Learning Artifact (Fine Edit): The Book as a Technology by Drew Whitworth

This is the fine edit of a learning artifact generated as a part of a project exploring methods by which the production of a work can structure a curriculum for active learners in their own lives.

The project especially focuses on the human as autodidactic – that is, the individual as capable of learning independently in their own context without necessarily being rooted in a formal context. It is an exploration of means of gleaning from the local environment all the necessary elements needed for the individual to go on a learning journey which culminates in personally realised human development.

Table of Contents

Introduction

This is a follow up to a previous post [Learning Artifact (Prototype): Drew Whitworth The Book as a Technology – raggeduniversity.co.uk/2022/11/28/learning-artifact-prototype/] where an account of how the creation of a ‘Learning Artifact’ may be used in order to fashion a process which exercises a range of skills in order to develop the capabilities of the individual doing the work in their own context. In simple terms, how can we utilise the environment we find ourselves in to educate our selves through activity.

This project owes a debt to a range of thinkers and educators who have been generous enough to share with me their thoughts, experience and good humour as I experiment with the notion of how the production of learning artifacts might offer one means for a diffuse and generative culture of education which can survive (and thrive) beyond the constraints of finance – something that severely inhibits the natural learning indigenous to our species.

The acknowledgments which should be done are numerous, but in particular, this project owes a debt to Keith Smythe, Professor of Pedagogy and colleagues, for pioneering a modern embodiment of retrospective assessment of learning; Susan Brown and Taslima Ivy for their ranging operationalised understandings of pedagogical techniques alongside clear practical understandings of Digital Technologies and Communications in Education that draw upon media; Drew Whitworth for his powerful explorations of learning environments and technologies, as well as his good humour in allowing a civilian sit in on his classes and presentations; and last, but not least, David Seagrave, who in many ways highlighted for me how many people are active learners and ‘doers’ in their own context illustrating how everyone carries with them a full and rich universe.

What follows in this article is a further refinement of a session where I, as a civilian, was allowed to sit in on a class taught by Drew Whitworth, filling an empty seat. By making a simple audio recording of the event it gave me the basic stuffs that afforded me the opportunity to exercise a range of practical skills in producing a transcript of what he shared on that day in the University of Manchester.

The series of experiments that have led to this point have made vivid the practicalities of building understanding from the essential rudiments, the fundamentals of experience, up. Taking on board the elementary encounter of the senses is a great starting point. I can sit and watch a tree grow, and with the right use of my senses and innate capacities, I can produce knowledge from that experience (i.e. a distilation of what I have come to know).

Next from that in common capabilities might be the power of discussion and dialogue as a means of exercising what we think we know, and finding new comparisons that help us refine our ever-working models we hold in our heads. Each viewpoint, tool and modality offers a particular set of affordances that make explicit particular aspects.

My interest is in exploring how the common instruments of knowledge (what we largely all have available to us) may be used in order to produce activities and curricula from any given surrounding; that these fundamental means may be used in order to construct all those things of higher education found set inside formal institutions, outside them in our lives. This contributes to a project of autopedagogy which can exist beyond the financiers, the centralised command and control bureaucracies, problematic technologies and constraints of situation/geography/schedule.

The main thrust of this experiment and exercise is to craft a learning artifact from recording a live presentation. It explores all the different settings, the many different processes and skills which need to be drawn upon in order to produce a document of the live presentation which has relevant resources embedded in it to sufficient to enable deeper learning into the subject.

Artifact: The Book as a Technology by Drew Whitworth

Above is the basic produced audio file along with the transcript which I have created ready for the next stage where I use the content of the recording to form a curriculum of sorts by researching the information and themes highlighted and annotating the text and audio file to ultimately become a piece of multimedia. The idea of contributing to building free knowledge resources on the internet and thinking about these as a sort of functional artwork in themselves is operative here.

The practice of creating a record by making an audio file has in general been welcomed by speakers. Over the years I have found that the majority of people doing a public presentation are happy to be recorded for non-commercial reasons. It usually takes only briefly asking the speaker prior to the event so as to not distract their attentions from the presentation they are about to do. Almost any smartphone can be used as a reasonable recording device, but there are excellent hand held recorders available like the ZOOM H1 Handy Portable Digital Recorder which is quite cheap.

The technical side of making a recording and improving its quality by using software is another opportunity which can be seen as a learning curriculum where through exercise you can develop better understandings of location recording and audio production. In this article the aim is to exercise recording and production skills alongside listening, analytic thinking, investigative techniques, secretarial proficiencies and judgement. Key in my thinking is the ability of the individual being able to do this in their own context; so this work is uninterested in the individual who needs to be motivated and instructed by another person.

Understanding Learning Environments

We’ve talked about what a learning environment is. This idea of a dynamic ecology; something that learners could configure for themselves and would also have configured for them by various institutions that they may engage with; and of course with producers like technology companies themselves.

Link to paper: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9076804/

The Question of ‘Why?’

Still, we did not really ask this question of ‘why?’. Why is it that particular technology is getting incorporated into learning environments, particularly by the learners themselves, by the users, let’s say? Also, teachers make decisions about why they use technology too, and we will start this investigation.

Exploring Affordance

We will be looking at this notion of ‘affordance’, and if you do not know what that word means, we will explore it here. There is a paper, which I’m not telling you to read, but it’s recommended reading; in other words, it’ll help you to read it and help you understand some of these ideas because apart from the first page, perhaps, it is quite a straightforward paper with lots of illustrations. It might seem old, but the examples are nevertheless good ones in this paper.

Situating Action II: Affordances for Interaction: The Social Is Material for Design by William W. Gaver

We will run through some of the key points about what affordance is and why it matters. This explanation has got a nice video of a cute baby as well; it’ll be fun. Then, we’re going to do this case study of the book. I hope at least some of you brought a book. We will look at the book as a technology, and if you don’t think the book is a technology, by God it is.

The Book as Technology

I will show you plenty of examples going back 1500 years of the book as something that developed over this time. The book is a technology that develops; it is not something that was invented all brand new one day in 710 A.D. Somebody said, “Everybody, we’ve got books now; we can use the text.”

We will do this exercise where we really look at and examine the book as a way of stepping back from the technology and really asking why it is designed the way it is. What makes it useful? Because this is the key point: things have to be useful. You can invent a technology, pour hundreds of thousands of dollars or yen (or whatever) into it, and still, nobody wants to use it because it’s not useful to you.

Understanding Usefulness

On the other hand, really strange little things can prove to be useful, and we keep them around ourselves for years, and habits develop around them; practices and routines, and so on.

(Welding clamp adaptor constructed from angle iron, bar stock, and a magnet. Used in conjunction with a welding clamp made by Don42 on homemadetools.net)

What we’re mainly talking about today is this usefulness at an individual level. What makes something useful to you? What makes something useful to a person, a user, a reader, a learner? We will be talking about this as a more collective point – the point that technologies are also shaped by various social forces including politics, economics, decision-making, the practices of institutions, and of groups and communities themselves.

A Thought Exercise: The Utility of Trees

A thought exercise; this is not a ‘right answer’ style question. A picture of a tree – what makes a tree useful, potentially? What can you do with a tree? You can do lots of things with trees. What makes a tree potentially useful?

- Branches provide cover from sunshine… It’s a hot sunny day, you’re going for a walk; I did a really hot walk in July and it was really hot, and we loved it. Trees provide shelter.

- They produce oxygen… They consume carbon dioxide to do it; trees as a whole are extremely useful in that respect.

- Absorbing water… This particular tree used to stand in my garden, but we cut it down; it had to be cut down because it was absorbing all of the water, and nothing was growing. So then we cut it down and things started growing.

- To make furniture… You can make furniture with it.

- Fruit, if it’s the right kind of tree, could produce fruit as a food source.

- Habitat for animals… Things live in it; you could climb it if you want to see things, if you’re so inclined, and so on and so on.

Context Matters in Utility

The point is context matters, and something like a tree, and as we will see shortly, something like steps, or something like this room, or something like Facebook or WeChat – it’s not useful to everybody in the same way at the same time. It depends on what your needs are at a given point in time and whether you have the capacity to make the best use of that resource.

Look, the tree in the middle there is a tree that stands outside a school in my hometown, Hebden Bridge, and it’s always got something like that on it, and people are constantly decorating it for whatever particular event is happening at the moment; probably because kids in the school do it. So, the creativity and possibilities of simply decorating a tree are endless depending on the context at a particular point in time.

Different images showing trees being used for ‘Yarn Bombing’ – a form of public art and community place making

Firewood is one possible way of using a tree… Sometimes you need stuff to burn if you’re sitting outside and it’s cold in the middle of the night; a tool like the axe would probably be helpful, or a chainsaw, or something.

(Coppicing is the practice of taking wood from a tree for usage without killing the tree: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coppicing)

The Importance of Physical Capacity

The physical capacities to utilize the affordances of something are important. For example, creatures make use of the tree in ways that their physical capacities allow them. We mentioned things living in the trees – well, that bird is a nuthatch. They can walk up and down the trunk of a tree – they can do this kind of thing. You could not do this kind of thing unless you’re Spider-Man; we are not going to be able to do this kind of thing – we cannot make use of that affordance of a tree as somewhere to stand, which is basically what he or she is doing.

You can get very creative with all of this, particularly if you think of the tree as representing wood. There are lots of things you can do with wood if you’re able to do it, but you can’t do everything with a tree. For example, you can’t pick the tree up, walk around with it for a while, and then put it back where you found it, unlike a book.

Perception of Affordances

So, the affordances of a particular thing are not infinite, but they are perceived. This is the important thing; affordances are a combination of innate capacities of a technology – whatever it is. The way that a technology has been built and designed or, like a tree, just an object; this doesn’t apply only to artificial objects like technologies or books, but it applies to trees.

We’ll see this idea applies to other features of a landscape, but also it is a combination between this notion of how something was designed, what it was designed to do, what it can do innately, but also what capacities we can perceive in it.

Can we think of new and possibly interesting and creative ways of using this thing that we might not have perceived in certain ways before? – and indeed in ways that the designers may not have perceived. I’m going to show you a video here; it’s pretty good too.

Affordance and User Skills

Affordance is a perceptional relationship between functional properties of environments and skills of individual users. The simple design of this chair (in the above video) offers different affordances to different individuals.

Exploring environments and learning affordances begins very early in life. Look at young Bennett having just learned to walk; he is still learning how his body allows him to interact with the world around him. For him, the chair is climbable, and because of his smaller size, it allows him to hide and crawl beneath it. A young adult like Moon Dazar may not be able to crawl beneath this chair, but for him, it is stand-able, affording him the possibility of changing a light bulb. For this professor, the chair is sit-able, providing a good resting place for reading.

Behaviour Settings and Interaction

Behaviour settings are bounded areas in space and time and offer multiple affordances that, when perceived, support particular behaviours. This outdoor classroom provides an area that can afford different behaviours during the day. This morning, while it’s empty, Bennett is able to expand his climbing skills previously learned on the chair. He has read the steps as climbable and is tall enough to do that on his own. Most likely, the designers did not consider this additional use.

Later that morning, a class meets in the area. The steps that were just climbed upon now provide great seating for students to listen to their professor for the next hour. It is easily perceived as a seminar setting, and behaviours within the space are conducted. As the lecture ends, it’s time for lunch; the area is no longer read as a classroom but as a social area for everyone to enjoy each other’s company and eat.

The young ones have become restless; they run off toward the lawn next to where everyone is socializing. The kids now enjoy a separate behaviour setting, one that affords running and exploration behaviour not appropriate where the others are eating and talking. If you look closely around you, you will begin to see how affordance and behaviour settings affect the ways in which we interact with our surroundings and each other.

Behaviour Settings in Learning Environments

A behaviour setting is a setting for behaviour that is bounded by place and time. We are in this room right now. A whole lot of things have come together so that we can be in this room, and I can use it to teach; it affords the practice of teaching; it affords certainly the practice of lecturing. I am here; you are all looking at me – it is no coincidence; this is called a lecture theatre. Many of you have come from a media background, and this idea of thinking about the appropriateness of a particular medium is not unusual.

Some things are appropriately watched in the theatre, like a rock concert. For example, we’d much rather watch a rock concert live with all the decent noise than on a little screen, on my phone, or a football match. Indeed, all the seats at a football match are going toward the pitch because that’s what you want to watch.

The Design of Spaces

Similarly, here we are in a behaviour setting which affords this kind of teaching. As we will see later, this is not an ideal room for the activity that we’re going to try, but I hope you found and saw the difference with the tutorial rooms that you were in on Friday, where there is not necessarily an obvious front; where you can sit around the table and it’s just smaller; it’s a smaller and more intimate behaviour setting. It affords different types of behaviour than are possible in here, and it’s not just the design of the room itself.

So, in a large and very complex teaching institution like the University of Manchester, for a start, we need a room booking system. I didn’t ask for this room – it’s tolerable, but it’s okay; I prefer the other room – the Friday room, but we had to have a room booking system that allows everybody really to know that the course EDUC70141 (itself part of a system) is a code that identifies this class – this idea of a class, and of course, within the system.

We can book this room. You will know to turn up here and show your attendance card – if it works – which is somehow coded and keyed to the same system. This technology – the fact that this room affords the possibility of doing two things on different screens is different from other rooms that do not necessarily have this particular affordance.

Perception of Affordance in Different Contexts

This one does, and all of these things have been designed into the system, but at the same time one perceives all of the different possibilities that are inherent in the behaviour setting. I don’t think this would be a great place to have lunch, really; it’s not very cosy, and it’s so steep – I worry about falling down these stairs.

I mean, imagine the baby going up there. We’d all be waiting at the bottom to catch it, but that nice little classroom in the video that they had there afforded them the opportunity to eat their sandwiches; it afforded a bit of opportunity for play; it afforded a kind of socially intimate classroom setting; it was in North Carolina State, I assume, and the weather I assume is quite nice, particularly at certain times of year unlike in the UK; but climate is part of the whole thing; in a warmer climate, we would be more likely to have outdoor classrooms, etc.

The Key Point: Affordances Offer Possibilities

The key point about this idea of affordance is that something affords possibility. You’ve obviously learned English and the common use of the word afford is in terms of cost, i.e. I can afford it, I can afford that restaurant; oh, I can’t afford that car or whatever, but it is all the same root word. It means to make something possible, and so technologies afford particular practices, behaviours, and actions; they make them possible, and they are, as I said already, a combination of what features have been designed into a technology.

All the things I’ve just said about the way that this room has been designed to afford the practice of lecturing. On the other hand, video conferencing, for example, Zoom; video conferencing would make it possible for me to deliver teaching to people who are not in the room. I did my distance learning tutorials on Thursday night, and we had people based in Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, and various parts of the UK in the evening and so on.

Remote Teaching and Perception in Technology

I was at home, and I could not have done these things without the technology, but it afforded me the possibility of remote teaching, and of course, it’s designed to do that. If not teaching them, at least meeting, but it is also about perception, and this really is a key point. If you don’t perceive the affordance of a technology, you don’t notice that it can be used in a particular way; or if you try it and it doesn’t work; or if you’re just not feeling like there is a particular need at any point to use a technology for a purpose.

If you didn’t perceive an affordance or the fact that it might not have been designed for a purpose, then you would never explore these new possibilities; and of course, that happens a lot. I’m not saying that somehow people are deficient if they don’t suddenly find ten creative uses for a paper clip every morning, but it is important that this happens.

I noticed this with online teaching; one of the differences between online teaching and this kind of thing (of teaching in a physical room). It’s very difficult to have a kind of audible background chat; it’s rude. I mean, you could whisper and get away with whispering if you’re at the back; but if you were to be heard, I’d probably get a bit annoyed and people would look around and stare at you; a fair point.

So, this room doesn’t really afford this idea of background chat while the lecture is taking place. You could do it with technology though – you might already be doing it – WeChat-ing each other, going ‘God, why am I here? The sun’s shining, it’s Tuesday morning’; and on Zoom or Illuminate or Adobe Connect or any one of these other video conferencing technologies, this is actually quite possible and actually quite interesting.

Online Lectures and Chat Behaviour

Having had online lectures and having run plenty of them, particularly during the Covid years, people used the chat box to type messages and hold different conversations that can be happening in the Zoom chat. These conversations supplement the lecture or the discussion taking place audibly using our speakers and microphones.

The Similarities of Video Conferencing Tools

Zoom and these other video conferencing tools have certain similarities and afford certain behaviours that are similar to this lecture theatre. In other words, they allow me to just drone on; they do enable me to show slides. For example, I could have run that video. I did this presentation two years ago online, and it worked fine.

Working through Zoom also affords different possibilities as well. It offers this idea of a background chat and the idea of breakout rooms. For example, we’ll split into groups in some ways later on, but it doesn’t mean we’re all in separate places, right? In Zoom, you can do that.

There are also things that are harder on Zoom. I can’t see everybody’s face, and you can’t have 85 people using the chat at once—it just gets kind of silly. Some things are easier, and some things are harder.

The Deaf Community: Origin of SMS Text Messaging

Another good example of affordances is SMS text messaging. I realize SMS text messaging itself seems a bit outdated now, and we’ve all moved on to Messenger or WhatsApp, WeChat, and all these other things. Nevertheless, we do sometimes get an SMS message, and of course, there was a time when everybody was using this technology. However, SMS text messaging was not originally designed into mobile phones for people to text each other.

It was designed into phones initially so that engineers could receive test messages. My Google Pixel 6 sometimes tells me, “Look, I need to do an update; you haven’t updated your phone for seven days.” You used to get messages saying “SIM update,” or you could send test messages to them. This is why SMS messaging was designed into phones originally.

The group that found that it afforded them possibilities for using the phone in a way that had not been done before were the deaf. People who are hard of hearing or deaf couldn’t hear phone speakers, and they realized that SMS text messaging was a way that made the phone useful to them in a manner it had not been used before.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Communication

As they (the Deaf community) found it difficult to hear because normally using that part of the earphone was not useful to them, they discovered the engineers’ test messages, realizing that SMS meant that you could send messages to people. Also, they didn’t need to be able to respond immediately—it’s asynchronous rather than synchronous.

If you’re not sure about the difference, check it because it’s important. Synchronous communication means both people have to be in the same place at the same time—it’s “sync-chronus,” meaning “same time.” Speaking in the same room is synchronous, a telephone call is synchronous, and Zoom is synchronous.

Asynchronous is not at the same time; email, text messaging, Facebook, and Teams are asynchronous. You can post a message and have it read five seconds later or five days later; the messages are still there. SMS text messaging afforded the deaf a use of the technology that actually was both synchronous and asynchronous.

You’re both texting each other at the same time, and you might as well be having a text-based synchronous conversation. However, if one of you has to break off the conversation because you’ve got to go to a class or have dinner, it’s possible to come back to it in half an hour, and your conversation is still ongoing—this was very useful for the deaf.

They started to use it, and the practice spread until, quite quickly, it became something that the phone companies noticed people were using and thus started charging us for it as part of our plans. So this use of SMS text messaging evolved over time. When we get onto the book as a technology, I’ll show you some examples of things that evolved over time.

The Affordances of Lego

Here’s another great example—Lego. My wife is a big fan of Lego to the extent that a lot of this stuff is hers. The practices that Lego affords are becoming infinite. There’s a show every year in Manchester, usually held in June or July, called Bricktastic.

I’m always taken to this because of my wife; well, I don’t mind, some of the things are cool. I mean, the stuff you see in this show is just extraordinary—all the things that you can do with it. It started out in about 1950, I think, as a Danish carpenter building these little bricks, and that was it. It started there. Lego is Danish for “let’s play,” in case you didn’t know. Well, it’s from the words anyway, and now you can do almost anything with this.

I mean, that Lego figure on the right is at least five feet tall; Lego therapy—it’s possible. People do this kind of thing; it’s like art therapy. This was a whole exhibition of Lego where you had kind of historical scenes. That’s supposed to be the agora, the democratic forum of ancient Greece. The Lego sculptures can be really huge. This picture of the people at the top—somebody brought in a bunch of Lego, and we were using it to think through and brainstorm ideas in a meeting at work.

The affordances that people have found for this basic idea of a plastic brick that can fit onto another plastic brick in various colours are just extraordinary. If you ever want to win a bet with a trivia question, the answer to the question, “Which company in the world makes the most tires for cars?” is not Dunlop or Goodyear; it is Lego. This is true. Lego makes more tires by number than any other company in the world for its little vehicles.

Gaver’s Exploration of Affordances

I said I would talk about Gaver’s point. Gaver starts with this exploration of affordances. It’s a key point that this applies to really everyday technologies, like door handles.

That’s a bit cruel, but hey, funny cartoon anyway. I think, right—somebody’s completely failed to notice that the door handle is pulled. This is all in Gaver’s paper, so have a look.

Citation from Gaver’s paper linked to earlier in article:

Warren, W. H., Jr., & Whang, S. (1987). Visual guidance of walking through apertures: Body-scaled information for affordances. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 13(3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.13.3.371

User Experience with Digital Interfaces

Some of you have Apple Macs, some of you have PCs, but the basic idea of a scroll bar remains the same. If you’ve got what looks like a button on the screen, it’s not an actual button—not a button like I have here. You’re not actually pressing it. What you’re doing is clicking on your mouse button, and the software, the interface, translates this notion that a click on the mouse button means “do something with whatever’s under the cursor.”

If that thing looks like a button, then a button on screen affords pressing, but it doesn’t afford clicking and dragging, for instance, like a scroll bar does. We’re all familiar with the idea now that it means there’s something above and below where we already were in a digital space, so we can scroll up and down by clicking and dragging on the scroll bar; or, of course, for Mac users, using two fingers on the mousepad.

I’m one of the 10 percent that does it my way, where you scroll down, and it goes up. Are you one of the 90 percent who really confuses me with the configuration so you’re moving down? Why would you have it that way around? I just don’t understand it because I feel differently. I feel like it’s more useful the other way around, but all of these things are becoming conventions that we are familiar with. They’re all based on this familiar idea of pushing, pulling, clicking, and dragging. Our hand movements are translated into things on the screen. There’s plenty in that paper.

The Process of Utilizing Affordances

If you wanted to make use of the affordance of a tree to build furniture, you would need to have some kind of axe or chainsaw—not to mention a sawmill, probably—and lots of other technologies along the way, such as a hammer, chisel, and nails. Nevertheless, you could turn a tree into a chair eventually if you had all the necessary tools and you had all the necessary awareness of how to link all of these possibilities and these affordances in a chain.

User Responses to Digital Designs

You want to get a response from that button you clicked; you want to see something like that. You click on “update,” and this is my WordPress blog—one of them anyway. You click on “update,” and it turns to “updating,” and that’s good because that feels like, “Oh yeah, I actually have done something.”

The Importance of Feedback in Digital interfaces

You get a little click on your phone sometimes, or when I’m putting my pin number into a cash machine, you get a little bleep sometimes, but not always. I’m not always happy if I don’t get a bleep, or I need to see the little asterisks when I’m putting in my password or pin number to see if I’ve put in enough characters.

All of these things help; they matter. They make this digital interface easier to use; they afford these possibilities. If you take these ideas more broadly and think about the design of educational technologies and what makes them useful, these little things can just be the helpful things sometimes.

If you don’t get a response of any kind, you wonder whether you’ve actually done what you thought you were supposed to be doing. I’m sure I’m not the only one who would click on it about five more times, and then you realize that you bought something five times. That’s why it says never press refresh while you’re doing this.

Sensory Experiences and Affordances

Affordances can be tasted and smelled. Milk smells bad when it goes off because our body is saying, “Oh no, don’t drink that—it’s full of bacteria, nasty thing.” Rotten meat smells awful, so you don’t eat it. If you get a cake that comes out of the oven looking like that, you’ve done something wrong. This is feedback.

Your cake comes out of the oven looking like that, and you did something wrong, and it’s trying to tell you this. Food, its texture, its taste, and its smell—all of these things are part of it. They help us build up a picture of the resources around us in the environment: which ones are attractive and useful to us, and which ones are not. This applies to technology just as it does with anything else. You might not smell the affordances of technology.

If these phones were just that little bit bigger, they wouldn’t fit in our pockets. I know pockets are not designed into women’s clothes often enough. My wife always complains about this. I can put my phone in my pocket; if it’s a bit bigger, I couldn’t. If it were smaller, I would struggle to see it. It’s got to be a certain size for me to be able to read it and use it. So there’s a kind of optimum size for technology sometimes, and all of these things are important.

The Importance of Perceived Utility in Design

Good design of educational environments, good design of technologies generally, and good design of just about anything is not just about the content. It’s not just about adding functionality upon functionality; it is about how well the users perceive a particular resource to be useful to them. Is it useful? Can I make use of this? Can I make use of this without spending six hours to learn to do something that’s just going to take me 20 minutes? Can I learn to do something quickly and easily? Do I see how I can make use of this tool?

Introduction to Books as Technology

What I’m going to do is start to talk about books. I’m going to just show you this quick film now. I’m going to show you some examples from books. I said the book was a technology, and the book is very definitely a technology. It is a technology that people have adapted and learned to make and to use in various different ways over the years, and I will talk about some of this.

The Historical Context of Book Production

We laugh, and they are taking the mickey slightly, but some of the things that they were talking about are actually extremely shrewd. I got interested in the medieval book. I think it is interesting to look at the ways that information practice is evident in the ways these books were made and particularly the ways they were used.

What you have to realize is that books were a technology that people had to learn to make and had to learn to use. They had to learn to make them in ways that were economical and effective, transmitting the information from book to book. When you were handwriting books—before print—books would be written by hand. This is a complicated process that involved lots of stages.

The Craftsmanship Behind Medieval Books

These monks didn’t go down to the nearest shop with their five groats and buy a nice blank book so they could come home and start writing, like we might do now. For a start, you had to make the book from scratch. Books were made of parchment, not paper. Do you know what parchment actually is? No—it’s not made of wood. Parchment is skin, usually calfskin.

So you had to skin the calf, you had to tan it, you had to treat it, and you had to stretch it. This was expensive stuff, and it couldn’t be wasted. Parchment was often used and reused (known as a palimpsest), and some very famous scripts, some very famous texts, actually only exist sometimes as bindings for other books. They were found because the parchment had been re-used to bind another book. The ink would be scraped off and written on again and again.

The Prestige of Ancient Texts

Really expensive and prestigious books, like the Lindisfarne Gospels—the Lindisfarne Gospels is a very beautiful, huge book as well—was made of unborn calf vellum. How you go about getting the skin of an unborn calf, I don’t even really want to think about, but that’s the softest and most prestigious material. Parchment is expensive and valuable, and of course, it took a lot of time to copy a book.

The Collaborative Nature of Book Writing

New books appeared during the medieval era, but it was very rare for someone to actually sit down and write a book in the way that I might do it. Even the books that I’ve written still needed technological devices such as a printer, a publisher, an editor, and a proofreader. An author of a book in the medieval era might have written it—there were some people who did both jobs. Usually, you would be dictating it, then the author would be a scribe who would write down the words of a famous speaker or the book that you see here.

Understanding the Codex

The technical term for a book that we might use now is actually a codex. So, a single codex or book might contain various different texts in it. It might be a compilation because, again, parchment was expensive. Libraries didn’t have a lot of space in them, and books were heavy, expensive, and difficult to carry around, particularly if they were over a certain size. A single codex might contain many different texts, and you had to find your way around this.

Early Books: MacDurnan Gospels

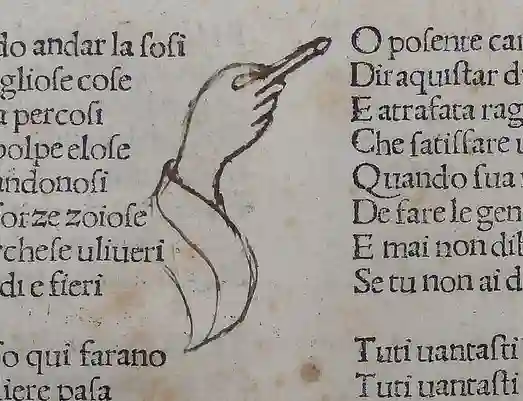

This is an amazing book; it’s called the Mac Durnan Gospels. I saw this book last summer; it was created in about 750 A.D., so that makes it about 1,300 years old. It is beautiful; it’s a lovely book. For a start, what you will see in the writing is that it’s all in Latin; it’s not very big. You can see the size of the finger there, but there is a lot of space around that.

The Value of Parchment

I’ve already said parchment was really expensive and valuable, so why leave all this blank space? What you see there was probably written anywhere from 100 to 200 years after the original text; not just two years, but possibly centuries later. Those are marginal notes; it’s what’s called a gloss. It’s a commentary. You see the blue and red letters there; you see the blue letter. Below it, there’s a little note between the two lines; people used to do this kind of thing and still do.

Writing Marginalia in Books

You’re not supposed to do it (write on books). Technically, the library should tell you off if you’re writing in books, but I’ve done it all the time. I like reading other people’s notes as well; I think it’s great. Seriously, I like seeing what other people thought was interesting, and this is partly the point here. Do you see the little hand? You see the little hand at the top between the two columns? This is somebody saying, “Look here! Look at this thing!” It’s called a diaper, and it’s what people used to do.

People learned to do this kind of thing, so it not only became acceptable to put this little thing on and say, “I’m telling you what’s interesting here; I’m giving you a commentary, an annotation of this bit of learning,” but you also had to be able to read that, and this is this idea of developing what I would now call information literacy or technological literacy.

People became familiar with the signs and symbols that said, “Look, here’s something interesting.” This is scholarship that developed over time, and these are various different ways that people introduced telling somebody else what’s interesting in the book – what’s useful about this book – to make it more useful.

Reading Practices in Early Times

When they first wrote things down, so few people could read. Publishing a book was not something done so people could put their feet up at the end of a hard day’s slaving in the brewery or whatever in the monastery and say, “Oh yeah, the latest novel from the Venerable Bede is out.” [Bede, also known as Saint Bede, was an English monk, author and scholar]. You didn’t do that kind of thing. Books were there to transmit information.

If you couldn’t really read, certainly there were very, very few people who read books out loud, except in prayer which is different. You didn’t need spaces between the words. A lot of early books don’t have spaces between the words because you didn’t need them. But as more and more people started to do that, you’ve got spaces between the words you can see. Here, the spaces are marked with little dots, and some of these are just abbreviations, so people had to learn the abbreviations as well.

Books of Hours

People annotated books for all sorts of reasons. This is a Book of Hours; a Book of Hours is like a religious prayer book but not for priests. A Book of Hours is the kind of thing that you would carry around with you if you were a noble or a lord; it’s like a status symbol. It was like a Filofax for the ’80s or your posh phone – you should have a Book of Hours, and a Book of Hours basically gave you the prayers that you were supposed to say at particular times of day; hence “the Book of Hours.”

It would also give you a calendar; what you’re seeing here is the calendar at the front of the book. Thinking about all of the ways in which a book like this is made useful to people, you had to be able to find your way around these prayers. If you just simply got a book full of prayers – big deal – the point was to help you work out which prayers you should be saying at which particular times of day and indeed which days of the year.

So you would have a calendar at the front of the Book of Hours, which this is. Those initials you see there are the names of the days of the week. Some of them are in red because the red days are special days; they are feast days, festivals, or saint’s days – hence the phrase in English “red letter day.” If you have heard this phrase “a red letter day,” it is an important and prestigious day or sometimes a dangerous day – a significant day. It comes from this phrase.

Richard III’s Book of Hours

This Book of Hours was owned by King Richard III – as in Shakespeare’s Richard III was supposed to be a sort of evil king. If you think that the British royal family has been this sort of unbroken progression for hundreds of years leading to, as he is now, King Charles III – that’s not true. Kings were slaughtered, bumped off, imprisoned in castles, starved to death, and killed with red-hot pokers and stuff like that.

Historical Context

King Richard III was, I believe, the last English king to die in battle leading his troops in 1483. Anyway, he was considered something of an evil chap, but perhaps his reputation was undeserved and, anyway, Shakespeare wrote about him. This was King Richard III’s Book of Hours. That writing that you see there says in Latin, “On this day, King Richard III was born in Fotheringhay, Yorkshire.” I think Richard III wrote his birthday in his diary – I love it. He’s got his calendar and he says, “It’s my birthday; I’m writing my birthday.” This is actually what it is.

So you can annotate books; you can write on them, you can personalize them, and you can have some really quite remarkably beautiful illustrations like that one. I’ll come back to that table of contents in a minute. So in all of this blank space, people might have written their notes and stuff like that.

Understanding Manuscripts

Now I would not have known what that was had not Professor Michelle Brown taught us; she really did know absolutely everything about everything that had happened in Europe before about 1400 – and I mean everything. So she explained what these were; these are the gospels [see above section], like I said, the Mac Durnan Gospels. I am no Christian expert here, but the four gospels – Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John – a lot of them sort of tell four versions of the same story. They’re like reboots or remakes of Christ’s story.

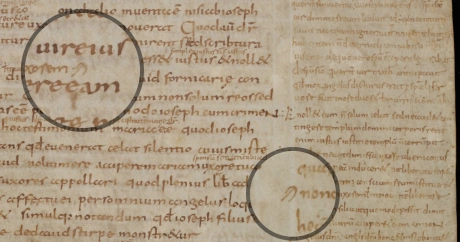

Some tales, like the feeding of the five thousand, appear in more than one gospel. Some of them appear in only one gospel; some of them appear in all of them, some of them appear in maybe two or three of them. What you see here is a medieval – actually not even medieval; this is 750 A.D. This is a cross reference; it’s like a footnote. So this whole idea of the academic footnote starts here.

[Different example drawn from medievalbooks.nl/2014/12/19/the-medieval-origins-of-the-modern-footnote]

Early Scholarly Notation Practices

What this is, actually if you look at the top box; we must be looking at John here because what you see at the top, the little number two at the top looks like an ‘m’ and a ‘t’ with a line over it and then an ‘l.’ The ‘m’ and the ‘t’ stand for Matthew, the ‘l’ is the Roman numeral 50: verse 50 of Matthew or chapter 50 of Matthew. Similarly, Mark chapter 41 and Luke chapter 56. The same story that we are looking at here, the same bit of the gospel is cross-referenced to say this also appears in Matthew chapter 50, Mark chapter 41, and Luke chapter 61.

Some examples of notation in old western manuscripts:

Most common technical signs in the early medieval Western manuscripts (OLD VERSION) By Evina Stein

Evolution of Tables of Contents

People wanted to find their way around things, and what you see here is one of the earliest tables of contents that existed. How we use information is something else that has evolved over time, and it evolved for these guys too. We are talking hundreds of years here, but over a long period of time scholarship changed when the Mac Durnan Gospels were written – and pretty much throughout human history up until about 1000, towards the end of the 11th century – so about 1080, I think the first university was founded, but until that there werent any universities, people did their scholarship in monasteries.

Example of an early table of contents:

f. 41r, Macer Floridus, De virtutibus herbarum , 1493, 10a 159

Taken from: histmed.collegeofphysicians.org/medieval-monday-15/

Monastic Education

That’s what you did if you were a monk. You might have, I suppose, had a non-religious outlook, but if you wanted access to the knowledge of the world, you needed to at least profess a religious outlook and get into a monastery one way or the other. The way that people used to study these great works is that they would do what’s literally called ‘meditatio,’ which is from where we get the word ‘meditation.’ The Latin word for a particular style of learning meant to sit and engage yourself with one book for a very long period. You would study that book in its entirety. Everything about it; you would meditate on that one book.

The Rise of Universities

Things changed when the universities began. The first university in the world? Does anybody know? And it’s not in Britain; we were second. It is in Italy; the University of Bologna in Italy is the world’s oldest surviving university. 1080, I think. Oxford is second, about 1096. When these universities opened, the style of scholarship changed. Instead of looking at one book for a long period, you did pretty much what we’re asking you to do now, which is look at a lot of them; synthesize knowledge from a number of different books, and this was called ‘lectio.’ It’s the origin of modern scholasticism.

A history of Bologna university extracted from: Rashdall, H. (2010). The universities of Europe in the Middle Ages. Cambridge university press. Page 89 to 268

Access to Information

The point [of a table of contents as a technology] is that you needed to get access to the information in that book more quickly than you did before. To simply have worked through the entirety of the book, hoping that eventually you would find the bit you wanted is what you were doing; you would spend a year reading through a book. You didn’t need instant access to information unless, in the past, you were a priest – which is why you had that cross-reference earlier because if you wanted to put together your sermon, you wanted to find out who did all the different stories in the gospels.

Tables of Contents and Navigation

Once you get to the stage where you’re looking at lots of different books, you need information quickly. This table of contents, which is what it is, was added to that book about 200 years after that book was first written. Somebody wrote out a table of contents and bound it into the book up front; previously there hadn’t been one. They decided that the table of contents would make that book more useful; it is as simple as that. A way of navigating around the information that is within the book.

Illustrative Functions in Books

Illustrations like this, which is another Book of Hours; in fact, it might even be Richard III’s Book of Hours again. Also, bearing in mind that a lot of people couldn’t read. They might not be completely illiterate, but they would struggle. Images helped, and what you actually have here are pictures. Firstly, you’ve got Capricorn on the right-hand side – that’s Capricorn; so that’s a zodiac sign saying this is the sign of the zodiac for this month. What should you do when it’s Capricorn? You should slaughter your hogs; kill those pigs, man, brine them, preserve them, salt them; get on with it.

[This book of hours is open showing the end of June and the beginning of July Calendars in medieval books of hours were typically decorated with the zodiac signs and labors appropriate to each month. On the left-hand page, June is represented by the symbol for Cancer. On the facing page, the labor of the month for July in this manuscript is represented by a man reaping.]

libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/4228

The Role of Images in Literacy

Little pictures would guide people through the story – illustrations developed to help people who couldn’t read. I showed you the Mappa Mundi; similar idea, all of the illustrations and the text on the map working together to help guide people who could not read. So illustration, it’s not just something that makes a book look pretty, but it’s something that might help you understand the information within it and navigate your way through it. Also, Early musical notation.

Above a section of the Mappa Mundi

Click to download large image of Mappa Mundi

Example of early music notation taken from:

mymusictheory.com/more-music-theory-topics/the-evolution-of-music-notation/

Comparing Books and their Innovations

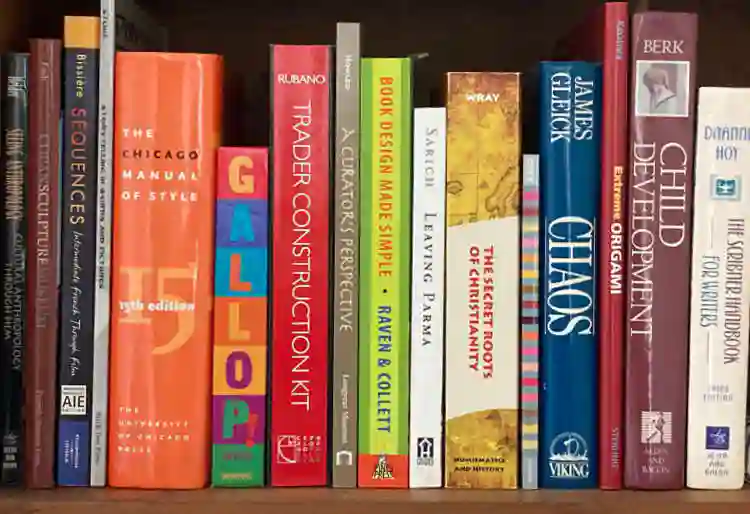

It’s time to take a couple of minutes to begin this task of looking at books. So get your books out; if you’ve got books, get them out. [At this point all the students are asked to take out an example of a book they brought to the session]. Just to sum up some of the things that were just said and some of the things that come out of the video. So that’s a picture of the table of contents again. We laugh at the two Norwegian monks for saying, “Oh, I need a guide to the other book. How do I use this book? I have to have a guide to it,” but this is actually what this is. This is a real-life example of a guide for the user; it’s what a table of contents is.

The Evolution of Book Features

None of these things are unique and innate to the book. I am hoping that in the room there will be books that have page numbers and books that do not. There will be books that have page numbers but don’t need them. Think about this, just hold these thoughts in your mind. Do you need page numbers in every book that has page numbers? Most of these books didn’t have page numbers; page numbers were pretty late to development.

Alphabetization in Historical Context

Alphabetization, alphabetical order – most of you are Chinese; you don’t have an alphabet. Well, you don’t; you have script – it’s different. You don’t have an alphabet. I have no idea how you arrange things in your dictionaries, but it must be certainly not a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, etc. The alphabet is a completely arbitrary order. Why is the alphabet in the order that it is? I don’t know. The alphabet is a completely random order of stuff, but it is an order that we are all familiar with largely.

The Historical Development of Ordering Systems

The alphabet is not an order that is somehow natural or innate or correct. It is an order that has developed over a long period of time, and the first scribes who used it; the first recorded book to be created in what you might call alphabetical order came in about 1100. It was such a new and radical thing that when subsequent people copied it, they didn’t understand the point of that alphabetical order, so they didn’t copy the order, and it was lost again for a while before it came back in about 1200 or the 1300s.

Changing Attitudes Towards Ordering

People didn’t want things in alphabetical order in the past; they wanted things in logical order or chronological order. The Bible, at least the Old Testament, is essentially in chronological order: Genesis, Exodus, the other ones, Leviticus; this is the story of the Jews essentially in chronological order. People would discuss things in logical order. If you used alphabetical order, you were seen as a bit of an ignoramus because you were seen by some as admitting to everyone else that you didn’t understand the logical structure of the argument and points that you were making. So putting everything in alphabetical order was seen as somehow ignorant because it was a cop-out, and you didn’t have to think about the logical order of things.

The Familiarity of Alphabetical Order

Now we use it; now we’re familiar with it. Some of your books will be – I’m assuming – in alphabetical order; I know a lot of mine are anyway. Please, please try to really take this task seriously. Don’t just have a cursory look at the book – ‘oh yeah, it’s a book, put it down and do WeChat for the next 20 minutes.’ I’ve got three that I’m just going to hand out. Please really consider this task seriously.

Affordances of Books

Look at the affordances of the different books that you have; there are two different types of affordances going on here. Firstly, look at all of the books as a set; I did not ask you to bring in a scroll or a phone or a TV – this is a different medium, the book. All of these books have certain things in common; that’s why we call them books.

Discussion of Book Features

So think about, firstly, what is the affordance of each book? What does every book have? What kind of behaviours does it make possible? What can you do with these books that you can’t do with certain other file formats? And if you’re not thinking of anything now, talk to people in the room about this; look at the book, feel the book, consider the book, reflect on the book; what behaviours does a book make possible? What can you do with a book? All books.

Comparative Analysis of Book Formats

There are things that every book in the room has in common with every other book that are innate to it as a file format, if you like; but then think about the different types of book that are in the room. Think about the different types of book, whether they’re in Chinese, English, Javanese, or whatever. Think about the different types of book and how these books are made useful to you as a user of the information that is in that book.

Every one of these books will be helping you navigate your way around this. So look at the book; talk to each other about books. I am going to pass out three books, and I want these back, particularly “Watchmen.” This is one of the greatest books ever written by the way, but it’s unusual; you will see why. So please really look at books, really feel them, think about them; look at the ways that information is organized in them. Step back and think, “Is this book useful to me and why?” – not because of the content of the book, but because of the way it’s designed.

What is similar to all of these books, and what is particular to different types of books? And if you really feel that you’ve had enough of the books that you’ve got, swap them around – circulate the books. There are many different types of book in the room; move them around, swap them, look at different types of books; look at lots of different types of books – this is a very active task.

Talk to each other; try to use the book. So, for example, how would you find something? There are two different ways that you could use the information in that book. If I wanted to say to you, “How would you get from a particular place?” If you want to find a particular street, there it is.

Understanding the Book as a Medium

So, I think that’s [Watchmen] a great novel, right? That is a great novel, right? But what’s unusual about it? It has pictures; it is a graphic novel. There are lots of different types of information in a book; it does not have to be words. Think about the ways that you might make a book more useful to yourself. Books on screens do not count; we are looking at paper books.

The Utility of Non-Linear Reading

Think about a book that is not designed to be read from start to finish. Where’s my metro book? Look at the maps in that book; talk to each other about those. What about the maps in that book? Are they easy to use? Why are they easy to use? Why isn’t the metro map easy to use? Metro maps are not like normal maps; they are different, okay. What helps you use that book? Talk about how you would use a book. How do you read a book? How do you find where you were finishing the book the night before?

Common Characteristics of Books

If you did that task actively, you should have access to some of these questions, or at least opinions about them. So, what is common to all of these books? Let’s start with the basics. What is shared by every book in this room? They are sources of information. Think of this as a file format, but it is a file format that has particular features. For a start, a book can be open or closed. This matters – a book can be open or closed, so what does every book have that allows you to close it, for example? A cover. Look at your book covers; does anybody have any books with a completely blank cover?

I am serious; there will be some. Right, you have one. That is a library book. There’s one; they are probably blank for one of two reasons: one is that they will have been rebound by the library at some point, and/or they will have had a dust jacket that has been lost. I’m going to show you a film, and you’ll see an example of this. What is common to all the others is that the covers are not blank; there are things written on the cover.

So, what is on the cover of these books? The title, the author, publication information; on the back, there will probably be a blurb or an abstract of the book. Why are these things there? Why put that information on the book? To attract people to buy it; to also help them decide whether they want to get it off the library shelf and whether it’s worth their time. It’s an abstract – it’s a summary of the book. Some of the books have information on them to make them more useful. I will show you the examples of this that I put on my little film.

Physical Composition of Books

Books also have another thing in common; they don’t just have a cover – what’s inside the book physically? Not words, physically; what is it made of? What is a book comprised of? What do these books have? Pages. They have pages – a book is made of a number of pages. These medieval books that we were looking at… you don’t chop up a skin – a parchment – into these pages and then file them individually; you fold the parchment and create what’s called a ‘choir’. A choir is a number of sheets, usually eight; you then cut them, fold them, and bind them separately inside the books.

Different choirs were often given to different scribes, and one of the ways that medieval scholars worked out who wrote what is by looking at whether the handwriting changes. Often, you see books where every eight pages the handwriting changes because they farmed out the job of writing it to several different scribes, and each one of them got a choir. So, the idea of a page is something that’s developed over time but is not necessarily natural.

Navigating Books and Page Numbers

People didn’t use numbered pages, but you can do various things with every book simply because it’s created in part of pages. How do you know where to pick up a book again that you had to finish the night before to go to sleep? So we asked the question: does every book need page numbers? Okay, some of you had novels, right; does a novel really need page numbers? Someone said, “Yeah”; there’s no right answer or wrong answer.

You would remember the page number where you were. I wouldn’t have the slightest idea what page number I was on; I would put a bookmark in. You can do that with a book, okay; never, never turn the corners over. I might write in books, but turning the corners over – that’s immediate death, okay, execution. Put a bookmark in to mark where you were. You can do that with a book, and it’s really easier to do that with a book than it is with a computer. Like I know now that our computers will open up files where we were before, but this doesn’t always make it easy to jump between books – to move constantly from one part of a file to another part of a file. So we can put bookmarks in.

The Structure of Novels

Why are we saying that novels don’t necessarily need page numbers? Because how is a novel read? How do you typically read a novel? Do you start halfway through? You would read it start to finish, right? There are plenty of books in this room that are designed to be read from start to finish. But there are lots of types of books in this room that are not designed to be read from start to finish. So we’ve got study skills books; a textbook; the Bible; a dictionary.

The Organization of Different Book Types

Let’s take the dictionary. We have a dictionary here; German-Spanish. What’s the Spanish word for ‘fenster’? Tell me how you would find that in the book that’s not alphabetical? We have a dictionary phrase book; now I just asked Claudia a question here because I thought it was organized alphabetically – ‘fenster’ is the German word for window. I thought you were going to be able to look and go to ‘f’, right? But that book is organized by category, not alphabetically, so maybe it’s less useful for a query like that, but maybe it’s more useful if you want to actually go to Spain and order a beer or get a hotel. So, it’s a phrase book rather than a dictionary.

The Importance of Organizational Structure

Does anybody have a book that is organized alphabetically? There is a system in the book; the book is not just a random series of words, right? It is not just a random series of concepts or events. It is an organized structure for finding the information that is in this. Dragging this back to educational digital technologies for a moment, I hope that you at least find my Blackboard site reasonably okay to navigate. I hope that you can at least follow the chronology of the weeks and the blocks; it’s arranged in chronological order, my site – that’s the way it is.

There is a top level of the hierarchy that is the blocks, and then within each block there are the weeks, and that’s how it is. So there is an organizational system in place here. Claudia’s dictionary or phrase book is organized categorically, by category, but not by alphabet; some of you have got a book that is organized by alphabet. Now, not all of the information in these books is textual. There are plenty of books here with illustrations of various kinds – even that textbook has illustrations in it. They’ve got pictures, diagrams, graphs, charts, and so on.

Exploring Visual Literature

“Watchmen,” that book really is one of the greatest novels ever written, and if you’ve never read it or even seen the movie, you really should; although the movie’s got one really grim bit in it I can’t watch – when you see the guy walking up with a chainsaw, my advice is to close your eyes for 10 seconds. What is unusual about that book, but in terms of it being a novel? That is a graphic novel; that novel is told mostly by pictures, not all of it, though.

If you flick through that, you will see that there are some passages of the book that are text; they’re words, okay. There’s one reason why it’s such a good book, really – it is a work of genius. You had the history of comic books up there. Are there any other books where the visual is important? It’s a comic; a manga. Are there any photo books, for instance, or books of pictures? We had “Lord of the Rings”; Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter’s illustrations.

The Unique Features of “Lord of the Rings”

“Lord of the Rings” has lots of maps. “Lord of the Rings” is interesting because “Lord of the Rings” is one of the very, very few novels I have ever encountered that has an index. At the end of volume three of “Lord of the Rings,” there is an index; I assume they still print the index in the modern volumes. I hope they do. But most of the time, you don’t need to find your way through a novel because you’re doing it from start to finish, but if you’ve got a book that you need to jump into, it matters.

Analysing Phrase Books and their Organization

So, we’ve got a phrase book here, but one that is organized partly around pictures and so on – that’s quite interesting. Textbooks; chapters in books, if you’re not planning to read the whole of an academic book but you just want to know one chapter, there are different ways of finding it. You would find it by looking at the table of contents, but you might also look at the back where there’s an index.

Understanding Tables of Contents and Indexes

Now, what is the difference between a table of contents and an index? There are differences. An academic book – or a reference book – does it have both a table of contents at the front and an index at the back? Yes. If I want you to find which page chapter five begins on, which one of the two would you look at? The table of contents. If I were to ask you which page the idea of post-modernism appears on, where would you look? The index. Two different pointers to the same information.

The Role of Atlases

The A to Z of Manchester; the Manchester guidebook. This is pretty old-fashioned; nobody uses these anymore. This is a road map of the whole of Manchester. You would use Google Maps now, but this is an atlas; think of this as an atlas. I will bet you every atlas still looks like this; I’ve got atlases at home – because they’re too big, I didn’t bring them in. If I want to find the information in here, I would do it in two different ways depending on how I was going to use it.

At the front, there is a kind of summary of all the pages. So, if I want to go from this bit of Manchester – which is kind of Bolton – and say I wanted to go from Bolton to Rochdale; Bolton is there and Rochdale is there. If I wanted to do that drive, I would know that Bolton’s pages are 32 to 33 and Rochdale’s pages are 26 to 27, and I can turn to Bolton. If I wanted to do the journey using this book, that’s how I would start. But if I wanted to find a particular street, say I wanted to find the very wonderfully known Whitworth Street, which is, of course, named after me – I would look at the gazetteer.

Whitworth Close – that’s grid reference 1a – page 100. What I’m looking at now is the gazetteer at the back. This is an alphabetical index to all the streets that appear in this atlas. This would be absolutely no use to me if I wanted to drive from Bolton to Rochdale. If I want to find a specific street in Rochdale or Ashton or wherever, I’ve got another index – I’ve got another way of organizing the material. So, I’ve got page 100, 1a. Here, the page numbers are really important. Page one hundred, row one, column a.

There is a system for pointing me to the right information in this book, and if I want to find a particular street, it’s much easier to do it through the index at the back than the table of contents at the front. But if I want to find more general information – in this case, how to do a broader journey, I would probably go to the map at the front, or you would find the chapter that you needed from this book at the front. Different ways of organizing the information to point people in the right direction.

I’ve got one more film to show you, but we’ll finish off with this. Because when it was the COVID years, I couldn’t do this class, so I got my son to put this together. His camera work is a bit odd at times, and there are points when you’re kind of looking at my hands rather than me.

The Book as a Technological Medium

Some points to summarize what we’ve been talking about here, okay: Hello everybody. In this film, I want to give you an introduction to a very familiar technology. Indeed, it’s so familiar that you might not even think it is a technology. But it’s been around for hundreds of years, and despite frequent claims that we will soon not see them anymore, many more millions of these are still made every year. It is the book.

Features and Affordances of Books

I want to think about some features of the book as a file format, if you like. I want to talk about things that books have in common, and I want you to think of and remember the idea of affordance. The idea that people use technologies because they are useful. So, let’s ask: what makes a book useful? Obviously, books come in all different sizes. I’ve got three here ranging from this booklet which has thirty-two pages; this short novel which is 169 pages; and then probably the biggest single book I have is Stephen King’s ‘The Stand’ which is about 1325 pages. The thing is, though, as soon as you look at how long it’s going to take you to read, no one is going to pick up “The Stand” and imagine they’re going to finish it in two days.

Personal Connections to Books

This is one of my favourite novels; I bought this copy of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” at a gas station in Pennsylvania, USA, in 1989, and I’m sure I paid about $2.50 for it. It is battered, but it’s still very readable; it is not a file format which is going to go obsolete overnight. I must have read this novel over 20 times for my $2.50. That is good value.

The Durability and Longevity of Books

Talking about durability, this is the oldest book I own; at the bottom of the front page, you can see it’s printed in 1751. I believe that is still quite readable; there are some beautiful pictures – even if it does print ‘f’s instead of ‘s’s – so a little old-fashioned, but we can still use it. Now, let me ask you, would you do this with your laptop? I wouldn’t get into a bath full of water with my laptop, but then again, books are heavy, particularly when you’ve got a lot of them; they take a lot of storage space too.

The Adaptation of Book Formats

They have developed over time some adaptations to the file format. You can see how these books have their important summary information – the author and the title – on the spine that’s on display when the books are stored on these shelves. That is an important point. I bet even that book that doesn’t have anything on the cover has something on the spine, so you can store them like this. If you had no information on the spine and all the information was on the cover, if you were to find the books on the shelves, you’d have to display them with their covers out. This would be highly inefficient, much less efficient than doing it like this. This is why books have this on the cover, and yes, I do like Stephen King; I think he’s a remarkably good author, actually, and highly underrated.

Marketing and Promotion of Books

Once you get a really famous author, you will generally see that their names on the cover are the big thing because you want to read a Stephen King book – you don’t care what it’s called. When nobody’s heard of you, like Andrew Whitworth’s books don’t have ‘Whitworth’ in big letters on the spine, trust me; because nobody cares about who wrote that book. But these are the different ways that you have of advertising, marketing, and displaying the book.

Rebinding and Preservation of Books

Going back to my 1751 book, there is very little on the cover and spine. This gives you an indication that it has been rebound. Usually, with newer books, you will see pictures on the cover with the names of the author intended to make us want to buy it because we liked their previous work. On this particular book, it comes on what’s called a ‘dust jacket’, which protects the cover of the book by itself; as you can see, it’s getting a little tatty.

The Blurb and Its Function

Paperback books will usually now have information on the back. You call this a blurb or an abstract, and the idea is that you can find out what’s inside the book without paying to go through it, and this makes it look far more useful. So, that’s the outside of the book taken care of now; let’s look inside the book. What can you do with the features of this technology to make the book more useful to you?

The Organisational Devices of Books

For a start, regardless of whether the contents of a book are divided up into chapters, every book is, of course, divided up simply by the fact it has pages. This allows several other ways to make them useful. For a start, the reader can put a bookmark in between two pages, so they know exactly how far they read last time.

You can number the pages – this is very common, and numbering the pages allows you to let the reader know how the book is divided into chapters. You could put a table of contents with page numbers, and you can also let them know where particular subjects are discussed inside a book by including an index.

Not every book needs this kind of arrangement, and sometimes books are arranged differently, as I will show you shortly. You can argue, for instance, that if you do have a novel, the page numbers are essentially irrelevant because it doesn’t really matter what page particular things happen on, but I’m going to get you to think about this kind of thing in the related task – how do your books organize the information within them? There are different ways to organize information.

Dictionaries will do it alphabetically; travel guides like these will organize themselves regionally, both in terms of the whole series and the way the advice within them is divided up region by region in these different countries, so they are organized around a geographical formation. Atlases are arranged geographically; the front of each map shows you exactly how each map relates to the maps on different pages, the information being contained geographically. The atlas is also an example of a book that contains far more than just text.

The Graphic Novel as a Unique Format

This is a very famous graphic novel told mostly by pictures and speech bubbles and also text like that; the book can show a lot of different types of information. There are also certain limits to books. So, of course, the book can never answer your questions if the information within it changes; the book cannot update itself. Remember that idea, right; there are points about all of these different media that apply generally.

Interactive Content in Textbooks

You’ve got this idea you are able to interact with the content of the book in various different ways. Now, some of your books will have things, particularly the textbooks, I imagine, where it says ‘stop and think’. I have done this on Blackboard with you; you go through the Blackboard site, and among the things organized there will be particular points where I’m saying, “Think about this”, okay? Partly it is the equivalent for the distance learners of the things that we’re doing in our class.

[Try writing down a list of the features you find in books which develop their usefulness]

The Limitation of Static Information

As we move on, and you will see this in block three, when I talk about pedagogy, the different types of media that are out there allow or afford different kinds of interactions. As I said here, books are great, but they can’t answer your questions, and if the information changes in them, then you need a second edition. The Alfred Wainwright’s walking guide to the Lake District fells is a very useful book to people like me who like to walk up mountains in the Lake District.

There’s lots of good graphical information and textual information, but things change, and these books were first written in the 1950s and 1960s; what happened in the 2000s – as you can see there – produced a second edition; and you can do this with books. The information was updated and challenged, but the book can’t do this itself. I needed to buy these second editions – it wasn’t like my first edition updated itself.

Conclusion: The Irreplaceable Nature of Books

Nevertheless, as I said at the beginning, there’s far too much information encoded into books and still being published in books for them to go obsolete anytime soon. What I’m going to ask you to do now is think about some books of your own. The book; I hope you realize now, there’s a lot more depth in it, and there are a lot of ways in which the book helps the user navigate around. At the very least, take this lesson forward into any later work that you do.

Application of Learning to Digital Technologies

You will look at Blackboard; you might think Blackboard is easy to get around – you might think it’s difficult to get around. Think about how you might make the information on your team’s channel easier to get around. There are ways in which you can format the information; there are ways in which you can show that, for instance. You’ve got things like a heading – don’t underestimate the simple value of increasing the font size and saying, “Hey, I’ve got a heading.”

The Historical Context of Book Technologies

All of these things have been developing for 1500 years. These are not things that were invented by Bill Gates in 1997. So, a lot of these ways in which our information technologies help us navigate the information that they are providing to us are essential, and that is what makes them useful. Those are the behaviours that they afford.

Look, we’re out of time, but please, I will start a Friday class by looking at some of your learning environment maps, so please post them to Teams by the 20th. There’s no deadline as such, but it would be nice to have a look at them on Friday morning. So, be ready to talk about why – remember you should only be putting things on your maps if you can say why it’s there. If you can’t think why it’s there, don’t map it.

Technology and Politics