaging; like Sainsbury’s said they were committed to looking at every single product stream trying to get the best packaging solution for that in carbon and waste terms. They say they are committed to that.

Community initiatives

Question: you mentioned the idea of leaving the packaging at the till. Have you come across communities—people doing this? Because now I want to go, maybe not to my local but…

Response: Yes, I have heard about a few radical nutters which have done this…

…I might go across the other side of town and be a radical nutter!

Media influence

Again, if you could get some community momentum going, the outcome of that would certainly make a big media story. Probably, enough people did it, and that would, potentially galvanize action or open the discussion about it.

Brand discontent

Question: You say about Sainsbury’s, I fell out with them recently because they stopped—they were doing milk in plastic bags, which you bought a jugget thing for, and then they stopped doing it. So all they’ve done then is sold a load of plastic things, like, you know, actual physical plastic jugs that no one’s going to use any more.

And they claim it’s because they’ve got a better way of saving plastic, but it’s rubbish. You know, me and a couple of people tweeted them and tweeted other, you know, nothing back. So it just feels like, well… like I get annoyed because my Marks and Spencers do the same; they wax lyrical about how wonderful they are about saving the planet, but then they put everything in a really thick plastic bag for you at the till. They charge you 5p, but I mean that’s still—you’re still wasting all that stuff. It does feel a little bit like they like to say how good they are about saving plastic, but I never feel very convinced.

Personal responsibility in waste reduction

Do you take a reusable bag yourself ?

Yes, I do…

The thing is that it is not really within our remit to directly tackle the supermarkets… but you can tremendously minimize your own waste production by always remembering the reusable bag, avoiding packaging where you can, eating all the food that you buy, making sure you recycle what you can recycle, and passing things on, using furniture projects.

Just by doing all those things, if everyone in the UK did all those things, the recycling rate wouldn’t be 47%, it’d be up near 80%. So it is,—there’s frustrations about what’s happening, but we shouldn’t forget about the tremendous amount which we can individually do, and most people in this room are probably already are doing those things.

Engaging the community

The challenge for people in this room is how you influence the people in the pub out there. That’s the real challenge, and that’s what we grapple with because in Chesterfield and Bolsover areas, there’s a food waste collection service. People can just by putting materials into the right bin, recycle their food, but they don’t. So we need to look at why they’re not doing that, and it might be that they need a caddy or a bag.

Something is not right to them; the issue of putting food into a caddy that’s collected once every fortnight – it’s too big a deal. So they are more interested in the direct immediate hygiene issue in their bin than they are on the wider implications, and they’re more worried about things which we don’t feel very squeamish about; this is a bigger issue to them, and it’s those sort of people who need to influence and try and persuade to change.

Revealing what happens to the waste

Question: David, you said you were doing—uh, you were trying to find out or you have found out what happens to all of this waste. Oh yeah, this to recycling, and then everybody thinks, “oh, I’m not quite sure what happens to it,” so maybe I won’t because I don’t think that’s going to be recycled or that’s going to be recycled”. Yeah, I’ve seen an opportunity for the Ragged website. We might, take the work that you’re doing, put it on the website, and get it out there so that people do have a real sense of what’s happening to all of that stuff. Yeah, because the amount of times I hear people say, “oh, that doesn’t get recycled anyway.”

Response: We’ll probably have to accept this: the international world and some more recycling takes place in China, but that’s where so much of our stuff was coming from. The boats have to go back there anyway to collect more products; they may as well go back with the stuff that they need to make the new products from the environment.

Necessarily, the wrap reports, government reports have shown that even sending those materials to China for recycling is environmentally more beneficial than putting it in a UK landfill. But even doing that, of course, the whole industry is trying to generate more markets here so we can recycle these materials as close to the UK as possible. So there are plans for a carbon recycling plant in Yorkshire now, so things are improving in that respect.

WRAP is a global environmental action NGO transforming our broken product and food systems to create Circular Living for the benefit of climate, nature and people.

Visit the link below for their Reports:

www.wrap.ngo/resources?type=1498&field_initiatives_target_id=All§ors=All

Local council recycling practices

Question: I was just thinking about how our local council; they pick up the aluminium and plastic and paper, but not glass. So we take the glass to the special recycling ourselves. Is there hope to write to the council and say, “hey, why don’t you pick up glass as well across the council?”

Response: Yeah, I know that councils will, look at that, and they do listen to what the residents say. They do—they do really take it very seriously. But, it depends on what their financial circumstance is at the moment on what level of financial crisis – they will probably be in a financial crisis just at the moment, but that might not last forever.

And then councils, whenever they can, they will, they will try to add new materials; they are trying to boost juice carton recycling in parts of Derbyshire, and they’re just waiting for the financial opportunity. But at the moment, it’s just cut, cut, cut.

Financial implications of waste management

Question: And so, do you think that’s the county council? If I heard you correctly, the savings were eight million?

Response: Yeah, that’s the saving, but if all that recycling disappeared and went to landfill, it would cost at least eight million pounds. And it’s a crucial thing for us; it really is. If waste goes down one percent because people reuse their bags or send a fridge to a furniture project for reuse, that can save up to a million pounds a year when it’s multiplied off. Every pound is absolutely vital in the public sector as you know.

Any ideas on how to get people to use the recycling they already have are much appreciated; behavioural change – that is a big area. I’d be delighted to hear from you.

Helpful Information Resources:

United Nations Environment Programme: The Global Garbage Crisis; No Time to Waste

http://www.unep.org/NewsCentre/default.aspx?DocumentID=2698&ArticleID=9317

United Nations Environment Programme: Chemicals and Waste

http://www.unep.org/chemicalsandwaste/

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs Policy Paper: Waste Prevention Programme for England

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/waste-prevention-programme-for-england

Love Food Hate Waste: Whatever food you love, we can help you waste less and save you money

http://www.lovefoodhatewaste.com/

Derbyshire County Council: Rubbish, Waste and Recycling

http://www.derbyshire.gov.uk/environment/rubbish_waste/default.asp

Facts & figure: Watch our videos to find out how the recycling process works

http://www.recyclenow.com/facts-figures/facts-figure

Quiz Questions:

- Personal Reflection: Reflect on your own experiences with waste management. How do these experiences compare with the author’s 20-year journey in the field? What insights have you gained that could be applied to future waste management practices?

- Waste Management Philosophy: Discuss the author’s perspective on the evolution of waste management regulations from informal to formal systems. What are the implications of this shift for developing countries?

- Crisis vs. Opportunity: Analyze how waste management challenges can be viewed as both crises and opportunities. Provide examples from the text that illustrate this duality.

- Regulatory Compliance: Evaluate the role of regulatory compliance in waste management facilities. How does the author’s experience with inspections highlight the importance of adherence to environmental protection laws?

- Public Engagement: Explore the significance of public engagement in promoting waste management practices. How does the author suggest individuals can be motivated to change their recycling habits?

- Comparative Analysis: Compare and contrast the waste management practices in Lebanon and Italy as described in the text. What lessons can be drawn from their experiences?

- Community and Individual Roles: Discuss the role of community and individual actions in improving waste management practices. How do collective efforts lead to significant change?

- Innovations in Waste Management: Investigate the innovative solutions proposed by individuals and communities in Bangalore. What can be learned from these initiatives regarding the interplay of business innovation and waste management?

- Long-term Consequences: Analyze the long-term environmental and economic consequences of mismanaged waste as discussed in the text. Provide specific examples that illustrate these impacts.

- Globalization of Waste Crisis: Evaluate how globalization has contributed to the global waste crisis. How is waste management a reflection of economic disparities between countries?

- Informal Waste Systems: Discuss the effectiveness of informal waste systems in developing countries. In what ways can these systems be integrated into formal waste management strategies?

- Policy and Legislation: Explore the implications of policy and legislation on waste management in different countries. How can effective policy drive substantial improvements in waste handling practices?

- Economic Incentives: Analyze the economic incentives mentioned in the text for promoting recycling and waste reduction. How can these incentives motivate both businesses and individuals?

- Cultural Attitudes: Investigate how cultural attitudes toward waste impact recycling and waste management practices in various regions. What strategies could be effective in changing these attitudes?

- Social Justice and Waste: Examine the social justice implications of waste management as addressed in the text. How do the actions of certain businesses and communities exacerbate or alleviate waste issues?

- The Role of Technology: Assess the role of technology in improving waste management. What technological innovations are highlighted in the text, and how do they contribute to more efficient waste processing?

- Behavioral Economics: Apply theories from behavioral economics to understand public reluctance to engage in recycling. How can knowledge of human behavior influence waste management strategies?

- Environmental Justice: Analyze the relationship between waste disposal sites and environmental injustice. How does the visibility of waste mismanagement affect community perceptions and health?

- Zero Waste Concept: Discuss the feasibility of achieving a zero-waste society as proposed in the text. What are the barriers and potential strategies for realizing this goal?

- Fly-Tipping Issues: Evaluate the problem of fly-tipping as described by the author. What are the social, economic, and environmental impacts associated with this illegal activity?

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Conduct a cost-benefit analysis of recycling versus landfill disposal based on the author’s discussion. What conclusions can be drawn regarding economic sustainability?

- Case Study Review: Select one of the case studies mentioned (e.g., Lebanon, Bangalore, Italy) and analyze its relevance to current global waste management practices. What lessons can be applied universally?

- Future Waste Circuits: Explore future trends in waste management. Based on the text, what emerging practices in waste reduction and recycling could shape the future state of waste management?

- Public Trust Building: Discuss the importance of building public trust in waste management systems. How can transparency and education improve community participation?

- Environmental Footprint of Waste: Analyze the environmental footprint of different waste management strategies outlined in the text. How do these tactics align with sustainability goals?

- Psychological Barriers: Investigate the psychological barriers individuals face in engaging with waste management. How can these barriers be overcome, as suggested by the author?

- Comparative Waste Generation: Discuss the disparities in waste generation between developed and developing countries. What strategies can be adopted to mitigate these disparities?

- Impact of International Aid: Evaluate the role of international aid in improving waste management systems in developing countries. Can foreign models of waste management be effectively implemented?

- Grassroots Movements: Discuss the impact of grassroots movements on local waste management policies. How do these movements challenge formal systems and drive change?

- The Future of Waste Management in a Circular Economy: Explore how waste management can be integrated into the concepts of a circular economy. What steps need to be taken to transition from a linear to a circular model?

This event took place on 19th February 2015 at The Castle Hotel in Manchester.