Black History: Implicit Bias, Dishonest Scholarship and Colonial Propaganda

This article is a result of researching the work Akala presented at the Oxford Student’s Union for Black History month. It is part of a series which comes from the researching of one section at a time using the online video as a knowledge resource to structure a self directed curriculum. This methodology is one which has been developed in order to facilitate independent learning especially in informal contexts of the lives of people like myself.

Table of Contents

Introduction

This article explores harsh subjects carrying a sense of pragmatic optimism that there is an increasing interest to learn about the past in clear and honest ways. It is not suggesting itself as an authoritative account but more presented as an example of exercising the skills associated with what we call scholarship. As an independent learner this is an artifact of learning which has come from efforts to understand more about a world I know relatively little about.

Akala

Text taken from Akala’s Oxford address: 1 min 5 sec to 2 min 43 sec

“If we think about a time just over 100 years ago when African human beings were literally kept in zoos in London, in New York, in Paris; that gives us a sense of the strength of colonial propaganda. It shows how deeply it had taken root in this society and others to the point that was actually argued by hard science by people who consider themselves serious academics that black people were more closely related to monkeys than to other human beings.

What we know, just as we can see today, that dishonest scholarship can be a tool for profitable foreign policy so is the case in the past. A lot of the time we’re led to believe that people actually believed the propaganda of the time

Those Scholars we’re talking about when we know just as we can see today, people have more knowledge about what’s going on in some country in Africa or Asia that we might be preparing to go to war with, so did they know more back then than we’re led to believe ?

There was no magical time when people who really had knowledge about the world didn’t know what was really going on on the ground; history was distorted deliberately in particular ways, and that legacy is still with us in many ways.

To the point that even for someone like me who I’d like to feel lots of my followers are socially engaged, know about the world when I post pictures I was in Zimbabwe a couple of weeks ago…

…this just gives you an example, when I post pictures of the capital city of Zimbabwe Harare and they’ve got skyscrapers and nice hotels and the Beautiful Jacaranda trees if you’ve ever been to Harare you’ll know this.

People are like ‘wow they’ve got skyscrapers in Africa’ – I don’t know if people think people in Africa still live in mud huts; and then if people believe, as you’re going to see over the next half an hour, if there was ever a time when everyone in Africa lived in mud Huts, but the strength of propaganda even for people of African origin is still with us to that point that we have this thing called Black History Month.”

African Human Beings Were Literally Kept in Zoos

“…If we think about a time just over 100 years ago when African human beings were literally kept in zoos in London, in New York, in Paris; that gives us a sense of the strength of colonial propaganda…” – Akala, Oxford address.

Unpacking the history of racism necessarily involves unpacking the history of knowledge; who gets to speak and whose words represent what happened. This in turn involves the unpacking of the ways which knowledge and ideas have been used in different ways; sometimes to support better understandings of what takes place in the universe, sometimes to argue in support of ideological stances. Recognising the ideological wars which are active within the human theatre of ideas is essential for anyone to remain focused on ‘what is’ rather than what someone thinks ‘ought to be’; or even what we are told was.

Ideas and bodies of knowledge can become adopted, appropriated and overlaid upon in support for different perspectives and world views. It is arguable that the behaviour of seeking evidence to support your own perspective on things is a natural behaviour inherent in the learning process which scholars of a subject train themselves not to do. There is plenty of evidence that our selective attention biases provide the foundations for the psychological distortion of the world as it is.

In the ebb and flow of ideological struggle we see knowledge and science appropriated by various camps to argue for various outcomes – ethical and unethical – and not uncommonly layered with inferences that promote the broader bases of world views. We can see how cultures drew on racist premises in order to bolster their political myths in the world through arguing for a particular sociological configuration such as so called claims of ‘white supremacy’; at the same time we can find arguments from within ‘white’ cultures (put in apostrophes to emphasise the lack of contiguity and homogeniety of sentiment and content) the equity of all peoples, but sometimes with the inflection that science has led to the immorality manifest in racism via theories of evolution.

Racism and prejudice have regularly featured as tools of political colonisation and dominance, and will continue to do so. This is partly what complicates the discourse surrounding arguments and ultimately brings in the necessity for discourse analysis in order to prevent the issues becoming territorialised in leading ways. Take for example the work of the Discovery Institute and the Center for Science and Culture. They have produced what is by all means a good documentary highlighting the history of Human Zoos – situations where people of colour were put on public display in order to create and curate an image of alternative cultures and peoples as ‘savage’.

When taking in the media it is important to understand the commissioning of the work and the way it is being contextualised in making other arguments. The Discovery Institute and the Center for Science and Culture are a conservative Christian think tank in the United States which lobbies for the inclusion of creationism in the form of intelligent design in public science curricula and attempts to cast doubt on the theory of evolution. As a result we can see examples of the use of the positioning of ‘scientific racism’ with an absence of religion.

This causes conflation of ideas of racism with the notion of evolution is problematic precisely because religious world views have also been factors in promoting racism and prejudice in times and places (as well as factors in arguing against). Whilst there are different world views vying for precedence of political myths, we cannot be distracted from the fact of a consensus that racism is a pathology that has and continues to produce degenerative harms in the world. At the same time, it must be recognised that in the narratives of Christianity and the stories of the Christ figure in the Gospels there are indisputably messages of equity and humanity for all.

These complexities lead to more complexities when we consider how the texts included in the Christian canons were set in geographic locations of cultures which were and are of colour. The notion of taking literally an historically Aryan Christ figure clashes with the material facts of history, archaelogy and other knowledge disciplines raising issues about such interpretations. There are considerable issues with interpreting religions in literal ways when many theologists point out the figurative nature of the content of writings.

Following the enlightenment period and the widespread publishing of science and scientific method that helped humans reason about their place in the universe, increasingly authority had to make an appeal to the universe (the facts) rather than to personality, charisma and superstition. As paradigm shifts took place, notions of authority based on evidence started to shape the politicisation of knowledge and initiate the reinvention of notions such as providence (The care, guardianship, and control exercised by a deity; divine direction) and ‘divine rights to rule’ (e.g. ‘The divine right of kings’). Old ideas became dressed in new language to account for the ‘truthiness’ of those things which established cultures caused to be true.

‘Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage’

Devised and edited by Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boetsch and Nanette Jacomijn Snoep and presented by Lilian Thuram, the book ‘Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage’ reveals and interrogates how racist ideologies found themselves dressed up as science – objectively established and tested knowledge which explained the order of things to peoples. What follows are some excerpts from this work:

Click to download introduction and chapter one

“Today it seems hard to understand how people could perceive, demean and display human beings like objects, and how that phenomenon could trigger such fascination over the centuries. From sordid to commercial – reaching the heights of indecency – human zoos, circuses, fairs, ethnic exhibits, freak shows and other spectacles staged the exploitation and dispossession of certain humans by other humans. They opened the door to realms of imagination that this exhibition masterfully reconstructs.

[Some images of the ‘Human Zoos’ which took place in major western cities. A related exercise Sylvia Federici suggests is to think about the individual who each has their own name, their family connections, their social communities, the richness of their internal worlds and meditate on what their visceral experience was in order to humanise those who have been dehumanised]

Ever since the Renaissance, non-Western civilizations have sparked curiosity and disgust, attraction and repulsion, with equal intensity. The many works on show in Human Zoos. The Invention of the Savage offer a journey through these “appearances” and provide a more subtle grasp of the arbitrary nature of ways of looking. Dotted with fascinating multimedia installations, the exhibition presents no fewer than five hundred items and documents – marshalling a wide spectrum of media to provide an accurate idea of how the “Other” was represented in all its complexity and diversity.

As Pascal Blanchard, one of the curators of the show, has aptly put it, “The entire period of human zoos corresponds to an absence of referents in the West with respect to alterities.” Indeed, it was an implicit question of “underscoring difference, of drawing an invisible line between normal and abnormal”, of thinking about the borderline between “us” and other individuals considered to be exotic, wild, or savage. Such wildness furthermore legitimized

This exhibition is the fruit of a meeting between Blanchard – a specialist in colonial history with its “fractures” – and French football star Lilian Thuram, who has lent his name, image and convictions to an operation designed to shed some light on this often overlooked aspect of a relatively recent past. My thanks go to both of them, as well as to Nanette Jacomijn Snoep, Curator Historical Collections at the Musee du Quai Branly, who put so much skill and courage into making this show a success.”

– Stéphane Martin

“Ever since I was a child, I have felt moved to question certain prejudices, and this questioning has led me to an interest in slavery, colonization, and the sociology, economics and history of racism. Ten years ago, thanks to Pascal Blanchard and the researchers working with him, I learned about human zoos. This was a revelation. I was surprised by the magnitude of this phenomenon which, over the years, developed into a mass culture. The images of these men, women and children – exposed and exhibited, shown and humiliated – appeared on postcards, posters, paintings, crockery and souvenirs. Looking at the films or photographs of the exhibitions, we see families strolling around, children smiling: happy spectators.

The public was at a show, denying the humanity of these people: the humanity of Saartjie Baartman in the early nineteenth century, of Ota Benga in the early twentieth, and of the great-grandparents of my friend and fellow-footballer Christian Karembeu, exhibited in the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris and in a German zoo, in 1931. All these stories are part of our common heritage. But they are still too little known. Much more remains to be written, shown, told, and passed on.

Knowledge of the human zoos helped me understand just that little bit better why certain racialist ideas continue to exist in societies like ours. For when I go into schools to talk about racism, children still do not know that there are not several different races, but just one species: Homo sapiens. How many people still think, consciously or unconsciously, that the colour of a person’s skin determines their qualities or faults? Do Blacks run faster? Do Whites swim faster?

Today, after two years of work and research, I think it is an extraordinary thing that the leading international specialists on human zoos, colonial exhibitions and world’s fairs, on the history of circuses, science and theatre, have contributed to this catalogue which helps us to better understand our present. They explain the racist prejudices, with their hierarchies and contempt, that live on in our society. These images that, yesterday, “invented the savage”, must today be used to deconstruct those patterns of thought which propagate the belief in the existence of types of human being that are superior to others.

Even today, for many communities, the best way of defining themselves is to oppose themselves to others: “They are like that and we are not.”

Are we not capable of enjoying self-esteem without denigrating the Other? The encounter with alterity may be sexual, cultural or religious, but it can also concern our partner, sister, brother, friend, son or daughter and should be a process of permanent negotiation. After all, are we not constantly negotiating with ourselves?”

– Lilian Thuram

“The exhibition Human Zoos. The Invention of the Savage and this accompanying catalogue reveal an incredible quantity of artworks and artefacts shedding light on the long historical process behind the fabrication of alterity and the “invention of the savage” over the centuries.

The Musee du Quai Branly, the Prado, the Louvre, the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelie, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the National Portrait Gallery and many other museums, libraries, universities and archives in Europe, Australia, Japan and the Americas, too numerous to be cited here, not to mention important private collections (like those of Gdrard Levy, of the ACHAC research group, and Michael Graham-Stewart), all hold traces of this incredible story.

Paintings, sculptures, posters, anamorphoses, casts made on live subjects, waxworks, automata, magic lanterns, costumes and masks, daguerreotypes, photographs, postcards, plates, fans, tablecloths, jigsaw puzzles, entrance tickets, brochures, advertising documents, films, songs, puppets, dioramas and all kinds of surprising souvenirs were identified throughout the preparation of the catalogue and exhibition and have been brought together for the first time in a single place, around one unifying theme, thereby taking on a completely different meaning.

Displayed in cabinets of curiosities, on the boards at fairs or in the street, kept in scientific laboratories or exhibited in a pavilion at a colonial exhibition or world’s fair – all these accessories from the “theatre of the world” contributed to the creation of these spectacles of difference.

It might be thought that these images show only anonymous individuals. But no, many of these “exhibits” have been identified; their names are known, as are the details of their highly varied and incredible destinies. Now that the cloak of anonymity has been lifted thanks to the research carried out over the last twenty years – notably by many of the contributors to this catalogue – it is at last possible to write the history of these exhibitions mounted on every continent.

By giving them a name, a life and a history, we free these people from the shackles in which they were once held, restoring dignity to individuals who suddenly found themselves thrust on stage in front of a curious crowd simply because they were considered different. Different because they were not the same colour or size; different because they came from faraway lands.

To discover and present this vast heritage for the first time, to bring it “into the museum”, to bestow tangible reality on this “living cabinet of curiosities of the world”, is to make them concretely a part of contemporary history. To tell that tale, to identify, analyze and decipher these testimonial objects, is to write the story of the construction of otherness and touch on a universal phenomenon. This varied, multiple heritage challenges us and invites us to position ourselves in this “theatre of the world” – either on stage, in the stalls, or in the wings.

– Nanette Jacomun Snoep

Colonial Propaganda and Dishonest Scholarship

“…It shows how deeply it had taken root in this society and others to the point that was actually argued by hard science by people who consider themselves serious academics that black people were more closely related to monkeys than to other human beings.

What we know, just as we can see today, that dishonest scholarship can be a tool for profitable foreign policy so is the case in the past. A lot of the time we’re led to believe that people actually believed the propaganda of the time

Those Scholars we’re talking about when we know just as we can see today, people have more knowledge about what’s going on in some country in Africa or Asia that we might be preparing to go to war with, so did they know more back then than we’re led to believe ?

There was no magical time when people who really had knowledge about the world didn’t know what was really going on on the ground; history was distorted deliberately in particular ways, and that legacy is still with us in many ways…”

– Akala Oxford Address

Such fictions were used in order to story imperial foreign policy of places such as Europe in an age when countries had started to have to confront their historical practices of going abroad and ravaging other cultures by brutal and inhumane force. Following the development and progress of knowledge sharing through media such as print, radio and photograph, these new and powerful aspects of human culture were used to create political myths that served the cognitive dissonance of colonizing cultures.

Below is an extract from a chapter of an excellent collection of work on dehumanisation psychology. In it Gustav Jahoda offers a historical account of the development of scientific racism noting some key figures and aspects of how it took form. The volume from which it is taken offers an overview of the rapid expansion of this area of psychology and sociology in recent decades covering not only the extreme manifestation of prejudice but also the everyday and intrinsic. It unfortunately seems that dehumanisation behaviours are more common than were previously recognised.

Excerpt: An Anthropological History of Dehumanization From Late-18th to Mid-20th Centuries by Gustav Jahoda

Jahoda, G., (2014), ‘An Anthropological History of Dehumanization From Late-18th to Mid-20th Centuries’ In Bain, P. G. (2014). Humanness and dehumanization. New York: Psychology Press.

The dehumanised way which peoples were treated was shaped by some in order to create a grosteque ‘other’ used to justify the inhuman ways that humans were treated. Thus we can see, for example, British colonial practices forcibly taking ancestral homelands for their resources by displacing, brutalising and damaging cultures (as had been imposed on the indigenous peoples of Britain by a narrow group of people who accumulated wealth and concentrated privilege).

The ‘British Empire’ was majorly involved in a period of history where particularly cultures who had developed the naval capability, were starting to systematically seize land and riches as they perceived it as their right through the stories they told themselves – the ‘political myths’; i.e. the stories which served as charters for action.

Complexity in History; Silences and Power

In order to properly deal with the complexity which the history inevitably involves, it is important to unpack the use (or inference) of categorical perspectives which can accompany language. The notion that the ‘British Empire’, or any collective noun for example, refers to a homogenous group of people who hold the same values, beliefs and intentions should be significantly unsettled. There is always a risk in using such collective nouns because they can act as essentialising reductions of mixed, tangled, idiosyncratic and changing phenomena.

For example, to suggest that “All men think x” in a historical period of the diminishment of the lives of women is to represent something in a simplistic way. For me, the historiographer Michel-Rolph Trouillot in his book ‘Silencing the Past; Power and the Production of History’ has helped me escape flat and two dimensional representations by describing the intimate dynamics of history as a subject.

This is especially exemplified in his asserting that ‘whenever a fact is created, so is a silence’ and that part of the historians job is to look for and into those silences in order to explore power. Trouillot states an important aspect of how human culture comes to be configured in certain ways which can account for apparent lack of deliberacy at times – “Effective silencing does not require a conspiracy, not even a political consensus. Its roots are structural” (Trouillot, 2015; Page 106). Here is the end of the introduction to his book:

“This book is about history and power. It deals with the many ways in which the production of historical narratives involves the uneven contribution of competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to the means for such production. The forces I will expose are less visible than gunfire, class property, or political crusades. I want to argue that they are no less powerful.

I also want to reject both the naive proposition that we are prisoners of our pasts and the pernicious suggestion that history is whatever we make of it. History is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.”

—Michel-Rolph Trouillot

Click here to download introduction and chapter one

Returning to study through Akalas narrative here and now, I looked significantly into the history of Britain picking into the silences overshadowed by the boombastic nature of the empire narratives so recognisable from national curricula. My interest here is not weighted to those people of privilege who had access to resources and who were to have their thoughts amplified by the printing press and establishment society; no, I am interested to know more of the thoughts of those who were not given platforms in order to represent the world as they knew it.

In part this comes of the peoples of the working class which I define as anyone who has no choice but to accept what work they are issued (for more click here). Rather than being hyper focused on the owners of industry, the big historical names fanfared for their apparent achievements, the dynasties of people born into wealth and agency, I am interested in the history of the people who worked in the mills and factories, the everyday person on the Clapham omnibus and the communities of people who were not commonly commemorated in oil paintings.

Jonathan Rose in the introduction to his book ‘The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes’ he prompts: “But what record do we have of ‘common readers,’ such as freedmen after the American Civil War, or immigrants in Australia, or the British working classes?” (page 1). Whilst there are not nearly as many sources for historians to understand histories from different vantage points, we find ourselves in a time where what sources have survived are becoming more available in the digital age.

Deconstructing ‘the British Empire‘ has been fruitful in revealing different narratives which have bearing on the histories of racism being explored here. My introduction to important parts of Working Class history came through via the scholar Peter Shukie who lives and works in Blackburn. Whilst visiting he told me of the history of mill workers of Blackburn and Lancashire being thanked by Abraham Lincoln for their support of the abolition of the trade in enslaved peoples at the time of the American Civil War.

Lancashire was heavily involved in the textiles industry, and the connections between Liverpool and Manchester (aka ‘Cottonopolis’) as major centres of industry in the world also meant that these places were profoundly caught up in the enslavement trade. It had been commonly known that the British establishment had concerted a project of colonialism where much of its wealth and power came via inhumane routes that are coming into proper scrutiny.

The history of the American Civil war becomes a focus in Lancashire history around the ‘Cotton Famine’ where much industry was invested in plantations and farms that profited from the enslavement of African peoples and their horrendous treatment. The movement for abolition of such practices was diffuse and widespread, and this included the subjugated people who worked the cotton mills in Lancashire area. When the industry owners experienced economic shocks to their business, although a vast number of workers were put into frank poverty, there is evidence of their direct support to stop the exploitation of Black peoples through supporting abolition.

Here is an excerpt from Stanley Broadbridges history of ‘The Lancashire Cotton Famine 1861-65’ in the book ‘The Luddites, and other essays’ (Michael Katanka Books Ltd). It includes a quote from the scholar Karl Marx who, with others, made extensive studies of the social and economic conditions which the working classes were exposed to:

According to Ian Harvey in his research: “…in the year 1862, a then-controversial decision taken by Lancashire mill workers changed the dynamics of this booming British industry with long-lasting and historic consequences. These workers refused to use the raw cotton picked by the slaves in the Southern states of America to be processed in their looms. This decision triggered mixed response from various sections of British society: the economy suffered, unemployment rose, violence spread, but the Lancashire mill workers’ righteousness was upheld.

After the Lancashire workers stopped dealing with American cotton, many followed suit and the once booming cotton industry slowed considerably. Within a period of only 12 months, Lancashire started feeling the bite of the ban. Lancashire alone imported more than 1.3 billion pounds of raw cotton, all of it grown by the Southern plantation owners and picked by slaves kept in horrendous and inhumane conditions. The embargo meant that countless looms from across Lancashire had to be shut and left to rust while hundreds of workers were left without work.

Liverpool was made wealthy over the cotton imported from the America; it was a then-famous notion that more Confederate flags were on the shores of Liverpool than in Virginia. A number of papers started writing articles about the loss British economy had to endure due to the ban. However, in an 1862 meeting at Manchester Free Trade Hall, workers vowed to keep the embargo in order to support the United States in its mission to eradicate slavery throughout the North and the South. The result of this decision by the workers was multi-faceted, ranging from hunger and destitution to the historic role and support to abolish slavery. A number of protests up and down the North of England agitating to lift the ban turned violent and soldiers had to intervene to restore order.”

[Harvey, I., (2016), Role of British Workers in abolishing the slavery and winning the American Civil War, The Vintage News, Taken from internet 6.9 24: https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/06/06/role-british-workers-abolishing-slavery-winning-american-civil-war/]

From a Revealing Histories (http://www.revealinghistories.org.uk/tpl/uploads/Education-card-4.2.pdf) learning resource shows us the food aid which was sent to the working people of north England who had boycotted use of Southern cotton harvested by enslaved people. Below is also an image of one of the ‘cotton famine’ flour barrels sent to the starving people of Lancashire by Abraham Lincoln on the ship George Griswold:

Historiography and Investigating Sources

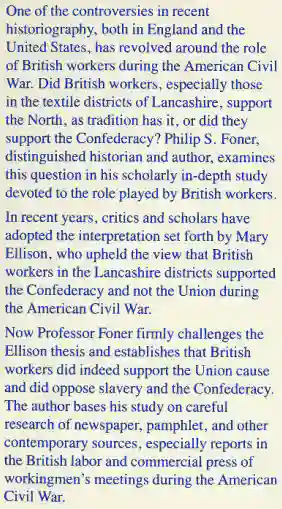

Marika Sherwood in her book ‘After Abolition; Britain and the Slave Trade Since 1807’ suggests that this piece of history is “a myth, born of propaganda [which] survived because, like all myths that endure, it told people what they wanted to believe”. In the excerpt from her text below you can see that a ‘fact’ Sherwood leans on is the equivocal nature of the support coming from the north of England stating Rochdale was the only place to publicly and unanimously support the North in the Amercian Civil War. We also see a more complete quotation from Karl Marx’ article in the New York Tribune, which you can read in full by clicking here: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1861/10/14.htm

[Sherwood, M. (2007). After abolition : Britain and the slave trade since 1807. I.B. Tauris, Page 56.]

To analyse the narrative a first step is to turn to the references which Sherwood cites:

To explain my process, I have managed to get copies of the four references in order to scrutinize the narrative Sherwood has produced. Here we will explore and compare the sources before going on to pick up on some other key historical sources which offer information about the notion working class peoples in north England were actively supporting the abolition of slavery – or whether, as Sherwood has suggested, it is a myth and propaganda.

The first historical source Sherwood draws on to make her point is David Hollett’s ‘The Alabama Affair; The British Shipyards Conspiracy in the American Civil War’. The use of ‘Ibid’ is a Latin abbreviation for ‘in the same place’. As you can see in the reference list above Sherwood cites the evidence from pp. 248 – 52, but on inspecting the book it is only 153 pages long – as you can see in the scan below:

The natural thing to do was to search the book between pages 48 and 52 which seems to yield the relevant historical context for our investigation:

As you can read on page 50 there is both an acknowledgment of the British ruling class expressing allegance to the Confederacy through The Times newspaper, but Hollett’s narrative clearly highlights the working class support for the blockade of cotton grown through exploitation and slavery:

“The Times, organ of the British ruling class and totally sympathetic to the Confederacy, characterised the Emancipation Proclamation as a very sad document. The rest of the Conservative press made similar observations, but the working men of Manchester, many of them victims of the Union blockade of Southern cotton, spoke with a different voice. On 31 December they met in the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, and sent President Lincoln an address of total support. It concluded with these words: “It is a mighty task, indeed, to reorganise the industry not only of four million of the coloured race, but of five millions of whites. Nevertheless, the vast progress you have made in the short space of twenty months fills us with hope that every stain on your freedom will shortly be removed, and that the erasure of that foul blot upon civilisation and Christianity – chattel slavery – during your Presidency will cause the name of Abraham Lincoln to be honoured and revered by posterity…”

Any historian would interpret this citation in order to illustrate that the active objection against slavery by the working people of the north of England was a myth is demonstrating some other ideology at play. It is obvious that the first of the four references undermines Sherwood’s thesis is a plainly stated way.

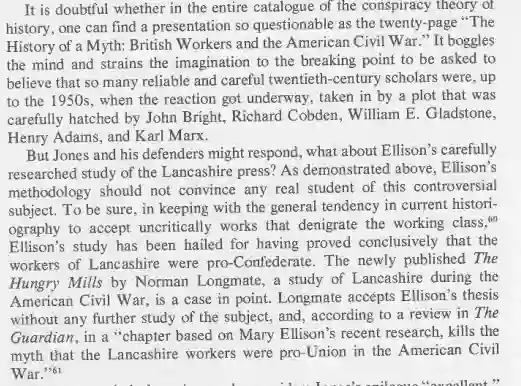

Next I am going to deal with Mary Ellison’s 1972 book ‘Support for Secession; Lancashire and the American Civil War’; the second of Sherwood’s citations to produce support for her argument that British workers supported their unpaid enslaved counterparts in the cotton industry of the USA “is a myth, ‘born of propaganda which survived because, like all myths that endure, it told people what they wanted to believe’.

This reference is actually an interesting portmanteau of writers, and the argument about the myth of working class support for abolition seems largely to have been provided not by the main named author, but more a shadow figure who provided the epilogue to the text written by Mary Ellison, one Mr Peter d’A Jones:

[Ellison, Mary (1972), ‘Support for Secession; Lancashire and the American Civil War’, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, Page 197]

Click here to download Epilogue

Getting a sense of the people who are writing is an important piece of the puzzle. The who, what, where, and when associated with a study helps layer up a picture of the work they are doing, the colleagues they are collaborating with and some of the worldviews they might personally hold. So investigating who Peter d’A Jones is and why he had written the epilogue to her book was my next step in investigating.

From his obituary below, it turns out that Peter d’A Jones was a professor of History at University of Illinois Chicago who published – among other books – ‘The Consumer Society: A History of American Capitalism (1963)’ and ‘The Robber Barrens Revisited’. In the 1970s Jones traveled the world giving lectures for the US State Department corresponding to the offices of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter as presidents. We know that Milton Friedman was a key advisor to Nixon, and when he was impeached, to Gerald Ford; this was followed by Carter carrying Friedman’s policies further. The views of Jones seem to be the ‘free market’ oriented type made famous by the Chicago School of Economics well known for its historical crusade against ‘big government’.

Chicago Tribune, Taken from Internet 8.9.24: www.chicagotribune.com/obituaries/peter-dalroy-jones-vernon-hills-il/

Digging into the details of the lives and careers of authors can help us get some sense about the intentions, motives and agendas which are acting below the surface of texts they have produced. The involvement of Jones in the US State Department in a period where the country was being advised by Milton Friedman whose economic ideas included opposing unions and labour movements, might suggest that his involvement in ending Ellison’s book was specifically connected with his agenda of Political Economy.

It has to be considered that the intentions of Jones was to further Neoliberal policy by undermining the history of the working class movements of activism via reframing it as a “myth of the noble worker”. The reader trying to deepen their sense of history must be able to look at original sources used to construct narratives and ask critically reflective questions; you can read both the preface and the first chapter of Ellison’s work below, as well as the final chapter in the book provided by Jones in order to assess the notions I as a writer have put down:

Click here to download preface and chapter one by Ellison

Click here to download final chapter by Jones

We can see that the book was published via the University of Chicago Press in 1972, a time when the Chicago School of Economics and the agenda of Neoliberal economics had displaced teaching of other perspectives in political economy. The following excerpt references ‘In the fullness of time; the memoirs of Paul H. Douglas’ who was a long standing teacher at the Chicago School of Economics.

From this we can find out that the University of Chicago was founded by John D. Rockefeller in 1892; someone who was publicly identified as a “Robber Barren” – which may account for the development of increasingly aggressive ‘small government’ stances in the institution. This book also helps us get an impression of the atmosphere which had developed in the University of Chicago and its Political Economy policies/teaching creating the setting in which Ellison/Jones’ work was to be later published:

[Douglas, Paul Howard, (1972), In the fullness of time; the memoirs of Paul H. Douglas, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. New York, Page 127]

In the preface to Ellison’s book (see below) we find that it is the product of a PhD, the topic of which was suggested by a Henry Pelling who offered in ideas and criticisms in the process of its construction. Acknowledging understandings of the influences on thinkers like Pelling, who seemed to be a guiding hand on Ellison’s work framing labourers in a particular light, is an important step in the analysis of the historical discourse that is produced.

[Ellison, Mary (1972), ‘Support for Secession; Lancashire and the American Civil War’, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, Page xi]

As a Fellow of the British Academy, the following knowledge about him has been drawn from their biography of his life. Henry Pelling was born in Prenton, the Wirral, a metropolitan borough of Merseyside. He was the son of the Liverpool stockbroker – Douglas Langley Pelling – and Maud Mary Mathison, the daughter of the Birkenhead solicitor who was remembered for having given Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, his first brief. He studied Classics at St John’s College in Cambridge where he got guidance from Sir Michael Moissey Postan, Professor of Economic History, about writing a history of the Independent Labour Party (ILP).

Another influence on this thinker was his supervisor was Professor of Political Science and Fellow of Peterhouse, Sir Denis Brogan. Setting himself up as an academic in the field of labour history he described himself as socialist. The British Academy biography makes particular inferences about Pelling’s approach to documenting the history of labour – “Pelling was an ethical, evolutionary socialist and, above all, an empiricist, determined that triumphalist myth-making should yield to exact scholarship”.

It is worth noting that the British Academy is a Royal Charter organisation which gives insights into the ideas and attitudes promoted by the ‘well to do’. Stuart MacIntyre, a former student of Pelling’s wrote an obituary biography which reveals that he was a member of The Reform Club, a private members club in Pall Mall. MacIntyre offers complementary accounts to those found in the British Academy biography describing his approach as “unheroic, skeptical and mildly revisionist”:

…

Pelling’s history is peppered with establishment success only opened up by the more detailed biographies I have found as a researcher. He became a member of the governing body of Queen’s College, Oxford. How might we see the ideas of Pelling influencing Ellison’s work we are examining ? How can we understand the circumstances and means of Pelling as an author of the history of working class peoples when his life seems so distant from the practical and mundane day-to-day constraints of the everyday person ? We know from the British Academy biography that he had been a very successful investor in the stock market by his bank balance when he passed away:

…

All in all, investigating the influences which converge in this text reveals strong ideological constructions from individuals connected into ruling class and Neoliberal establishments who seem problematically situated in relation to working class histories.

The third source which Sherwood draws upon is that of George Chandler’s ‘Liverpool Shipping; A Short History’:

There is only brief mention on page 35 of the abolitionist context: “In particular Liverpool relied largely on the Southern States for cotton to feed the looms of the Manchester cotton operatives. This was one of the reasons why public opinion in Liverpool was on the whole in favour of the South”. This reference does not offer definitive analysis nor categorical conclusion, but more a generalist perspective that ‘on the whole’, the Southern Confederacy was favoured.

Finally in this exercise of analysis we move to the last reference which Sherwood utilises to underpin her thesis of myth and propaganda – that of ‘British Labor and the American Civil War’ by Philip S. Foner. On first inspection of this book what seems enigmatic is Marika Sherwood’s use of this as a reference, and – it seems – its discounting as a source.

In places where there are equivocal perspectives what is good practice is to contrast and discuss the differences in presenting your argument. Foner’s work is a direct refutation of the Ellison thesis, this being stated on the dust jacket summary: “Now Professor Foner firmly challenges the Ellison thesis and establishes that British workers did indeed support the Union cause and did oppose slavery and the Confederacy”.

To aid the reader and in an attempt to illustrate the practices of collecting, comparing and contrasting original sources, I have included a series of excerpts illustrating some key thrusts of Professor Foner’s argument. As well as this there is the opportunity to read the introduction and first chapter in full. Here, the aim is to think carefully about how Marika Sherwood constructed her summation in ‘After Abolition; Britain and the Slave Trade Since 1807’, how the Pelling-Ellison-Jones project of ‘Support for Secession Lancashire and the American Civil War’ lives up to scrutiny, and why Sherwood might discount the other references she engaged with without bringing into light the analytical reasons for doing so.

Page 3

Page 7

Page 11

Page 13

Page 19

Page 20

Page 22

Page 24

[Foner, P. S. (1981). British labor and the American Civil War. Holmes & Meier.]

Click here to download introduction and chapter one

Taken together, I believe that Sherwood’s historical argument would not pass a basic history exam were these references to be used in order to support the narrative she does. On these grounds I suggest it as an example of dishonest scholarship involved in colonial propaganda designed to influence readers of history in a particular way – one which is counterfactual; one which creates artifical silences revealing a palimpsest of undercurrents working to produce particular discourse.

(I enjoy the word palimpsest, it refers to a a manuscript page from which the text has been scraped or washed off in preparation for reuse in the form of another document)

Returning to the historiography of Michel-Rolph Trioullot, this is a good example of the need to research and compare sources in order to discover what is being silenced in a given narrative. Academia can be understood as a search for the truth which involves a commitment to discovery of the unknown, the erased and the forgotten if, as a society, we are not to convene in Orwell’s (1949, pp.43) dystopia: “The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth“. In his book he explores how a dystopian society ‘manages’ history which brings into sharp relief the need for historiography (the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline) and critically reflective thinking:

[Orwell, G. (1949). 1984: A novel. Signet Classics. Page 90]

Below is a reference to Frank Merli’s book ‘Great Britain and the Confederate Navy, 1861-1865’ reflecting a communication from Henry Hotze (‘a Swiss American propagandist for the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War’) to Judah P. Benjamin (‘an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Louisiana, a Cabinet officer of the Confederate States and, after his escape to Britain at the end of the American Civil War, an English barrister’):

[Merli, Frank, (1970), Great Britain and the Confederate Navy, 1861-1865, Bloomington Indiana University Press, Page 22]

The above source seems to again provide accounts suggestive that there was indeed strong feelings for abolition during the time from Lancashire. Further evidence suggests that the specious account of equivocal support given by Ellison/Jones fails to respect major sources as reflecting the desire to champion equity for black peoples in the southern states. The following is an exerpt of the letter produced from the meeting of peoples at Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 31 December 1862 to Abraham Lincoln:

In response here is the text of the letter which Abraham Lincoln sent to the working people of Manchester:

Lincoln’s Letter to the Working-Men of Manchester, England

EXECUTIVE MANSION, WASHINGTON, January 19, 1863.

To the Working-men of Manchester:

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of the address and resolutions which you sent me on the eve of the new year. When I came, on the 4th of March, 1861, through a free and constitutional election to preside in the Government of the United States, the country was found at the verge of civil war. Whatever might have been the cause, or whosesoever the fault, one duty, paramount to all others, was before me, namely, to maintain and preserve at once the Constitution and the integrity of the Federal Republic. A conscientious purpose to perform this duty is the key to all the measures of administration which have been and to all which will hereafter be pursued. Under our frame of government and my official oath, I could not depart from this purpose if I would. It is not always in the power of governments to enlarge or restrict the scope of moral results which follow the policies that they may deem it necessary for the public safety from time to time to adopt.

I have understood well that the duty of self-preservation rests solely with the American people; but I have at the same time been aware that favor or disfavor of foreign nations might have a material influence in enlarging or prolonging the struggle with disloyal men in which the country is engaged. A fair examination of history has served to authorize a belief that the past actions and influences of the United States were generally regarded as having been beneficial toward mankind. I have, therefore, reckoned upon the forbearance of nations. Circumstances to some of which you kindly allude – induce me especially to expect that if justice and good faith should be practised by the United States, they would encounter no hostile influence on the part of Great Britain. It is now a pleasant duty to acknowledge the demonstration you have given of your desire that a spirit of amity and peace toward this country may prevail in the councils of your Queen, who is respected and esteemed in your own country only more than she is by the kindred nation which has its home on this side of the Atlantic.

I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the working-men of Manchester, and in all Europe, are called to endure in this crisis. It has been often and studiously represented that the attempt to overthrow this government, which was built upon the foundation of human rights, and to substitute for it one which should rest exclusively on the basis of human slavery, was likely to obtain the favor of Europe. Through the action of our disloyal citizens, the working- men of Europe have been subjected to severe trials, for the purpose of forcing their sanction to that attempt. Under the circumstances, I cannot but regard your decisive utterances upon the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country. It is indeed an energetic and re-inspiring assurance of the inherent power of truth, and of the ultimate and universal triumph of justice, humanity, and freedom. I do not doubt that the sentiments you have expressed will be sustained by your great nation; and, on the other hand, I have no hesitation in assuring you that they will excite admiration, esteem, and the most reciprocal feelings of friendship among the American people. I hail this interchange of sentiment, therefore, as an augury that whatever else may happen, whatever misfortune may befall your country or my own, the peace and friendship which now exist between the two nations will be, as it shall be my desire to make them, perpetual.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

So why have we just done all this work of reading texts and comparing them ? Because it relates the way which narratives can be used to obfuscate and revise history when there are ideological agendas at work. Black history has been subject to these forces and the only way which erasure, misinformation, silence and ambiguity can be dealt with is a common development of critical faculties and efforts to honesty construct/deconstruct pictures of what has happened.

Implicit Bias

To the point that even for someone like me who I’d like to feel lots of my followers are socially engaged, know about the world when I post pictures I was in Zimbabwe a couple of weeks ago…

…this just gives you an example, when I post pictures of the capital city of Zimbabwe Harare and they’ve got skyscrapers and nice hotels and the Beautiful Jacaranda trees if you’ve ever been to Harare you’ll know this.

People are like ‘wow they’ve got skyscrapers in Africa’ – I don’t know if people think people in Africa still live in mud huts; and then if people believe, as you’re going to see over the next half an hour, if there was ever a time when everyone in Africa lived in mud Huts, but the strength of propaganda even for people of African origin is still with us to that point that we have this thing called Black History Month.”

The stereotypes and ideas which are transmitted to British people (I speak primarily from my own context) have been loaded with colonial racism to such an extent that it is like wallpaper for many – so ubiquitous that it is unnoticed. Unnoticed it often goes unspoken about and presumed as non-issues by those who it does not affect.

Black History Month is an important movement for world education precisely because in the absence of other representations, the paucity which is left gets assumed as the whole picture. Thus through television appeals, Non-Governmental Organisations, charities and international aid organisations an implicit bias is reinforced and stoked through the negative images projected of the peoples and cultures of African nations, for example.

The picture projected are of starving people in debilitating conditions and circumstances which Dr. Dambisa Moyo (author of Dead Aid) calls the images of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Michael Onyebuchi Eze calls the images projected ‘a pornography of violence and desolation’ which fail to show and build on the powerful generative things which are a part of African nations. Such degenerative narratives of African countries and cultures also fail to discuss structural barriers for such countries adding value to raw materials which are in place from trade agreements and stipulations from organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (organisations that some people have related to me as being ‘economic weapons’).

The patronizing and insulting image produced of the countries where aid organisations go are pernicious and extensive. Many are starting to question the charitable-aid-industrial complex in itself as implicitly biased. As Michael Onyebuchi Eze reminds us, aid does not come for free, it comes with stipulations and strings attached, and it goes (after filling the purses of those who work in the organisations) to particular people in particular positions often with massively detrimental results which Dr. Dambisa Moyo discusses here.

Such implicit bias can run through organisations without those involved particularly being aware of their bias. Dominating voices come to command and control activities recreating colonial behaviours through modern structures:

This continues the propagandistic and condescending colonial legacies we can see exemplified in the likes of Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 poem called ‘The White Man’s Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands‘. Kipling wrote it for Theodore Roosevelt in order to persuade anti-imperialist Americans to back the annexation of the Philippine Islands. Here it is:

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple,

An hundred times made plain.

To seek another’s profit,

And work another’s gain.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

The savage wars of peace—

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch Sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

No tawdry rule of kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper—

The tale of common things.

The ports ye shall not enter,

The roads ye shall not tread,

Go make them with your living,

And mark them with your dead!

Take up the White Man’s burden—

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard—

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light:—

“Why brought ye us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?”

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Ye dare not stoop to less—

Nor call too loud on Freedom

To cloak your weariness;

By all ye cry or whisper,

By all ye leave or do,

The silent, sullen peoples

Shall weigh your Gods and you.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Have done with childish days—

The lightly profferred laurel,

The easy, ungrudged praise.

Comes now, to search your manhood

Through all the thankless years,

Cold-edged with dear-bought wisdom,

The judgment of your peers!

So what pre-occupies minds about places such as Harare in Zimbabwe are not the great histories of the Bantu people who build a city state which was one of the major trade centres on the continent; not the richness and diversity of the sixteen different languages that are spoken by a mix of Shona peoples, Northern Ndebele and other ethnicities, not the cuisine, stories, theatre and histories but something other – something altogether less than what is.

Click to download introduction and first chapter of ‘A History of Zimbabwe’ by Alois S. Mlambo

The history of Black culture is in a process of being reconstituted so that many countries and cultures. Finding out these histories and celebrating them is a central message of many scholars of colour. The world is only to be richer for the correction of aberrations of truth.

This article is a part of a series of works based on the address which Kingslee James McLean Daley (also known professionally as Akala) gave at Oxford University Students Union; the series will use the address in order to introduce various aspects of Black History. This series is the result of researching the presentation from Akala as a contemporary thinker and developing learning artifacts/resources.

The article is annotated with the work of those referenced as primary sources. The original authors should be consulted in their own original words, in their own original contexts in order to note any divergences from the original authors thoughts.