A Plea For Ragged Schools; Or Prevention Better Than Cure. By The Rev. Thomas Guthrie.

“Can hope look forward to a manhood raised on such foundations?”

“‘Hope is none for him!’ The pale recluse indignantly exclaimed; ‘And tens of thousands suffer wrongs as deep.’”

“At this day, who shall enumerate the crazy huts and tottering hovels, whence do issue forth a ragged offspring, with thin upright hair, crowned like the image of fantastic Fear; or wearing (shall we say?) in that white growth an ill-adjusted turban, for defense or fierceness, wreathed around their sunburnt brows by savage Nature? Shrivelled are their lips; naked, and colored like the soil, the feet on which they stand, as if thereby they drew some nourishment, as trees do by their roots, from earth, the common mother of us all. Figure and mien, complexion and attire, are leagued to strike dismay; but outstretched hand and whining voice denote them suppliants for the least boon that pity can bestow.”

—Wordsworth.

Table of Contents

A Plea For Ragged Schools

On approaching Edinburgh from the west, after the general features which distance presents—dome, spire, and antique piles of building, the Castle standing in the foreground, while Arthur Seat raises its lion-like back between the city and the sea—the first object which attracts the eyes of a stranger is a structure of exquisite and surpassing beauty. It might be a palace for our Queen; it is a hospital. Nearby, embowered in wood, stands an edifice of less pretensions, but also of great extent; it is another hospital.

Within a bow-shot of that, again, some fine open towers rise from the wood over a fair structure, with its Grecian pillars and graceful portico; it is another hospital. Now in the city, and wheeling round nigh to the base of the Castle rock, he drives on by Lauriston. Not far away, on the outskirts of the town, pleasantly planted in a beautiful park bordered with trees, stands an old-fashioned building; it is another hospital.

On his way along Lauriston, within a stone’s throw of him, his eye catches the back of a large and spacious edifice, which looks beautifully out on the Meadows, the low Braid Hills, and the distant Pentlands; it is another hospital. A few turns of the wheel, and before him, within a fine park—or rather ornamental garden—stands the finest structure of our town, a masterpiece of Inigo Jones, with a princely revenue of £15,000 a year; it is another hospital.

The carriage now jostles over a stone; the stranger turns his head and sees, but some hundred yards away, a large Dutch-like structure stretching out its long lines of windows, with the gilded ship, the sign of commerce, for weather-vane on its summit; that is another hospital. Our friend concludes, and not without some reason, that instead of the “Modern Athens,” Edinburgh might be called the City of Hospitals.

I have no quarrel at present with these institutions: their management is in the hands of wise, excellent, and honorable men; and, in so far as they fail to accomplish the good intended, it is not that they are mismanaged; the management is not bad; but in some of its elements the system itself is vicious. God never made men to be reared in flocks, but in families. Man is not a gregarious animal, other than that he herds together with his race in towns, a congeries of families. Born with domestic affections, whatever interferes with their free and full play is an evil to be shunned, and, in its moral and physical results, to be dreaded.

God framed and fitted man to grow up, not under the hospital, but the domestic roof—whether that roof be the canvas of an Arab tent, the turf of a Highland shieling, or the gilded dome of a palace. And as man was no more made to be reared in a hospital than the human foot to grow in a Chinese shoe, or the human body to be bound in ribs of iron or whalebone—acting in both cases in contravention of God’s law—you are as sure in the first to inflict injury on his moral, as in the second on his physical constitution. They commit a grave mistake who forget that injury as inevitably results from flying in the face of a moral or mental, as of a physical law. So long as rice is rice, you cannot rear it on the bald brow of a hilltop: it loves the hollows and the valleys, with their water-floods; and so long as man is man, more or less of damage will follow the attempt to rear him in circumstances for which his Maker never adapted him.

But apart altogether from this, who and what are the children that under the roof of these crowded hospitals receive shelter, food, clothing, and instruction? It is much deplored by many, and can be denied by none, that in some of these hospitals not a few of the inmates are the children of those who are able, and ought to be willing—and, but for the temptation these institutions present, would be willing—to train up their children as olive-plants around the domestic table, and rear them within the tender, kind, holy, and heaven-blessed circle of a domestic home—a home where they might nurse those precious affections toward parents, brothers, sisters, and smiling babes—which, for man’s good in this life, and the well-being of society, are worth more than all Greek and Roman lore.

I cannot better convey my ideas and feelings on this matter than by saying that when I was a Governor of Heriot’s Hospital—an hospital which enjoys the care and attention both of the Town Council and the city clergy—I was astonished to be applied to by a respectable man on behalf of his son. Let me not be misunderstood. I do not much blame parents and guardians for availing themselves of these hospitals, even when they might do otherwise. A well-furnished table, lodging the most comfortable, a first-rate education, in some instances valuable bursaries, and occasionally, when launched into the world, a sum of money to float the favored pupil on—these present a temptation to tear the child from a mother’s side, and send it away from a father’s care, which it is not easy to resist.

Still, to resume my narrative, I was amazed to receive such an application from such a quarter. The applicant was a sober and excellent man, living in what the world would count respectable circumstances. Knowing this, nevertheless I asked him, “Can you give your boy pottage in the morning?” “Yes,” said he, surprised at such a question. “Potatoes to dinner?” “Certainly.” “Pottage at night?” He looked astonished: he knew, and I knew, and all his neighbors knew, that he was able to do a great deal more. “Then,” I said, “my friend, were I you, it should not be till they had laid me in my coffin that boy of mine should lose the blessings of a father’s fireside and be cast amid the dangers of a public hospital.”

I may perhaps add that I thought him a wise man, for he took my advice. And before leaving these hospitals, I think it right also to add, in justice to the management of Heriot’s Hospital, that some £3,000 a year is applied to the maintenance of schools scattered up and down the city, where the children of decent tradesmen, mechanics, and laborers receive a good gratis education.

Now, to resume, for convenience sake, the company of my stranger friend. Skirting along the ruins of the old city wall, and passing down the Vennel, we descend into the Grassmarket—a large, capacious place; with the exception of some three or four modern houses standing as it did two centuries ago—the most perfect specimen in our city of the olden time. Its old massive fronts, reared as if in picturesque contempt of modern uniformity—some with the flat roofs of the East, and others of the Flemish school, with their sharp and lofty gables topped by the rose, the thistle, and the fleur de lis—still look down on that square as in the days when it was one sea of heads, every eye turned to the great black gallows, which rose high over all, and from which, amid the hushed and awful silence of assembled thousands, came the loud last psalm of a hero of the Covenant, who had come there to play the man.

In a small, well-conditioned town, with the exception of some children basking on the pavement and playing with the dogs that have gone over with them to enjoy the sunny side, between the hours of ten and one, you miss the Scripture picture of “boys and girls playing in the street.” Not so in the Grassmarket. On one side of this square, in two-thirds of the shops (for we have counted them), spirits are sold. The sheep are near the slaughter-house—the victims are in the neighborhood of the altars.

The mouth of almost every close is filled with loungers, worse than Neapolitan lazzaroni—bloated and brutal figures, ragged and wretched old men, bold and fierce-looking women, and many a half-clad mother, shivering in cold winter, her naked feet on the frozen pavement, a skeleton infant in her arms. On a summer day, when in the blessed sunshine and warm air, misery itself will sing: dashing in and out of these closes, careering over the open ground, engaged in their rude games, arrayed in flying drapery, here a leg out and there an arm, are crowds of children: their thin faces tell how ill they are fed; their fearful oaths tell how ill they are reared; and yet the merry laugh, hearty shout, and screams of delight, as some unfortunate urchin, at leap-frog, measures his length upon the ground, also tell that God made childhood to be happy, and that in the buoyancy of youth even misery will forget itself.

We get hold of one of these boys. Poor fellow! it is a bitter day; he has neither shoes nor stockings; his naked feet are red, swollen, cracked, ulcerated with the cold; a thin, thread-worn jacket, with its gaping rents, is all that protects his breast; beneath his shaggy bush of hair he shows a face sharp with want, yet sharp also with intelligence beyond his years. That poor little fellow has learned to be already self-supporting. He has studied the arts—he is a master of imposture, lying, begging, stealing; and, small blame to him, but much to those who have neglected him, he had otherwise pined and perished. So soon as you have satisfied him that you are not connected with the police, you ask him, “Where is your father?” Now, hear his story—and there are hundreds who could tell a similar tale.

“Where is your father?” “He is dead, Sir.” “Where is your mother?” “Dead too.” “Where do you stay?” “Sister and I, and my little brother, live with granny.” “What is she?” “She is a widow woman.” “What does she do?” “Sells sticks, Sir.” “And can she keep you all?” “No.” “Then how do you live?” “Go about and get bits of meat, sell matches, and sometimes get a trifle from the carriers for running an errand.” “Do you go to school?” “No, never was at school; attended sometimes a Sabbath school, but have not been there for a long time.” “Do you go to church?” “Never was in a church.” “Do you know who made you?” “Yes, God made me.” “Do you say your prayers?” “Yes, mother taught me a prayer before she died; and I say it to granny afore I lie down.” “Have you a bed?” “Some straw, Sir.”

Our stranger friend is astonished at this—not we; alas! we have ceased to be astonished at any amount of misery suffered, or suffering, in our overgrown cities. You have, says he, splendid hospitals, where children are fed, clothed, and educated, whose parents, in instances not a few, could do all that for them; you have beautiful schools for the gratis education of the children of respectable tradesmen and mechanics: what provision have you made for these children of crime, misery, and misfortune!

Let us go and see the remedy which this rich, enlightened, Christian city has provided for such a crying evil. We blush, as we tell him there is none. Let us explain ourselves. Such children cannot pay for education, nor avail themselves of a gratis one, even though offered. That little fellow must beg and steal, or he starves; with a number like himself, he goes as regularly to that work of a morning as the merchant to his shop or the tradesman to his place of labor. They are turned out—driven out sometimes—to get their meat, like sheep to the hills, or cattle to the field; and if they don’t bring home a certain supply, a drunken father and a brutal beating await them.

For example, I was returning from a meeting one night, about twelve o’clock: it was a fierce blast of wind and rain. In Princes Street, a piteous voice and a shivering boy pressed me to buy a tract. I asked the child why he was out in such a night and at such an hour. He had not got his money; he dared not go home without it; he would rather sleep in a stair all night. I thought, as we passed a lamp, that I had seen him before. I asked him if he went to church. “Sometimes to Mr. Guthrie’s,” was his reply.

On looking again, I now recognized him as one I had occasionally seen in the Cowgate Chapel. Muffled up to meet the weather, he did not recognize me. I asked him what his father was. “I have no father, Sir; he is dead.” His mother? “She is very poor.” “But why keep you out here?” and then reluctantly the truth came out. I knew her well, and had visited her wretched dwelling. She was a tall, dark, gaunt, gypsy-looking woman, who, notwithstanding a cap of which it could be but premised that it had once been white, and a gown that it had once been black, had still some traces of one who had seen better days; but now she was a drunkard, sin had turned her into a monster; and she would have beaten that poor child within an inch of death, if he had been short of the money, by her waste of which she starved him and fed her own accursed vices.

Now, by this anecdote illustrating to my stranger friend the situation of these unhappy children, I added that, nevertheless, they might get education and secure some measure both of common and Christian knowledge. But mark how, and where. Not as in the days of our blessed Saviour, when the tender mother brought her child for His blessing. The jailor brings them now. Their only passage to school is through the Police Office; their passport is a conviction of crime; and in this Christian and enlightened city, it is only within the dark walls of a prison that they are secure either of school or Bible. When one thinks of their own happy boys at home, bounding free on the green, and breathing the fresh air of heaven—or of the little fellow that climbs a father’s knee, and asks the oft-repeated story of Moses or of Joseph—it is a sad thing to look in through the eyelet of a cell door, on the weary solitude of a child spelling its way through the Bible.

It makes one sick to hear men sing the praises of the fine education of our prisons. How much better and holier were it to tell us of an education that would save the necessity of a prison school! I like well to see the lifeboat, with her brave and devoted crew; but with far more pleasure, from the window of my old country manse, I used to look out at the Bell Rock Tower, standing erect amid the stormy waters, where, in the mists of day the bell was rung, and in the darkness of the night the light was kindled; and thereby the mariners were not saved from the wreck, but saved from being wrecked at all. Instead of first punishing crime, and then, through means of a prison education, trying to prevent its repetition, we appeal to men’s common sense, common interest, humanity, and Christianity, if it were not better to support a plan which would reverse this process and seek to prevent, that there may be no occasion to punish.

But it may be asked, would not this be accomplished by the existence and multiplication of schools, where, in circumstances of necessity, a gratis education may be obtained? We answer, certainly not. Look how the thing works, and is working. You open such a school in some poor locality of the city; among the more decent and well-provided children there is a number of shoeless, shirtless, capless, ragged boys, as wild as desert savages. The great mass of those in the district you have not swept into your school; but grant that through moral influence, or otherwise, you do succeed in bringing out a small percentage—mark what happens.

In a few days this and that one fail to answer at roll-call. Now, an essential element of successful education is regular attendance; for, in truth, the world would get on as ill were the sun to run his course today and take a rest or play the truant tomorrow, and be so irregular in his movements that no one could count upon his appearance, as will the work of education with an attendance at school constantly broken and interrupted. Feeling this, the teacher seeks the abode of the child, climbs some three or four dark stairs, and finds himself in such an apartment as we have often seen, where there is neither board, bed, nor Bible.

Round the cinders, gathered from the street, sit some half-naked children, his poor ragged pupil among the number. “Your child,” says he to the mother, “has been away from school.” I pray the Christian public to listen to her reply. “I could not afford to keep him there,” she answers; “he must do something for his meat.” I venture to say—nay, I confidently affirm—that there are many hundreds of children in these circumstances this day in Edinburgh. I ask the Christian public, what are we to do? One of two things we must do—look at them. First, we may leave the boy alone; by and by he will qualify himself for school.

Begging is next neighbor to thieving: he steals, and is apprehended, cast into prison, and having been marched along the public street, shackled to a policeman, and returning to society with the jail-brand on his brow, any tattered shred of character that hung loose about him before is now lost. As the French say, and all the world knows, “Ce n’est que le premier pas qui coûte.” He descends from step to step, till a halter closes his unhappy career; or he is passed away to a penal settlement, the victim of a poverty for which he was not to blame, and of a neglect on the part of others for which a righteous God will one day call them to judgment.

There is another alternative; and it is that we advocate. Remove the obstruction which stands between that poor child and the schoolmaster and the Bible—roll away the stone that lies between the living and the dead; and since he cannot attend your school unless he starves, give him food; feed him in order to educate him; let it be food of the plainest, cheapest kind; but by that food, open his way to school; by that powerful magnet to a hungry child, draw him to it.

Strolling one day with a friend among the romantic scenery of the Crags and green valleys round Arthur Seat, we came at length to St. Anthony’s Well, and sat down on the great black stone, to have a talk with the ragged boys that were pursuing their vocation there. Their tinnies were ready with a draught of the clear cold water, in hope of a halfpenny. We thought it would be a kindness to them, and certainly not out of place in us, to tell them of the living water that springeth up to life eternal, and of Him who sat on the stone of Jacob’s Well, and who stood in the Temple and cried, “If any man thirst, let him come unto me and drink.”

By way of introduction, we began to question them about schools. As to the boys themselves, one was fatherless—the son of a poor widow; the father of the other was alive, but a man of low habits and character. Both were poorly clothed. The one had never been at school; the other had sometimes attended a Sabbath school. These two little fellows were self-supporting, living by such shifts as they were then engaged in.

Encouraged by the success of Sheriff Watson, who had the honor to lead this enterprise, the idea of a Destitute School was then floating in my brain; and so, with reference to the scheme, and by way of experiment, I said, “Would you go to school if, besides your learning, you were to get breakfast, dinner, and supper there?” It would have done any man’s heart good to have seen the flash of joy that broke from the eyes of one of the boys—the flush of pleasure on his cheek—as, hearing of three sure meals a day, he leapt to his feet and exclaimed, “Aye will I, Sir, and bring the haill land too;” and then, as if afraid I might withdraw what seemed to him so large and magnificent an offer, he again exclaimed, “I’ll come for but my dinner, Sir.”

I have abundant statistics before me to prove that there are many hundreds of children in this town in circumstances as hopeless as those I describe, and who must be fed in order to receive a common moral and religious education; without which, humanly speaking, they are ruined both for this world and the next.

How many there are in more hopeless circumstances still, I never knew, till I had gone to see one of the saddest sights a man could look on. The Night Asylum was not then established; the houseless, the inhabitants of stair-foots—those, like the five boys lately sent to prison, who had no home but an empty cellar in Shakespeare Square—found, at the time when they sought it, or dared to seek it, a shelter in the Police Office. I had often heard of the misery it presented; and, detained at a meeting till past midnight, I went with one of my elders, who was a Commissioner of Police, to visit the scene.

In a room, the walls of which were hung with bunches of skeleton keys, the dark lanterns of the thief, and other instruments of housebreaking, sat the lieutenant of the watch, who, when he saw me at that untimely hour, handed in by an officer and one of the Commissioners, looked surprise itself. Having satisfied him that there was no misdemeanour, we proceeded, under the charge of an intelligent officer, to visit the wards.

The whole tenement. Our purpose is not to describe the strangest, saddest collection of human misery I ever saw, but to observe that there were not a few children, who, having no home on earth, had sought and found a shelter there for the night. “They had not where to lay their head.” Turned adrift in the morning, and subsisting as they best could during the day, this wreck of society, like the wreck of the seashore, came drifting in again at evening tide.

I remember looking down, after visiting a number of wards and cells, from the gallery on an open space, where five or six human beings lay on the pavement buried in slumber; and right opposite the stove, with its ruddy light shining full on his face, lay a poor child who attracted my special attention. He was miserably clad—he seemed about eight years old—he had the sweetest face I ever saw; his bed was the stone pavement—his pillow a brick; and, as he lay calm in sleep, forgetful of all his sorrows, he looked a picture of injured innocence.

His story, which I learned from the officer, was a sad one, but such one as too many could tell. He had neither father nor mother, brother nor friend, in the wide world—his only friends were the Police—his only home their office. How he lived they did not know; but, sent away in the morning, he often returned. The floor of a ward, the stone by the stove, was a better bed than a stair-foot. I could not get that boy out of my head or heart for days and nights together. I have often regretted that some effort was not made to save him. Some six or seven years are now by and gone; and before now, launched on the sea of human passion, and exposed to a thousand temptations, he has too probably become a melancholy wreck.

What else could any man who believes in the depravity of human nature, and knows the dangers of the world, expect him to become? These neglected children, whom we have left in ignorance and starved into crime, must grow up into criminals—the pest, the shame, the burden, the punishment of society; and in the increasing expenses of public charities, workhouses, poor rates, prisons, police officers, and superior officers of justice, what do we see but the judgments of a righteous God, and hear but the echo of these solemn words, “Be sure your sin will find you out!”

From statistics before me, I repeat it again—and it ought to be repeated till a remedy be provided—that there are at least a thousand children in this city (others say some thousands, but I would rather much understate than in the least exaggerate the case), who cannot receive such an education as will bless them and make them a blessing to society unless, along with their education, they are provided with the means of keeping body and soul together.

Let the Christian public observe that while such schools as Lady Effingham’s, Lady Anderson’s, and the Duchess of Gordon’s, and others of the same description, are most creditable to the large-hearted benevolence of these ornaments of the upper and best friends of the lower classes, and are the means of incalculable good to a low class, yet they hardly touch that lowest class for the sake of whose interests I have stepped forth from my own peculiar walk, and now venture, through the press, on this appeal.

The fact may be doubted by some who have never left their drawing-rooms to visit, like angels of mercy, the abodes of misery and crime; but no visitor of the Destitute Sick Society—no humble and hard-working city missionary—no enlightened Christian governor of our prisons—no superintendent of Night Asylum and House of Refuge—none who, like myself, has been called on to explore, amid fever and famine, the depths of human misery in this city, and has come in close, and painful, and heart-sickening contact with its crimes and poverty—I say, none of these will doubt it—at least I have seen none who doubted it.

I implore the public to remember that we have not here the miserable consolation that the infected will die off. They are mixed with society—each an active center of corruption; around them you can draw no Cordon Sanitaire. The leaven is every day leavening more and more of the lump: parents are begetting and breeding up children in their own image; while ignorance, vice, and crime are shooting ahead even of the increase of that population.

I have long felt inclined to add my experience to that of many benevolent and Christian men who have gone before me, regarding the deplorable and dangerous state of the class who form the substratum of society, and also to the miserable provision made even for decent poverty—for those whom the hand of God has smitten—and the manifold temptations they are thereby exposed to; but the pressure of other avocations, the difficulty of getting the public ear in times of excitement, and the lack of any approved remedy for the evil in its first causes must explain my silence in the past.

We had been for some time inclined to hold that such a remedy was only to be found in the schools which we now propose; but till the experience of Aberdeen and Dundee had turned what was but a presumption into a fact, we had not the courage to venture on the proposal. We see no way of securing the amelioration and salvation of these forlorn, outcast, and destitute children but by making their maintenance a bridge and stepping-stone to their education.

It has been tried and proved that without some such instrumentality you cannot get these children to school; at least you cannot get more than the smallest percentage of them; and though you could—though you got the hungry, shivering child into your class—what heart has he for learning, whose pale face and hollow eyes tell you he is starving? What teacher could have the heart to punish a child who has not broken his fast that day? What man of sense—of common sense—would mock with books a boy who is starving for bread? Let Christian men answer our Lord’s question; let everyone who is a parent think of it: “What father, if his child ask for bread, would give him a stone?” And let me ask, what is English grammar, or the Rule of Three, or the A, B, C, to a poor hungry child—what is it but a stone?

I have often met this difficulty in dealing with the grown-up, who possessed what the child does not—sense to understand the importance of the lesson. I have seen it in a way not to be forgotten. It was in the depth of a hard winter day when, visiting in the Cowgate, I entered a room where, save a broken table, there was nought of furniture, to my recollection, but a crazy bedstead, on which, beneath a thin ragged coverlet, lay a very old gray-headed woman.

I began to speak to her about her soul, as to one near eternity; on which, raising herself up and stretching out her bare, withered arm, she cried most piteously, “I am cauld and hungry.” “My poor old friend,” I said, “we will do what we can to relieve these wants; but let me in kindness remind you that there is something worse than either cold or hunger.” “Aye, but, Sir,” was the reply, “if ye were as cauld and as hungry as I am, ye could think o’ nae-thing else.” She read me a lesson that day which I have never forgotten, and which, as the earnest advocate of these poor forlorn children, I ask a humane and Christian public to apply to their case. The public may plant schools thick as trees of the forest; but be assured, unless, besides being trees of knowledge—to borrow a figure from the Isles of the Pacific—they are also bread-fruit trees, few of these children will seek their shadow, far less sit under it with great delight.

Is anyone so ignorant of human nature as to suppose that, offered nothing but learning, these destitute children may be brought to school by the mere power of moral suasion? I would like to know how many of the well-fed, well-clothed, well-disciplined children who crowd our schools would prefer the schoolroom to the playground unless their parents compelled their attendance; but then, it may be answered, try the power of moral suasion on the parents.

Now, we put it to any reasonable man if it be not true that to expect an abandoned drunken ruffian—a miserable, ignorant, poverty-struck widow, whose powers, both of body and mind, grief and want have paralyzed—those who themselves are strangers to the benefits of education—who are living without God and without hope in the world—who are partly dependent for their own stinted subsistence and, in too many instances, the feeding of their vices, on the fruits of their children’s plunder or begging—we ask if to expect that such will compel their hungry children to attend a school is not like seeking for grapes on thorns, or figs on thistles?

We have already indicated how we propose to meet these difficulties: let us be a little more explicit. What we then propose to do, with the intent of meeting, and the confidence of overcoming, difficulties never yet fairly grappled with, and, with God’s blessing, of engrafting on the fair stock of civilization and Christianity these wild vines, so that they shall yield the wine which is pleasant both to God and man, is this: in place of one great school, which would manifestly be attended by many disadvantages, let there be an adequate number of schools set down in the different districts of the city, so that each school shall contain no more than a manageable number of children—not more than a teacher can thoroughly control and break in.

These Arabs of the city are wild as those of the desert, and must be broken in to three habits—those of discipline, learning, and industry, not to speak of cleanliness. To accomplish this, our trust is in the almost omnipotent power of Christian kindness. Hard words and harder blows are thrown away here. With these, alas! they are too familiar at home and have learned to be as indifferent to them as the smith’s dog to the shower of sparks. And without entering into many details, it may be enough to say that in the morning they are to break their fast on a diet of the plainest fare—then march from their meal to their books; in the afternoon they are again to be provided with a dinner of the cheapest kind—then back again to school, from which, after supper, they return, not to the walls of a hospital, but to their own homes.

There, carrying with them many a holy lesson, they may prove themselves Christian missionaries to these dwellings of darkness and sin. This is no vain expectation. Our confidence is in Him who has said, “Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings He ordaineth strength.” And we are all the more confident of His blessing because we are in this the best way fulfilling the duty laid on us in His promise to the forlorn—“When thy father and thy mother forsake thee, then the Lord will take thee up.” A faithful God, He does not do this by way of miracle but by way of means; putting it into the hearts of kind and Christian people to do a father’s and a mother’s part to those who are fatherless and motherless, or to the still more unhappy children who have their parents but would be better without them.

To work up this scheme to its greatest advantage and capability of good, we would strongly recommend the adoption of some such plan as this. In place of benevolent individuals contenting themselves with subscribing to its funds and taking no further interest in the welfare of its objects, let each individual select one child or more, as his means may warrant—say one child. The expenses of its education and maintenance at school are met by him: this is known to the child; and thus, taught to regard him as its benefactor, the better and kindlier feelings of its nature are brought into activity and nurtured into strength.

Within the arms of his gratitude, man can embrace a benevolent individual, but not a benevolent community. What pauper ever left a charity workhouse with a blessing on its Directors? But individual charity has been remembered in the widow’s prayer; and some have walked our streets who could say with the patriarch, “When the eye saw me, then it blessed me.” We attach the utmost importance to the plan we propose. By means of it, the person through whose kindness the child is placed and paid for at school—who comes there occasionally to watch the progress of a plant which he had found flung out on the highway, to be trodden under foot, but which he has transplanted into this nursery of good—becomes an object of kindly regard to the child: the boy fears his displeasure and aims at his approbation; kindness softens his heart; his love and gratitude are kindled; and so we call in the most effectual allies in our effort to save him from ruin.

In this way, moreover, the child has secured a patron and protector—one to take him by the hand when the term of school is closed, and to stand by him in the battle of life. Selecting a boy in whom we have learned to take a kindly interest, we will feel it to be our business to guide him, through our counsel and influence, into some way of well-doing. We will be led to charge ourselves with his welfare. He will not have to complain, “No man careth for my soul.” And so, through the influence of kindly feelings on his part and Christian care on ours, in many a now unhappy child, society might gain a useful member, instead of receiving an Ishmaelite, “whose hand is against every man, and every man’s hand against him.”

On the management of these schools we have only to add that alongside a common and Christian education, we will introduce such work as may suit the age of the children and their condition in life, with the double advantage of lessening, by its profits, the expense of maintenance, and forming in the children habits of industry, which will fit them for an honest and useful life. And thus, through these schools, heaven smiling upon them, we will be able to address these children in the language of God to the patriarch—“I will bless thee, and make thee a blessing.”

We know no solid objection to which our scheme is open. Not that we mean to say it will prove a good without any mixture of evil, or that it cannot by any possibility be abused; but only that, if these are objections, they are objections to which the best and noblest schemes of Christian benevolence are exposed. However, our extreme anxiety for the success of this scheme leads us to address ourselves to some objections that may be conjured up against it.

Now, we beg, in the first place, to observe that this is no scheme to relieve those whose vices have brought them to ruin, or whose indolence keeps them in poverty. We fully accord with this sentiment of the apostle, “He that will not work should not eat.” This is both the judgment of Scripture and of reason. In very mercy to this world, God has linked crime and suffering together; and it were a short-sighted benevolence which, interfering with that law of Providence, would dissolve the connection. Let guilty parents suffer: they have eaten sour grapes—let their teeth be set on edge. But has not God said, “What mean ye, that ye use this proverb concerning the land of Israel, saying, the fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge?

As I live, saith the Lord God; ye shall not have occasion any more to use this proverb in Israel.” And the question which we put to a humane and Christian public is this: Are we, without any efficient effort to save them, to allow these guilty parents to draw down into the same gulf with themselves their innocent and helpless offspring? We do not propose to contaminate our hospitals with such children. Surely it would be one thing to rear the children of the wicked in affluence—to provide them with a finished education—to house them in splendid palaces; and another thing to save them from the pangs of hunger, and from the crimes to which hunger tempts and drives them—to bless them with a simple education, by which they may live decently in this world, and be taught the way to a better.

Let me put a case, and get an answer. In the College Wynd of the Old Greyfriars’ parish, I found a mother, with some three young children by her side, and a pale sickly infant in her arms: she was a drunkard. But there was no bed save some straw there; there was no fire save some slumbering cinders; there was no bread in her house. I learnt this from being constantly interrupted, while speaking to her, by the miserable object in her arms incessantly saying something to its mother. On asking what it said, she burst into tears and told me it was asking for bread, and she had none to give it. They had not broken their fast that day, and it was now past noon.

Fresh from a happy country parish, I was horrified at such a scene and sent out for a loaf of bread. They fell on it like ravenous beasts. Now, the question I ask, and to which I crave an answer, is this: Should I have left these children to die of hunger because their mother was a drunkard? And if not—if what I did was not to be condemned, but rather commended—how ought this scheme to commend itself to the zealous support of Christian men! That food, perhaps, served to spin out for but a little their feeble thread of life: it secured to them no permanent benefit. But we beseech the public to observe that the charity given in the way we plead for does what common charity does not; it secures for every child whose hunger it allays, and whose life it saves, the blessings of a common and a Christian education.

We can fancy some people at first sight alarmed at our scheme as one which will entail additional burdens on the public. Grant that it did; the benefit would more than compensate for the burden. “There is he that scattereth and yet increaseth”—never were the words more applicable—“there is he that withholdeth the hand, and it tendeth to poverty.” But it is not thus that we meet the objection. We meet it fairly in the face: we deny that any additional burden worth mentioning will press on the public. Do you fancy that, by refusing this appeal, and refusing to establish these schools, you, the public, will be saved the expense of maintaining these outcasts? A great and demonstrable mistake.

They live just now; and how do they live? Not by their own honest industry, but at your expense. They beg and steal for themselves, or their parents beg and steal for them. You are not relieved of the expense of their sustenance by refusing this appeal. The Old Man of the Sea sticks to the back of Sinbad; and surely it were better for Sinbad to teach the old man to walk on his own feet. I pray the public to remember that begging and stealing, while in most cases poor trades to those who pursue them, are dear ones to the public. A friend just now tells us of an old beggar, accomplished in his vocation, who used to lament over the degeneracy of the age, saying that “men now-a-days didn’t ken how to beg; that Kelso weel beggit was worth fifteen shillings any day.”

These beggars that you are breeding on the body politic are costly as well as troublesome members of society. Catch yon little fellow, with his pale face and piteous whine, and search, as some of us have done, his wallets, and you will be astonished at the stores of beef and bread concealed beneath his rags. Don’t blame him, however, because he whines on; he must reach his den at night, laden with plunder. You forget that a sound beating may await him if he returns empty-handed; and you also forget that at some expense he has to keep his mother in whisky, as well as his brothers and sisters in food. You have often tried to put down public begging, the dearest and most vicious way of maintaining the poor: till some such plan as ours is adopted, you never can.

Not to speak of the beggars that prowl about our public streets, hundreds of children set out every morning to levy their subsistence for the day, by calls at private houses. They beg when they may—they steal when they can. Such a system is a disgrace to society; its evils are legion; and we can fancy no plan that goes so directly, and with such sure promise of success, to the root of these evils, as that we now advocate. We say with Daniel Defoe, that begging is a shame to any country: if the beggar is an unworthy object of charity, it is a shame that he should be allowed to beg; if a worthy object of charity, it is a shame that he should be compelled to beg.

We can again fancy some apprehensive lest such institutions should prove “a bounty on indolence, improvidence, and dissipation.” We might again answer that the same objection may be urged against all charity, and that unless we are prepared to run some risk, we shall never either obey the command of God to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, or yield to the better feelings of our nature. But let us look more directly at this objection: we are quite ready to meet it. Grant that the scheme were to act so in some cases on the parents; still the good more than counterbalances the evil.

You are using the only means whereby the children can be saved from habits of “indolence, improvidence, and dissipation.” Suppose a man already indolent, improvident, and dissipated, to have four children; without this institution, these grow up in their father’s image. And what happens? We pray the public to observe what happens: the evil is multiplied fourfold. These four, again, become in course of time heads of families—say, each the parent of four children.

And what happens now? The evil by this time is multiplied sixteenfold; and so it rolls on and deepens, like the waters of the prophet’s vision, first reaching the ankle, then rising to the knee, then to the loins, and by and by “it is a river that cannot be passed over—waters to swim in.” How easily and successfully the child is trained to the vices of the man, we have had abundant evidence. It was only the other day that we heard a little child of some eight years of age confess that he had been lately carried home intoxicated; and when he gaily and glibly told this story of early dissipation, it only called forth the merriment of the ragged urchins around.

The sucking babe is drugged with opium; and spirits are administered to allay the cravings of hunger. When examined on the state of her school, a very excellent female teacher in this town acknowledged to us that she had often been obliged from her own small salary to supply the wants of her hungry scholars. She had not the heart to offer the letters to a poor child who had got no breakfast; and some days ago, smelling spirits from a fine little child, she drew from her this miserable confession that her only dinner had been the half of a biscuit and a little whisky.

How early this hapless class are initiated in the use of spirits, came out the other day, to the astonishment of a friend of ours, who, on walking along the streets, observed some boys and girls clustered like bees on and around a barrel. She asked them if it was a sugar barrel; and on learning that it was a spirit one, she said, “You surely don’t like whisky?” “For my part, Mem,” says one, a little girl—thinking, perhaps, thereby to recommend herself—“indeed, Mem, for my part, I prefer the strong ale.”

In sober sadness, we ask, is it not worth running some risk to cure such evils—such a moral gangrene—as facts like these disclose? But grant, again, that the dissipated father, because he sees his poor children fed, educated, and disciplined at your expense, and not his own, is thereby encouraged in habits of vice. What happens? If his children are saved by this institution—and, remember, they cannot be saved without it—at his death society suffers no longer—the evil ceases with himself, and, instead of extending along the line of his posterity and multiplying with their multiplication, is buried in the grave of the drunkard.

As to the idea of any decent, sober, church-going, affectionate father, who at present honestly educates and maintains his family, ceasing to work and taking to drink because he might get the children whom he loves, and for whom he loves to labor, educated and fed in such a school as we suggest, along with the sweepings of the neighborhood—such an idea is surely too absurd to be entertained by any reasonable man. It were waste of time, paper, and public patience to answer an objection so utterly contrary to human nature and all experience.

But I am not content simply to repel the objection and show that such an institution will prove no bounty on indolence, improvidence, and dissipation: I believe the truth lies altogether the other way; and having had more to do than many with the victims of these vices, I may be permitted to express my thorough conviction that the uncared-for and desperate circumstances of the poor often prove strong temptations to the waste that leads to want: they are helpless because they are hopeless; it is often after they get desperate that they get dissipated.

Man thirsts for happiness; and when there is everything in his neglected, and unpitied, and unhelped sorrows to make him miserable, he seeks visions of bliss in the daydreams of intoxication; and from the horrors that follow his excess, he flies again to the arms of the same enchanter. The intoxicating cup brings—what he never has without it—though a passing, still a present feeling of joy and comfort. Of course, I here speak of one who is a stranger to the consolations of religion and the faith of Him who said, “Though the fig tree should not blossom.”

Allow me to say that it is very easy for those who walk through the world rolled in flannels and cased in good broad cloth—who sit down every day to a sumptuous, at least a comfortable dinner—who never have had to sing a hungry child to sleep, nor to pawn their Bible to buy them bread—it is very easy for such to wonder why the poor, who should be so careful, are often so wasteful. “What have they to do with drink?” it is said; “what temptation have they to drink?” I pray them—not that I defend the thing, but detest it—but I pray them, in answer to their question, to hear the testimony of one who knew human nature well. The Laird and Maggie are haggling about a fish bargain.

“‘I’ll gie them,’ says Maggie, ‘and—and—and—half-a-dozen of partans to mak the sauce, for three shillings and a dram.’

“‘Half-a-crown and a dram, Maggie,’ replies the Laird.

“‘Aweel, your honour maun hae’t your ain gait, nae doot; but a dram’s worth siller now—the distilleries is no working.’

“‘And I hope they’ll never work again in my time,’ said Oldbuck.

“‘Aye, aye, it’s easy for your honour, and the like o’ you gentle folks, to say sae, that hae stouth and routh, and fire and fending, and meat and claith, and sit dry and canny by the fireside; but an’ ye wanted fire, and meat, and dry claise, and were deeing o’ cauld, and had a sair heart—which is warst ava’,—wi’ just tippence in your pouch—wadna ye be glad to buy a dram wi’t, to be eilding and claise, and a supper and heart’s ease into the bargain, till the morn’s morning?”

There is a world of melancholy truth in this description. I quote the above as the testimony of a man who had studied human nature; and I now quote what follows, as the inspired words of one whose Proverbs contain the most remarkable record of practical observation and everyday wisdom that the world contains. What says Solomon? “The destruction of the poor is their poverty.” He saw the connection between desperate circumstances and dissipated habits; elsewhere he says, “Let him drink to forget his poverty, and remember his misery no more.”

The truth is that a poor widow, with a babe at her breast and three children at her side, who is mocked with a sixpence a week for each, to meet therewith the expenses of food, fuel, house rent, raiment, and education, is often driven to desperation. She struggles on for a while, and, turning into temporary floats, by the help of the pawnbroker, this article and that, with her children hanging on her, she keeps her head awhile to the stream. At length, having taken her last decent bit of furniture or dress to the pawn, she can contest it no longer—she loses heart—she sees no hope of bettering herself—and, seeking to drown in drink the consciousness of her misery, she is borne down the flood of ruin. If you cannot understand this temptation, I will help you to do so.

On what does that door open, where an officer stands with a sword in one hand and a finger of the other on the trigger of a pistol? Who and what are these desperate and haggard men that press in upon him? A band of pirates who have boarded his ship? And does he stand there to guard its freight of gold? No; he guards its spirit-room. Six days ago, the sea was calm—hope was bright as heaven—the good ship bounded over the billows, and not a man of that band but he had only to say to him, “Go, and he goeth.”

But the storm came, and the sails flew into ribbons, and the masts went by the board, and the seams gaped to the sea, and the pumps were choked, and the vessel lies water-logged now; and the men have strained their eyes for a sail on the wide round of waters, and they have ceased to hope; and the cry has been raised, “To the spirit-room!” and by this time they had drowned their sorrows in intoxication, but that that calm determined man stands there and, having drawn a chalk line across the passage, assures them he will cut down the first that crosses.

Far be it from me to say a word in defense of a crime which is the curse of our people, the shame of our country, and the blot of our Churches. But don’t deceive yourselves; you will never starve men into sobriety. No; but you can starve many into drunkenness. One demon never cast out another; and some seem to know as little of human nature as did the Jews of old, when they blasphemously said of our Divine Redeemer, “He casteth out devils by Beelzebub, the prince of devils.”

I have seen and admired the efforts which a poor man has put forth when a ray of hope broke through the gloom; and, instead of aggravating the dissipation of the poor, I am confident that the hope which such an institution would shed on the dark prospect of many a forlorn family would help to charm and chase the demon away. It would make the widow’s heart sing for joy—it would keep up her sinking head—to see that now her poor dear children had the prospect of being saved; it would have the effect on her that the cry of “A sail!” has had on the mutinous crew, when, in that blessed sight and blessed sound, Hope has boarded their sinking ship, they have returned once more to their right mind, and strained every nerve to keep themselves afloat.

It cannot be denied that at this moment many of our poor are miserably provided for; and, let me ask, how could an addition be so well or wisely made to their wretched pittance as by securing through it an education that, with the blessing of God, would train up the rising generation into honest and useful members of society? The present system is vicious and defective—manifestly defective in this, that if the State or society is bound to maintain the children of the destitute, it is bound to do—what it does not—educate them also; it pretends to do the first—to a large extent it does not even pretend to do the second.

By this scheme, both would be done. If parents and others are inclined to abuse our charity and make it minister to their own vices instead of their children’s maintenance, this scheme goes like a knife to the root of that evil. The children—the innocent sufferers—those who, in the case of dissipated parents, are all the more objects of Christian pity—are, in the institutions we plead for, made sure of food, knowledge, habits of discipline and industry; in short, they are placed beyond the reach of their parents’ rapacity. The principle of our scheme lies here: we feed in order to educate; just because we believe that for the good of the child, for the benefit of society, and for the glory of God, it is better to pay for the education of the boy than pay for the punishment of the man.

We never could clearly see our way to the justice which punishes the child, in cases when it may be truly said, he has less sinned than been sinned against; and we are confident that the sentence which condemns him must be often wrung from reluctant Judges. I cannot transfer to paper the touching description of a trial I heard from the gentleman who is now Procurator Fiscal for the county of Edinburgh. By his office, he is now Prosecutor for the Crown; then he was often Counsel for the prisoner. On the occasion alluded to, he was the advocate of a boy who was charged with theft. The prisoner was a mere child: when he stood up, the crown of his head just reached the top of the bar.

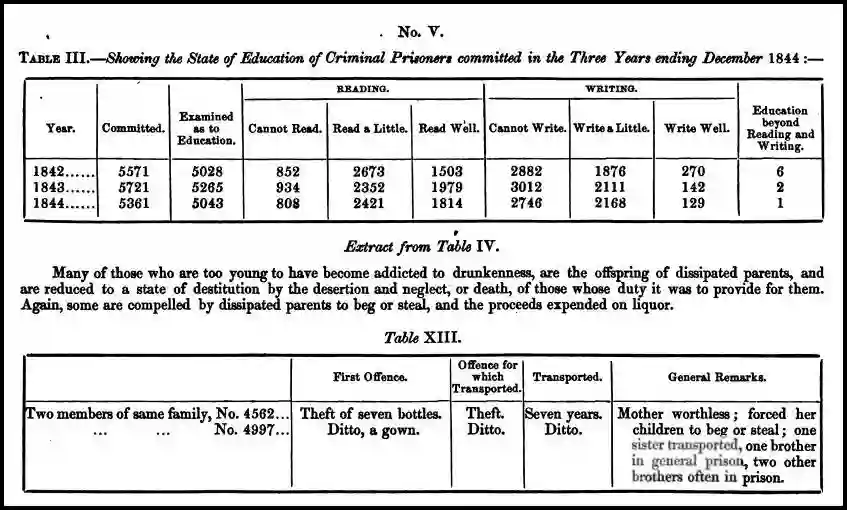

The crime was clearly proved; and now came my friend’s time to shield him from the arm of the law. By the evidence of two or three policemen, he proved that that untaught, unschooled, untrained, uncared-for infant had a brutal parent, by whose cruel usage he was compelled to steal; and then, causing the poor child to be lifted up that he might be seen, and placed upon the bar, in the sight of the wondering, pitying court, he turned round to the Jury-box with this simple but telling appeal: “Gentlemen,” he said, “remember what I have proved; look on that infant, and declare him guilty if you can.” And, I may add, it was but the other day that he told me of a similar case that had come before him when he was called to prosecute a mere child whose father had forced him to steal. The reader will find in the Appendix a painful specimen of such cases, which I have extracted from the Report of Mr. Smith, governor of the prison.

In such cases, justice is perplexed what to do. It is not the heart, but the head also, which is dissatisfied with the punishment; it is not on Mercy, but on Justice, that we call to interpose her shield and protect the victim from the arm of the law. The guilty party is not at the bar; and when the arm of Justice descends on a child whom its country has neglected, abandoned to temptation and left without protection from a parent’s cruelty, in truth she reminds us of the figure that stood some years ago over the courts of law in Londonderry. A heavy storm had swept across the country and, tearing away the scales, had left poor Justice nothing but her sword.

The law in such cases may pronounce its sentence; but humanity, reason, and religion revolt against it. In Scotland, if a man is charged with crime, the Jury, in the case of his acquittal, may return either a verdict of not guilty, or not proven. Where there is strong ground to suspect the party guilty—a moral conviction of his guilt, yet some slight flaw in the legal proof of it—the prisoner is acquitted under a verdict of not proven; and if there are cases where, in truth, the verdict is “guilty, but not proven”—in the case of these unhappy children who are suffering for the crimes of their parents, and neglect of society, with what truth might this verdict be returned, “proven, but not guilty?”

No offence can be committed but there is guilt somewhere. In such cases, however, the guilty party is not the child at the bar. Between the parents, who have trained the child to crime and society, that has made no effective effort to save him, it may not be easy for us to decide where the guilt lies, or in what proportion it is shared between them; but we are thoroughly persuaded that in the day of final judgment there will be found many an unhappy child who has stood at the bar of man, for whose crimes other parties shall have to answer at the bar of God.

We don’t say that society can remedy every wrong; nor do we entertain the Utopian expectation that, by these schools or any other means, crime can be banished from this guilty world; but certainly institutions which will secure to these children a common and Christian education, and habits of discipline and industry, are rich in promise. We know that the returns of autumn fall always short of the promise of summer—that the fruit is never so abundant as the flower; still, however, though we are not so Utopian as to expect that these schools will save all, we have ground, both in reason and Scripture, to expect that they will save many who seem otherwise doomed to ruin.

To take the lowest of all ground—to descend from the high considerations of humanity and the holy interests of morality and religion—to look only at the pecuniary saving—to come down from the profit and the loss of souls to the profit and the loss of money—we claim for this scheme the public support. It may be laid down as an axiom that the prevention of crime is cheaper than its punishment: our schools will more than repay the outlay. Put out of view the return which their work brings in, and which in Aberdeen amounts to a considerable item of the expense, and enter on the one side the expense of these schools, and on the other the saving to the country through the diminution of crime; when the account is closed, we shall have a large balance in our favor.

We pray those who look pale at the probable expense to look at the actual expense of our criminal prosecutions. To confine ourselves to the case of convicts: does the reader know that there are about three hundred convicts annually transported from Scotland? Do the inhabitants of Edinburgh know that their city furnishes about one hundred of these? And that, overlooking the expense of previous convictions, and the money which the subjects of them cost when living by theft and beggary, the expense of their conviction of the offense for which they are transported, and of the transportation itself, is not less than One Hundred Pounds a head?

For convicts belonging to this city we pay Ten Thousand Pounds a year; and for the single item of the trial and transportation of convicts—who are, after all, but a handful of the other criminals—Scotland pays annually about Thirty Thousand Pounds. I have reserved for the Appendix some important matter which bears on this subject, which I have received from others, and to which I would call the candid and careful attention of my readers; but the following table, which Mr. Smith, governor of the prison, has kindly furnished, I think it best to insert here, believing that if sensible men only knew what enormous sums are paid for the punishment of crimes, they would, as a matter of mere economy, hail with pleasure a scheme so likely to prevent it; and that this table will convince many that in doing so little towards the education and salvation of the unhappy outcasts at our doors, we have been for a long time, to use a vulgar but expressive saying, “penny wise and pound foolish.”

Statement of the Expenditure for Criminal Prosecutions, Maintenance of Criminals, etc., for Scotland, for the year 1846.

Expense of prosecutions carried on in name and by authority of the Lord Advocate: £13,775

Sums required by the Sheriffs in Scotland to settle accounts for prosecutions: £49,000

Expenditure under the Prison Boards of the several counties in Scotland, for maintenance, etc., of prisoners: £43,366

Proportion accruing to Scotland for convicts sent to Milbank: £3,932

Proportion accruing to Scotland for convicts sent abroad: £28,830

Proportion accruing to Scotland for convicts at home, Bermuda, Gibraltar, etc.: £7,193

Total: £146,096

In addition to the above, expenses are incurred in the punishment of crime, the amount of which we cannot specify, but which must necessarily be very great, such as—Expense of Court of Justiciary, including Judges’ salaries, travelling expenses on circuits, macers, etc.; salaries of the Lord Advocate, Solicitor-General, and Depute-Advocates; Crown agent’s salary, including assistants, etc. The following should also be included in the charges for the punishment of crime in Scotland:—Expenditure by the several counties, cities, and burghs in Scotland, in supporting their respective police establishments; expenditure by ditto in precognitions and summary prosecutions in criminal cases, not reported by the Sheriff to the Lord Advocate; one year’s interest on capital expended in building prisons, lock-up houses, etc.

Some one has said, “how cheap is charity”—a beautiful saying, which might form the motto of our Industrial Schools. No man, we would think, can read this table of expense without the conviction being borne in on his mind that it is high time to be doing more in the way of preventing, that we may have to do less in the way of punishing crime.

Nothing more strongly recommends the scheme to me than the fact that it reconciles two great and good philanthropists, who seem to be opposed to each other—both lovers of the poor—both earnest for their good—both proposing for the same end what appear different plans—and yet both right. With Dr. Chalmers we have always thought that it was through moral and Christian machinery that our degraded and deep-sunk population were to be raised; for their permanent good we had no faith in any other scheme.

With Dr. Alison, again, we always thought that the maintenance of the poor was miserably inadequate to their wants, and that this stood as a barrier between them and the moral influences by which Dr. Chalmers would ameliorate and permanently improve their character. We agreed with both and confess that we could never very well see how they seemed to disagree with each other. In, as it were, the presence of such men, I speak on this subject with unfeigned humility.

The two schemes may go hand in hand; nay, more—like the twins of Siam, the presence of the one should insure the company of the other; and what, perhaps more than anything else, recommends this scheme, both to our head and heart, is this—it furnishes a common walk for both these distinguished philanthropists. Under the self-same roof, the temporal and the moral wants of our forlorn poor are provided for: both these Doctors meet most harmoniously in our school-room; Dr. Alison comes in with his bread—Dr. Chalmers with his Bible: here is food for the body—there for the soul. Dr. Alison’s bread cannot be abused—Dr. Chalmers’s Bible is heard by willing ears: and so this scheme, meeting the views of both, lays its hands upon them both.

We have been dealing with objectors and objections, if any such there be. We can hardly suppose that any man into whose hands this appeal may fall will toss it aside as an effort made on behalf of those who are not worth saving, either for this world or the next. Read, we pray you, the following passage from that excellent work, the “Christian Treasury.”

“‘Push it aside, and let it float downstream,’ said the captain of a steam-boat on a small western river, as we came upon a huge log lying crosswise in the channel, near to a large town at which we were about to stop. The headway of the boat had already been checked, and with a trifling effort the position of the log was changed, and it moved onward toward the Mississippi. On it went, perhaps to annoy others, as it had annoyed us—to lodge here and there, until it becomes so water-soaked that the heavier end will sink into a sand-bar, and the lighter project upward, thus forming a ‘sawyer’ or a ‘snag.’

It would have taken a little more effort to cast it high upon the land, but no one on board appeared to think of doing that, or anything else, save getting rid of it as easily as possible, for it had not yet become a formidable evil. By and by, if a steam-boat should be going down the river and strike against it, causing a loss of thousands of dollars, if not of life, hundreds will ask the old question, if something cannot be done to remedy such evils, without stopping to inquire whether they cannot be prevented.

“Now, this is the way in which some of us work, who profess to have a better knowledge than that which belongs to the world. We forgot that old proverb, that an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure—that that is the truest wisdom which advises the overcoming of the beginnings of evil. It may cost us less seeming labor to ‘push aside’ the boy who stands at the corner of the street on the Sabbath, with an oath on his lips, than to put forth a little extra effort to get him into a Sabbath-school. But he is not yet a formidable evil to society, and so is left to float down with the current of vice—to continue his growth in sin and reach his manhood steeped in habits of evil, and fixed in a position that may work the ruin of more than one soul.”

Yes, it is very easy to push aside the poor boy in the street with a harsh and unfeeling refusal, saying to your neighbor, “These are the pests of the city.” Call them, if you choose, the rubbish of society; only let us say that there are jewels among that rubbish which would richly repay the expense of searching; and that, bedded in their dark and dismal abodes, precious stones lie there, which only wait to be dug out and polished to shine, first on earth, and hereafter and forever in a Redeemer’s crown.

Dr. Chalmers has eloquently expounded and often practically exemplified the principle that when convinced ourselves, we ought to begin at once, nor delay action till all are ready to move. And in drawing these remarks to a close, we have to mention that, acting on this principle, an Interim Committee of gentlemen have secured premises and taken steps for the speedy opening of a Ragged School in this city. We cast ourselves with perfect faith on God and the support of a humane and Christian public.

We hope to see the matter taken up on a large and general plan, worthy of its merits, and worthy of the metropolis of Scotland. In the meantime, we are content to be mere pioneers in this movement; and for such a noble experiment we trust to be provided with funds amply sufficient for the expenses we incur. The names of the Committee will be found in the Appendix; and we would fain hope that the perusal of this Plea may lead to immediate aid, which may be sent to any of these gentlemen. For such assistance, we can promise a richer return than our thanks—even the blessing of those that are ready to perish.

In closing this appeal, we have only further to add that we are all but confident of public support. We have brought forth revelations of the state of the poor which we believe will be new to many. If any of these read this appeal, their ignorance cannot henceforth excuse their apathy. Such schools, in smaller or greater numbers, are needed in many towns. We hope to see Christians of all denominations and politicians of all parties, throughout the country as well as in Edinburgh, putting forth cordial and combined efforts to establish and extend these Destitute Schools—a name we would recommend for them, in place of Ragged Schools.

Though for the sake of the perishing we may regret the defects and inadequacy of this appeal, we will never regret that it has been made. It were better far in such a cause to fail than to stand idly by and see the castaway perish. If the drowning man sinks before we reach him, it is at least some consolation to reflect that we did our best to save him. Though we bore home but the dead body of her boy, we should earn a mother’s gratitude—we should have a mother’s blessing. We had tried to save him; and from that blessed One who made himself poor that He might make us rich—who was full of compassion, kind and patient to the bad—and who hath set us an example that we should follow his steps—we shall earn at least this approving sentence, “They have done what they could!”

First Edition was in the press, we have found that the Parochial Board of the city had responded to the patriotic call of our efficient magistrate Bailie Mack—an industrial school in connection with the Charity Workhouse being already in process of building, for children having a claim on the poor’s funds of the royalty.

Appendix No. 1.

The reader is requested to answer the following questions:

Is it right to maintain and educate, as in our Hospitals, the children of the better-conditioned classes, and refuse the same and far more needed kindness to poverty and destitution?

Is it right that at our Universities there should be provision made for maintaining and educating the children of the rich, who don’t need it, and none for the poor who do?

Is it right to give twenty millions to set free our West India slaves, and do nothing to save the population here, whom we have abandoned to a state worse than slavery?

Is it right that the poor, in consideration of their poverty, should be exempt from police tax and prison tax—that they should get the means of punishment free, and be hanged for nothing, but not the means of prevention free?

Is it right that the poor and destitute should be provided in crowded spirit shops with so many temptations to crime, and be left with so few inducements to virtue?

Which is best—to build a lighthouse that shall save many from being wrecked, or a lifeboat, which may save some who are so?

Which is best—to pay for the policeman or the schoolmaster—the prison or the school?

Which is best—to prevent crime or to punish it?

Which is best—to educate the boy or punish the man?

Which is best—to feed and educate before crime can be, or after crime has been committed?

Is it not the worst political economy to pay for punishing rather than preventing?—a truth embalmed in the good old saying, “an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure.”

Is it right to do so much to reclaim the heathen abroad, and refuse the only means of reclaiming our heathen children at home?

Is it right that Christians should spend in one year as much money in sumptuous entertainments as would supply the wants and cultivate and Christianize the mind of many a poor forlorn child among us?

Is it right that many who are unworthy should be allowed to beg, and that these worthy objects of charity should be driven to beg?

If each child at this school will not cost more than some £3 or £4 per year, are there not thousands in Edinburgh who could each maintain a child, and never miss the cost?

Would not the thought of the good you did be the purest pleasure?

Since all other means have failed to reach the very lowest class, to lessen or arrest the deepening stream of evil, is not this scheme well worth the trial?

If so, would it be right for us to stand idly by and give no help—lend no hand?

If not, is there any right reason why you should wait till others move?

Appendix No. II.

Extract from a Letter by Mr. Smith, Governor of the Edinburgh Prison, to the Governors of Heriot’s Hospital, dated 28th October 1845.

But, besides the children of parents in narrow or reduced circumstances, who yet enjoy the benefit of these institutions (attending to Heriot’s Schools), there is a great and increasing number of miserable little outcasts of both sexes, who of necessity live partly by begging and partly by stealing, and whom the schools of that noble charity do not reach.

These houseless children of want are growing up in ignorance, misery, and vice. Moral restraint, even in its weakest form, is entirely unknown and unfelt by them; their associations and the influences they are under comprehend all that is brutalizing and worthless; they are neglected by those who should be their natural protectors; and crime, instead of being shunned, becomes with them a necessity and a habit.

This class of children, together with their older associates, makes up that baleful undercurrent which saps the foundations of morality and virtue in society, and from which our prisons are filled. Many young persons who have been decently brought up are ruined by coming into contact with these wretched outcasts; so that the duty of endeavoring to reclaim them possesses a double force, as it points not only to the reformation or welfare of the class in question, but to that of others who, by association with them, might be corrupted.

During the last three years, upwards of 740 children under fourteen years of age were committed to this prison for crime. Of that number, 245 were under ten years of age. Most of these had been the victims of the unkindness and neglect of others. Some of them had no parents and were uncared for by anyone. Others were the children of widowed mothers, receiving a most inadequate out-pension from the parish, and obliged to supplement the miserable pittance at the expense of the moral well-being of their families by going out to work and leaving their children unrestrained in their houses.

They have thus grown up in ignorance and idleness and have been exposed to contamination of all kinds. The parents of many others are dissipated and worthless: far from preventing, they instigate their children to the commission of crime; their example and precept are wholly evil, and their very existence a calamity to their offspring.

I think it will be admitted that a vigorous and effectual effort has never been made in Edinburgh to remedy this fearful state of things; and while I believe that its causes lie too deep for entire removal by anything short of the thorough Christianizing of the masses, yet I respectfully submit that there exist strong grounds for believing that a well-appointed School of Industry would materially mitigate the evil.

The experience of the existing Heriot’s Schools has, I believe, sufficiently demonstrated that there exists a numerous class of wretched children who, by habits peculiar to vagrancy and idleness, place themselves beyond their pale; who do not, and indeed cannot, be expected to appreciate the sound elementary moral and intellectual training given in these institutions. The number of neglected and destitute children wandering about the city, many of them beggars and all in the way of becoming thieves, is probably not less than seven or eight hundred.

These may be apprehended by the police for begging or vagrancy; but as soon as set free, they will return to their former habits. What can they do? They know not, and have never known, anything else; and they must have food. Juvenile begging, with all the evils incident to it, cannot and ought not to be put down unless the food which is sought by means of it is first supplied in another way to those who practice it. To take advantage of this natural want and, by providing for it, confer upon the children at the same time the benefits of industrial training in manual labor and of intellectual, moral, and religious culture, is the object of a School of Industry.

No. 1. Extract from a Report by the County Prison Board of Aberdeen on Juvenile Delinquency

These children are the very outcasts of society and objects of the deepest commiseration to every well-constituted mind. In most cases, from the criminality of their parents but in some from their extreme poverty, these children do not receive from them even the first elements of education; poorly clothed and poorly fed, they are rarely placed at school, and many perhaps are never led to a place of worship; and thus they are never put in the way of doing well and are left, without any fault of their own, to follow every evil inclination from their earliest infancy.

They commence by idling about the streets when they ought to be at home or at school. They soon learn to beg to supply their pressing wants; and from this, the transition is easy to the commission of petty thefts for the same purpose, and so from step to step, till the little boy or girl who some years ago only excited sympathy from the apparently artless tale of distress which procured an alms soon becomes a frequent inmate of our prison cells.

No. 2. Extract from the Report, showing the Effects of Schools of Industry.

It appears, both from the police and prison returns, that since the opening of these schools a marked diminution has taken place in the number of juvenile delinquents, although very many still remain. The boys’ school was opened in October 1841, and from that date up to 1st April 1844 (two and a half years), 281 were admitted; of these, a considerable number have been placed in situations where they can maintain themselves; some are still in attendance; some have been removed by their parents, in consequence of the latter having gotten into employment and thus become able to maintain them; and others have deserted, either because their parents preferred having their earnings as beggars or because they themselves dislike the discipline of the school.

The peculiar feature of the Industrial Schools is the combination of instruction in useful employment with education and food. The children have three substantial meals a day; three hours of lessons, and five hours of work suited to their ages. All the boys (and girls) return to their homes every evening. On Sundays they receive their food as on other days, attend public worship, and they have also religious instruction in school.

No. 3. Extract of a Letter from Mr. Watson, Sheriff-Substitute, Aberdeen, to Mr. Hill, Inspector of Prisons.

We have now no begging children either in town or county. I was rather surprised at the effects produced in the county districts. During the three months preceding 6th July 1843, upwards of a hundred children were found wandering in the county and reported by the rural police. During the corresponding period of 1844, fifty were found. In the corresponding period of 1845, only eight; and from the 8th of June to the 5th of July, none were found.

Appendix No. III