Ragged Schools: The School Day

The Ragged Schools started as a social practice and gained so many practitioners that it became a movement in Britain. The urge for free education and social provision of communities led to so many positive externalities that in the 1870s the Forster government absorbed the Ragged Schools infrastructure built by the communities and bankrolled it as a central function of government. This history is the story of how the provision of a public good came to be understood as more valuable to a country than choosing not to make social provision.

The Teachers

In 1870, when the ragged school movement was at its height, there were 440 paid teachers. To this was added some 3,200 voluntary teachers who taught mainly in the evenings or at the weekends [61: Montague, p. 105. Male teachers were paid £75 a year and women £45 a year]. These voluntary teachers came from diverse backgrounds bringing with them a wealth of different experiences.

They included not only those from the wealthier sections of society but also working class men and women and those who had themselves once been ragged school children. Quintin Hogg worked in the City of London; Thomas Barnardo had a medical training and intended to be a missionary until he saw the poverty of some of those living in London; Henry Adams made and sold baskets at Billingsgate in London and C. J. Montague who chronicled the work of the ragged schools, was one of the original scholars at the King Edward Street Ragged School in Spitalfields, London, when it opened in 1845 [62: Bloomer, p.217]. These were just some of the many ragged school teachers.

There was some criticism of the ragged school teachers, who were viewed as being below workhouse teachers in their social standing but they were also castigated for their lack of teaching skills. It is difficult to say how valid this criticism was, for standards varied from school to school and with each individual. A more serious problem perhaps was the irregular attendance of some of the teachers. In 1868, the average attendance of teachers connected with the Ragged School Union was 2,231 out of 3,247 teachers.

Where teachers did not attend on a regular basis, there could be a lack of continuity in the leaching. Yet despite these problems, the ragged schools could not have operated to the extent that they did without this vast reserve of voluntary labour. Such was the demand for teachers that it could not always be met and there were many occasions, especially as the number of ragged schools grew rapidly, when voluntary teachers were in short supply [63: Clark, pp. 132-3]

Although the ragged school teachers came from different backgrounds and their skills varied, most were guided by the principle that they should command obedience in their pupils by love and firmness rather than by fear or cruelly. In this, the ragged schools wanted to make a stand against the prevailing social mores of the time that held that it was acceptable to inflict often severe punishments on children of all ages.

Thomas Guthrie writing in 1860, spoke for the ragged school movement when he proclaimed that at the Edinburgh Ragged School “Punishments are rare. We work by love and kindness.” [64: Guthrie, Seed, p. 163] Some schools, like St James’s Back Street Ragged School in Bristol, forbade all corporal punishment whilst others held it in reserve, only to be used in extreme cases or where all other methods had failed [65: Webster, pp.268-9].

Even though kindness was stressed, it was still essential that discipline was maintained. Commenting on Thomas Barnardo’s skills as a young teacher at Ernest Street School in Mile End in London, the governing body noted that not only did he possess the necessary ability but that he was also successful in keeping order amongst the children [66: Wagner, p.24]. Where teachers failed to keep their pupils under control the consequences could be serious. In such circumstances the pupils could be destructive of school property and the teachers themselves ran the risk of physical harm.

On an unannounced visit to a newly opened ragged school in London, Lord Shaftesbury was horrified to find “only one or two lamps burning, all the windows broken, two of the teachers outside covered with mud from head to foot, while in the school the master was lying on his back with six boys sitting on him, singing ‘Pop goes the weasel’.” [67: Williamson, p.49].

Quintin Hogg, who started teaching the street-sellers and beggars of London as a young man in his twenties, exemplified the mixture of qualities that made a good teacher. He was described as a man who could be as “tender as a woman to any in pain or trouble, who would sleep night after night among lads he wished to rescue, sharing their food and lives” but at the same time he could also “show an iron firmness where necessary”.

He was noted as being particularly successful with the older, more troublesome boys who not only obeyed but also respected him. His determination to educate the children he found on the streets, led him to establish a number of ragged schools and refuges throughout London [68: Wood, p.41. For a time, Hogg worked as a shoeblack in London and slept on the streets to gain the confidence of the children he wished to help and to try and understand the kind of lives that they led].

Unlike Quintin Hogg who came from a middle class family, Henry Adams, who worked as a ragged school teacher for eighteen years, had experienced the kind of life that many of his pupils knew. From the age of fourteen when his father drowned and the rest of his family were sent to the workhouse, Adams had to fend for himself on the streets of London, finding work and shelter the best he could. In May 1852, when a school was opened in the Whitechapel Road in London, he offered himself as a teacher. Although he knew very little at first, he quickly learnt and became a proficient teacher.

Because of his background, Adams understood the children that he taught and was well aware of the difficulties that they faced. He was described as “universally kind to children even in their very worst and most tiresome moods.” This understanding led him to devote much of his time and energy to his pupils. Apart from teaching almost every evening, he supported the sewing class, which was run by his wife, with his own money, and eventually adopted an orphan boy as his son [69: Champreys, passim].

Praise for teachers such as Quintin Hogg and Henry Adams came not only from those connected with the ragged school movement but also from those they taught. George Acorn, who attended several ragged schools in London, had nothing but admiration for his teachers. What made Acorn respect them was that fact that the teachers did more than what was expected of them and took a genuine interest in the welfare as well as the education of their pupils.

Whilst one teacher invited him home for tea, having stopped at the public baths first so that Acorn could wash, another teacher look the boys to a nearby lecture hall in his dinner hour so that they could hear the talks given there. George Acorn was in no doubt as to the positive effect that such teachers had. Writing of one teacher in particular, he described him as “a common-sense philanthropist, and that fact that nearly all his boys are now respectable members of the community is testimony to his splendid character and wise teaching.” [70: Acorn, pp.24, 67-8]. It was just these sort of qualities, both practical and humanitarian, that meant that some of the teachers were able to have such an effect on the lives of their pupils.

The 3 R’S

The education offered by the ragged schools was mostly of a fairly basic kind, concentrating upon reading, writing and arithmetic. George Acorn was not alone when he found that one ragged school that he attended in London was “very limited in its syllabus.” [71: Acorn, p.67]. Singing and drill were sometimes added depending on the facilities available.

As many of the ragged schools and, particularly those associated with the Ragged School Union, wished to instill the principles of religion and morality in their pupils, there was much stress upon the Bible and its teachings. In some schools the shortage of books meant that Bibles, which were donated to the schools, were the only means of teaching reading and writing [72: Webster, p.255].

As well as prayers and scripture readings, much time was devoted to learning passages from the Bible. At the Coombe Ragged School in Dublin, sixty doctrinal texts formed the basis of the education offered. These were repeated by the pupils each day until they had learnt them by heart. Apart from this, singing was encouraged and was used as a means of light relief. The children sang “bright simple tunes and hymns” such as the one given below:

“I am a little soldier,

I’m only five years old:

I mean to fight for Jesus,

And wear a crown of gold.

I know He makes me happy,

And loves me all the day;

I mean to be a Christian —

The Bible says I may.”

[73: Davies, pp. 13, 53]

The annual report of the York Ragged School for 1850 shows the kind of subjects that were taught at the ragged schools. As can be seen, the leaching was bound within a religious framework and was very regimented:

“7 to 8 o’clock: The children admitted — bathe, wash and change their dress

8: The door closed

8.15: The children drilled and inspected to ensure cleanliness of dress and person — marched orderly into school

8.15 to 45: A hymn sung, a portion of Scripture read by the master, the children questioned on its purport, and instructed in the practical influence it should have on their conduct — a short prayer

9.30: The School lessons commence

8.45 to 9.30: Breakfast, the grace sung before and after

9.30 to 10.30: Writing and arithmetic; The girls retire to their own school room

10.30: In the yard — the school room ventilated

10.45 to 11.15: Spelling and reading

11.15: Scripture lesson

11.45: In the yard — school room ventilated

12: Drill

12 to 1.15: Walking or recreation in the yard

1.15 to 2: Dinner — the children wash”

The afternoon followed a similar pattern, the lessons ending with a hymn, a Scripture reading and a prayer as in the morning. Supper was then provided after which the children changed back into their clothes and were dismissed. Those pupils attending the York Ragged School were fortunate in that each afternoon between 3.45 and 5.30 time was devoted to “industrial occupations with singing” [74: Quoted in Webster, p.254].

Wherever possible, the ragged schools tried to offer their pupils some practical skills. As explained by Thomas Guthrie in 1847, the purpose of these ‘industrial classes’, as they were known, was to train the pupils “in the habits of industry” and by doing so, increase their chances of finding work once they had left the school [75: Thomas Guthrie, Report of a Discussion Regarding Rugged Schools (1847), p.vi]. At the Edinburgh Ragged School, they were able to offer a range of different skills:

“The girls learn to sew, to knit, to wash, to cook; whilst the boys are trained up as tailors, shoemakers, and boxmakers or carpenters. In our country establishment – within a mile of Edinburgh — teaching them to handle the axe, the hoe, and the spade, we fit them for emigration or rural labour.” [76: Guthrie, Seed, p. 163].

Eight years later, John MacGregor was able to report that fifty of the ragged schools in London were offering industrial classes. The boys did tailoring, shoemaking, wood-chopping, horse-hair picking, carpentry, mat making, knitting fisherman’s nets, printing paper bags and ornamental leather work [77: Montague, p. 1 94. The girls did sewing, knitting and embroidery].

The type of work undertaken by girls was much more limited than that of the boys and centred around the domestic skills that would be useful to them as servants and eventually, as wives and mothers. By providing them with the skills learnt both in the classroom and through industrial classes, the ragged schools gave their pupils a better chance of finding suitable work than they would otherwise have had.

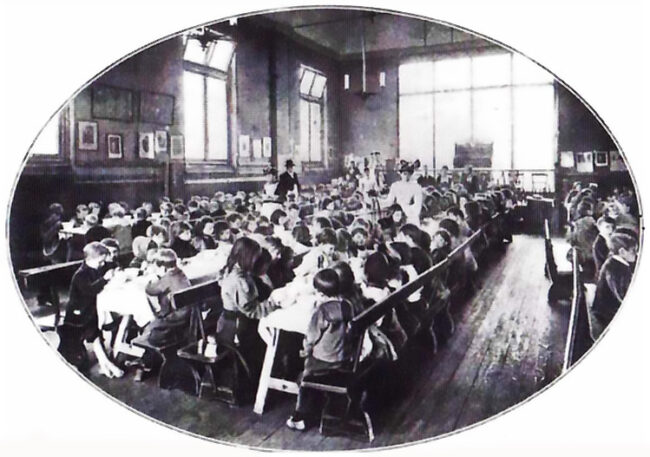

Plain but Substantial Meals

For those connected with the ragged schools, it was all too apparent that not only were their pupils dirty and ragged but many of them came to school hungry. Wherever possible, the ragged schools did what they could to help. At the Coombe Ragged School it was agreed that from the very beginning they would provide food for their pupils. This consisted of “a good breakfast”, apiece of bread al 1pm and for those who had no food waiting for them at home, “a dinner of cocoa, or soup, or rice, or bread and milk” was also provided [78: Davies, pp.9, 12].

The ragged schools realised that by providing food for their pupils they were able to free some children from the necessity of having to work in order to support themselves. As Thomas Guthrie pointed out in 1847, the provision of food was not only a common-sense measure but was also a “powerful magnet” in attracting more pupils [79: Guthrie, Plea, p. 13]. It is not surprising to find, therefore, that attendances tended to rise during the winter months when the shelter, warmth and food offered by the ragged schools were more attractive to their pupils.

At the Edinburgh Ragged School the children were given “three plain but substantial meals a day.” [80: Guthrie, Seed, p. 163]. Not all ragged schools could afford to provide meals on this scale. The Barnsley Ragged School gave its pupils a mid-day meal of bread and soup, which it calculated cost £56 19s 11d per annum [81: Webster, p.240]. One of the schools in London that George Acorn attended was able to arrange dinners for its pupils only twice a week. Fortunately for Acorn, he could, nevertheless, by getting up early in the morning, obtain a free breakfast at a local chapel every day [82: Acorn, p.28].

During times of hardship, special efforts were made by the ragged schools to help those in need. In January 1861, during an exceptionally harsh winter, the George Yard Ragged School in Whitechapel in London provided food for its 400 scholars. They were given “a meal of rice on one day, a meal of bread on another, and a meal of soup, if they can, on the third day.” [83: Hollingshead, p.43].

Sixteen years later, Thomas Barnardo described how, during a “recent trade depression” a free meal was provided once a week for “about five hundred poor children” attending the ragged schools that he had established in the East End of London [84: Thomas Barnardo. Brief Account of the Institutions Known as ‘Dr Barnardo’s Homes’ (1879), p.12].

Barnardo also organised an Annual Waifs’ Dinner at the Edinburgh Castle near Stepney Church and gave food to other groups, providing free meals for factory girls, the unemployed and the aged poor [85: Wagner, p.310]. Some ragged schools distributed food during home visits or like Barnardo, held regular events at which food was provided.

Several organisations offered their help in providing food. In 1878, the Reverend Charles Bullock appealed to the readers of his magazine Home Words to send money to pay for a Christmas meal for the ragged school children. The meal was a success and the event became a regular one in the ragged school calendar with thousands of dinners given each year. By 1896, half a million children had enjoyed a ‘Robin Dinner.’ Such was the poverty of some children attending these dinners that one boy on receiving his meal of roast beef, asked “’Is it Robin we’re eating please, sir?”’ [86: Williamson, p.92].

The Destitute Children’s Dinner Society, founded by the Baroness Rothschild, was another organisation that gave free dinners to the most needy pupils. The Baroness also paid for food to be provided at the New Tothill Street Ragged School in Westminster [87: Clark, p.237. The ragged school teachers, despite their often humble means, were amongst those who provided or paid for food for their pupils]. Numerous other individuals, many of them anonymous, likewise donated money so that the pupils could be fed.

The provision of food not only enhanced life for the ragged school children but for some it was a lifeline. One former pupil recalled how the “meals at the London Ragged School which he and his brother had attended had saved them from starvation.” [88: Williamson, p. 119]. This must have been the experience of other pupils.

Holiday Homes and Tea Parties

As well as providing food on a daily or weekly basis, some ragged schools also arranged special treats for their pupils. At the Barnsley Ragged School the children took part in the Whitsun parades every year, walking the streets with flags until they came to the church, where they attended a short service. Afterwards they went to nearby fields to play and have a picnic [89: Webster, p.47].

Similarly, al the Coombe Ragged School in Dublin, the pupils were treated to a day in the park once a year [90: Davies, p.3 3. The children at the Coombe Ragged School were also treated to “school-feasts” at which tea and cake were provided (p.46)]. Such outings were similar to the Sunday School treats which were organised once a year by individual churches and chapels throughout the country as a reward for those children who had regularly attended during the year.

The ragged schools were helped in the task of providing their pupils with outings and holidays by a number of organisations. In 1892, C. Arthur Pearson set up his ‘Fresh Air Fund’ which was maintained by the readers of his magazine, Pearson’s Weekly. The Fund enabled a large number of children to be sent to the country or to a park for the day by paying for their fares and for two meals during the day. During the first summer of its existence, the Fund gave 20,600 children a day’s holiday in the country. By 1906, some 200,000 children, over half of whom were from London, had benefited from the Fund [91: Hollingshead, p.75; John Stuart, Mr John Kirk (1907), pp.76-8].

The Ragged School Union, amongst others, set up a ‘Holiday Homes’ scheme which gave children a longer holiday in the country. In 1885, the first holiday home for ragged school children opened in Thursley Common, Surrey, which could accommodate twenty children. This was followed by a home in East Grinstead and then in 1887, by a home in Brenchley, Kent. Homes in Bognor, Addiscombe, Margate and Bournemouth followed. By 1906, 6,862 children had been sent on holiday [92: Williamson, p.88].

The length of stay could be anything from a week to a period of months depending on whether a child was just there for a holiday or in need of convalescence. Some of the homes, like the one in Southend which opened in 1893 and could accommodate thirty-six children, specifically cared for crippled children [93: Hollingshead, pp.75, 78].

The chance of a longer holiday in the country was the ultimate treat for many ragged school children. As George Acorn recounted, the experience away from home was not only an extremely enjoyable one but it also made him aware, for the first time, of the world beyond London:

“A kindly association, connected with the school, sent me with other boys to Reading for three glorious weeks, changing my outlook upon Nature and especially London. I had always looked upon open spaces as necessary stretches of green relief for the over-breathed air; but now I saw that the town was a blot upon the fair surface of a green world. When I returned the air of our street was choking to me — I was sorry to have returned. ” [94: Acorn, p. 10]. Whether it was through a holiday or a day in the country, this was another way in which the ragged schools tried to improve the lives of their pupils.

The above research was produced by Claire Seymour first produced in the book ‘Ragged Schools, Ragged Children’ for the Ragged School Museum which on the back page had the following:

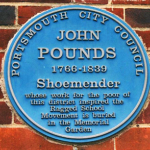

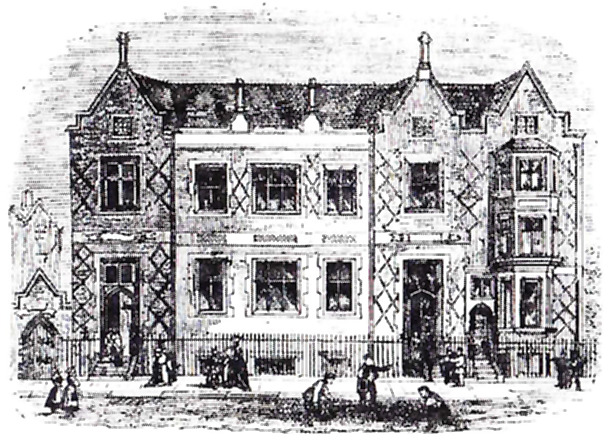

Started in the late eighteenth century the ragged schools aimed to provide an education for the poorest and most destitute children in the country. Such was the need for the ragged schools that, in 1844, the Ragged School Union was formed to encourage the establishment of new schools. As a result, numerous schools throughout the country were founded.

These schools gave thousands of children not only a basic education but much more besides, from food and shelter, to arranging clubs, treats and outings for them. Claire Seymour, who researches social history and is a member of the Ragged School Museum Trust, recounts the history of the ragged schools and tells the story of the children who attended them.

She describes the kind of lives that the children led, their often unruly behaviour and shows how the ragged schools helped them and their families. Also examined are some of the many individuals, such as Dr Thomas Barnardo, whose determination and dedication enabled the ragged schools to succeed.