Mad Studies: The Identitarian Problem

This piece of work although situated in the context of Mad Studies as an academic discipline, is part of work which extends beyond the boundaries of Mad Studies in all directions. These notes are partly a way of talking through various fragments and ideas in order to organise and coordinate a larger study which intersects class, community, gender culture and identity; it is work which is coordinated in a study I am calling ‘Sub-legal Violence’ as a working title.

It is the first publishing of an attempt at formulating what I see as a sociological problem that unfurls anywhere groups of human beings form; it represents part of a larger more comprehensive work which is in development. As the reader might recognise, the Ragged University website has come to operate as an open work book rather than always pieces in their final form – sometimes I have to write things down to change my mind or figure out what I think.

The first section is not peer reviewed and is assembled from notes which have come together in an attempt to articulate a pragmatic pessimism I have been studying in people and populations that relates to common garden bias and prejudice; as well as this, the notes are part of a project which has the focus on identifying mechanisms of endemic disagreement as problems. The second section is a piece of work which submitted as part of a masters degree.

As a social problem, my working title of ‘The Identitarian Problem’ has been the handle for a cluster phenomenon which I have noticed in respect to group dynamics which disrupt coalescence through the external attribution of identity whilst constraining the right to reply. This broad area has been of increasing interest to me as a thinker in order to ground accounts of inclusion/exclusion in the complex social and psychological realities of society as I have experienced it and as it occurs in the world.

At its heart is an exploration of how and why humans perceive difference in situations where more unites people than divides them. Over a life span I have witnessed the seeming arbitrariness of group identities often with puzzlement. It was not until later adulthood that I really started to analyse my experience of going to a faith based school when my cultural background was not of that tradition. Similarly I was baffled as I struggled to understand the behaviours of the city I grew up in and how sport, music, gender, clothes and the geographic location of the house I lived in were used as signs and signifiers shaping who would speak with me, how they would speak, what opportunities were available and a whole host of other realities.

In my later adulthood I came to organised learning (i.e. investing my efforts in systematically attaining understandings of the world) a long time after a rather traumatic experience of formal education. Through friendships and encounters with kindly, interested people, I had been introduced to knowledge as something akin to the pleasure which one would have when experiencing music or art; it was an enrichment that made an inhospitable world viable as a living space by producing islands and oases which provided a habitat – a vital reality to counter the levels of alienation that I experienced.

I became interested in the psychology at play defining which groups you were perceived to be in and how individuals rationalised extending manners to one whilst withholding them from others. I made observations on when within a group, the habits of social order within that group would instrumentalise the individuals in the group sometimes in order to polarize against others and maintain a status configuration – if I was friends with person X then it was incompatible to also be friends with person Y. Understanding behavioural dynamics seemed such an important part of the theatre of Edinburgh, a city which has often been described as ‘a city of castes’.

Table of Contents

An Edinburgh Vignette

For me, someone who was born and lived in Edinburgh, David McCrone, Professor of Sociology describes it well in his 2022 book ‘Who Runs Edinburgh ?’. This offers context to the study I have eventually found myself fully cultivating. I see it as a little Britain that gave me a natural experiment to examine the sociological, behavioural and psychological minutia which composed a culture of small differences; a culture I was never at home in or performing to, a culture which intoxicates people to fall into place with heady fairytales which all come together in an ambiguous illusion looping round on itself – a bipedal ouroboros made pretty like an Escher hand.

The following excerpts are taken from McCrone’s book:

“Edinburgh, or for that matter any city is, above all, a place in which many processes, conflicts and ‘games’ are played out. It is typified as a ‘city of castes’, a description attributed to the nineteenth century journalist, John Heiton, who started his book strikingly: ‘Look you, sir. Your city is a very fine city, but it swarms with castes’. The American was right: Our beautiful Modern Athens is in a swarm of castes, worse than ever was old Egypt or is modern Hindostan,’ (1859:1). A city of casts.” (page 12-13)

“We are frequently asked: what school we went to, and when we might reply (apocryphally) ‘Auchtermuchty High’, the native’s eyes glazed over. Irrelevant answer. What they usually wanted to know was which Edinburgh caste we belonged to; which of the private schools we had attended. If we hadn’t, and worse still, came from outwith the city, it was of little concern to them…the formal political process may be masking an altogether complex and implicit system of power. In other words, there may be a hidden game lying behind the formal political one, a shifting sand of political-economic fortunes. We cannot avoid giving an account of money and economy, how material interets are translated into political ones, indeed, whether this is the case at all. If Edinburgh is ‘a city of castes’, how do these operate today, and particularly affect the spatial distribution of power ? Where do rich and poor people live, and does it matter anyway ?” (page 16-17)

“Edinburgh Castes. It had tended to be ever thus. John Heiton’s Castes of Edinburgh, fifty years previously had made that plain: ‘The Merchants – not great with us – stand between the Professionals and the Shopkeepers; these are getting p; the Big Panes despise the Little Panes. The latter expel the Tradesmen, who erect a nez trousse against the labourers. And these lord it over the Irish Fish-dealers, who will cut an Applewoman of a Sunday.’ (Heiton 1861: 6-7).

Robbie Gray’s study of the labour aristocracy in Victorian Edinburgh showed how status differences – caste distinctions – ran all the way down Edinburgh’s class system, but that ‘the city’s notorious snobbery seems to have derived from social and political rivalries encouraged by this heterogeneity of the wealthier classes’ (Gray 1976: 20). It is not difficult to characterise Edinburgh as a city of class distinctions – ‘snobbery’ – but these social distinctions were not bi-modal, but subtle and multi-varied. Gray (1976: 12) argued that the working class in the city was formed in the context of no unified industrial bourgeois elite:

‘The most prominent middle class groups were not directly involved in relations of production with the manual working class, but were engaged in the professions, wholesale and retail distribution, commerce and finance. The industrial structure was itself heterogeneous, with a considerable amount of smaller-scale labour-intensive industry and a consequent diffusion of ownership’. Edinburgh’s bourgeoisie and proletariat, then, did not stare fixedly across a uniform class divide; indeed, they had little opportunity and reason to do so, because the city’s economies (plural) were diverse and variegated.

‘The industrial working-class in 19th century Edinburgh was thus marked by considerable occupational diversity. A range of old established crafts catered for the large middle-class consumer market, while newer, more capital-intensive enterprise were geared to national and world markets. One feature common to many local industries was their high proportion of skilled labour’. (Gray 1976: 26)

In the final quarter of the nineteenth century, the stratum of ‘superior artisans’ espoused values of ‘respectability’, ‘independence’, and ‘thrift’. This ‘upper stratum created relatively autonomous class institutions and had a distinctive cultural life, articulating a sense of class identity’ (Gray 1976: 184). The labour aristocracy also provided leadership of any working-class movement.

‘The result was transmutation of socialism into labourism, programme of gradualist reforms; a negotiated response to capitalist society; strong sense of class pride and an ethic of class solidarity. This class identity was transmitted in the later nineteenth century to a wider class movement and culture – it is not the least of the legacies of the Victorian labour aristocracy’. (Gray 1976: 190) (pages 52-53)

‘In Edinburgh, you don’t flaunt it. This is the world of clubs, associations which you do not join without an invitation, and without knowing who else is a member. If you have to ask to join, then you’re not their sort of person. Fuelling this world, the story goes, is a complex hierarchy of schools, many, but not all, in the private sector. If Edinburgh is a city of castes, then the question what school did you go to? becomes the key to open doors …

…There is, however, a complex relationship between rhetoric and reality. One might believe that Edinburgh is a hierarchical and closed society – it has myth-status – but we cannot take that for granted, at least in the times we live in. Past and present are in a curious relationship: we cannot rule out that once upon a time the city’s caste-like culture was more important than it is now, while accrediting the myth of caste with considerable power to define the situation as all too credible. But myths have a habit of living on and dragging out in their after-life.’ (pages 112-114)

McCrone’s sociological account all speaks to my experience of the town I grew up in, but the sociological account has extended interest for me as it has fed into my exploring and sketching out what I am calling ‘The Identitarian Problem‘. I don’t think that the ingroup-outgroup dynamic is particular to Edinburgh but suspect that it is more a generalised phenomena which extends throughout Britain partly because of its anthropological domination by privilege and colonialism.

Was Britain the first place to be colonised in the sense of the ‘British Empire’ ? Most significantly from the sixteenth century in Britain the people were set into rank and file order by the peoples who had dominated the culture and developed a god-complex by practicing ‘husbandry’ on all around them.

Overzealous deference culture I see as an indicator of social order which has emerged through an expression of a sort of Sado-Masochistic dynamic that I suspect is a trauma bonding and fetishisation of ‘adaptive preference formation’ – a term defined by MacKenzie as “persons who are subject to social domination, oppression, or deprivation adapt their preferences (or goals) to their circumstances….In social situations characterized by oppression or deprivation, the problem then is not just that restricted opportunities constrain self-determination but also that the internalization of these constraints can shape individuals’ sense of who they are and what they can be and do.” (Mackenzie, 2014).

The deference found in British culture is amusingly summarised by a joke I heard in French which translates to “How do you create a queue in Britain ? Hammer a fence post in the ground”

Excerpt

Mackenzie, C., (2014), ‘Three Dimensions of Autonomy: A Relational Analysis’, In Veltman, A., & Piper, M., (Eds.) ‘Autonomy, Oppression, And Gender’, Oxford University Press. P 30

The snobbery (I include so called ‘reverse snobbery’ in this term) and ingroup dynamics which I have known in Britain has stimulated a keen interest in studying the psychology at play in individuals. There is no absolute generalisation to be made as people are different at different times, and people are different from each other. Having said that, there are undoubtedly cultures of prejudice which mark out and denominate identities without extending a right to response, and those identities shape social associations in terms of homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001) – the way which people of like characteristics often form social groupings.

Abstract

Miller McPherson, Lynn Smith-Lovin and James M. Cook, (2001), ‘Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks’, Annual Review of Sociology Vol. 27, pp. 415-444

An other side to homophily is exclusion, if not active exclusion then the tacit processes of infrahumanisation have been shown to be generally active in how people are perceived and received. Infrahumanization was coined as an extension of the phenomenon of in-group favouritism in which out-group members are viewed as less human than are in-group members.

It describes a form of dehumanisation psychology in which those who are not in the ingroup are perceived as less human (extending the same considerations to others as someone applies to themselves and others they hold close) without there being an explicit polarisation or denigration of those in the outgroup; in simple terms, we may come to perceive people who are proximal to us as more human simply because we are witness to their causal nature more.

This raises questions about the structure of experience which are articulated in ‘The Lesser Minds Problem’ in the field of dehumanisation psychology by Epley and Waytz (2010). The way our encounters with the world and ourselves is structured through our senses may shed light on latent inclinations to perceive our selves and those closest to us as more human. Extending the work on The Lesser Minds Problem, Waytz, Schroeder and Epley (2014) give detail to three essential phenomena that may account for privileging processes in psychology:

- In our existential experience of being, our own thoughts are by incident more vivid and evident to our own apprehension than the thoughts of others

- Our actions as causal have more prominent impact, where the impact of others is experienced secondarily; and

- Our propensity to value our own analyses of the world over others can appear more readily as a self evident truth by way of a thought being operationalised (giving rise to simplistic notions like ‘I have invested of effort in developing a perception so it is more likely to be a better representation of reality’).

Excerpt

“Empathizing with another’ s pain, for instance, generates affective reactions consistent with experiencing pain but not the intense sensory stimulation of actually experiencing pain (Singer et al., 2004). This suggests that the other minds problem might pose something of a problem after all: If introspection vividly illuminates the workings of one’s own mind, it may in many ways seem “brighter” than the minds of others that are viewed less directly through the mechanisms of simulation and theory – driven inference. If people cannot see others’ mental states as easily as they can perceive their own, then they may indeed believe that others have less mind than they have themselves.

Numerous findings converge on this ‘lesser minds’ problem. The most direct comes from studies showing that people believe they possess more mentally complex traits (e.g., ‘analytic,’ ‘imaginative,’ and ‘sympathetic’ ) than others do (Haslam & Bain, 2007; Haslam, Bain, Douge, Lee, & Bastian, 2005), possess more complicated moral sentiments than others do (Epley & Dunning, 2000; Heath, 1999; Kahn, 1958; Miller, 1999), and are therefore more likely to be influenced by these secondary emotional states and moral sentiments than others are (Epley & Dunning, 2000; Hsee & Weber, 1997; Koehler & Poon, 2006; McFarland & Miller, 1990; Miller & McFarland, 1987, 1991; Sabini, Cosmas, Siepmann, & Stein, 1999; Van Boven, 2000).

People also report that they are better able to reason objectively about the external world and are therefore less biased in their judgment than the more simplistic reasoning of others (Pronin, Gilovich, & Ross, 2004), are better able to resist persuasive appeals and mass media attempts to influence their judgment (Davison, 1983; Perloff, 1993; see also Pronin, Berger, & Molouki, 2007), and are more psychologically responsive to the demands of a situation than are others who are seen as responding more mindlessly on the basis of stable and enduring traits (Kammer, 1982; Nisbett, Caputo, Legant, & Marecek, 1973).

People even report that they are more capable mind readers than others, having more insight into other people’s ‘true selves’ than others have into their own ‘true selves’ (Pronin, Kruger, Savitsky, & Ross, 2001). Beyond these self – reported capacities, evidence that others seem to have ‘lesser minds’ emerges from people’s explanations of behavior. People tend to explain their own behavior by appealing to more complicated mental states of beliefs and knowledge — more complicated and late – developing concepts in one’s theory of mind — whereas they explain others ’ action by appealing to the more simplistic mental concepts of wants and desires (Malle et al., 2007). People also recognize more complex relations between their own mental states and behavior than they appear to do when explaining others ’behavior.'”

Epley, N., & Waytz, A. (2010). Mind perception. In S.T. Fiske, D.T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (5th ed., pp. 498–541). New York: Wiley

Excerpt

Waytz, A. Schroeder, J. Epley, N. (2014) The Lesser Minds Problem, In Bain, P. G. (2014). Humanness and dehumanization. New York: Psychology Press.

The understanding that socially diminishing processes are not rarefied instances of extreme circumstances (such as the active devaluation of the cultural groups in situations of war) but exist in the day-to-day environment shaping of encounters with others is important. How social connections form and groups coalesce depends significantly on how our psychology is primed with patterns of characteristics (heuristics) and how we compare people we meet with the images we hold in our minds.

In this research I am interested in understanding how people use these heuristics in order to make judgements, and how these patterned formula suggest themselves as stereotypes; an idea in psychology which comes on loan from ‘a metal printing plate cast from a matrix molded from a raised printing surface, such as type’. The loan-idea suggests in it the idea of fixing an impression which gives a good representation of a standard form, for example, the clarification of the visual essence of a letter and that essence represents all instances of the given letter. I am particularly interested to examine where this pattern recognition function breaks down in practice.

There are a number of perceptual systems we use to parse the world in our day to day activities. Psychologically we model elements of our experience in order to create a cognitive lexicon of the infinite variation we encounter in the complex and changing universe. This cognitive lexicon becomes codified into templates or heuristics so that we may quickly assimilate our current experience and make appropriate behavioural responses to our situation. For example, part of our cognitive heuristic is to identify fire as hot and to behave appropriately behaviourally by not, say, grasping the burning part of a log.

These abstractions are commonly perceived as essences, a collection of attributes which describe a discrete identity. This tendency in Western thought may be dated back to Plato’s idealism where he held that all things have an essence – a true idea or form which is unique and expresses its uniqueness in the universe. Aristotle, the student of Plato, carried this way of thinking forward suggesting that each thing has an essence which expresses its intrinsic nature; as we might perceive the soul of a thing as the individuality we apprehend through our modality of selective attention.

This habit of mind gives rise to essentialism, a cognitive behaviour which frames things as things-in-themselves. Stephan Fuchs scrutinises this extensively in his book ‘Against Essentialism: A Theory of Culture and Society’: “In analytical philosophy, essences are called ‘natural kinds’. Natural kinds are those to which terms and classifications refer when they are true and constant in all possible worlds (van Brakel 1992:255). These terms become what Kripke (1980:55) calls ‘rigid designators.’ Natural kinds are things-in-themselves, after they have reached their true state and unfolded their inherent potential. They cannot be imagined otherwise. The preferred logical mode in essentialism is necessity, worked out in formal syllogisms, deductions, definitions, tautologies, and the like. Natural kinds always exist, or seem to exist, independent of relationships, context, time, or observer. The properties of natural kinds are those that make a thing what it essentially is; the rest is ‘merely accidental,’ or contingent and historical.”

[ Fuchs S. (2001). Against essentialism : a theory of culture and society. Harvard University Press. Page 12]

Jacques-Philippe Leyens and colleagues, introduced the term ‘Infrahumanization’ as an elaboration of studies on ingroup favourtism which makes solid links between essentialism and infrahumanization phenomena (Leyens et al, 2000). Infrahumanization is distinct from classic ingroup bias; it requires meaningful categories mediate by ingroup identification and groups’ essentialisation (Demoulin, Leyens, Paladino et al., 2004).

The characterisation of strong identities seems to be intrinsically linked with dehumanisation processes such as infrahumanisation emphasizing differences and diminishing unity perceptions. People with a concern about the identity and community of their group, almost by definition, may be opposed to those of the other group. Named the ‘minimal group paradigm’, Leyens discusses how this might almost prevent people from accepting belonging to another group (Leyens, 2009).

Excerpts

Leyens, J. P., Paladino, P. M., Rodriguez-Torres, R., Vaes, J., Demoulin, S., Rodriguez-Perez, A., et al. (2000). The emotional side of prejudice: The attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 186–197.

Demoulin, S., Rodriguez-Torres, R. T., Rodriguez-Perez, A. P., Vaes, J., Paladino, M. P., Gaunt, R., et al. (2004). Emotional prejudice can lead to infrahumanization. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (Vol. 15, pp. 259–296). Chichester: Wiley.

Leyens, J.-P. (2009). Retrospective and Prospective Thoughts About Infrahumanization. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12(6), 807–817. doi:10.1177/1368430209347330

How essentialism operates within our psychology is important to examine as through such a modality ideas can offer themselves as concrete realities when no such cogency exists. We can be in the grip of ideas which do not correspond to the actualities of the world around.

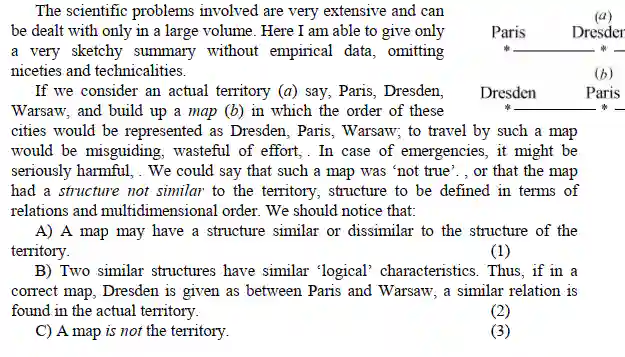

An array of forms of cognitive bias have been enumerated over the years which illustrate how perception can bend to wrong conclusions (See the overview of the textbook Bias’ and Heuristics; The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement edited by Gilovich, Griffin and Kahneman below). The notion that when something is clear in one’s mind, the thing which is represented is understood is a point of failure; as we will return to later in this work, Alfred Korzybski would argue it is important to realise ‘the map is not the territory’.

Essentialist ideas may operate as placeholders for fluid; early stage; imperfectly formed; disordered; incoherent; not fully in existence; or incomplete schemes of thought (Medin & Ortony, 1989). This might offer an account of how essentialism could operate to confuse, obfuscate or mislead a person in the grip of a scheme of thought.

Excerpt

Medin, D. L., & Ortony, A. (1989). Psychological essentialism. In S. Vosniadou & A. Ortony (Eds.), Similarity and analogical reasoning (pp. 179-195). Cambridge University Press. https:// https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511529863.009

Thinking about how bias’ operate in the world today, an anecdote comes to mind of when I asked the scholar Dominique Tessier what she thought about racism in the UK and she said to me “it is not so much that I think that Britain is racist but prejudiced”. The subtleties and nuances of her thinking pushed me to dig deeper and find more profound accounts of social and historical realities – the result of which is some of the thinking I am rehearsing here. I am testing the premise that cognitive error is tied up with bias and prejudice.

Clearly, infrahumanization suggests a double social reality and divergence which produces obstacles for equity at different levels of exchange between groups (Demoulin, Cortes Pozo, & Leyens, 2016). Is the process of the way which experience of others is bundled up to produce impressions prone to engendering essentialised renderings that conform to bias ?

Excerpt

Stephanie Demoulin, Brezo Cortes Pozo, And Jacques-Philippe Leyens, (2016), ‘Infrahumanization: The Differential Interpretation of Primary and Secondary Emotions’ in. Intergroup Misunderstandings Impact of Divergent Social Realities, (editors) Stéphanie Demoulin, Jacques-Philippe Leyens, John F. Dovidio, London: Routledge. Page 154

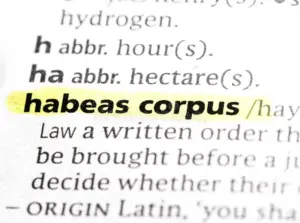

To tack into this issue, I find it helpful to break down the word ‘prejudice’ into its components in order to make clear the work which the language is doing: ‘pre’ is a prefix to a word meaning before, earlier than, prior to – and ‘judice’ a Latin phrase meaning “with me as judge” or “in my opinion”.

Putting this all together I find the construction of prejudice as ‘an opinion prior to judgment’ useful as I don’t perceive rational cognitive judgments being made in terms of prejudice; prejudices seem to be pre-made ‘heuristic’ templates which people carry around with them and use in order not to engage with some and to fetishise others.

An operational example might be how someone has decided that people who wear hooded tops are untrustworthy and so every time they encounter someone who is wearing one they will discount anything which contravenes their heuristic template in order to not engage with the person. One prejudice may be operational until another takes precedence; each individual bias need not necessarily be integral to the other, but the situational forces priming the individual may evoke different outcomes from the same person in different circumstance (Kofta, Baran, & Tarnowska, 2014).

Excerpt

“The infrahumanization phenomenon has been demonstrated on both explicit and implicit measures (e.g., Gaunt, Leyens, & Demoulin, 2002). Moreover, when an actor expressed secondary emotions, it had a different impact on an observer’s responses depending on whether these emotions were shown by an ingroup or an outgroup member (Vaes, Paladino, Castelli, Leyens, & Giovanni, 2003). When an ingroup member expressed secondary emotions, this increased the recipient’s implicit conformity (to the actor’s suggestions), made her or his linguistic behavior more prosocial, andstimulated an automatic motor approach response. However, when an outgroup member did exactly the same thing, the opposite effects emerged (Vaes et al., 2003).”

Kofta, M., Baran, T., & Tarnowska, M. (2014). Dehumanization as a denial of human potentials: The naive theory of humanity perspective. In P. G. Bain, J. Vaes, & J.-P. Leyens (Eds.), Humanness and dehumanization (pp. 256–275). Psychology Press. Page 256

You need not do radical things in order to observe the kind of thinking and values at play in the social configuration of Britain, you need only change the clothes you wear and make notes on how people engage with you, who will engage with you and what opportunities are open to you.

When I changed my dress from a Harris Tweed and cords to a brand-less coat and jogging bottoms the sociological differences were marked, it was as if I had stepped into another universe; I found that different people speak to me in different clothes, and in different ways – it is the minority of people who seem to be unaffected by my aesthetic appearance.

Harold Garfinkel described this as a Breaching Experiment; an experiment which has the aim to examine people’s reactions to violations of commonly accepted social rules or norms. Breaching experiments are common tools associated with ethnomethodology in order to understand cultures.

In ‘More Human: Individuation in the 21st Century’, Jillian K. Swencionis and Susan T. Fiske state “Influential models of impression formation suggest that humans are relentless categorizers: when meeting new people, unless we are otherwise motivated, we fit them into a category and create expectations accordingly (Brewer, 1988; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990; Srull & Wyer, 1989). Following these models, a vast literature on social categorization has emerged, describing the motivations and processes involved in categorization and its numerous effects on behavior (Fiske & Taylor, in press; Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2000)” (Swencionis, & Fiske, 2014).

Extra References

Brewer. M. B. (1988). A dual process model of impression formation. In T. K. Srull & R. S. Wyer. Jr. (Eds.), Advances in social cognition: Vol. 1. A dual process model of impression formation (pp. 1-36). Hillsdale. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fiske. S. T. & Neuberg. S. L. (1990). A continuum model of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influence of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. In M. R Zanna (Ed.). Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 23, pp. 1-74). New York. NY: Academic Press.

Srull. T. K„ & Wyer, R. S.. Jr. (1989). Person memory and judgment. Psychological Review. 96. 58-83.

Fiske, S. T, & Taylor, S. E. (in press). Social cognition: From brains to culture. London, UK: Sage.

Macrae. C. N.. & Bodenhausen. G. V. (2000). Social cognition: Thinking categorically about others. Annual Review of Psychology. 51. 93-120.

Social categorisations are of particular interest in understanding the mental processes which shape engagement or disengagement. Swencionis and Fiske examine Brewer’s (1988; Brewer & Feinstein, 1999) dual-process model of impression formation which differentiates between category-based and person-based processing but conceives of these as separate impression formation processes.

The model suggests that a particular trait can activate either knowledge about a category or knowledge about a person, but not both at the same time. In addition, Brewer’s model states that individuation (the mental process of humanising a person beyond a heuristic stereotype) can occur in either the category-based or person-based processing mode; in this view, individuation means more effortful, controlled processing of either category-based or person-based information. Although not explicitly so, this model also tends to give preference to category-based over person-based processing.

Excerpts

Brewer. M. B. (1988). A dual process model of impression formation. In T. K. Srull & R. S. Wyer. Jr. (Eds.), Advances in social cognition: Vol. 1. A dual process model of impression formation (pp. 1-36). Hillsdale. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Page 30

Brewer. M. B.. & Feinstein. A. S. H. (1999). Dual processes in the cognitive representation of persons and social categories. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.). Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 255-270). New York. NY: Guilford Press.

In their study of ‘Dehumanization as a Denial of Human Potentials’ Mirolaw Kofta, Tomasz Baran, and Monika Tarnowska also pick up on dual process models of perceptual attribution (Kofta, Baran, & Tarnowska, 2014). Picking up on Roland Deutsch and Fritz Strack’s work on ‘Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior’ (Deutsch & Strack, 2006) they look at evidence for how the human mind might operate in two qualitatively different ways which they describe as impulsive and reflective.

The impulsive mode is suggested to be closely related to the automatic activation of mental associations on the basis of feature similarity and contiguity (associative processes). This modality of parsing experience involves more reliance on mental heuristics which have been encoded through socially constructed experience and assertion of patterns. The reflective mode they suggest as related to a process of validation where activated information is parsed on the basis of logical consistency (propositional process).

These systems involved in perception formation operate differently. The impulsive mode (associative processes) functions in fast automatic processing of encounters in what might be understood as gut instincts that give rise to spontaneous inferences. The reflective mode (propositional process) works more slowly taking into account more time distant perspectives and involving a reasoned analysis which accords to values, norms, ideologies, belief systems, as well as notions of feasibility and desirability.

References

Kofta, M., Baran, T., & Tarnowska, M. (2014). Dehumanization as a denial of human potentials: The naive theory of humanity perspective. In P. G. Bain, J. Vaes, & J.-P. Leyens (Eds.), Humanness and dehumanization (pp. 256–275). Psychology Press.

Deutsch, R., & Strack, F. (2006). Duality models in social psychology. Psychological Inquiry, 17, 166–172

In their work Kofta, Baran, and Tarnowska (2014) explore how the naïve theory of humanity might inform accounts of dehumanisation psychology which denies the attribution of traits and characteristics to individuals who fit into target outgroups. Wegener and Petty (1998) give accounts of “naïve theories” as being related to similar notions such as common sense, lay beliefs, intuitive theories, and implicit theories.

They suggest that when people are responding impulsively, people may deny the humanity of another person based on a perceptual cue such as skin colour, gender etc but this judgment may be corrected in line with activated attitudes, values and normative structures which relate into the situation humanized awarenesses.

To add to this there is evidence for an available-resource dimension to perception which may influence which mode of perception is utilised in a given situation. The different modes entail different energy spends in terms of information processing. The work of Loughnan, Haslam and Kashima (2009) emphasises the importance of the more reflective, “capacity-consuming” processing. They detail how groups may be stereotyped in ways that are dehumanizing (for example, lacking human uniqueness), and this may lead to the inference of dehumanizing metaphors (for example, being animals).

Abstract

Wegener, Duane & Petty, Richard. (1998). The Naive Scientist Revisited: Naive Theories and Social Judgment. Social Cognition. 16. 1-7. 10.1521/soco.1998.16.1.1.

Loughnan, S., Haslam, N., & Kashima, Y. (2009). Understanding the relationship between attribute-based and metaphor-based dehumanization. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 12, 747–762.

The reverse could also be feasible as a scheme where the perceptual cue may offer some signal consonant with appreciated signals of humanness but where a reasoning process is engaged in order to deny the target of their humanness. Swencionis and Fiske (2014) suggest that categorizing acts as a shortcut to create coherence by the more labor intensive process of individuating people. In a related way encountering unexpected behaviours may prompt more thorough attributional processing; an effort generally associated with the individuating process. The unexpected also results in another process linked with individuation perception, as it prompts more thorough causal reasoning to be engaged with.

Relatedly, unexpected behaviors result in more thorough attributional processing (Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1981) and more thorough causal reasoning (Kunda, Miller, & Claire, 1990). Categorising people with stereotype notions is a way which people can use to create coherence in their mental schema; alternatively this can be done when people do not fit the category/stereotype/heuristic via more effort involving individuating processes.

Neuroscience studies have offered evidence to support the idea that inconsistent targets promote coherence-seeking goals and vurther individual level processing. Neural activity associated with reinforcement-learning apparatus (caudate and putamen) was noted in relation to violation of social expectations. Additional evidence has been found demonstrating neural activity associated with social cognition (medial prefrontal cortex) and domain-general conflict monitoring (posterior medial frontal cortex and right prefrontal cortex) is triggered when trait inconsistencies are encountered.

Social motivations for individuating people play a role in perceptions and behavioural outcomes. In their study Fiske, Lin, and Neuberg (1999) demonstrated that core social motives (belonging, understanding, self-enhancing, and trusting) are key influences in determining the extent to which we individuate another person. Research has consistently found that when another person has control over what will happen to us, we are more likely to engage in psychological individuating processes of impression formation in order to understand the intentions of the other person (Erber & Fiske, 1984; Neuberg & Fiske, 1987).

Seeing another person as more human functions to fulfill a range of social goals: Better understanding another person might help us in the attempt to belong to a group, to control what will happen to us, to maintain self-esteem, to improve ourselves within a social context or to develop trust with someone. As Swencionis and Fiske put it “we individuate others on whom we depend”. Generally, the more desirable a reward, the more positively biased evaluations of the target of the perception take place (Clark & Wegener, 2008; cf. Goodwin, Fiske, Rosen, & Rosenthal, 2002; Stevens & Fiske, 2000).

References

Pyszczynski. T. A.. & Greenberg, J. (1981). Role of disconfirmed expectancies in the instigation of attributional processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 40. 31-38.)

Erber, R., & Fiske, S. T. (1984). Outcome dependency and attention to inconsistent information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 709–726.

Neuberg, S. L., & Fiske, S. T. (1987). Motivational influences on impression formation: Outcome dependency, accuracy-driven attention, and individuating processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 431–444.

Clark, J. K., & Wegener, D. T. (2008). Unpacking outcome dependency: Differentiating effects of dependency and outcome desirability on the processing of goal-relevant information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 586–599.

Goodwin, S. A., Fiske, S. T., Rosen, L. D., & Rosenthal, A. M. (2002). The eye of the beholder: Romantic goals and impression biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 232–241.

Stevens, L. E., & Fiske, S. T. (2000). Motivated impressions of a powerholder: Accuracy under task dependency and misperception under evaluative dependency. Personalityand Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 907–922

Neuberg, S. L., & Fiske, S. T. (1987). Motivational influences on impression formation: Outcome dependency, accuracy-driven attention, and individuating processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 431–444.

Prejudice and not just stereotypes can affect how people individuate others, or not. Sherman et al (2005) did work examining how people who exhibited high levels of prejudice paid more attention to, and demonstrated better recall for, stereotype-inconsistent versus stereotype-consistent information in contrast to people who displayed low and moderate levels of prejudice. Swencionis and Fiske (2014) suggest that high-prejudice participants paid more attention to the non-stereotypic information in order to discount it and avoid individuating the subjects of their attention, instead ascribing stereotype-inconsistent information to situational factors.

Whilst low and moderate prejudice participants demonstrated similarly high recall for stereotypic and nonstereotypic information, high prejudice participants gave over more attention to the nonstereotypic information because it did not fit with their prejudiced views and actively sought to explain it away. This work provides evidence bases which could contribute to understanding the cognitive dynamics of a sort of pragmatic pessimism which underpins bias and prejudice as a mechanism of closing down cognitive dissonance that occurs between perceptual moorings of logical equity (i.e. egalitarianism regarding all people as similarly human) and idiosyncratic exceptionalism (i.e. elitism regarding people as more human than others).

Excerpt

Sherman, J. W., Stroessner, S. J., Conrey, F. R., & Azam, O. A. (2005). Prejudice and stereotype maintenance processes: Attention, attribution, and individuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 607–622.

Investigating the Structure of Thought

Beyond the parochialism of the Matryoshka class and subcults of Edinburgh in the theatre that plays out in how someone sounds their vowels or regards a piece of music, my interests extend into the ritual and tribal millieu of kith and kin which throws out a shadow like Meno’s paradox as to who belongs or who is an imposter.

What I mean by this is my interests have become focused on how people can be captured by the view that the outsider is ever unknowable and unrelatable with via a series of mechanisms used to shore up their conclusions as reasonable. I think that the converse can also be true too, that some people view some others as ever relatable – as ever familial – whatever their behaviours, whatever their deeds, whatever their values.

I think that there are structures in play in our psychology which act as heuristic templates that prime us to see what is happening in our environment in a particular way. Psychological structures could be understood as patterns of thinking that act as complexes –

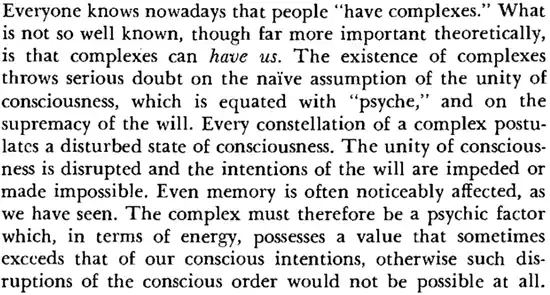

Carl Jung discussed, amongst other things, the autonomy and unity of the human consciousness: “Everyone knows nowadays that people ‘have complexes.’ What is not so well known, though far more important theoretically, is that complexes can have us. The existence of complexes throws serious doubt on the naïve assumption of the unity of consciousness, which is equated with ‘psyche’, and on the supremacy of the will.” (Jung, 2014)

Excerpt

Jung C. G. (2014). Collected Works of C.G. Jung the First Complete English Edition of the Works of C.G. Jung. ROUTLEDGE. Page 3052

This idea formulated by Jung speaks to how we can be in the grip of ideas and habits. When primed with a particular ingroup-outgroup bias people can attribute an identity to someone without necessarily knowing what the reality of the identity they have attributed means; in effect, the person is looking for something they do not know or understand, all they know is that some intuition has attributed a sense that the other does not hold the desired values or qualities.

These fictional identities – that is identities which have been constructed and attributed to others without reality checking – can then proove incorrigible when cognitive resources are not given over to checking and correcting impressions; this might be even more the case when the ideas associated with the fictional identities are not falsifiable (for example, situations of hearsay or dogma).

A suspicion I have is that in situations where someone has it in their head that they know the real identity of another person but are cynically bound to stereotypes or negative ideas, the mind can get caught in a mechanism of self fulfillment related in form to Zeno’s arrow paradox. Although the target person may exhibit evidence which does not fit the stereotype to which they are being held against, the perceiver may dismiss evidence to the contrary in order to pragmatically wait for proofs which they can use to justify the stereotype which is being fitted.

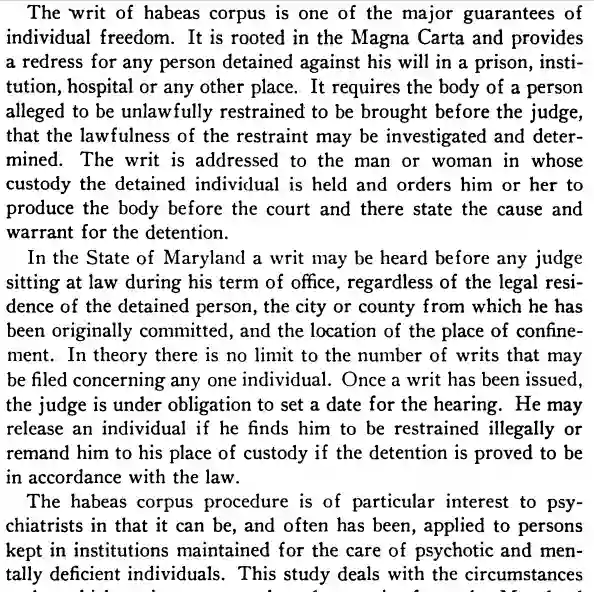

Such an account of cynicism must take into account the ideas that perceivers can be aware of their prejudice or unaware they are acting under the influence of some implicit bias. Into this exploration I am going to bring the notion of autonomy picking up on Jung’s point that “complexes can have us”. In their ‘Principles of Biomedical Ethics’ Tom Beauchamp and James Childress discuss autonomy in relation to patient rights:

“Some writers maintain that autonomy is a matter of having the capacity to reflectively control and identify with one’s basic (first-order) desires or preferences through higher-level (second-order) desires or preferences [2]. For example, an alcoholic may haave a desire to drink, but also a higher-order desire to stop drinking. An autonomous person, in this account, is one who has the capcity to rationally accept, identify with , or repudiate a lower-order desire independently of others’ manipulation of that desire. Such acceptance or repudiation of first order desires at the higher level (that is, the capacity to change one’s preference structure) constitutes autonomy.

Serious problems confront this theory. Acceptance or repudiation of a desire can be motivated by an overriding desire that is simply stronger, not more rational or autonomous. Second-order desires can be caused by ptoent first-order desires or by a condition such as alcohol addiction that is antithetical to autonomy. If second-order desires (decisions, volitiions, etc) are generated by prior desires or commitments, then the process of identifying with one desire rather than another does not distinguish autonomy from nonautonomy. The second-order desires would not be significantly different from first-order desires.

This theory needs more than a convincing account of second-order preferences: It needs a way for ordinary persons to qualify as deserving respect for their autonomy, even when they have not reflected on their preferences at a higher level. Few choosers, and also few chocies, would be autonomous if held to the standards of higher-order reflection in this theory…”

Page 58, Beauchamp T. L. & Childress J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Beauchamp and Childress reference Gerald Dworkin’s ‘The Theory and Practice of Autonomy’ in this section. For the reader I have included the preface and first chapter as a primer for learning and discussion. Whilst there are debates over how to identify where autonomy begins and finishes in personhood, it is clear that people at various points in their lives do certain things unthinkingly; it is in this unthinking space that I am going to position the next part of the scheme of thought I am looking at.

When we are not engaging in reflective, critical and self-critical thinking we are more open to automated behaviour. An examination of automated behaviour includes a large array of considerations which include situational forces, language and available cognitive resources. Philip Zimbardo is famous for writing about the role which context and situational forces have on behaviour and choices (Zimbardo, 2007).

Most well known for his Stanford Prison experiment, he went on to serve as an expert witness in defense of Ivan Frederick, a staff sergeant who was the highest-ranking officer court-martialed for the crimes at the Iraqi prison. As a psychologist Zimbardo lobbies for a greater understanding of how evil systems subvert good people, and part of how this occurs might be the language which is used, the clothes which are worn and the ideas which are held in mind when approaching others (for those interested in his write up of the social psychology involved see his book ‘The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil).

Video

Zimbardo P. G. (2007). The lucifer effect : understanding how good people turn evil. Random House.

For the purposes of my research and study my focus is particularly on the notion of how we are psychologically primed by various information and patterns which gives rise to higher likelihoods of given outcomes. There are is a great deal of research on this for example ‘structural priming’ in the field of psycholinguistics. Priming is the idea in psychology that exposure to one stimulus influences how we respond to a subsequent stimulus, without conscious guidance or focused intention.

Syntactic priming accounts for the way that our mere exposure to certain words primes us affecting how we remember and what information we pick out of subsequent situations: “The probability of a particular syntactic form being used in the description increased when that form had occurred in the prime, under presentation conditions that minimized subjects’ attention to their speech, to the syntactic features of the priming sentences, and to connections between the priming sentences and the subsequent pictures” (Bock, 1986).

Bock, J.K. (1986). Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology, 18, 355-387

Priming is used as a technique in Neurolinguistic Programming and marketing. As a practice it is controversial because it is considered to by some to be manipulative. Priming nevertheless happens and is a function of our psychological awareness; the structure of our experience shapes what we recognise in our environment and the choices we make within it.

Stripping this down to basic terms, it could be argued that our psychology is significantly composed of pattern recognition. We encounter the world through our senses and identify structure within that information which has meaning through context. We map our experience by creating mental maps as representations of the world in order to help us navigate future choices via having a range of references which allow us to make comparisons.

We develop language through generating symbols and asigning structured meaning to them that signal similarity to previous incidence. As we go through the world taking in the details of our environment, phenomena which have structured meaning trigger associations which have been made in memory that add information to the context in order for us to pick out what might be the best course of action in terms of appropriateness.

Through language humans have developed a complex system of information storage based on interrelations which allows information transmission outside of the concrete context to another person. Information as a result primes us to become aware of something in our environment offering maps composed of signs which signify a given phenomenon.

It can be argued that part of our being is not autonomous but reacts consequently to the environs beyond our individual biological body and physical carraige. For example, when we witness someone stub their toe, we ourselves might experience a sort of sensory surrogate as our nervous system reacts. We may react to ideas that have become operational via the associations which have been made, and the ideas may not even be based on a concrete reality; for example the common fear children experience that monsters may be under the bed.

The maps we create of experience are impressions of complex and messy phenomena. These maps we make of experience often get confused for the reality itself. This is nicely demonstrated by the work of Benoit Mandelbrot, the mathematician who is famous for discovering fractals. In his book ‘A Mathematician Plays The Market’, John Allen Paulos uses Mandelbrot’s thinking to illustrate the difference between what happens in the world and the images we have in our minds of the world:

“In general, fractals are curves, surfaces, or higher dimensional objects that contain more, but similar,complexity the closer one looks. A shoreline, to cite a classic example, has a characteristic jagged shape at whatever scale we draw it; that is, whether we use satellite photos to sketch the whole coast, map it on a fine scale by walking along some small section of it, or examine a few inches of it through a magnifying glass. The surface of the mountain looks roughly the same whether seen from a height of 200 feet by a giant or close up by an insect.

The branching of a tree appears the same to us as it does to birds, or even to worms or fungi in the idealized limiting case of infinite branching. As the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, the discoverer of fractals, has famously written, ‘Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line’. These and many other shapes in nature are near fractals,having characteristic zigzags, push-pulls, bump-dents at almost every size scale, greater magnification yielding similar but ever more complicated convolutions. And the bottom line, or, in this case, the bottom fractal, for stocks?

By starting with the basic up-down-up and down-updown patterns of a stock’s possible movements, continually replacing each of these patterns’ three segments with smaller versions of one of the basic patterns chosen at random, and then altering the spikiness of the patterns to reflect changes in the stock’s volatility, Mandelbrot has constructed what he calls multifractal ‘forgeries’. The forgeries are patterns of price movement whose general look is indistinguishable from that of real stock price movements. In contrast, more conventional assumptions about price movements, say those of a strict random-walk theorist, lead to patterns that are noticeably different from real price movements.” (Paulos, 2004)

Paulos J. A. (2004). A mathematician plays the stock market (Paperback). Basic Books. Page 174

Another mathematician illustrates how we learn from patterns. In his ‘Didactical Phenomenology Of Mathematical Structures’, Hans Freudenthal details his thesis of how structures infer understandings. For me these thinkers can lend something to accounts of the internal dynamics of inductive thinking active in our perception. This could go some way to accounting for how perception might be primed by a pattern (an idea) and how that pattern can go on to structure reality by becoming a lense through which other things are seen or unseen.

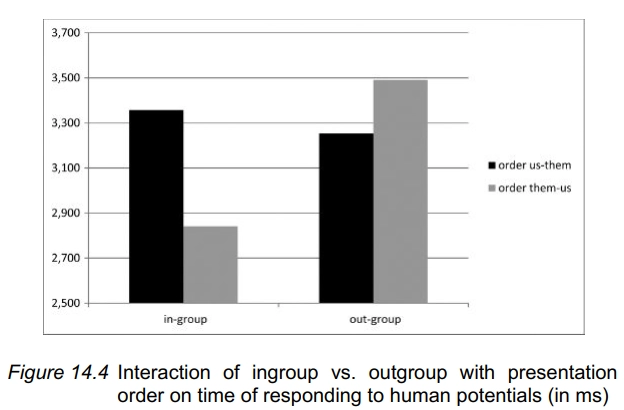

Returning to the work of (Kofta, Baran, & Tarnowska, 2014) – their chapter on ‘Dehumanization as a Denial of Human Potentials’ (which we touched on above) revealed an interesting phenomenon in their major findings. They reported the usual ingroup favouritism showing that when compared to outgroup members, more positive and fewer negative traits were ascribed to ingroup members; they also found that a greater number of human potentials were ascribed to the “us” category where decisions were made faster than to the “them” category which involved a slower decision making process. What stood out was the fact that order of presentation played a role in decision making outcome:

“The latter analysis also revealed an interesting interaction between social categorization and presentation order: The effect of ingroup-outgroup emerged for them-us order, not for the reverse order (see Figure 14.4). Thus, faster ascriptions of human potentials to the ingroup emerged only when participants first evaluated human potentials in the outgroup and then moved to the ingroup. This interesting pattern might suggest that people are more sure of their own group’s superiority on human potentials when they make a comparative judgment”

Excerpt

Kofta, M., Baran, T., & Tarnowska, M. (2014). Dehumanization as a denial of human potentials: The naive theory of humanity perspective. In P. G. Bain, J. Vaes, & J.-P. Leyens (Eds.), Humanness and dehumanization (pp. 256–275). Psychology Press. Page 264

In the second part of this article I share an essay which I submitted as a part of the masters degree I am doing which involves Public Sociology in relation to Mad Studies. It reflects on what I am calling ‘the Identitarian Problem’ in the context of Mad Studies – an academic discipline which has emerged from the fundamental failures of the psychiatric-medical-societal responses to psychological wellbeing and representation.

Section Two:

Mad Studies: The Identitarian Problem

Introduction

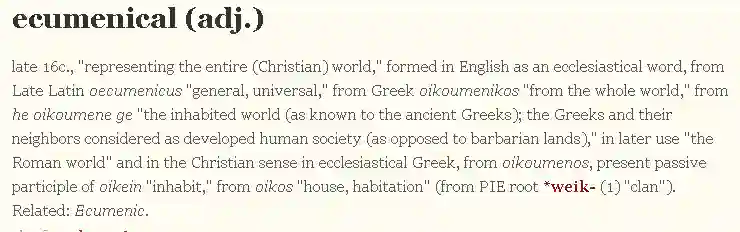

In this essay I am responding to the issue of conflict within the field of Mad Studies and a corresponding need for an ecumenical framework if it is to function to represent marginalised voices. I argue that this is needed for Mad Studies to function as a mechanism to acknowledge and afford dissonance within the field as it makes the same demands of psychiatry.

I suggest there is what I call an ‘Identitarian Problem’ at work generated through, and generating, ingroup/outgroup behaviours of typology utilised as means to create margins and marginalized. This work attempts to rationalize the territorialism of humans in communities, understand the hostilities which arise through identities based on differentiation, and notionalise a mitigating strategy in order to represent the unheard.

A Working Definition for the field of Psychiatry

In this section I examine group dynamics of marginalisation citing within this what I call ‘the Identitarian Problem’. By naming this as a strategy I attempt to set out the kind of ecumenical space of amnesty required for non-imposition and respect for autonomy of perspective. Mad Studies is necessarily a holistic field which is associated with the plurivocal (Bager and Mølholm, 2019).

Abstract

Bager, A. S; Mølholm, M., (2019). A Methodological Framework for Organizational Discourse Activism: an Ethics of Dispositif and Dialogue. Philosophy of Management

Without such a strategy to resolve calls to dominate and colonize difference, the identitarian problem will prevent transcultural engagement across intersecting spectrums of reality. This happens not only in Mad Studies but also within psychiatry and medicine. As a consequence the culture becomes stranded from the means of transcending the double binding (Bateson, Jackson, Haley, & Weakland, 1956) negatives of otherness.

Excerpt

Bateson, G., Jackson, D.D., Haley, J. and Weakland, J. (1956), Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Syst. Res., 1: 251-264.

As my work and research has progressed over time I have had to take on and include new perspectives in an evolving working definition of psychiatry which is as follows: “There is a global questioning of psychiatry and the vertical power of orthodox institution of medicine as responses to the experience of people with a variety of ailments of mood, cognition and behaviour. People for differing, overlapping and changing reasons seek out a therapeutic response to distress they experience. Medical intervention can also be imposed as a carceral response due to someone, a group of people, or a cultural apparatus, deeming their behaviour, thought and or mood unfitting.

There are abuses of power and there are abuses of psychiatric power; there are virtuous exercises of power and there are virtuous exercises of psychiatric power. There are systems effects active in between articles of faith and axes of scepticism at work. Power dynamics arise around membership in groups as identities which are policed by dominating proponents positioning individuals outside the group membership as having fewer rights to representation”.

I have pulled together this working definition in order to bring into relief some account of the focus of attention when we are dealing with mental health/mental illness. Language and definition are imperatives in the process of discussing, documenting, researching and developing knowledge. Whilst I have found the above qualifiers for description as necessary for inclusion, they are not sufficient.

As well as this issues arise of non-uniformity and non-consonance within the subject field. Like attempting to describe non-linear concepts with linear language, the above definition is neither broad nor specific enough to be useful in uniting the proponents of Mad Studies. It may incorporate necessary qualifiers for some but it does not offer sufficient explanatory power to account for all realities which factor into the field. The conflict at work acts to divide a transcultural impulse to interrogate and challenge how mental illness/mental health is perceived and responded to. In the next section I will examine how the field of Mad Studies contrasts with psychiatry.

The Purposive Definition of Mad Studies

I take as my starting point the purposive definition below of Mad Studies which David Reville (2023) offers in using the exemplar of a picture of the physician Charcot with a woman, ‘Blanche’, held in his arms before a room of physicians:

“It’s easy to get to La Salpetriere, it’s a short walk from La Gare d’Austerlitz and across from Le Jardin des Plantes; it’s on the Boulevard de l’Hopital. On the grounds you’re gonna come across a big plaque and on the plaque is a painting of Charcot giving one of his famous lectures. If you look at the plaque you’ll see that there are about twenty serious looking men paying close attention to the Master. And as I look at the painting, the person I want to know about of course, is not J.M. Charcot, it’s Blanche. Blanche is the prop that Charcot is using in his lecture, she’s a young woman who’s said to have hysteria, she has her head thrown back, she’s being supported from behind, there’s a nurse standing by. That’s the difference between the history of psychiatry and Mad People’s history. The history of psychiatry is about Charcot, Mad People’s history is about Blanche and it’s Blanche we don’t get to hear”.

This purposive (defining a function) rather than nominative (defining a group) descriptor of the subject field of Mad Studies offers a compass to navigate unmapped terrain. Reville’s definition is useful both in the mythological sense of where maps end (‘there be dragons’ – the magical thinking associated with fear of the unknown), but also in the sense of those things lost in the imaginary of the cypher. To explore this I draw on Korzypski’s the ‘map is not the territory’ to illustrate Blanche is not the ‘hysteria’, the rubric is not the ailment, and the cypher is not the person. I will return to this metaphor later.

Mad Studies as a disciplinary field has emerged in part as a reaction to the psychiatric enclave of the western orthodox medical establishment which has produced categories of ailments which affect the psyche. As well as this it involves the reaction to pharmaceutical and carceral interventions developed.

Critical in this field of knowledge is the inherent disagreement over the nature of disturbances of the psyche. Part of the problem of the categorical approach (medical rubric) is due to the psyche being non-uniform in its nature; the ways in which the psyche can be understood and affected are more diverse than the human environs in which they develop. The subject disciplines of Mad Studies, psychiatry and psychology are non-homogeneous therefore need to represent this.

Forms of Identity Operating within Mad Studies

In this section I lay out some constructs which structure identities from key positions to illustrate the non-uniformity which the field has to reflect in order to be authentic. One position in Mad Studies may share some of the principle values of the medical institution in that a ‘healing’ response is sought by an individual to ailment they experience (Kings College London, 2016).

For an annotated transcript CLICK HERE

For example, the experience of chronic acute anxiety disrupting cognitive and behavioural functioning in the world or memory loss may instigate an individual seeking out possible remedies from a medic. In Mad Studies however, there may be radical differences in perspective of what response and rubric is appropriate; a Mad Studies account may highlight the inherent knowledge and understanding of the Principal (person receiving the attentions of the doctor) as being more useful in responding to what ails them than that of the Agent (doctor responding to the individual through the medical rubric) (Gormley and Balla, 2017) (See Appendix).

Gormley, W. T., Balla, S. (2017) ‘Bureaucracy and Democracy; Accountability and Performance’ Third Edition, CQ Press College, ISBN-13: 978- 1608717170, Page 72 – 75

Another position active in Mad Studies may share the principle found within faith communities such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses in that they reject medical intervention (Russo, 2022; Smith, 1995). This includes notions that every reality is rooted in the non-material and that the material is manifested through ‘spirit’. Examples might include the rejection of blood transfusions in favour of prayer to a deity or similar actions banking on ideas that illness is generated as a result of ill-thought or incorrect action in a previous life.

Excerpt and clarifying comment

RUSSO, J., (2022) De-psychiatrizing our own research work. Front. Sociol. 7:929056. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2022.929056

Clarifying commentary: My take is that Russo’s work is doing vital work in highlighting how social and sociological problems are being obfuscated via the dominant privilege of the medical model of mental illness. This is certainly the case and whilst sociological living conditions for populations in Britain (for example) are plummeting through the ravages of exploitative finance and brutalising working conditions (for example). I argue that to not acknowledge the reality that material harms can emerge from social/structural violence (etc), and the realities that toxicological harms can affect the mood, cognition and behaviour of people (i.e. harms from drugs, pesticides, pollution and heavy metals etc) is to fail to recognise an essential factor in the mental well being of humans. In the context of this writing, it is to artificially reduce mental health/illness to a dualistic political struggle between material and non-material causes framing the realities of people to an either/or scenario which is unrepresentative of what is happening in the universe. This is to seek to reproduce the hegemony of the medical institution with a successive countervailing hegemony of social institution. The medical institution fails to grapple with the toxicological harms which populations face, commonly with prescription drugs, but more significantly with public health matters such as air pollution, mercury amalgam fillings and organophosphate poisoning; the industrial-medical complex as it stands also fails significantly to acknowledge the harms which are produced by the degenerative social conditions brought about by the sociological configurations built and maintained by the political/financial classes via various forms of artificial scarcity and autocratic governance. Analogously, if a social and civil position rejects that there can be any material factors to consciousness and wellbeing it is to obfuscate evidence bases which show that degenerated food chains, xenobiotics and a range of other medical realities can be factors (i.e. toxoplasmosis) that manifest as legitimate psychiatric concerns. It is to ignore and de facto accept that our living world is being poisoned in measurable ways which affect us and seek to produce a dominance of the perspective that individuals and other people are solely and non-materially responsible for ailment; a political position which can be utilised in the neoliberal paradigm. Pragmatically this position amounts to the same semiotics (signs and signifiers) as a sort of secularised faith healing that shares elements with religious perspectives that account for all illness via disruptions in the spiritual/non-material (a realm which traditionally has been placed above nature/materiality rather than in it). As the reader will see in the argument which follows, I argue that we need the capacity to draw from both perspectives of understanding embodiment, and that the material and non-material are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Excerpt

Smith, M., (1995), Ethical perspectives on Jehovah’s Witnesses’ refusal of blood, Staff bioethicist and vice-chair of the Ethics Committee at the Cleveland Clinic. Since 1995 president of the Bioethics Network of Ohio https://www.ccjm.org/content/ccjom/64/9/475.full.pdf

Some hold not just a position of disagreement with the medical institution and rubric but a fundamental rejection of scientific knowledge in total. In the realm of different publics – big and small cultures, communities, networks and individuals – we see the interplay between perspectives of scepticism and dogma requiring an ethical approach. In a world which is contrastingly polycultural and polyvalent there is a necessity to realise a cosmopolitan ethic in order not to participate in the creation of new hegemonic colonialities by eclipsing people’s experience.

Reville’s open ended purposive definition of Mad Studies as the unheard emerges as a response to the colonial hegemonic of the medical institution. It is a space that values the importance of the plurivocal which is inherently dissonant as some positions are different in their character and in their relationship with the material-biological realm. To manufacture consensus and consent is to recreate the violence of the medical institution by the artificial curation of a we/they dichotomy of fact and silence (Trouillot and Carby, 2015).

Excerpt

Trouillot M.-R. & Carby H. V. (2015). Silencing the past: power and the production of history. Beacon Press. Page 27

Nominative Identities and Group Dynamics

Identitarian accounts of self and other offer category statements used as signifiers to create, curate and remake boundaries. These are used in part to constitute who is a member of an ingroup and who is not. The sociological denominators which define a particular group of members are used to shore up difference in order to consolidate the power of a group. This offers its members identity as a part of that power structure or tribe. Group dynamics occur within such sign and signifier systems of power through identity (Elias and Scotson, 2008).

Excerpt

Elias N. And Scotson J. L. (2008). The Established and the Outsiders. University College Dublin Press. Preface and Introduction (excerpt page xviii)

The identitarian problem has its roots in the fact that social mammals gain a range of benefits from being a part of a group. The natural sociological instincts are primed from an evolutionary pathway entwined and co-constituted with group living. In the formation of small and large cultures homophily is active as a social phenomenon – in simple terms, birds of a feather flock together (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). Social capital comes to people where group membership forms a resource that can be drawn upon as an enrichment. As social mammals, membership in a group or community can be understood as valuable in terms of the social mitigation of stress (Sapolsky, 1994).

Excerpts

Mcpherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Sapolsky R.M., (1994), ‘Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers’, W.H. Freeman and Company, New York Page 133

The first impulse might be homophily however there are shadow behaviours which arise to challenge cooperative impulses. Benefits of membership in a group offer a basis for territorialism and hostility to the possibility of outside threat. Ingroups and outgroups are formed around tenets which determine membership in groups. In my appendix I offer an autoethnographic vignette to illustrate this.

A group often takes forms which vociferous leading figures determine. People become members of groups often through informal, semi-formal and tacit acquiescence electing others to represent them as proxy and approximation of their experience. Membership in a group is sometimes more based on a social impulse than shared values.

Compliance with the group and avoidance of dissent are two of the signs (Deikman, 1990) of toxic group behaviour (Young, 2022, p.297). The devaluation of the outsider perspective is another. Just as we find these dynamics in groups of humans occupying symbolic and agencial roles in formal medicine we find similar dynamics in groups critical of psychiatry.

Excerpts

Deikman A. (1990). The wrong way home : uncovering the patterns of cult behavior in american society. Beacon Press. Excerpt: Page 154

Young D. M. (2022). Uncultured. St Martin’s Press. Page 297

The sociological dynamic which plays out is one of exclusion in a struggle to manufacture consent, or assent to a simplifying unison voice. The desire to engender compliance in the group to create a political structure causes people to diverge from their plural values in order to bolster a singularising aspect.

The group may be defined by identity checking and by its porosity to outsiders. The social modem of praise and blame gossip (Elias and Scotson, 2008) offers an archaic mechanism by which tribal identities form, police and remake themselves. Gossip might be considered the most simple of mechanisms which can serve to communicate indicators for include or exclude signals. Groups formed like this offer fixed nominative identities which can be used to create distinctions.

In a polyvocal, polyvalued space, there must be an appreciation – a valuation – of more than one single response to any point of contention. How in Mad Studies can there be philosophical provision for multiple perspectives in the face of the orthodox hegemony which has privileged a singularising perspective constructed of manufactured consensus? I use the term manufacturd specifically because the medical rubric is a result of vertical line management of medical responses and is not a reflection of the collected perspectives of people who act in roles of the orthodox medical institution.

Is what Mad Studies faces, the issue which human society wrestles with collectively in issues with adopting categorical responses? Do the instincts to form categorical responses threaten to subvert the true nature of Mad Studies as a field? Has the industry of psychiatry subverted the spirit of the medical healer?

When a singular response is manufactured a group ends up with a destruction of multiple viewpoints. The identitarian impulse devalues difference in order to make a pointed ‘win’ and transforms difference in order to consolidate its identity (Sherman, Stroessner, Conrey & Azam, 2005) – a position which can be charisma driven and oriented around a community rather than values. A community response can represent a political response where ‘winning’ promotes a strategic compliance. The social ordering of information into what work as policy statements is an homogenising process destructive of individuating outlier details.

Excerpt

Sherman, J. W., Stroessner, S. J., Conrey, F. R., & Azam, O. A. (2005). Prejudice and stereotype maintenance processes: Attention, attribution, and individuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 607–622.

Dualling Narratives: The Map is Not the Territory

Identities form in relation to political formations and are seen playing out in Mad Studies. Political as well as religious ideas play out to inform scientific and medical domains. Dualling narratives express themselves in sometimes dissonant mental accounts – sometimes consonant mental accounts – which act to reform the medic-patient (Principal-Agent) setting. In other words, the structure of a religious or political idea can appear in medical and scientific language.

Medicine is littered with articles of faith and self-referential accounts of phenomena. Dogmas embody themselves in the medical institution as secular reworkings of unquestioned beliefs (Deikman, 1990) as much as they do in Mad Studies. For example it is not uncommon for ailments to be ascribed genetic causality without adequate evidence for them being so; some medical diagnoses are asserted which lack material accounts of their causes (i.e. toxicologically), mechanisms of failure or sufficient scientific evidence for treatments. Psychiatry as a field is especially susceptible to such operationalised a-priori assumptions.

Excerpt

Deikman A. (1990). The wrong way home : uncovering the patterns of cult behavior in american society. Beacon Press. Page 110

The identitarian problem arises in situations where identity becomes fixed and nominative (rather than fluid and purposive); a percieved identity gives rise to categorical cyphers and stereotypes emerge to position other people (Fiske and Neuberg, 1990). This sets the scene for people being reacted to as cyphers of other people’s ideas. In psychiatry, the person is acted on through the pattern of the rubric; in communities critical of psychiatry people may be categorised according to their similarity to psychiatry and thereby be marginalised.

Excerpt

Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum model of impression formation, from category- based to individuating processes: Influence of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 23, pp. 1– 74). New York, NY: Academic Press.

The Identitarian Problem operates to take a single dimension of a complex phenomenon and decontextualise it. As a result this process obstructs real world engagement preventing the discovery of individuating characteristics (Kofta, Baran and Tarnowska, 2014). The urge to reduce everything to a singular essence causes everything to be perceived as ‘impure’ (dissimilar) when compared to the abstraction (category); a perception which can act as a charter for exclusion.

Excerpt

Kofta, M. Baran, T. And Tarnowska, M. (2014) Dehumanization as a Denial of Human Potentials; The Naive Theory of Humanity Perspective, In Bain, P. G. (2014). Humanness and dehumanization. New York: Psychology Press.

This essentialising reflex reduces and simplifies people to representations abstracted from individualising characteristics (Swencionis and Fiske, 2014). People are transformed to cyphers, derivatives of other people’s agendas (Cahill, 2011) and alienated from their own experience by dominating narrators/narratives in the process.

Excerpts