Ragged Schools: Growth and Expansion, 1850-1860 by D. H. webster

By 1850, the Ragged School Union had evolved the principles that were to guide it for the next forty years. It had established a successful central organization; it attracted into its service men of the caliber of William Locke, S.R. Stary, and Joseph Gent, who gave unstintingly to the work in hand; it had obtained the services of Lord Ashley, whose active interest promoted the cause of the Union among the wealthy; it had defined its role in relation to a national system of schools. Somewhat optimistically, it observed:

“Ragged Schools are now allowed on all hands, whether it be in the light of philanthropy, patriotism, or Christianity, whether in respect of benevolence, economy, or duty.” (59. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p.7)

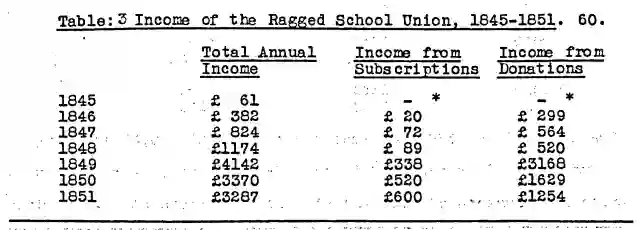

This ignored the opposition to the movement, which was to be both articulate and damaging in the Report of the Newcastle Commission and in the Education Act of 1870. The venture, however, had grown in respect of financial support, as its official statistics show.

(60. Abstracted from Ragged School Union,Annual Reports, 1845 – 1851.)

* No information available.

The sharp rise in income for 1849 was the result of an effort to give wider publicity to the aims of the Union. It launched a Special Appeal, during which ten thousand of its reports and an enclosed letter from Lord Ashley were circularized to clergy, judges, M.P.s, and all the principal merchants and bankers (61. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p.5). A paid secretary and a full-time collector were employed, and the Union started publishing its own magazine.

Its activities were also under scrutiny at the national level with the consideration of Lord Ashley’s motion to Parliament to finance the emigration of suitable ragged school children (62. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, pp. 5,6). By 1860, the Union’s financial situation was sound, and the rise in income during its early growth leveled off.

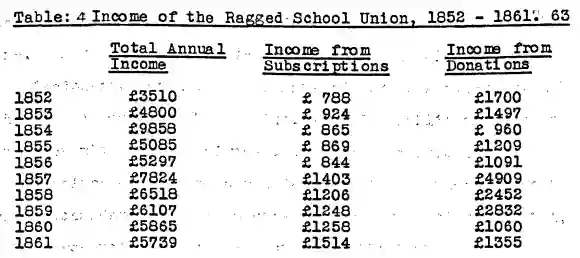

(63. Abstracted from the Ragged School Union Annual Reports, 1852 – 1861)

A legacy of £4,000 inflated the income for 1854, and legacies and bequests formed a substantial part of the income of the Union each year. An unusual feature in the Union’s accounts was that donations were usually well above the annual level of subscription. The reason for this was the attraction which the Union had for the wealthy classes in London. It was through Lord Ashley that the Union was able to approach many who might otherwise have been unaware of its existence. A policy of ensuring that its Advisory Committee comprised leading evangelicals—bishops, M.P.s, lawyers, bankers, and merchants—maintained its access to these classes.

A study of the subscription and donation lists shows that many of the wealthier supporters treated their donation as a subscription, repeating it annually. It also shows that each new appeal not only gained the immediate sums required but succeeded in involving a greater number in the financial support of the Union. The appeal of 1857 added £3,500 to the annual income. A plea by Lord Ashley was printed and circulated to 40,000 Londoners, including “the entire Red Book names and all of the bankers and City merchants” (64. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1857, p.16).

The public meeting in conjunction with the appeal was chaired by the Lord Mayor. The policy of the Union was to husband its finances, and it invested considerable sums to create a reserve pool of capital, though it was not until the end of the 1870s that it required to draw on this. Interest from investments, profit from the magazines and other publications, as well as rent from buildings held by the Union formed that part, of the annual income not covered by subscriptions, donations and legacies.

If the principles of action for the Union were clear in 1850, so was the enormity of the problem. Despite constant self-congratulation and “thankfulness to God” for what had been achieved, it never rested on its gains but continually sought new ways to serve. After its rapid rise to prominence and with all of the promise of early success, the committee members still:

“…lamented the comparative inefficiency of all that they have yet been able to accomplish. They have constantly regretted that the schools could not be provided with paid teachers and industrial classes. They have often mourned after the still limited number of voluntary teachers and the laxity of discipline that has resulted from it. They have regretted the migratory and vicious habits of the children, whereby all moral influence is, in so many cases, rendered nugatory” (65. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1850, p.6).

These problems remained until the early 1870s when the actions of the London School Board resolved them. Three important areas in the Union’s activities emerge in the decade from 1850 to 1860: the increase in the number of schools and scholars, teachers, and volunteers; the attempt to sustain an annual emigration of ragged pupils from the schools; and the proliferation of a wide variety of auxiliary and missionary enterprises.

Firstly, the success of the ragged schools created a serious difficulty for the Union, which it never satisfactorily resolved. Its own workers quickly realized that the schools were “getting above their level.” (66. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p.7) A recommendation to employ a paid officer in each district to check the homes of the children and the parental income; though affected, this could not be expected to solve the basic problem brought about by the improvement of the children: “What to do with such improved children puzzles your Committee and perplexes the committees of almost every ragged school in London” (67. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p.8).

Once turned away, they did not doubt that “the children will be cone ragged again and as depraved as ever,” so “until some alternative asylum be found for them, the Committee see no alternative but letting them be where they are” (68. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p.8). The purely theoretical solution which saw the ragged school “as a moral cleansing agent or filtering machine, not retaining the improved and purified particles, but passing them off in order to make room for fresh impurity” (69. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1852, p.14) was impossible.

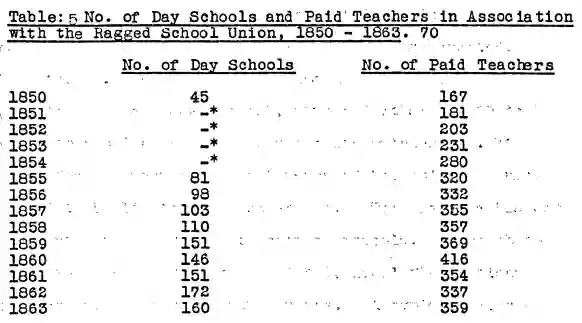

The idea was imprisoned in its own metaphor. The stark fact was that there were no schools to which the children could be transferred. The problem arose in the day schools; the evening schools took older children who usually attempted some work during the day. These schools had increased with the growth of the movement and became of major importance in the educational and missionary work of the Union

(70. Abstracted from Ragged School Union Annual Reports and Minute Books, 1850 – 1863)

* Figures not available.

The peak of this growth was attained in 1866, when the schools numbered 204 (71. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1866, p.9). Thereafter, a decline, accelerated by the creation of Board Schools and the diminution of interest in this side of the work, is evident. The day school was rarely purpose-built. Looking back on the first forty years of the movement, it was felt that “It would have been a wiser economy if in the past more money had been spent on structural conveniences” (72. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.8).

However, the fact that the early workers were thankful for “The tumbledown tenement, the adapted cottage, the improved workshop, the reformed hayloft, the whilom skittle ground, the covered back garden, the converted beer shop, or the translated penny gaff” was put down to their desire to act promptly and not wait for model buildings or perfect contrivances (73. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p.8).

In a few places, freeholds were secured and substantial buildings erected. At Lambeth, Mr. Henry Beaufroy, a local distiller, left £10,000 to build a ragged school, with a further £4,000 to be invested to provide an annual sum for its maintenance (74. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p.16). However, for the most part, the tenancy of the buildings used was found to be limited and precarious.

This meant a history of frequent change for the majority of schools. Even where premises were satisfactorily negotiated, local fluctuations in numbers and teachers prompted moves. A typical example was Field Lane, one of the earliest and most famous ragged schools. It commenced in November 1841, when Mr. Provan, the City Missioner, crowded forty-five children into a small back room in Caroline Court. After a few weeks, he moved it to a lane called White’s Yard. The hostility of the neighbors forced a move to the upper floor of the same house after a short time.

The first anniversary of the school was celebrated in 1842, when the school occupied No. 65 West Street, West Smithfield. Mr. Provan had seven voluntary teachers by this time and, for the increased numbers of children attending, he eventually rented further rooms at the same address. The cost of the rent was three shillings per week. Continued expansion brought a search for new premises, and in 1844, the school took up large premises on the corner of West Street.

KING EDWARD RAGGED SCHOOLS,

KING EDWARD STREET,

SPITALFIELDS.

Source: London Borough of Tower Hamlets Public Library.

The rent of £35 p.a. was partially defrayed by an annual grant of £15 from the Ragged School Union, a twenty-year period of growth and consolidation of activities took place at these premises. However, the construction of the approach road to the new Smithfield meat market involved the demolition of the school. It re-established itself at Hatten Wall, Saffron Hill, in 1866. By 1877, it was in Wilderness Row, Aldersgate, occupying temporary classrooms due to the vacation of its premises to make way for the new Clerkenwell Road. It finally settled at Vine Hill in 1878 (75. Field Lane Institutions, The Field Lane Story, 1961, Chaps. 1-5).

The day schools had paid teachers assisted by paid monitors and voluntary helpers. The movement boasted that its teachers were among the finest in the country, but the Union’s criteria were concerned with missionary zeal, a personal religious experience, and moral uprightness. By other standards, the paid teachers were usually unqualified, poorly educated, and unable to command a very high salary. The view of those outside of the movement was that the paid day ragged school teacher was of a similar standing to the workhouse teacher of pauper children, which was notoriously low. Edward Twisleton, Assistant Poor Law Commissioner in Norwich, expressed the prevailing opinion.

“Nothing can be more lamentable than the low notions and groveling conceptions which prevail respecting what a good schoolmaster ought to be… Their ignorance is often of the grossest kind, although easily accounted for by their former modes of life. Many of these are persons who have failed in business and who think that, as a last resource, they may turn schoolmasters without previous practice… And such persons are sometimes elected, partly from a feeling of compassion and partly from an idea that there cannot be any great difficulty in teaching pauper children to read, write, and cipher.” (76. Report from the Poor Law Commissioners on the Training of Pauper Children, 1841, Appendix 8)

Within the Union, it was felt that fully qualified teachers would over-emphasize the intellectual aspects of the children’s education to the detriment of the moral and religious parts. Mrs. Cornwallis recommended “a six months” training on our system of mercy and patience” (77. C.F. Cornwallis, A Philosophy of Ragged Schools, 1051, p.66). She probably spoke for the movement when she defined the successful teacher as the person who exemplified in his manners “the law of love” and “won the hearts” of the children by “showing that what they teach to others they themselves believe also” (78. Ibid., p.85).

The Union remained sanguine on the matter of its teachers, though it offered what help it could. It employed school agents to visit the schools, examine the children, and advise the personnel. Their reports were rarely critical and offered little insight into the nature of the schools’ problems. A “Paid Teachers Association” was formed “for conference and mutual improvement,” and its existence was noted regularly in the annual reports (79. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1859, p.13).

However, the H.M.I.s implementing the Education Act applied standards which few of the day-teachers in the ragged schools could meet. That many of the men and women were devoted and bravely faced daunting conditions and circumstances is evident from the magazines of the Union as well as the Reports of Her Majesty’s Inspectors. Whether they…

Received their salary (in practice, £75 for a man, £45 for a woman) for being a teacher or for being an evangelist was a question easily answered by even the most sympathetic H.II.I. The force of paid teachers—just over four hundred at its peak—declined after 1870 with the reduction in the number of day schools.

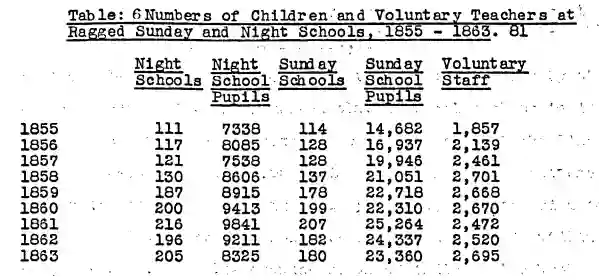

The voluntary workers occasionally attended to teach during the day but more usually in the evenings and on Sundays. They were regarded as “the very crown of the Ragged School System” (80. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1872, p.7) but remained in short supply. At first sight, it is difficult to understand the annual pleas for more staff, for the increase in schools of whatever character was usually paralleled by a proportionate increase in voluntary workers. The numbers quoted would appear to give an adequate force (given the standards of the Union).

(81. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1855 – 1863)

The problem was the erratic attendance of the volunteers. The Union found that “there is never above one third of the number present at any one time” (82. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1859, p.7). It was “next to an impossibility to get more voluntary agents,” despite the fact that they believed there were as many ragged children waiting to enter their schools as they already had (83. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1863, p.6). In desperation, it attempted to induce the wealthier suburban churches “to render direct aid by working some ragged school as a branch of that church” (84. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1865, p.8). There was no response to this appeal.

It was quickly realized that the calls of the day schools on the volunteers would have to be limited. The Union adopted the device of paid monitors to relieve the pressure on the teachers: “Though in many cases quite young, they were found equal to the task of teaching and controlling younger children in the Day and Infant Schools” (85. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1864, p.6).

Half of the cost to the schools of this system was met by the central body. They recommended that a school with up to 100 pupils would require 4 monitors who would receive 2 shillings each per week; one with 100 to 150 pupils needed 6 monitors who would receive 4 shillings each per week; any school above 150 was held to warrant 8 monitors at a payment of 6 shillings each per week (86. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1866, p.13). The account books of individual schools show

that few got more than a shilling a week and most between twopence and sixpence a week. They had appeared in individual ragged schools by 1850 but were not officially recognized by the Union for grant purposes until 1854. By 1858, it was reckoned that there were 200 paid monitors, and this rose steadily (87. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1856, p. 6). In 1859, there were 371 (88. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p. 4); in 1864, there were 450 (89. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p. 4); and on the eve of the new Education Act, they numbered 581 (90. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p. 4).

The H.M.I.s who visited the ragged schools were agreed in their condemnation of the system of monitors. They found them wholly ignorant, far too young, and often without any temperament or inclination for the job they were attempting. It was a practice opposed by British and National schools, as they occasionally found some of their brighter pupils leaving to take up these posts.

The second major development in the decade from 1850 to 1860 was the attempt to sustain the emigration of the ragged school pupils. Annual reports, the Union’s magazine, and the children’s magazine all gave prominence to this venture, which the actual numbers of children involved barely justified. Lord Ashley’s request to Parliament to finance the scheme for one year was granted in October 1848 (91. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p. 6).

Frontispiece of the Ragged School Union Magazine

Source: The Shaftesbury Society

The Union attempted to reap the maximum publicity from this and included the emigrants as examples in its standard arguments to prove that “prevention was…better than cure’: “A school better than a prison – a ragged teacher better than a policeman – ragged school emigrants better than government convicts – youthful training more pleasing and hopeful than adult reformation.” (92. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1801, p.7)

150 children were finally selected in the first year, 134 boys and 16 girls out of a total of 276 applicants. (93. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p.6) From the outset, the scheme was regarded as an opportunity, a change to be eagerly grasped by children whose employment prospects at home at that time were not good: “Mere destitution is not to form a qualification for this privilege. It is available to those who have given evidence of reformation of character and a certain amount of attainments.” (94. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1849, p.27)

It was hoped that at least a hundred children could be sent each year: “This will be at the rate of one to each school and may be regarded as a well-earned prize.” (95. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p.10) The children who were selected were required to be in good health and to have attended the ragged school regularly for six months.

Each applicant underwent a careful examination… first by the officers of the Union and then by the Emigration Commissioners. (96. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1849. p.27) They repeated the Lord’s Prayer and Ten Commandments, worked the four rules of arithmetic, wrote from dictation, read a passage aloud, and produced a certificate confirming an attendance of at least four months in an industrial class.

The Union found it necessary to be quite explicit regarding its methods and criteria of selection. Critics were sceptical of the schools’ ability to pick out the cost-deserving cases and emphasized the short duration of “ragged education” (97. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1849, p.27). Some wondered if the children were really being transported. The Union was firm that “all emigrants left of their own free will and pleasure” (98. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p.7). All received parental consent.

The first group to emigrate represented thirty schools. The most successful in gaining places for their pupils were Street Ham Street, which sent 18 children; Grotto Passage, which sent 11; and Agar Town and Yeates Court, which sent 12 each (99. Ragged-School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p.7). Each of the children received a Bible “with marginal references” and numerous tracts, as well as a new outfit of clothes. The Union hoped that the Government would “repeat the boon … in succeeding years” (100. Ragged School Union,”Annual Report, 1849, p.7).

When a second grant was not forthcoming in the next year, it was faced with the task of organizing a public appeal and creating a fund to finance the passage of the ragged scholars. It raised £1,129 and sent twenty-seven boys to Australia and, at the time of printing the Annual Report for 1850, had paid for eleven more who were simply “waiting for a ship” (101. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1850, p.9).

Faced with a very heavy burden of expenditure on emigration, if they were to sustain the initial numbers, the Union offered fewer places and managed to make some economies. It was able to reduce the fare to Australia from £20 to £15 by sending the children from Liverpool rather than London and obtained third-class transport for them on the North Western Railway at half the normal fare (102. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p.10).

By 1852, the number stood at fifty-four—thirty-seven children had gone to Australia and seventeen to America—but it was clear that this outlet was not going to provide the panacea hoped for. It was suggested that perhaps “…many would find places at home if they had something in hand as a testimony of their good character” (103. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1852, p.12).

However, the Union never changed its opinion that government aid for the emigrants was proper and necessary. When their own Emigration Fund was exhausted in 1853, they sent a delegation headed by Lord Ashley to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Sir John Pakington, to appeal for assistance. He was unable to do anything for them and suggested that they were misinformed about the true extent of the “labour shortage” in Australia. What, in fact, worried the supporters of the movement more was the discovery of gold there and the widespread publicity given to an adverse report from the Governor of Melbourne, Mr. Latrobe, on the depraved character of emigrants (104. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p.10).

Thrown back on their friends and supporters again, the Union resolved that what money it could raise would be best spent in sending children to Canada. It sent twenty in 1854. Unfortunately, eleven were shipwrecked, and only two were saved. By 1856, its funds were again exhausted, and it was able to send only fifteen children. It noted that the urgency for the scheme had decreased in view of a better economic position in London and the opportunities in the army created by the war (105. Ragged School Union, Annual Report,1856, p.7).

The majority of children to emigrate were boys. Then it was decided to send girls to Canada as domestic servants; the Union had fears that the venture would be misunderstood in view of the dangers many of them had faced in their early years. It resolved the issue by sending Mrs. Edwards, Matron of St. Giles’ Refuge, with the children to ensure that they got good positions (106. Ragged School Union, Annual Report,1857, p.10). By 1860, only a trickle of emigrants could be financed, and the whole episode quietly slipped into the background in Minute Books, Magazines, and Reports.

After 1865, the Union did not even bother to give the total numbers sent abroad. It commented that emigration was “considerably reduced” because employment at home was better and there was some fear that Canada might be unsafe in view of the proximity of the Civil War to her (107. Ragged School Union, Annual Report,1865, p.21). Thus, the unctuous tone adopted by the Movement about its emigrant children was changed after 1860. As usual, it had claimed too much for too little. Inflated claims, even when supported by countless letters from ragged emigrants who had “made good,” could not disguise the fact that emigration was an answer—however good—to the wrong question.

The third area of major activity for the Union in the decade 1850 – 1860 was in the auxiliary services and organizations which developed from its experience of the difficulties of the ragged families. Agencies, societies, and associations were formed to alleviate the problems associated with their physical condition, moral state, and industrial incapacity. By 1853, it had proliferated to include operations connected with refuges and dormitories, shoeblacks, mothers’ meetings, penny banks, crossing sweepers, reading rooms, and industrial classes (108. Ragged School Union, Annual Report,1855, p.5). The most significant were those for shoeblacks and the refuges and dormitories.

The Ragged School Shoe-Black Society was established in 1851 “to give employment to deserving boys in connection with the Ragged School Union” (109. Report on the Metropolitan Reformatories and Refuges, 1856, p.15). It offered its privileges to boys who have shown evidence of reformation or whose destitute condition precludes them from obtaining other employment (110. Ibid., p.15). Coming to public notice at the Great Exhibition, it was a very popular institution. Although not intended as more than a “temporary livelihood,” it was successful to the degree that it enabled children to save considerable sums “as an introduction to permanent situations” (111. Ibid., p.15).

Indeed, the amounts earned became a regular feature of the Ragged School Magazine and appeared until the 1880s. “The earnings of each boy were disposed of as follows: sixpence was returned to the boy as his allowance, and the remainder was divided into three parts, of which the first was paid to the boy, the second was put into a fund called the “boys’ bank,” to be employed for his future benefit, and the third was appropriated by the Society” (112. Ibid., p. 30. [The total annual sum involved can be seen from the Accounts for 1856 of the South London Shoe Black Society. The total earned was £468. Of this, £292 was paid to the boys, £89 put into the ‘boys’ banks’, and the Society took £86 towards its expenses, which totaled £157 p.a. There were 35 boys in the Society that year.]).

The boys were expected to report to the Society’s offices at 7 a.m. for prayers and Scripture reading and return at 6:30 in the evening “to account for their day’s earnings” (113. Ibid., p. 30). Attendance at weeknight ragged schools was encouraged and was compulsory at the Sunday schools. The first Society—called the Central Reds because of the red jersey worn by the boys—was followed in 1854 by two others in the East—the Blues—and the South—the Yellows.

In 1857, the North Western, the West Kent, the West London, the South Suburban, the Islington, and the Kensington Societies were formed. All had their distinctive uniforms made by the girls in the ragged schools or refuges. They also made their boxes and hats. Whether the Societies achieved their major purpose of “qualifying the children by suitable training for respectable situations in afterlife” is open to question (114. Ibid., p. 31). The evidence used by the Union to justify the whole operation was financial and comprised totals earned per annum. This simply pointed to its value as a short-term employment agency.

The sort of evidence required relates to the position obtained by the children after serving in the ‘Shoe-Black Brigade’. It is not usually available in the detail needed. In the first five years of the Central Bed Society, one of the largest, 451 boys were employed: “of whom 83 have been provided with situations, 25 have emigrated, 6 have entered the army and navy, 2 have died, 58 remain within the Society, and the rest have either left of their own accord for other employment or have been sent away for incompetence or discharged for bad conduct” (115. Ibid. p.15).

When some clear figures are given of the number failing to obtain positions, the proportion seems high. Thus, in 1855-6, the East London Society lost 43 boys: “23 obtained for themselves situations—their good conduct on their stations having been noticed by their present employers; 6 have left on their own account, and we do not know what has become of them; 17 have been dismissed for dishonesty or general bad conduct” (116. Ibid. p.30).

The popularity of shoe-black societies as provisional employment agencies prompted similar efforts. The Union and its schools attempted to organize ‘broomers’—boys employed during the winter to clear the fronts of shops; ‘steppers’—girls to scrub and wash the outside steps of houses; ‘messengers’—children who would take parcels up to the value of £3 from one part of the City to another; ‘sweepers’—boys who could clean the roads and clear the crossings; ‘house-boy brigades’—boys employed to undertake unskilled laboring work in and around the house.

CROSSING SWEEPERS

FROM: H. MAYHEW, ‘LONDON LABOUR AND LONDON POOR’, 1860.

Their success was limited and the difficulties of properly supervising street occupations, together with the temptations such occupations placed before the children, led to their gradual abandonment. The zeal and devoted efforts of the members of the Union in this work were very great. The failure to attain their object for the poor children by these schemes was confessed in the attempt to devise further and different means of reaching it. The sincerity and sacrifice of the volunteers did not change the basic economic and social difficulties from which the appalling condition of the ‘ragged’ poor derived.

The Union expressed its concern particularly for those children who had no homes and were forced to sleep in common lodging houses or wherever shelter could be had in the open. Their plight prompted some of the ragged schools to make dormitory space available. Others instituted their own refuges in association with the schools. Some members of the movement established general refuges to which any young persons could be admitted. In 1852, nine refuges were attached to the Ragged School Union.

By 1856, the figure had reached sixteen, and there was no further increase. In that year, the Reformatory and Refuge Union was organized, with Lord Shaftesbury as President. The Ragged School Union had feared that interest and funds were being diverted from the educational work to the refuges and suggested a new organization to deal specifically with this problem. The new body was able to expand into reformatory refuges and institutions for the adult as well as the juvenile destitute. It retained strong links with the parent Union until 1868, when it became independent, and gave generously towards the support

Conditions within the refuges were spartan. Grotto Passage Ragged School and Refuge for Restitute Boys stated: “The food has, of course, been very plain and sometimes scanty, prepared by the boys themselves in turn under proper supervision. A cottagers’ stove has been the only cooking apparatus… The boys sleep in hammocks… The average residence in the institution is twelve months; the greater part are orphans” (117. Ibid, p. 6).

Opportunities for boys were scarce. “Much trouble has been experienced in finding employment in London for the boys when prepared for situations; this arises from the reluctance of employers to take boys from such institutions. All experience points to the navy or the Colonies as the only outlets for this class” (118. Ibid, p. 6).

Nevertheless, the Union enabled children to have shelter and food in circumstances when they would otherwise have had neither. That it increased their chances of obtaining suitable employment is less certain. Refuges taking girls to train as domestic servants probably had more success than others.

The Royal Commission appointed to “enquire into the state of popular education” reported in 1861. Part of its report dealt with the desirability of encouraging and financing the ragged schools (119. Report of the Royal Commission to Inquire into the State of Popular Education in England, 1861, Part III: The Education of Vagrants and Criminals – Parliamentary Papers, Vol. 21, Part 1).

It was crucial because it formulated the attitude of the government which was to remain until the new Education Act. Mr. Lingren, the Secretary to the Committee of Council, expressed his opinion that “Ragged Schools are to be regarded as provisional institutions which are constantly tending to become elementary schools of the ordinary kind or industrial schools certified under Act of Parliament” (120. Parliamentary Papers, Vol. 21, p. 394).

The commissioners took their view from him and reported that the present policy “is wise and should be maintained. In order to entitle any class of institution to receive aid from the grant administered by the Committee of Council, it is indispensable that they should be shown to be likely to produce valuable permanent results, but this is not the case with ragged schools.

The influence which they exercise over children who would be otherwise destitute of any education whatever is probably beneficial, though there is reason to fear that little can be effected by the very limited instruction of children who are accustomed to vicious homes and parents. The only efficient mode of reforming such children is to subject them to the strict discipline of an industrial school.

The slight influence for a very limited class is the only advantage produced by the establishment of separate ragged schools. It appears to be overbalanced by the disadvantage that such schools withdraw from the ordinary day schools a considerable number of children who would otherwise be sent there either by their parents or by the guardians of the poor, and this is a serious evil.

A further objection to affording public assistance is that strict general rules rigidly adhered to are absolutely necessary in the administration of public money. To obtain grants, attaining a certain degree of discipline, the payment of certain fees by the parents, and the prospect of a certain degree of permanence in the schools are necessary. If, by neglecting these considerations, a school might qualify itself for special grants as a ragged school, there can be little doubt that the standard of efficiency in day schools would be gradually and certainly lowered.

For these reasons, we think that ragged schools in which industrial instruction is not given, though they may in some special cases be useful, are not proper subjects for public assistance” (121. Ibid., pp.395 – 395). The evidence points to the fact that the commissioners did not consider the case of ragged schools at any length or fairly. It purported to reach its decisions after considering the evidence of Patrick Cumin, one of the assistant commissioners, and Mary Carpenter, who had been the prime force in initiating ragged schools in Bristol.

The evidence of Cumin looked impressive and was based on a statistical survey of ragged schools in Bristol and Plymouth. By the side of it, Miss Carpenter’s evidence was too subjective, prone to the criticism that it generalized from specific cases and was rather sentimental. Cumin’s survey established, to the satisfaction of the critics of the ragged schools, that a ragged class did not exist. By this was meant a group who, not being outdoor paupers, could not afford to pay for their children at the ordinary day school. He skilfully compared the occupations of parents in National, British, and Ragged Schools and found no differences.

The only distinguishing feature of the parents of the ragged school children “consists not in their occupations, nor in their poverty, but in their moral character” (122. Ibid., p.340). It was deftly done and raised the question of whether or not the rest of society was to be chargeable because dissolute parents would use “1d. for gin rather than school” (123. Ibid., p.390). He even questioned the continual boast of the ragged school supporters that their institutions reduced crime and delinquency in the young.

“If education has any effect in checking crime, it seems not to be through the ragged schools but through the ordinary day schools and the reformatory schools” (124. Ibid., p.392). Miss Carpenter could not rebut the charges made by Cumin. To some extent, it was a masterstroke on his part to use figures from the Bristol schools, for she had nothing comparable to offer save her own opinion of these same institutions.

The commissioners were hardly likely “to be impressed by her suggestion that they visit the homes of the ragged parents to ascertain whether or not they formed a separate class.” Her desire for “a great change in the social condition of our country” and her determination to plead for it took her argument beyond the brief of the Commission (125. Ibid., p.392). The tenor of her evidence and its quality as sustained argument was reduced and finally collapsed when she resorted to eight case studies—the sort of things which appeared in their hundreds in annual reports up and down the country. The Committee receiving her report dismissed it curtly in a couple of sentences:

“But such families appear to contribute a small portion of the ragged school scholars. The bulk of the scholars appear to be the children of outdoor paupers or of persons who can send their children to paying schools and would do so if there were no ragged schools” (126. Ibid., p.392).

No proper investigation was made into the case for ragged schools. Cumin’s report, though politically astute, had not considered the major areas of ragged school development—London, Liverpool, and Manchester. To argue from examples of very limited numbers of schools in unrepresentative areas to a rational pattern was inexcusable. Even in its details, his work was defective. In the contrast he made between the occupations of parents in the various schools, he omitted to ask the single important question which could possibly have upset all his evidence: the question of the seasonal nature of the employment.

The evidence from the schools points to this as the crucial economic factor in the poverty of the children’s parents. By 1861, Mary Carpenter’s enthusiasm for ragged schools had waned. Her interest was centred on reformatory education, and the London Union, despite their respect for her efforts, would never have admitted that she was their advocate.

It must be doubted whether the possibility of ragged schools receiving government grants was ever seriously entertained by the commissioners. Although provincial schools had requested aid in the early 1850s, the London Union had set itself firmly against this, suspecting that in its wake would come government controls. It maintained its position vociferously during the period up to 1860, and its intransigent attitude no doubt accounted for the fact that none of its members was asked to submit reports to the Commission.

From the government side, it would have been unwise to attempt to force grants on unwilling recipients, particularly as the Commission rightly saw that the problems of establishing workable criteria for their award were very difficult. More directly, it could introduce a further variation on the religious problems bedevilling the attempts to set up a national educational system. The schools were plainly religious, openly missionary, and covertly Protestant in character, but they were also unsectarian, comprising the spectrum of non-Roman Catholic groups among their organizers. That the ragged movement could resolve the tensions that existed between the established church and the dissenting groups

At a national level, the government found it implausible. Thus, the Commission, deaf to the slogan-choked arguments of the activists and acting more from political expediency than from a rational assessment, trivialized the matter. It did not bother to collect suitable statistics, and even those which were given were incorrect (127. Ibid., p. 3. It stated that the Ragged School Union was founded in 1654; it should have been 1844. It gave its income for 1859 as £5,142; it was £6,107. It said that in 1859 there were 192 week-day ragged schools in London; there were 151. It gave the total number of children in the schools in London as 20,909; there were nearly 30,000 of them, in fact).

Initially, the Ragged School Union was almost stupefied at the banality of the Commission’s treatment of their work and problems. Not realizing that its own previous positions were responsible for much of this, it allowed itself the luxury of moral indignation. The minutes of the Central Management Committee in the period 1861 to 1863 are replete with a virulent bitterness of attitude at what they took to be a deliberate misunderstanding of their work or a grossly incompetent assessment of it. It asserted its basic principle of missionary endeavor.

The schools did not prize “mere educational proficiency, book learning, or high mental attainments”; instead, they aimed to induce “Godly sincerity, decided Christian conduct, and a sincere profession of Bible truth” (128. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p. 6). Then, it accused the Commission of making no examination of the London schools and of ignoring the value of its auxiliary enterprises. Lord Shaftesbury, acting the part of Savonarola in a faithless age

And with eloquent invective, pronounced the report anathema. He in the Lords and the Hon. Arthur Kinneard and Sir Stafford Northcote in the Commons introduced a motion: “To inquire how the education of destitute and neglected children may be cost-efficiently and economically assisted by public funds.” A Select Committee was set up. (129. Ragged School Union. Annual Report, 1862, p. 5)

Its members were sympathetic to the movement, and they found that the Royal Commission’s views were at variance with evidence of the facts. It purported to find a ragged class and praised the organization, zeal, discretion, patience, faith, and constitutions of the ragged school volunteers. Its final recommendation was that “ragged schools should be left to the missionary exertions of the ragged school managers, without any interference by the government.” (130. Ragged School Union. Annual Report, 1662, p. 7)

Its purpose, to re-establish the work as reputable and necessary, and the Ragged School Movement as an appropriate instrument for it, was achieved. The Union naturally supported the findings and held that “those engaged in ragged work in London were costly averse to government aid for fear that government grants would bring government interference and deaden the voluntary religious character of the work”. (131. Ragged School Union. Annual Report, 1862, p. 6)

The next ten years were to bring increasing pressure on the Movement’s day schools and challenge its character at its most fundamental points. That “success does not depend upon regular inspection and certified teachers or upon money grants from the state, or upon any amount of school machinery or educational appliances, but upon loving, faithful, and earnest workers, upon zealous teachers of Bible truth.” (132. Ragged School Union. Annual Report, 1866, p. 12) was not self evident to those outside the narrow confines of evangelical philanthropy.

Listed Bibliography of References:

59. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p. 7.

60. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1845 – 1851.

61. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p. 5.

62. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, pp. 5, 6.

63. Abstracted from the Ragged School Union Annual Reports, 1852 – 1861.

64. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1857, p. 16.

65. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1850, p. 6.

66. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p. 7.

67. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p. 8.

68. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p. 8.

69. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1852, p. 14.

70. Abstracted from Ragged School Union Annual Reports and Minute Books, 1850 – 1863.

71. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1866, p. 9.

72. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p. 8.

73. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1884, p. 8.

74. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p. 16.

75. Field Lane Institutions, The Field Lane Story, 1961, Chaps. 1-5.

76. Report from the Poor Law Commissioners on the Training of Pauper Children, 1841, Appendix 8.

77. C.F. Cornwallis, A Philosophy of Ragged Schools, 1051, p. 66.

78. Ibid., p. 85.

79. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1859, p. 13.

80. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1872, p. 7.

81. Abstracted from Ragged School Union, Annual Reports, 1855 – 1863.

82. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1859, p. 7.

83. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1863, p. 6.

84. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1865, p. 8.

85. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1864, p. 6.

86. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1866, p. 13.

87. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1856, p. 6.

88. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p. 4.

89. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p. 4.

90. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1869, p. 4.

91. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p. 6.

92. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1801, p. 7.

93. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p. 6.

94. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1849, p. 27.

95. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p. 10.

96. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1849, p. 27.

97. Ragged School Union Magazine, 1849, p. 27.

98. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p. 7.

99. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p. 7.

100. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1849, p. 7.

101. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1850, p. 9.

102. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p. 10.

103. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1852, p. 12.

104. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1853, p. 10.

105. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1856, p. 7.

106. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1857, p. 10.

107. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1865, p. 21.

108. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1855, p. 5.

109. Report on the Metropolitan Reformatories and Refuges, 1856, p. 15.

110. Ibid., p. 15.

111. Ibid., p. 15.

112. Ibid., p. 30. [The total annual sum involved can be seen from the Accounts for 1856 of the South London Shoe Black Society. The total earned was £468. Of this, £292 was paid to the boys, £89 put into the ‘boys’ banks,’ and the Society took £86 towards its expenses, which totaled £157 p.a. There were 35 boys in the Society that year.]

113. Ibid., p. 30.

114. Ibid., p. 31.

115. Ibid., p. 15.

116. Ibid., p. 30.

117. Ibid., p. 6.

118. Ibid., p. 6.

119. Report of the Royal Commission to Inquire into the State of Popular Education in England, 1861, Part III: The Education of Vagrants and Criminals (Parliamentary Papers, Vol. 21, Part 1).

120. Parliamentary Papers, Vol. 21, p. 394.

121. Ibid., pp. 395 – 395.

122. Ibid., p. 340.

123. Ibid., p. 390.

124. Ibid., p. 392.

125. Ibid., p. 392.

126. Ibid., p. 392.

127. Ibid., p. 3. It stated that the Ragged School Union was founded in 1654; it should have been 1844. It gave its income for 1859 as £5,142; it was £6,107. It said that in 1859 there were 192 weekday ragged schools in London; there were 151. It gave the total number of children in the schools in London as 20,909; there were nearly 30,000 of them, in fact.

128. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1851, p. 6.

129. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1862, p. 5.

130. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1662, p. 7.

131. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1862, p. 6.

132. Ragged School Union, Annual Report, 1866, p. 12.

This is the work of D.H. Webster who wrote a thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Leicester, 1973. It remains an important historical document and analysis of the Ragged School and free education movement in Britain. It will be reproduced and published verbatim in instalments for educational purposes to facilitate review and discussion about education. This post is the first part of section one of the thesis where the references have been reproduced inline within the text.

You can see the thesis overview and contents here:

The Ragged School Movement and the Education of the Poor in the Nineteenth Century