You Too Would Confess: The Psychology of Thought Control by Joost Meerloo – A Digest

This article is a digest of work on ‘high control groups’ and Joost Meerloo’s book published post second world war on Menticide and the psychology of thought control. In order to position myself as to the research, my own interests have been developing through a study of what I call “sublegal violence” after studying the psychology and sociology of dehumanisation.

This work has led me into the terratory of understanding stress and its impacts on cognition and the psychological consonance of the individual in everyday life. To contextualise that a bit, beyond looking at the effects of bad actors, I am asking what the effects are on the mental health of a culture of:

- sleep deprivation and disturbed rest

- prescription and social intoxicants

- constant financial uncertainty and exclusion

- aggressive depersonalised bureaucratic pressures

- substandard and adulterated foodchains

- psychological pollution like the advertising industry

- town planning denuded of social features

- loss of the living environment and other species

- sycophantic, sensationalistic and amoral media systems

- loneliness and isolation

Table of Contents

Introduction

As my work has progressed I have come to realise how impactful psychological violence is. Even in subtle forms violence over time has lasting negative consequences on the capabilities and wellbeing of individuals through its manifestation of chronic stress which damages the mind and body.

The forms of violence which are often normalised and written off in the everyday context as insignificant accumulate as major assaults on the constitution of the individual and must be acknowledged and recognised if culturally we are to deal with the increasing manifestations of mental illness occurring in some industrialised societies such as Britain.

In order to understand the every day I have been turning to thinkers like Joost Meerloo whose text is reproduced in this article verbatim bar the subject headings which I have introduced in order to help the reader navigate the text online – the subject headings are my own and do not appear in the original text.

He practiced as a psychiatrist in the Netherlands until in 1942 he fled to Belgium where he was to escape to England becoming a colonel and chief of the Psychological Department of the Dutch Army-in-Exile in England. What strikes me about his book ‘The Rape of the Mind: The Psychology of Thought Control, Menticide, and Brainwashing’ [from which the later excerpts are taken] is the humanity which is instilled in it.

My interests are not exclusively to understand the harms which humans can – and do – set upon others, but most importantly, they are focused on the qualities of humanity which are so important for non-pathological forms of relationship and society. I have chosen to group the collection of digests and articles under the working category of ‘cult behaviours’ as all of them I see as related to generating pathological cultures large and small – in other words, societies and ways of relating to others which cause illness.

There are endless complexities to work through in this area. Understanding structural violence and how people are behaviourally primed by the context they find themselves in, appreciating that absences of the good/nourishing can often be manifest as harms invisible to observer, and acknowledging that hells are constructed from intensions which on the surface are good all must feature in unpicking the realms of violence that blight human behaviour.

My interests in sublegal violence are especially keen because the legal system(s) as we know them are not suited to deal with these. The realities of domestic abuse are that much of it may not be detected by the naked eye or forensic laboratory. The psychological torture of the individual in a relationship must be investigated and discussed as urgently as the mental harms produced through digital environments from the psychological pollution of advertisements to the deliberative degeneration of worldly experience through poisonous content algorithms.

All this is ‘strong meat’ – meaning, reading about this is emotionally and psychologically demanding; if you study this, you must learn to switch off. It is an area which is to challenge all our comfortable fetishisation of those things sacred to peoples, but, when done in an appropriate way lead us beyond the symbol and fetish back to the heart of why those things are sacred in the first place – what I suggest are the wellsprings of life generally earmarked with pleasure and laughter.

So a word to the reader share to me by a psychologist in this area as they explore these narratives and resources. Take time to slowly work through the materials a little at a time. Figure out how you feel and develop the emotional literacy which is required to parse the terrible histories being explored. Recognise if you are having a stress reaction and ensure you take decisive actions to step back and refocus your attentions on the countervaling positives of humanity. Take time to reflect on seeing those positives in your world around, where you can. Spend time reconnecting to the kind, the generous, those things which are at peace and from which we can rediscover peace through. Occupy your thoughts with something altogether different as a palate cleanser.

I believe the social psychologist and Professor of Psychology Nick Haslam, who has spent considerable energies studying dehumanisation psychology and stereotyping perception produced a study of toilets in order to refocus his mind. By focusing on the dismal for too long and devoting too much energy on understanding the negative, there is a danger that we become overwhelmed through overlearning one part of life over another. Will Martin, a friend who was a journalist, once said to me “The danger is that police see crime everywhere, doctors see disease everywhere and the journalist sees conspiracy everywhere”; he was was, of course, pointing out the dangers of saturation and fixation in powerful contexts.

Again, find ways to bring into balance what you are exposing your mind to. Personally, I find great interest in searching out people who have happy non-conflict based relationships and hearing about them. I spend time paying attention to the small acts of consideration and kindness which are embedded in the world around; it may be seeing someone holding open a door, it may be someone picking up a piece of rubbish and putting it in a bin – find what is rooted in the love of general humanity and life.

What is particularly valuable about the writing of Joost Meerloo is the fact that it was written outside of our current context in the years following the second world war. It gives us as readers the opportunity to work out for ourselves what knowledge and concepts might be transferrable for our context. What follows is a concise reproduction of the text in Joost Meerloo’s book ‘The Rape of the Mind; The Psychology of Thought Control, Menticide and Brainwashing’, but the headings have been introduced to facilitate the reader along with annotating documents to inform the points being made:

Foreword: Menticide

And fear not them which kill the body, but are not able to kill the soul. —Matthew 10:28

This book attempts to depict the strange transformation of the free human mind into an automatically responding machine — a transformation that can be brought about by some of the cultural undercurrents in our present-day society as well as by deliberate experiments in the service of a political ideology.

The Rape Of The Mind

The rape of the mind and stealthy mental coercion are among the oldest crimes of [hu]mankind. They probably began back in prehistoric days when man first discovered that he could exploit human qualities of empathy and understanding in order to exert power over his fellow men. The word “rape” is derived from the Latin word ‘rapere’, to snatch, but is also related to the words to rave and raven. It means to overwhelm and to enrapture, to invade, to usurp, to pillage, and to steal.

Brainwashing And Thought Control

The modern words “brainwashing,” “thought control,” and “menticide” serve to provide a clearer conception of the actual methods by which [the hu]man’s integrity can be violated. When a concept is given its right name, it can be more easily recognized — and it is with this recognition that the opportunity for systematic correction begins.

Dangers To Cultural Interplay

In this book, the reader will find a discussion of some of the imminent dangers that threaten free cultural interplay. It emphasizes the tremendous cultural implications of the subject of enforced mental intrusion. Not only are the artificial techniques of coercion important, but even more so is the unobtrusive intrusion into our feelings and thinking. The danger of the destruction of the spirit may be compared to the threat of total physical destruction through atomic warfare. Indeed, the two are related and intertwined.

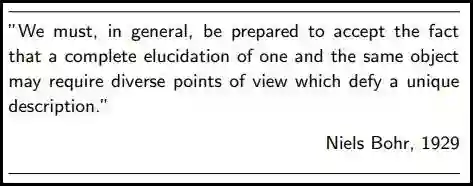

Multi-Faceted Approach

My approach to this subject is based on the belief that it is only by looking at any problem from several angles that we are able to get at its heart. According to Bohr’s principle of complementarity, the rather simple phenomena of physics can be looked at from diverse viewpoints; different and seemingly contrasting concepts are needed to describe physical phenomena. For instance, for the explanation of the behavior of electrons, both the concept of particle and the concept of wave are useful.

The same is true for the even more complicated psychological and social interactions. We cannot look at brainwashing merely from a simple Pavlovian viewpoint. This book tries to do so from the clinical descriptive view and from the Freudian concept of psychology; it tries to look at brainwashing from the standpoint that general mental coercion may belong to every human interaction.

Communication: From Specific To General

Communication of any sort can almost be compared with trying to knock down a row of dolls in a throwing game. The more balls we throw, the greater the probability that we may hit all the dolls. The more approaches we make to any problem, the greater chance we have of finding and grasping its essential core. Such detailed treatment will be impossible without some repetition in the text.

In this book, we shall move from the specific subject of planned and deliberate mental coercion to the more general question of the influences in the modern world that tend to robotize and automatize [hu]man[s]. The last chapters are devoted to the problem of inner backbone, as a first step in the direction of learning to maintain our mental freedom.

The Paradox Of Simplicity

One of the great Dutch authors — Multatuli — wrote a letter to his friend excusing himself because the letter was so long: he had not had time enough to write a shorter one. In this paradox, he expressed part of the problem of all searches for expression and communication. It takes a long time to express an idea in a precise and communicable way. Yet, being short and simple in one’s descriptions is not always appreciated.

Especially modern psychology is loaded with super-learnedness — with the secret intention of leaving the reading public awe-stricken. The man who tries to express himself in simple words, bypassing jargon, risks being called popular and unscientific. Nevertheless, I am aware of the fact that I have been so much steeped in psychological terminology that I cannot completely forego psychological language. The real test of psychological clarity is the way the layman absorbs and understands the ideas communicated. My aim has been to write for the general public, not to popularize but to bring some order to the chaos of our particular epoch.

The Role Of The Author

Every word man speaks is a plagiarism. The task of an author is to absorb, incorporate, and transform the knowledge and emotional currents of his own epoch and to present them in his own personal way, enriched by his own experiences. I am grateful, indeed, to all those whose ideas I have been able to borrow, and especially to all those who inspired me to write down my own thoughts on this controversial subject.

J. A. M. M.

January, 1956

End of Preface

The Techniques Of Individual Submission

The first part of this book is devoted to various techniques used to make man a meek conformist. In addition to actual political occurrences, attention is called to some ideas born in the laboratory and to the drug techniques that facilitate brainwashing. The last chapter deals with the subtle psychological mechanisms of mental submission.

You Too Would Confess

A fantastic thing is happening in our world. Today a man is no longer punished only for the crimes he has in fact committed. Now he may be compelled to confess to crimes that have been conjured up by his judges, who use his confession for political purposes. It is not enough for us to damn as evil those who sit in judgment. We must understand what impels the false admission of guilt; we must take another look at the human mind in all its frailty and vulnerability.

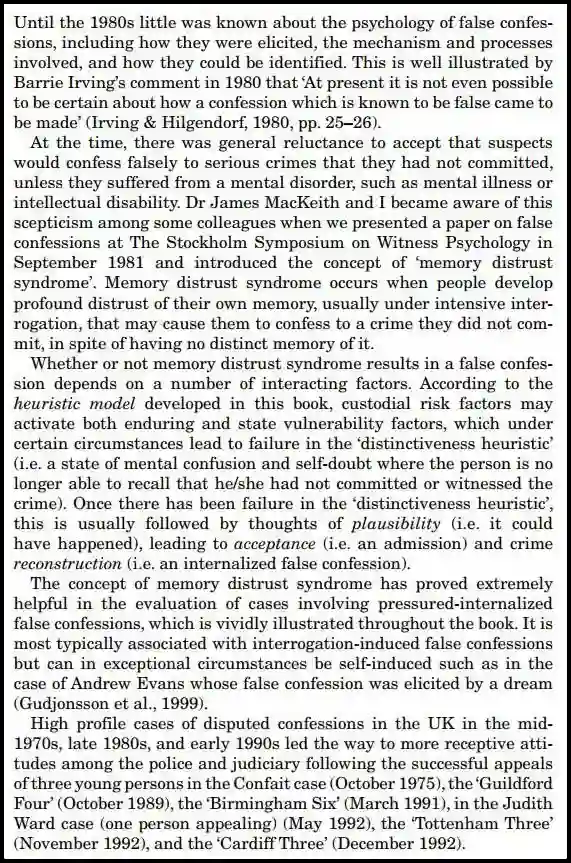

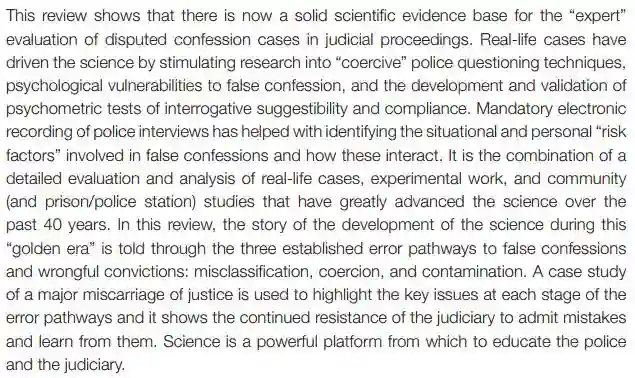

Gudjonsson, G. H. (2018). The psychology of false confessions : forty years of science and practice. Wiley.

Page 438

Page 462

The Enforced Confession

During the Korean War, an officer of the United States Marine Corps, Colonel Frank H. Schwable, was taken prisoner by the Chinese Communists. After months of intense psychological pressure and physical degradation, he signed a well-documented “confession” that the United States was carrying on bacteriological warfare against the enemy. The confession named names, cited missions, and described meetings and strategy conferences. This was a tremendously valuable propaganda tool for the totalitarians. They cabled the news all over the world: “The United States of America is fighting the peace-loving people of China by dropping bombs loaded with disease-spreading bacteria, in violation of international law.”

After his repatriation, Colonel Schwable issued a sworn statement repudiating his confession and describing his long months of imprisonment. Later, he was brought before a military court of inquiry. He testified in his own defense before that court: “I was never convinced in my own mind that we in the First Marine Air Wing had used bug warfare. I knew we hadn’t, but the rest of it was real to me — the conferences, the planes, and how they would go about their missions.”

“The words were mine,” the Colonel continued, “but the thoughts were theirs. That is the hardest thing I have to explain: how a man can sit down and write something he knows is false, and yet, to sense it, to feel it, to make it seem real.”

Click here for wikipedia article

This is the way Dr. Charles W. Mayo, a leading American physician and government representative, explained brainwashing in an official statement before the United Nations: “… the tortures used … although they include many brutal physical injuries, are not like the medieval torture of the rack and the thumb-screw. They are subtler, more prolonged, and intended to be more terrible in their effect. They are calculated to disintegrate the mind of an intelligent victim, to distort his sense of values, to a point where he will not simply cry out ‘I did it!’ but will become a seemingly willing accomplice to the complete disintegration of his integrity and the production of an elaborate fiction.”

The Schwable case is but one example of a defenseless prisoner being compelled to tell a big lie. If we are to survive as free men, we must face up to this problem of politically inspired mental coercion, with all its ramifications.

Historical Context Of Mental Coercion

It is more than twenty years since psychologists first began to suspect that the human mind can easily fall prey to dictatorial powers. In 1933, the German Reichstag building was burned to the ground. The Nazis arrested a Dutchman, Marinus Van der Lubbe, and accused him of the crime. Van der Lubbe was known by Dutch psychiatrists to be mentally unstable.

He had been a patient in a mental institution in Holland. And his weakness and lack of mental balance became apparent to the world when he appeared before the court. Wherever news of the trial reached, men wondered: “Can that foolish little fellow be a heroic revolutionary, a man who is willing to sacrifice his life to an ideal?”

During the court sessions, Van der Lubbe was evasive, dull, and apathetic. Yet the reports of the Dutch psychiatrists described him as a gay, alert, unstable character, a man whose moods changed rapidly, who liked to vagabond around, and who had all kinds of fantasies about changing the world.

On the forty-second day of the trial, Van der Lubbe’s behavior changed dramatically. His apathy disappeared. It became apparent that he had been quite aware of everything that had gone on during the previous sessions. He criticized the slow course of the procedure. He demanded punishment — either by imprisonment or death.

He spoke about his “inner voices.” He insisted that he had his moods in check. Then he fell back into apathy. We now recognize these symptoms as a combination of behavior forms which we can call a ‘confession syndrome‘. In 1933, this type of behavior was unknown to psychiatrists. Unfortunately, it is very familiar today and is frequently met in cases of extreme mental coercion.

Gudjonsson GH (2021) The Science-Based Pathways to Understanding False Confessions and Wrongful Convictions. Front. Psychol. 12:633936. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633936

Van der Lubbe was subsequently convicted and executed. When the trial was over, the world began to realize that he had merely been a scapegoat. The Nazis themselves had burned down the Reichstag building and had staged the crime and the trial so that they could take over Germany. Still later, we realized that Van der Lubbe was the victim of a diabolically clever misuse of medical knowledge and psychological technique, through which he had been transformed into a useful, passive, meek automaton, who replied merely “yes” or “no” to his interrogators during most of the court sessions.

In a few moments, he threatened to jump out of his enforced role. Even at that time, there were rumors that the man had been drugged into submission, though we never became sure of that.

The Moscow Purge Trials

Between 1936 and 1938, the world became more conscious of the very real danger of systematized mental coercion in the field of politics. This was the period of the well-remembered Moscow purge trials. It was almost impossible to believe that dedicated old Bolsheviks, who had given their lives to a revolutionary movement, had suddenly turned into dastardly traitors.

When, one after another, every one of the accused confessed and beat his breast, the general reaction was that this was a great show of deception, intended only as a propaganda move for the non-Communist world. Then it became apparent that a much worse tragedy was being enacted. The men on trial had once been human beings. Now they were being systematically changed into puppets.

Their puppeteers called the tune, manipulating their actions. When, from time to time, news came through showing how hard, rigid revolutionaries could be changed into meek, self-accusing sheep, all over the world the last remnants of the belief in the free community presumably being built in Soviet Russia began to crumble.

Confessions In The Modern World

In recent years, the spectacle of confession to uncommitted crimes has become more and more common. The list ranges from Communist through non-Communist to anti-Communist, and includes men of such different types as the Czech Bolshevik Rudolf Slansky and the Hungarian cardinal, Joseph Mindszenty.

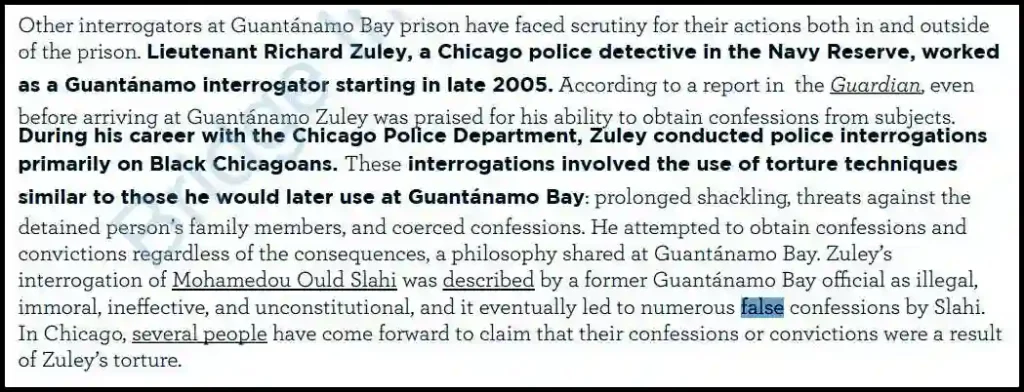

Above: Excerpt taken from Georgetown Iniatiative report on Guantamamo Bay; The Bridge Initiative is a multi-year research project on Islamophobia housed in Georgetown University. The Bridge Initiative aims to disseminate original and accessible research, offers engaging analysis and commentary on contemporary issues, and hosts a wide repository of educational resources to inform the general public about Islamophobia.

Click here for Wikipedia article

Mental Coercion And Enemy Occupation

Those of us who lived in the Nazi-occupied countries during the Second World War learned to understand only too well how people could be forced into false confessions, and into betrayals of those they loved. I myself was born in the Netherlands and lived there until the Nazi occupation forced me to flee. In the early days of the occupation, when we heard the first eyewitness descriptions of what happened during Nazi interrogations of captured resistance workers, we were frightened and alarmed.

The first aim of the Gestapo was to force prisoners under torture to betray their friends and to report new victims for further torture. The Brown Shirts demanded names and more names, not bothering to ascertain whether or not they were given falsely under the stress of terror. I remember very clearly one meeting held by a small group of resisters to discuss the growing fear and insecurity. Everybody at that meeting could expect to be mentioned and picked up by the Gestapo at some time. Should we be able to stand the Nazi treatment, or would we also be forced to become informers? This question was being asked by anti-Nazis in all the occupied countries.

During the second year of the occupation, we realized that it was better not to be in touch with one another. More than two contacts were unsafe. We tried to find medical and psychiatric preventives to harden us against the Nazi torture we expected. As a matter of fact, I myself conducted some experiments to determine whether or not narcotics would harden us against pain. However, the results were paradoxical. Narcotics can create pain insensitivity, but their dulling action at the same time makes people more vulnerable to mental pressure.

Even at that time we knew, as did the Nazis themselves, that it was not the direct physical pain that broke people, but the continuous humiliation and mental torture. One of my patients, who was subjected to such an interrogation, managed to remain silent. He refused to answer a single question, and finally, the Nazis dismissed him. But he never recovered from this terrifying experience. He hardly spoke even when he returned home. He simply sat — bitter, full of indignation — and in a few weeks, he died. It was not his physical wounds that had killed him; it was the combination of fear and wounded pride.

We held many discussions about ways of strengthening our captured underground workers or preventing them from final self-betrayal. Should some of our people be given suicide capsules? That could only be a last resort. Narcotics like morphine give only a temporary anesthesia and relief; moreover, the enemy would certainly find the capsules and take them away.

We had heard about German attempts to give cocaine and amphetamine to their air pilots for use in combat exhaustion, but neither medicament was reliable. These drugs might revive the body by making it less sensitive to pain, but at the same time they dulled the mind. If captured members of the underground were to take them, as experiments had shown, their bodies might not feel the effects of physical torture, but their hazy minds might turn them into easier dupes of the Nazis.

Psychological Preventives

We also tried systematic exercises in mental relaxation and autohypnosis (comparable with Yogi exercises) in order to make the body more insensitive to hunger and pain. If an individual’s attention is fixed on the development of conscious awareness of automatic body functions, such as breathing, the alert functioning of the brain cortex can be reduced, and awareness of pain will diminish. This state of pain insensitivity can sometimes be achieved through auto-hypnotic exercises. But very few of our people were able to bring themselves into such anesthesia.

Finally, we evolved this simple psychological trick: when you can no longer outwit the enemy or resist talking, the best thing to do is to talk too much. This was the idea: keep yourself sullen and act the fool; play the coward and confess more than there is to confess. Later we were able to verify that this method was successful in several cases. Scatterbrained simpletons confused the enemy much more than silent heroes whose stamina was finally undermined in spite of everything.

I had to flee Holland after a policeman warned me that my name had been mentioned in an interrogation. I had twice been questioned by the Nazis on minor matters and without bodily torture. When they later caught up with me in Belgium, probably as the result of a betrayal, I had to undergo a long initial examination in which I was beaten, fortunately not too seriously. The interview had started pleasantly enough. Apparently, the Nazi officer in charge thought he would be able to get information out of me through friendly methods.

Indeed, we even had a discussion (since I am a psychiatrist) about the methods used in interrogation. But when he found that the friendly approach was getting him nowhere, the officer’s mood changed, and he behaved with all the sadistic characteristics we had come to expect from his type. Happily, I managed to escape from Belgium that very night before a more systematic and more torturous investigation could begin.

Psychological Insights From War

Arriving at the London headquarters after an adventurous trip through France and Spain, I became Chief of the Psychological Department of the Netherlands Forces in England. In this official position, I was able to gather data on what was happening to the millions of victims of Nazi terror and torture. Later on, I questioned and treated several escapees from internment and concentration camps.

These people had become real experts in suffering. The variety of human reactions under these infernal circumstances taught us an ugly truth: the spirit of most men can be broken; men can be reduced to the level of animal behavior. Both torturer and victim finally lose all human dignity.

My government gave me the power to investigate a group of traitors, and I also interrogated imprisoned Nazis. When I review all these wartime experiences, all the confusion about courage and cowardice, treason, morale, and mental fortitude, I must confess that my eyes were only really opened after a study of the Nuremberg trials of the Nazi leaders. These trials gave us the real story of the systematic coercive methods used by the Nazis. At about the same time, we began to learn more about the perverted psychological strategy Russia and her satellites were using.

Witchcraft And Torture

The specific techniques used in the modern world to break man’s mind and will and to extort confessions for political propaganda purposes are relatively new and highly refined. Yet enforced confession itself is nothing new. From time immemorial, tyrants and dictators have needed these “voluntary” confessions to justify their own evil deeds.

The knowledge that the human mind can be influenced, tamed, and broken down into servility is far older than the modern dictatorial concept of enforced indoctrination. The primitive shaman used awe-inspiring ritual to bring his victim into such a state of fright hypnosis that he yielded to all suggestions. The native on whom a spell of doom has been cast by the medicine man may become so hypnotized by his own fear that he simply sits down, accepts his fate, and dies.

Throughout history, men have had an intuitive understanding that the mind can be manipulated. Elaborate strategies have been worked out to achieve this end. Ecstasy rituals, frightening masks, loud noises, eerie chants — all have been used to compel the crowd to accept the beliefs of their leaders. Even if an ordinary man at first resists a cruel shaman or medicine man, the hypnotizing ritual gradually breaks his will.

Historical Methods Of Torture

More painful methods are not new either. When we study the old reports of the Inquisition or of the many witch trials, both in Europe and America, we learn a great deal about these methods. The floating test is one example. Those accused of witchcraft were thrown into the river, their feet and hands tied together. If the body did not sink, the victim was immediately pulled out of the water and burned at the stake.

The fact that he [she] did not sink was proof positive of his guilt. If, on the other hand, the accused obeyed the law of gravity and sank to the bottom of the river, the drowned body was ceremoniously removed from the river and proclaimed innocent. Not much choice was left to the victim!

Man has been tremendously inventive in developing means for inflicting suffering on his fellow man. With refined passion, he has devised techniques that provoke the most exquisite pain in the most vulnerable parts of the human body. The rack and the thumbscrew are age-old instruments and have been used not only by primitive judges but also by so-called civilized dictators and tyrants.

The Spiritual Dimension Of Torture

In order better to understand modern mental torture, we must constantly keep in mind the fact that from the earliest days, bodily anguish and the rack were never meant merely to inflict pain on the victim. They may not have expressed their understanding in sophisticated terms, but the medieval judge and hangman were nevertheless aware that there is a peculiar spiritual relationship and mental interplay between the victim and the rest of the community. Much painful torture and hanging had to be done as public demonstrations.

After suffering the most intense pain, the witch would not only confess to shocking sexual debaucheries with the devil, but would herself gradually come to believe the stories she had invented and would die convinced of her guilt. The whole ritual of interrogation and torture finally compelled her to yield to the fantasies of her judges and accusers. In the end, she even yearned for death. She wanted to be burned at the stake in order to exorcise the devil and expiate her sins.

These same judges and hangmen realized, too, that their witch trials were intended not only to torture the witches but even more to torture the bystanders, who, albeit unconsciously, identified themselves with the victims. This is, of course, one of the reasons burnings and hangings were held in public and became the occasion for great pageants. Terror thus became widespread, and many judges spoke euphemistically of the preventive action of such torture. Psychologically, we can see this entire device as a blackmailing of human sympathy and the general tendency to identify with others.

As far back as 1563, the courageous Dutch physician Johannes Wier published his masterwork, ‘De Praestigiis Daemonum’ (On the Delusions About Demons), in which he states that the collective and voluntary self-accusation of older women — through which they exposed themselves to torture and death by their inquisitors — was in itself an act inspired by the devil, a trick of demons, whose aim it was to doom not only the innocent women but also their reckless judges.

Wier was the first medical man to introduce what became the psychiatric concept of delusion and mental blindness. Wherever his book had influence, the persecution of witches ceased, in some countries more than one hundred and fifty years before it was finally brought to an end throughout the civilized world. His work and his insights became one of the main instruments for fighting the witch delusion and physical torture. Wier realized even then that witches were scapegoats for the inner confusion and desperation of their judges and of the Zeitgeist in general.

The Refinement Of The Rack

All knowledge can be used either for good or for evil, and psychology is not immune to this general law. Psychology has delivered up to man new means of torture and intrusion into the mind. We must be more and more aware of what these methods and techniques are if we are successfully to fight them. They can often be more painful and mentally more paralyzing than the rack.

Strong personalities can tolerate physical agony; often it serves to increase stubborn resistance. No matter what the constitution of the victim, physical torture finally leads to a protective loss of consciousness. But to withstand mental torture leading to creeping mental breakdown demands an even stronger personality.

What we call brainwashing (a word derived from the Chinese ‘Hsi-Nao’) is an elaborate ritual of systematic indoctrination, conversion, and self-accusation used to change non-Communists into submissive followers of the party. “Menticide” is a word coined by me and derived from *mens*, the mind, and *caedere*, to kill. Here I followed the etymology used by the United Nations to form the word “genocide,” meaning the systematic destruction of racial groups.

Both words indicate the same perverted refinement of the rack, putting it on what appears to be a more acceptable level. But it is a thousand times worse and a thousand times more useful to the inquisitor.

Understanding Menticide

Menticide is an old crime against the human mind and spirit but systematized anew. It is an organized system of psychological intervention and judicial perversion through which a powerful dictator can imprint his own opportunist thoughts upon the minds of those he plans to use and destroy. The terrorized victims finally find themselves compelled to express complete conformity to the tyrant’s wishes.

Through court procedures, at which the victim mechanically reels off an inner record which has been prepared by his inquisitors during a preceding period, public opinion is lulled and thrown off guard. “A real traitor has been punished,” people think. “The man has confessed!” His confession can be used for propaganda, for the cold war, to instill fear and terror, to accuse the enemy falsely, or to exercise a constant mental pressure upon others.

One important result of this procedure is the great confusion it creates in the mind of every observer, friend or foe. In the end, no one knows how to distinguish truth from falsehood. The totalitarian potentate, in order to break down the minds of men, first needs widespread mental chaos and verbal confusion, because both paralyze his opposition and cause the morale of the enemy to deteriorate — unless his adversaries are aware of the dictator’s real aim. From then on, he can start to build up his system of conformity.

In both the Mindszenty and the Schwable cases, we have documented reports of the techniques of menticide as it has been used to break the minds and wills of courageous men.

The Case Of Cardinal Mindszenty

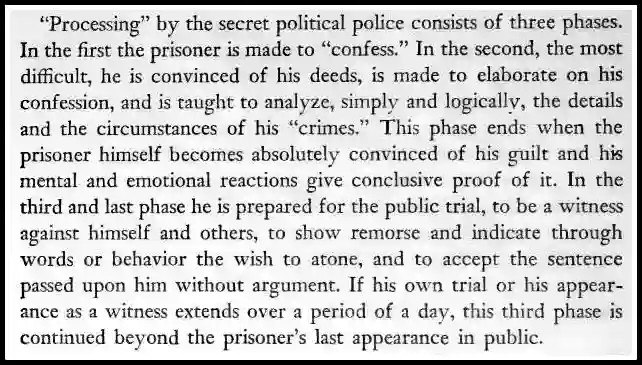

Let us look first at the case of Cardinal Mindszenty, accused of misleading the Hungarian people and collaborating with the enemies, the United States. In his expose on Cardinal Mindszenty’s imprisonment, Stephen K. Swift graphically describes three typical phases in the psychological “processing” of political prisoners. The first phase is directed toward extorting confession.

The victim is bombarded with questions day and night. He is inadequately and irregularly fed. He is allowed almost no rest and remains in the interrogation chamber for hours on end while his inquisitors take turns with him. Hungry, exhausted, his eyes blurred and aching under unshaded lamps, the prisoner becomes little more than a hounded animal.

Swift, Stephen K. (1949), The Cardinal’s Story:The Life and Work of Joseph, Cardinal Mindszenty, Archbishop of Esztergom, Primate of Hungary, Macmillan, Pages 126 – 8

… when the Cardinal had been standing for sixty-six hours [Swift reports], he closed his eyes and remained silent. He did not even reply to questions with denials. The colonel in charge of the shift tapped the Cardinal’s shoulder and asked why he did not respond. The Cardinal answered: “End it all. Kill me! I am ready to die!” He was told that no harm would come to him; that he could end it all simply by answering certain questions.

… By Saturday forenoon he could hardly be recognized. He asked for another drink, and this time it was refused. His feet and legs had swollen to such proportions that they caused him intense pain; he fell down several times.

Inner Terror And Confession

To the horrors the accused victim suffers from without must be added the horrors from within. He is pursued by the unsteadiness of his own mind, which cannot always produce the same answer to a repeated question. As a human being with a conscience, he is pursued by possible hidden guilt feelings, however pious he may have been, that undermine his rational awareness of innocence.

The panic of the “brainwashee” is the total confusion he suffers about all concepts. His evaluations and norms are undermined. He cannot believe in anything objective anymore except in the dictated and indoctrinated logic of those who are more powerful than he. The enemy knows that, far below the surface, human life is built up of inner contradictions. He uses this knowledge to defeat and confuse the brainwashee.

The continual shift of interrogators makes it ever more impossible to believe in consecutive thinking. Hardly has the victim adjusted himself to one inquisitor when he has to change his focus of alertness to another one. Yet, this inner clash of norms and concepts, this inner contradiction of ideologies and beliefs is part of the philosophical sickness of our time!

As a social being, the Cardinal is pursued by the need for good human relationships and companionship. The constantly reiterated suggestion of his guilt urges him toward confession. As a suffering individual, he is blackmailed by an inner need to be left alone and undisturbed, if only for a few minutes. From within and without, he is inexorably driven toward signing the confession prepared by his persecutors.

Why should he resist any longer? There are no visible witnesses to his heroism. He cannot prove his moral courage and rectitude after his death. The core of the strategy of menticide is the taking away of all hope, all anticipation, all belief in a future. It destroys the very elements that keep the mind alive. The victim is utterly alone.

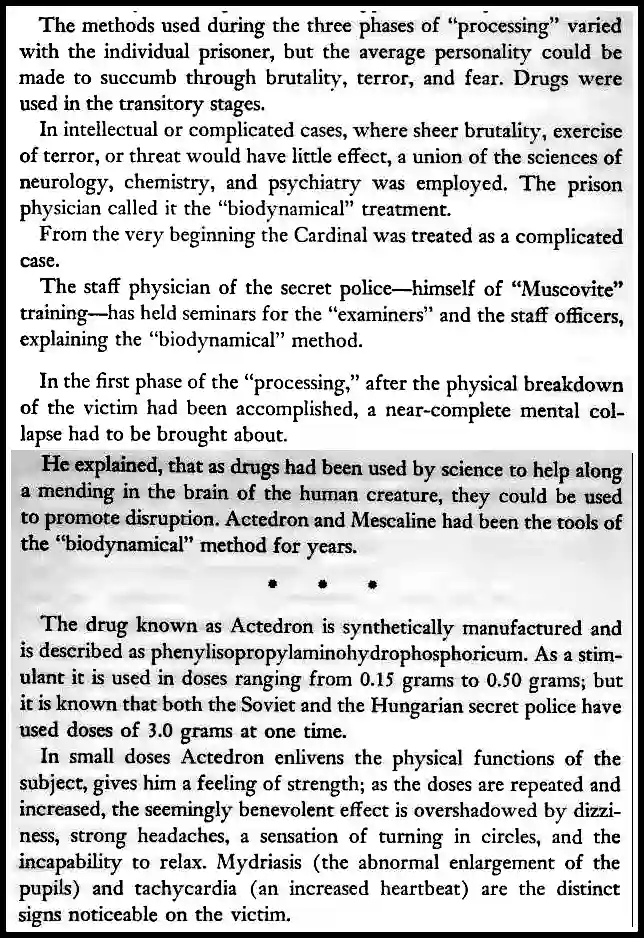

The Role Of Narcotics

If the prisoner’s mind proves too resistant, narcotics are given to confuse it: mescaline, marihuana, morphine, barbiturates, alcohol. If his body collapses before his mind capitulates, he receives stimulants: benzedrine, caffeine, coramine, all of which help to preserve his consciousness until he confesses.

Many of the narcotics and stimulants which ultimately help to induce mental dependency and enforced confusion also can create an amnesia, often a complete forgetting of the torture itself. The torture techniques achieve the desired effect, but the victim forgets what has actually happened during the interrogation.

The clinicians who do therapeutic work with amphetamine derivatives, which when injected into the bloodstream help patients to remember long-forgotten experiences, are familiar with the drug’s ability to bring soothing forgetfulness of the period during which the patient was drugged and questioned.

This continual attack on human conscience and guilt by unconscious self-accusations is brilliantly depicted by Franz Kafka in The Trial. In this novel, the victim never knows of what he is accused, but his inner guilt leads him to conviction. Kafka anticipated the age of blackmailing into confession. His novel was written before the 1930s. The same theme has been treated from a psychological point of view by Theodor Reik in his Confession Compulsion and the Need for Punishment. [See Chapter Three].

Franz Kafka. The Castle; the Trial. Schocken, 1995, page 118

Reik, Theodor. The Compulsion to Confess: On the Psychoanalysis of Crime and Punishment. 1945. Page 180

Conditioning The Victim

Next, the victim is trained to accept his own confession, much as an animal is trained to perform tricks. False admissions are reread, repeated, hammered into his brain. He is forced to reproduce in his memory again and again the fancied offenses, fictitious details which ultimately convince him of his criminality. In the first stage, he is forced into mental submissiveness by others. In the second stage, he has entered a state of autohypnosis, convincing himself of fabricated crimes.

According to Swift: “The questions during the interrogation now dealt with details of the Cardinal’s ‘confession.’ First his own statements were read to him; then statements of other prisoners accused of complicity with him; then elaborations of these statements. Sometimes the Cardinal was morose, sometimes greatly disturbed and excited. But he answered all questions willingly, repeated all sentences — once, twice, or even three times when he was told to do so.”

The Final Phase Of Menticide

In the third and final phase of interrogation and menticide, the accused, now completely conditioned and accepting his own imposed guilt, is trained to bear false witness against himself and others. He doesn’t have to convince himself anymore through autohypnosis; he only speaks “his master’s voice.”

He is prepared for trial, softened completely; he becomes remorseful and willing to be sentenced. He is a baby in the hands of his inquisitors, fed as a baby and soothed by words as a baby. [A more extended survey of the different psychological stages in menticide and brainwashing will be given at the end of Chapter Four.]

Menticide In Korea

Now let us take a look at the Schwable case. In its general outline, it is similar to the Mindszenty story; it differs only in details. As an officer of the United States Marine Corps, fighting with the United Nations in Korea, he is taken prisoner by the enemy. The colonel expects to be protected by international law and by the regulations regarding officer prisoners of war, which have been accepted by all countries. However, it slowly dawns on him that he is being subjected to a kind of treatment very different from what he expected. The enemy looks on him not as a prisoner of war, but as a victim who can be used for propaganda purposes.

He is subjected to slow but constant pressures devised to break him down mentally. Humiliation, rough, inhuman treatment, degradation, intimidation, hunger, exposure to extreme cold — all have been used to crumble his will and to soften him. They need to wangle military secrets out of him and to use him as a tool in their propaganda machine.

He feels completely alone. He is surrounded by filth and vermin. For hours on end, he has to stand up and answer the questions his interrogators hurl at him. He develops arthritic backache and diarrhea. He is not allowed to wash or shave. He doesn’t know what will happen to him next. This treatment goes on for weeks. Then the hours of systematic and repetitious interrogation and oppression increase. He no longer dares to trust his own memory.

Isolation And Intimidation

There are new teams of investigators every day, and each new team points out his increasing errors and mistakes. He cannot sleep anymore. Daily, his interrogators tell him they have plenty of time, and he realizes that in this respect at least they are telling the truth. He begins to doubt whether he can resist their seductive propositions. If he will just unburden himself of his guilt, they tell him, he will be better treated. The inquisitor is treacherously kind and knows exactly what he wants.

He wants the victim captured by the influence of a slowly induced hypnosis. He wants a well-documented confession that the American army used bacteriological warfare and that the captive himself took part in such germ warfare. The inquisitor wants this confession in writing because it will make a convincing impression and will shock the world.

China is plagued by hunger and epidemics; such a confession will explain the high disease rate and exculpate the Chinese government, whose popularity is at a low ebb. So the colonel has to be prepared for a systematic confession, made before an international group of Communist experts. Mentally and physically, he is weakened, and every day, the Communist “truths” are imprinted on his mind.

Hypnotic Influence And Confession

The colonel has in fact become hypnotized; he is now able to reproduce for his jailers bits and pieces of the confession they want from him. It is a well-known scientific fact that the passive memory often remembers facts learned under hypnosis better than those learned in a state of alert consciousness.

He is even able to write some of it down. Eventually, all the little pieces fit, like a jigsaw puzzle, into a complete, well-organized whole; they form part of a document which was in fact prepared beforehand by his captors. This document is placed in the colonel’s hands, and he is even allowed to make some minor changes in the phrasing before he signs it.

The Breakdown Of The Will

By now, the colonel has been completely broken. He has given in. All sense of reality is gone; identification with the enemy is complete. For weeks after signing the confession, he is in a state of depression. His only wish is the wish to sleep, to have rest from it all. A man will often try to hold out beyond the limits of his endurance because he continues to believe that his tormentors have some basic morality, that they will finally realize the enormity of their crimes and will leave him alone.

This is a delusion. The only way to strengthen one’s defenses against an organized attack on the mind and will is to understand better what the enemy is trying to do and to outwit him. Of course, one can vow to hold out until death, but even the relief of death is in the hands of the inquisitor. People can be brought to the threshold of death and then be stimulated into life again so that the torments can be renewed. Attempts at suicide are foreseen and can be forestalled.

In my opinion, hardly anyone can resist such treatment. It all depends on the ego strength of the person and the exhaustive technique of the inquisitor. Each man has his own limit of endurance, but that this limit can nearly always be reached and even surpassed is supported by clinical evidence. Nobody can predict for himself how he will handle a situation when he is called to the test.

The official United States report on brainwashing admits that “virtually all American P.O.W.s collaborated at one time or another in one degree or another, lost their identity as Americans … thousands lost their will to live,” and so forth. The British report gives a statistical survey about the abuse of their P.O.W.s. According to this report, one third of the soldiers absorbed enough indoctrination to be classified as Communist sympathizers.

Sadistic Means Of Torture

The same report describes in a more extended way some of the sadistic means used by the enemy:

- Making a prisoner stand at attention or sit with legs outstretched in complete silence from 4:30 a.m. to 11 p.m. and constantly waking him during the few hours allowed for sleep.

- Keeping prisoners in solitary confinement in boxes about five by three by two feet. A private of the Gloucester Regiment spent more than six months in one of these.

- Withholding liquids for days “to help self-reflection.”

- Binding a prisoner with a rope passed over a beam, one end fixed as a hangman’s noose round his neck and the other end tied to his ankles. He was then told that if he slipped or bent his knees, he would be committing suicide.

- Forcing a prisoner to kneel on jagged rocks and hold a large rock over his head with arms extended. It took a man who had undergone this treatment days to recover the ability to walk.

- At one camp, North Korean jailers pushed a pencil-like piece of wood or metal through a hole in the cell door and made the prisoner hold the inner end in his teeth. Without warning, a sentry would knock the outer end sideways, breaking the man’s teeth or splitting the sides of his mouth. Sometimes the rod was rammed inward against the back of the mouth or down the throat.

- Prisoners were marched barefooted to the frozen Yalu River; water was poured over their feet, and they were kept for hours with their feet frozen to the ice to “reflect” on their “crimes.”

Menticidal Hypnosis

Time, fear, and continual pressure are known to create a menticidal hypnosis. The conscious part of the personality no longer takes part in the automatic confessions. The brainwashee lives in a trance, repeating the record grooved into his mind by somebody else. Fortunately, this, too, is known: as soon as the victim returns to normal circumstances, the panicky and hypnotic spell evaporates, and he again awakens into reality.

This is what happened to Colonel Schwable. True, he confessed to crimes he did not commit, but he repudiated his confession as soon as he was returned to a familiar environment. When, during the military inquiry into the Schwable case, I was called upon to testify as an expert on menticide, I told the court of my deep conviction that nearly anybody subjected to the treatment meted out to Colonel Schwable could be forced to write and sign a similar confession.

“Anyone in this room, for instance?” the colonel’s attorney asked me, looking in turn at each of the officers sitting in judgment on this new and difficult case. And in good conscience, I could reply, firmly: “Anyone in this room.”

The Technique Of Menticide

It is now technically possible to bring the human mind into a condition of enslavement and submission. The Schwable case and the cases of other prisoners of war are tragic examples of this, made even more tragic by our lack of understanding of the limits of heroism. We are just beginning to understand what these limits are, and how they are used, both politically and psychologically, by the totalitarians.

We have long since come to recognize the breast-beating confession and the public recantation as propaganda tricks; now we are beginning to see ever more clearly how the totalitarian uses menticide: deliberately, openly, unashamedly, as part of their official policy, as a means of consolidating and maintaining their power, though, of course, they give a different explanation to the whole procedure — it’s all a confession of real and treacherous crimes.

The Subtle Forces Of Menticide

This brutal totalitarian technique has at least one virtue, however. It is obvious and unmistakable, and we are learning to be on our guard against it, but as we shall see later, there are other subtler forms of mental intervention. They can be just as dangerous as the direct assault, precisely because they are more subtle and hence more difficult to detect.

Often we are not aware of their action at all. They influence the mind so slowly and indirectly that we may not even realize what they have done to us. Like totalitarian menticide, some of these less obvious forms of mental manipulation are political in purpose. Others are not. Even if they differ in intent, they can have the same consequences.

The Impact Of Modern Communications

These subtle menticidal forces operate both within the mind and outside it. They have been strengthened in their effect by the growth in complexity of our civilization. The modern means of mass communication bring the entire world daily into each man’s home; the techniques of propaganda and salesmanship have been refined and systematized; there is scarcely any hiding place from the constant visual and verbal assault on the mind.

The pressures of daily life impel more and more people to seek an easy escape from responsibility and maturity. Indeed, it is difficult to withstand these pressures; to many, the offer of a political panacea is very tempting; to others, the offer of escape through alcohol, drugs, or other artificial pleasures is irresistible.

The Call To Resist

Free men in a free society must learn not only to recognize this stealthy attack on mental integrity and fight it but must also learn what there is inside man’s mind that makes him vulnerable to this attack, what it is that makes him, in many cases, actually long for a way out of the responsibilities that democracy and maturity place on him.

Stephen Hassan’s BITE Model

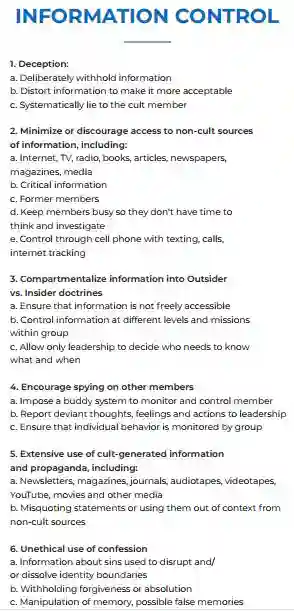

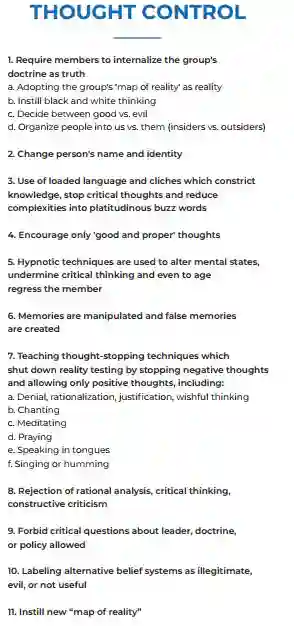

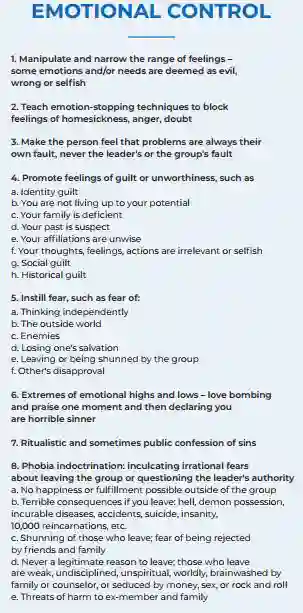

A well known figure in the field of cult behaviour is Stephen Hassan who has developed the BITE Model:

Finally, something which is worth mulling over is that we can be hostage to our own thinking.