The Waifs of England and Their Contribution to Nineteenth Century Social Reform by Katharine F. Lenroot

For the most part, history has been concerned with great economic, social, and political movements and the men who were involved in them. Only rarely has it portrayed the plight of ragged, hungry, even homeless and abandoned children. Indeed, until recently, and to some degree today, the welfare of children has been on the fringes of public policy.

Is it not a paradox, then, for an author to present a work wherein the poorest, most neglected, most forlorn children, and those who were vagrants, petty thieves, and juvenile delinquents, are the chief protagonists and to claim their story merits important consideration in the history of England in the last century?

And if we do grant this story its historical significance, does it have any pertinency for the problems and perplexities of our own nation and our own time in respect to the young? It is the belief of this writer that these questions can be answered in the affirmative and that the account of what was done more than a hundred years ago in behalf of the most unfortunate among Britain’s children does have relevance for us today. The aim of ‘Sixty Years in Waifdom’ was to show what share the ragged school movement had in English national history and to indicate the high value of the principles upon which, with changed forms of activity, it continued its work into the twentieth century.

In writing his history, Montague strove also to expose some of the crying social needs of London in his own time. The scope of the work is large. The author begins with a discussion of the class differences and social problems of England in 1844, noting some of the prominent reformers of the century and describing the early ragged schools and the scholars who attended them.

Then the teachers are discussed: their motivations, the conditions of their work, the broader undertakings to which their experiences led them, and their devotion to the schools. Much of the latter portion of the book is concerned with the development of the national body, the “Ragged School Union.” The Ragged School Union was organized in 1844 to “give permanence, regularity, and vigor to existing Ragged Schools, and to promote the formation of new ones throughout the metropolis.”

With Lord Shaftesbury as its President for some forty years, the influence of the Union spread throughout Great Britain. It may seem difficult today to believe that thousands of volunteer teachers, having little or no training and working under minimum supervision in surroundings and conditions totally alien to an educator’s concept of a proper environment, could have achieved the notable results portrayed in the book.

The harm that might result from a school so rudimentarily put together was recognized by some of the most devoted participants in the movement and used in support of pleas for more extensive financial resources, materials, equipment, and teachers. Mary Carpenter, a ragged school teacher herself and an outstanding pioneer in the reform movement for the treatment of juvenile delinquents, stated in her book *Reformatory Schools*, published in 1851:

“The only organized movement that has been made in the present century to carry education to the lowest depths of society, to seek out in their hiding places the most wretched and deserted children, to shed over them the light of knowledge and of Christianity, and thus, if possible, to raise them from their hopeless condition, has been made by the promoters of Ragged Schools….”

She, too, was concerned to point out the errors into which the schools had fallen, to show what they could do and what was beyond their scope and power. As amazed as one might be at the miserable plight of the waifs of London in the 1840s, so, too, might one marvel at the devotion and Christian love given in their behalf and to them, by persons from the most humble to the most privileged circumstances. It is of interest to note here that a similar movement was shaping itself in New York under the guidance of Charles Loring Brace.

As the first executive officer of the Children’s Aid Society of New York, Brace devoted his life to the thousands of homeless and outcast children of the city, animated by the same motive of Christian love as his London colleagues, and using means of reaching the children strikingly similar to those employed by the Ragged School Union.

Parallels can be found also in both the problems and the attempts to ameliorate or solve them, not only with nineteenth-century New York, but also with contemporary America. Poverty, ignorance, and discontent are now, as then, elements for concern. What is the purpose of the so-called outreach aspects of the Anti-Poverty Program and many of our social agencies but to find and help the most needy or forgotten among our people, especially the young?

Our concern with the alarming extent of juvenile delinquency and serious crime matches in some degree their anxiety about the children of the “perishing and dangerous classes” and the juvenile offenders. The ragged school movement itself grew out of a conviction of the importance of education, both secular and religious, for children too poor to pay the prevailing school fees and too ragged, too unprepared, too much depended upon as earners of their own or part of their family’s meager livelihood, too accustomed to street life, to make attendance at the usual day schools feasible or suited to their needs.

In our time and country, the emphasis is upon the value of education as a means of preparing children to meet the challenges and opportunities of our highly mechanized and complex world, and the problems are those of adaptation of educational programs and methods, in schools open to all, to children differing widely in home and community backgrounds and experiences. A study of the earlier programs as worked out in England more than a century ago can teach us something.

Of special interest was the involvement in a single cause of all classes of society, including those coming from the same surroundings as the children served, and the readiness with which the volunteer worked next to the paid teacher. We note, also, the unanticipated diversification of the program, as the years passed, into widely differentiated services yet always with continuing insistence upon keeping them close to the most needy, and the development of understanding and commitment to common purposes among the most elevated, the most representative, and the poor of England.

The Setting of the Ragged School Movement

‘Sixty Years in Waifdom’ asserts that reformers hoped, in 1844, that the country might be saved, but that no one was optimistic enough to believe that it would be saved. Sir Walter Besant, credited as being, with Charles Dickens, the most outstanding of the literary friends of the ragged schools, wrote in the year of the Queen’s Jubilee:

“How this country got through without a revolution, how it escaped the dangers of that mob, are questions more difficult to answer than the one which continually occupies historians—how Great Britain, single-handed, fought against the conqueror of the world.” England in 1842 was suffering from a severe economic depression.

Masses of the population were unemployed. There were serious reductions in the wages of the employed. Riots requiring force to quell were a manifestation of popular unrest. The mobs were made desperate by the lack of food and work and, when employed, by the low wages and the conditions under which they labored. Agricultural distress was acute, and rick-burning was common. Many country people, displaced by rural change, had migrated to the towns and cities.

To their ranks were added, toward the end of the decade, large numbers of Irish peasants, escaping from the same great potato famine which was responsible for the wave of Irish immigrants to the United States. In England, their struggle for a place in the economic life aroused the fears and opposition of the already oppressed English laborers. Religious difficulties accentuated these problems. Among the root causes of the social discontent was the working of the “new” Poor Law of 1834.

Under laws dating back to 1572, and principally to the Act of 1601, usually termed the “Elizabethan Poor Law,” each parish had been required to provide, from tax funds, outdoor relief for the able-bodied poor, almshouse care for the infirm, and apprenticeship for needy children. An Act of 1722 required the local authorities to build workhouses where able-bodied paupers were to be employed, and the aged poor, children, and pauper sick were to be cared for.

By the close of the eighteenth century, a regular system of relief in aid of wages had developed, assuring all laborers whose wages fell below a certain level an allowance from the public treasury. Under this system, the numbers of persons receiving relief and relief expenditures had risen steeply, leading to widespread criticism in terms not unlike those used today by critics of our own public assistance programs.

Outdoor relief for the able-bodied poor was terminated, on the recommendation of a Royal Commission appointed in 1832, by the poor-law amendment of 1834. Under it, most of the existing legislation on poor relief was repealed. Indoor relief for the able-bodied poor in workhouses was largely substituted for outdoor relief. This meant that the only recourse for the destitute but able-bodied was care in the workhouse, under conditions inferior to those of the humblest laborer outside.

The new law had disastrous effects on millions of people. Agitation for its repeal was widespread, but no substantial legislative changes were to be achieved for another hundred years. Employment of very young children, for long hours, in many kinds of debilitating occupations, was one of the worst scars of the industrializing nation.

Agitation for child labor reform began early in the century, but by 1831, children were still left entirely unprotected except, relatively speaking, in the cotton mills, where they worked a maximum of twelve hours a day. Certain improvements were made by the Factory Act of 1833, but children, at age nine, could still be employed in various types of mills.

All England, it was said, was horrified by the Parliamentary Commission’s Reports of 1842 and 1843, which showed the deplorable working conditions of children in the mines and manufactories. Corrective legislation was attempted, with Lord Shaftesbury (then Lord Ashley) the articulate champion of such proposals. Major reforms were not achieved until 1847, when legislation marking a great advance was enacted. In connection with these legislative efforts, Lord Ashley had called upon the Government to consider the best means of diffusing the benefits of moral and religious education among the working classes.

Provisions for elementary education in this period were extremely limited. Only a small minority of the population could read or write. Little had been done on a national scale to improve the situation, beyond a small annual grant for education from the Privy Council. This money was divided between the two classes of voluntary schools, British (unsectarian) and National (Church of England). The fees charged by these institutions effectively limited attendance by the poor.

Practically, Sunday Schools and workhouse schools were the only places where instruction, even of the most elementary kind, was available to the destitute. For juvenile delinquents, there was either total neglect or harsh penalties. Mary Carpenter deplored the fact that “the Gaol continues to be the only infirmary provided by the parental care of the State for the care of her erring children’s souls.

To this, all her young criminals, more or less guilty… are indiscriminately consigned;… while our police courts are infested with them, our prison cells swarm with them, our felons’ docks are filled with them—and then they are withdrawn for a short time again from our sight, only to return more hardened.”

The outpouring of social concern and action, which began in the early years of the century and rose to a high point in the later days, was a reflection in part of the economic need for workers with some degree of education. It was, however, the Evangelical movement that played the largest role in effecting social changes.

Sweeping the country in what was “like a great public baptism,” the movement was an outgrowth of the Wesleyan Revival of the eighteenth century. Its chief emphases were on conversion, a confident faith, and a religious life manifested in active work for others. So diversified were the church affiliations of its adherents that it was said to be not a body, but rather a way of thinking.

Under the leadership of Wilberforce, among others, this great religious movement had been mainly responsible for abolishing the slave trade and slavery in the Dominions; it had inspired a great crusade for prison reform led by the notable John Howard. It had promoted the spread of Christian knowledge, including the organization of Sunday schools—literally, schools established to give poor children training in elementary subjects and Christian fundamentals on Sunday, the only day of the week most of them were free from employment or street occupations. Such were the conditions and influences which gave rise to the ragged school movement; such were its inspiration and motivation, and of such faith were its leaders and workers.

Early Years of Ragged Schools

It is difficult to trace a definite demarcation between the Sunday schools and the more comprehensive “ragged schools.” The City Missionaries in London between 1840 and 1845 were responsible for the organization of many Sunday schools serving “ragged” children; the number of such schools in operation grew from five to about forty in these few years.

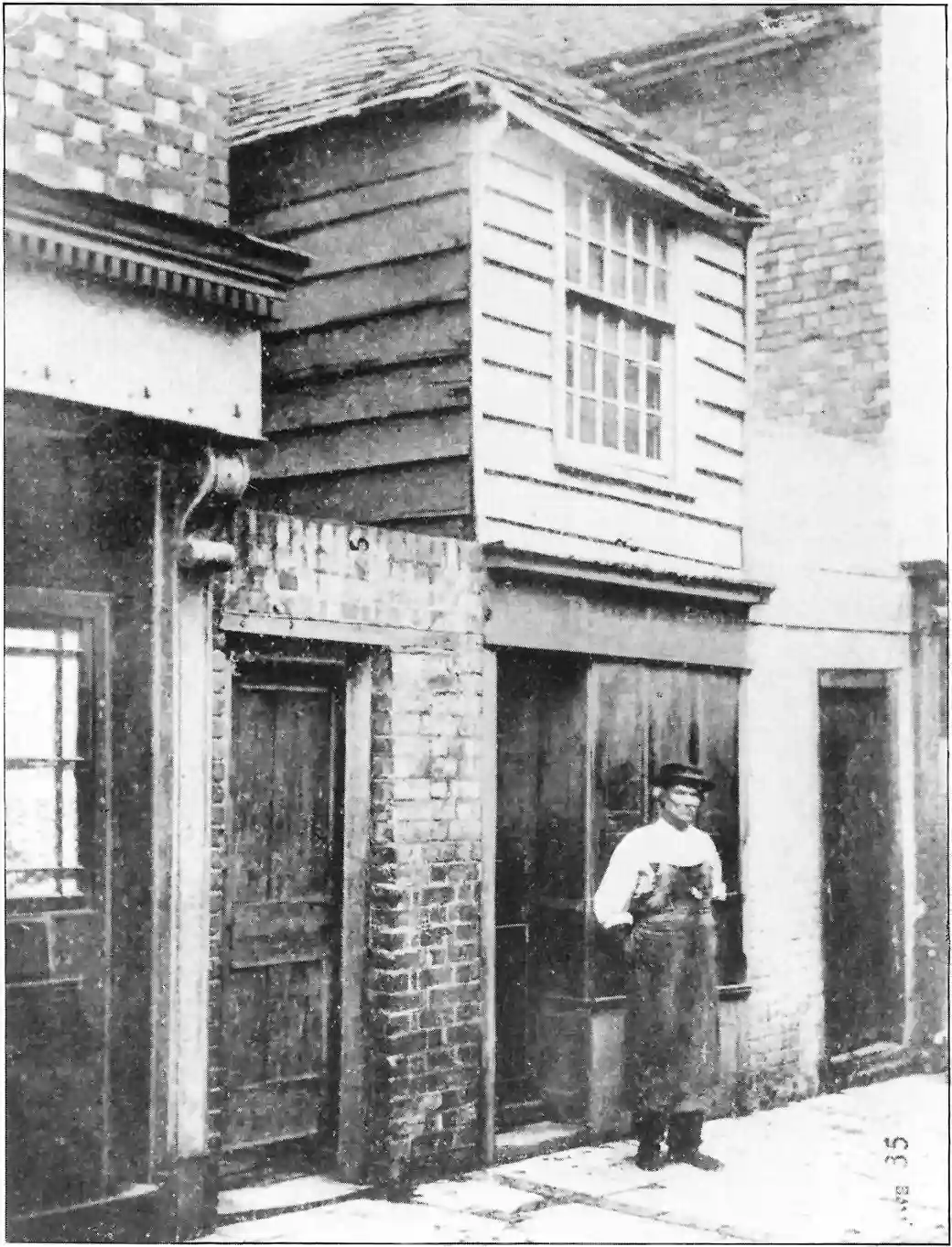

What eventually came to be thought of as the prototype of the ragged schools was started by a cobbler, John Pounds of Portsmouth, himself a cripple and having in his care a crippled nephew. John Pounds undertook to tutor not only his nephew but also a neighbor’s son. From that simple beginning, his efforts grew, and his cobbler’s shop came to serve also as a school where he taught, in subsequent years, a total of over five hundred children, not only giving them “book-learning,” but also teaching them a trade.

In Edinburgh, the Reverend Thomas Guthrie, whose interest had been aroused by news of Pounds’ endeavors, published a series of three “Pleas for Ragged Schools,” which were widely read throughout the British Isles. (In his first “plea,” Dr. Guthrie suggested what is almost an exact counterpart of the “Foster Parents” plan used by some foreign service agencies in the United States today, namely the individual sponsorship of a needy child by a responsible adult.)

After careful planning, Guthrie organized the first ragged industrial schools in Edinburgh. These schools, free of sectarian bias, were conducted seven days a week, and for children otherwise destitute of all these things, they provided food, moral guidance, industrial training, and elementary schooling. Under the stimulus of Guthrie, Shaftesbury, and others, the movement developed rapidly: schools that began as the single endeavors of dedicated individuals gave way to the more comprehensive institutions known as “ragged schools.”

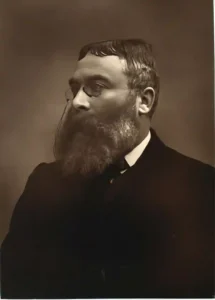

In Lord Shaftesbury, the English waif was to find his greatest and most influential champion. A solitary, self-willed, and deeply melancholy man, Lord Shaftesbury worked for almost half a century for the betterment of the nation’s children, a mission for which his early years seemed to prepare him. Neglected by both his mother and father, it is not surprising that he should remember only one person from his childhood with any degree of affection, a family servant who died soon after the youngster went away to boarding school.

Her kindness had made such an impression on him that he spoke of her always as the best friend he had ever had, and he retained throughout his lifetime the simple, obstinate dogmas of her Evangelical faith and the convictions concerning the sanctions of conduct, the standards of truth, and the sources of revelation which she had inculcated in him before the age of seven. (Of the boarding school, he wrote later that “nothing could have surpassed it for filth, bullying, neglect, and hard treatment of every sort,” adding, “It may have given me an early horror of oppression and cruelty.”)

His three later years at Harrow, which were happy ones, included a very significant event. A plaque on the wall of the Old School records: “Near this spot, Anthony Ashley Cooper, afterwards 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, while yet a boy in Harrow School, saw with shame and indignation the pauper’s funeral, which helped to awaken his lifelong devotion to the Service of the Poor and Oppressed.”

Four years after being graduated from Oxford, he became, in 1826, a member of the House of Commons. His successful effort to amend the lunacy laws was the beginning of a Parliamentary career devoted to the promotion of industrial and social reform. When in 1846 political changes occasioned his temporary withdrawal from Parliament, he spent time visiting London slums and was appalled by the conditions he found there. His efforts from that time on were intensified in behalf of philanthropic efforts and, above all, the rescue and education of the neglected and destitute children of the nation.

In the teaching of ragged school children and the many forms of service and leadership to which it gave rise, people of simple resources and backgrounds joined forces with those of means and learning for the common good of the movement. A body of literature began to appear. One book, ‘Ragged Schools: Their Rise, Progress, and Results’, by John Macgregor, expounded that the hand and eye must be taught to work as well as the head stored with book-learning and called for more trade-oriented classes.

By 1855, there were fifty ragged schools in London with industrial classes, in which about 2,000 children were receiving instruction in a variety of occupations. A decade or so later, a young medical student, John Barnardo, abandoned his preparation for service as a medical missionary in China because he felt a greater call to work with the children of East London’s slums.

After receiving some training for mission work, he became a teacher in a ragged school. Out of his experience there grew an ever-broadening dream of a great Christian mission to juveniles, which must include, he felt certain, homes for destitute children. The dream materialized as the far-flung “Dr. Barnardo’s Homes,” which came to include an emigration scheme. Many of the young people trained in the Barnardo homes emigrated to outposts of the Empire, where they proved themselves pioneers of worth.

Scholars and the Groups from Which They Came

The Ragged School Union had early drawn up a list of the children who should be the special subjects of ragged school labors. It included thirteen categories, but the common factor was the need to educate and civilize a whole population of homeless and vagrant waifs. The police force in London was only a few years old, and the metropolis was fair game for theft and robbery of a simple kind.

The fashions of the day made picking pockets and purses easy. Severe sentences for stealing even small amounts seemed to have little deterrent effect on children bred to thievery in their homes or taught the art by fading-type adult criminals. Their masters—for such they were in fact—profited greatly by the thefts of the agile and clever children. Once under the influences of the ragged schools, these youngsters responded favorably. They showed self-reliance and initiative, qualities naturally required in their lives as thieves but here brought under discipline.

Given a fair field for their energies, they often developed into worthwhile citizens. The population of London included large numbers of families that had left rural districts for lack of any means of livelihood. These families, absorbed into the slums of the metropolis, found only want and destitution. In 1844, the children found in workhouses numbered over fifty thousand. Large numbers of orphans and “ownerless children” roamed at large (very much as did the “Dangerous Classes of New York,” to use the phrase Brace took as the title of his book).

The riversides of London swarmed with them, sleeping and eating where they might. It was these children the Union sought out with earnestness and dedication. This great fervor of reaching out for the neglected child spread rapidly, and cities other than London started their own schools. In Bristol, the able Mary Carpenter noted that all of the children in her school had no shoes or stockings; some had no shirts, some were homeless, and nearly all lived by petty depredations.

Teachers and the Conditions Under Which They Worked

The early teachers, mostly of the working class, occasionally of the middle class, were very frequently those whose lives brought them into situations where they witnessed the tragedy of a slum-child’s life. “Christians all over London,” stated Montague, “had embarked in small, personal, inexpensive ventures, having for their object the moral benefit of as many neglected little ones as they could manage.”

The children crowded into their schoolrooms, which were often on the ground floors of modest dwellings. General exhortations did no good. The children had to be reached by establishing personal relationships of love and care between teacher and pupil. They had to be taught to read. Neighbors and friends, pressed into service for teaching aid, gave their time plus such financial help as they could manage from their small means.

It is difficult for us to imagine how large numbers of children could be kept in order, taught, or influenced in any way when so many were assembled in structures such as soon came to be utilized—a stable, a loft, or any structure that was roomy, cheap, and not sub-divided. Children were reached, guided, and taught in rapidly increasing numbers. Mary Carpenter’s mother stated, “There was no lack of pupils; numbers very often could not be admitted for want of room, or want of teachers, and a policeman, in some cases, was kept at the door to drive away those who wished to force themselves in.”

There were failures, of course, many of them, but that the children in very large numbers responded to and profited from what was made available to them seems to have been well established. The speedy evolution of a simple ragged school to something better designed to meet their pupils’ needs is portrayed in ‘Sixty Years in Waifdom’ with exceptional clarity. Soon classes of a distinctly educational character were held on certain evenings during the week.

But attendance of volunteer teachers was never certain, necessitating the employment of some individuals whose presence could be required at the school under all circumstances. Slowly, the schools became better organized. First a custodian of the key, who also kept the place clean, was required, and then a resident caretaker. To meet the increasing obligations, clergymen were prevailed upon to make appeals from their pulpits. Links were formed with supporting churches, resulting in a measure of stability in financing and a more or less continuous supply of workers.

Churches and chapels started their own schools, not hesitating to utilize teachers from outside their own communion. These efforts were soon augmented by the leaders of the movement, who, in a very few years, with the help of a sympathetic press, made all London, it was said, aware of the possibilities inherent in the work.

In terms of numbers, the growth of the movement was amazing. In 1844 in London, there were estimated to be 20 schools, and, four years later, 82; likewise, the number of teachers increased from 200 to over 1,000, and the scholars from 2,000 to more than 14,000. In less than fifty years, the scholars multiplied to over 50,000 and the voluntary teachers to 5,000. In evaluating the figures on the number of scholars, Mary Carpenter noted the great irregularities in the attendance of many pupils.

If it had been possible to analyze these statistics, she thought it probable that it would be shown that a large number of those enrolled were mere wanderers who remained only a few weeks at the school. To be a successful teacher, Miss Carpenter pointed out, it was not enough to ardently desire to do the work or to bring a persevering and devoted heart to it. It was necessary also to know how to teach, and how to adapt one’s manner and language to the deprived children.

Since so much of the teaching was done by volunteers, their inadequate numbers and irregular attendance was always a matter for deep regret. “Yet,” she said, “on the power of these uncertain voluntary teachers depend the results of the undertaking, whether for good or evil.” In her treatment of this subject, Miss Carpenter gave examples of both well-conducted and hopelessly disordered schools.

As a striking instance of the former, she described a small school near Bristol that had been opened for poor quarrymen and donkey-drivers who were notoriously rough and vulgar in their deportment. “The change after a year’s kind and persevering instruction by a gentleman who devoted to them his evenings after a day’s toil was almost incredible…. ‘Before,’ they said, ‘we did not know that anyone in the world cared for us.’ Great, indeed, is the change that the being ‘cared for’ has wrought on them.”

The Ragged School Union and the Growth of the Movement

One year after its formation in 1844, the Ragged School Union instituted annual public meetings with published reports. The first meeting, not surprisingly, expressed concern over the lack of funds for daily teachers. The 1848 meeting, with an audience of thousands, was evidence of a rising popularity in the cause. A donation from Victoria was a sign of royal recognition, and public support was quick to follow.

The organization of the Union was a loose one, great independence remaining with the individual schools. Its headquarters and personnel were modest. It gave financial aid and counsel to the London schools and encouragement to those wishing to start schools in other cities. An active correspondence was carried on with interested people in other localities, and deputations from the Union sometimes visited such communities to stimulate and assist their efforts.

By 1851, the concept had been developed that a ragged school was an all-the-week-around work. Original objectives were faithfully adhered to. “Stick close to the gutter” was an admonition always being given. Some leaders put special stress on visits to the homes of the scholars. The necessity for technical instruction, which would prepare the students for employment in a variety of occupations, resulted in the formation of industrial classes, forerunners of the later industrial schools and technical institutes.

Night shelters were attached to some schools. Boys’ clubs were organized. An emigration scheme was started whereby the emigrating of trained young people to the colonies was financed. A uniformed brigade of shoe-blacks was organized and operated under well-defined principles. Homes and refuges were established, and later, services for crippled children were inaugurated.

As most of these and other special programs took form, they came to be independent of the Ragged School Union but retained its friendly interest and encouragement and remained closely related to it. Developments continued. Numerous agencies for dealing with health, industrial training, and general family and child welfare matured, and great advances in the provision of resources for general education were made.

The later decades of the century saw the rise of settlement houses, charity organization societies, and the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Important reforms in the treatment of juvenile delinquency were achieved. Reformatories and refuges for children were developed, with the Union aiding such institutions on a capitation basis.

In 1893, Dr. Barnardo could say of the Union, “Now free education lies at the door of every child, but you first pointed the way and carried it out to the slums and back courts.” While increasing support from influential circles had removed the programs of the Union from the position of being a questionable fad of fanatical Evangelicals, there were still many struggles, disappointments, and reverses to follow. They centered, largely, upon the first and central purpose of the movement: education.

The passage of the Education Act in 1870 was a triumph for those who recognized the importance of education for all. However, it necessitated a marked re-direction of the Ragged School Union. The spread of cholera during the sixties had resulted in a drop in the number of scholars and the closing of some schools. The effects of material changes in the metropolis, including developments along the waterfront, the widening of streets, and the opening of new streets, displaced many poor families in districts where ragged schools had flourished.

Thus, the Union had been weakened just prior to a period of struggle and conflict. After the passage of the Education Act, there was a general tendency to assume that all that needed doing among poor children would now be done by the state. Lord Shaftesbury recognized the great advance accomplished by the Act (followed in 1892 by the complete abolition of school fees), but he feared the spread of secularism and had a great distrust of officialdom.

The account of the Union and its growth from 1870 to 1900 is one of difficulties met and temporary reverses overcome. Programs were expanded successfully and new concepts of help and teaching introduced—all with the single idea of the disadvantaged youth being helped to become a useful member of society.

Thus, the Ragged School Union served the children of London in the closing years of the nineteenth century and entered upon the twentieth. With many reservations concerning the policies and methods of the diverse social agencies existing at this later period, Montague insisted on the centrality of the “power of God unto the full salvation of the entire personality of the individual.” To this, he added the admonition, “Begin with the child,” and quoted Lord Shaftesbury in stressing that “expediency and love” should be the rule for all ragged school work.

The Past is Prologue

In 1904, Montague was asking his reader to cast his mind back sixty years to the London of 1844. That was the year when four men decided to draw together in a loose and flexible organization the scattered efforts of those who were striving to reach and to save the forlorn and outcast children of England’s metropolis.

It is hoped that the foregoing pages may help today’s reader to span an interval more than twice as long and to enter into the feelings and the aims of those whose mission was conceived and carried on within the memory of none now living. As he follows the author’s account through the succeeding decades, the reader will be deeply moved by the pathos and the glory of the adventure. The plight of the most lonely, unloved, and outcast children of that time will arouse his compassion.

The deeply held Christian beliefs and convictions of their friends, who with faith and love strove to rescue and nurture them, will command his respect and admiration. The simple beginnings and the proliferation and refinement of their efforts, as they came to comprehend more fully the complexity and the diversity of the needs they were trying to meet, the growing understanding and support they received from the most humble and the most elevated in the land, may give him encouragement as he faces the more complex problems of our own time.

It is fortunate that the author was writing, not as an impartial observer nor a critical analyst of the movement, but as one by birthright and example a loving member of the ragged school family. Only such an author could help us, as well as his readers of two generations ago, to feel and to comprehend the depth of emotion and the strength of purpose which undergirded one offshoot of the great Evangelical movement.

As we do so, we should be thankful for the help it gave in drawing together the diverse elements of nineteenth-century England, incorporating into the common life many who had been most removed from it, and preparing the people and the leaders of Britain for the vastly greater challenges, reverses, and achievements of our own century.

Katharine F. Lenroot

Princeton, New Jersey

January, 1970

This is a verbatim reproduction of the introduction to the book ‘Sixty Years of Waifdom’ by C. J. Montague